Fred Lonidier’s Unrepentant Focus on Workers’ Rights

How did the former union president, Peace Corps volunteer, and Vietnam War resister disrupt the documentary tradition?

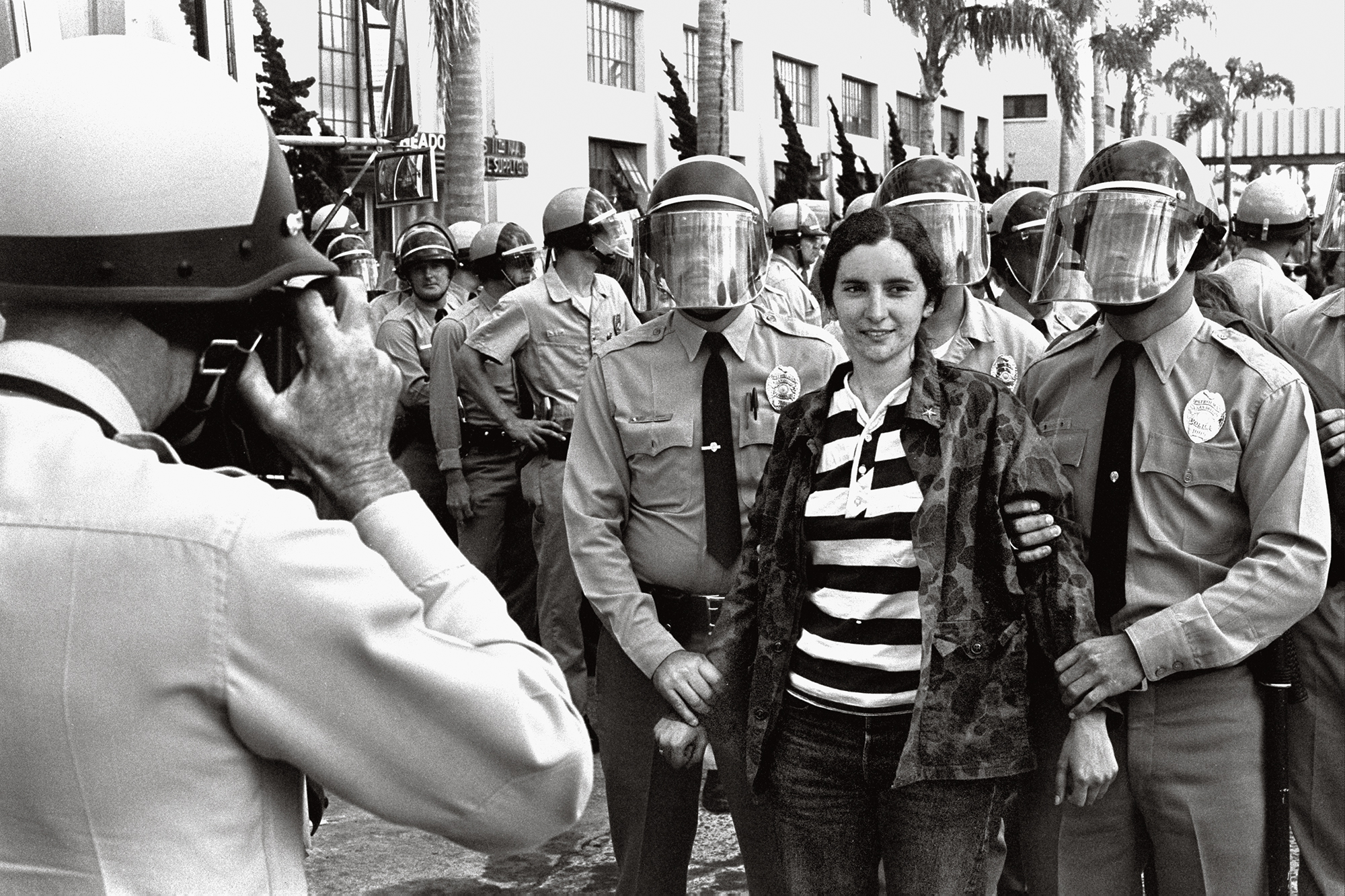

Fred Lonidier, 29 Arrests (detail), 1972

This article originally appeared in Aperture, Spring 2017, “American Destiny.”

When photographer and social activist Fred Lonidier was selected for the 2014 Whitney Biennial, it came as a surprise to some. The last time the seventy-two-year-old professor had shown at the Whitney was his debut in 1977, nearly forty years earlier. But what always distinguished Lonidier’s rigorous documentary work—his unwavering and unrepentant focus on labor and class struggle— was in 2014 suddenly at the forefront of American politics. And many of the most pressing issues of the 2016 presidential election and in recent social activism—including Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and the insurgent Democratic primary campaign of Bernie Sanders—continue to be about labor issues. Numerous problems and discourses affect workers today: achieving income equality, fighting racial discrimination, compensating for outsourced production, accommodating guest workers and immigrant labor, raising the minimum wage, revising global trade policies, and adjusting to the information-economy workforce. Lonidier directs his photography toward these concerns and the workers struggling with them. He has served as president of the local teachers’ union, and his artworks have been commissioned by unions and exhibited in spaces where workers gather. As Lonidier said to me recently, “My work is for, by, and about class struggle through organized labor.”

The forum through which Lonidier engages workers is an expanded documentary practice that combines straightforward photo-text panels with direct action. In the mid-1970s, Lonidier was a key member of a tight circle of photographers and artists at the New Left hotbed of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), which included photographers Allan Sekula, Martha Rosler, and Phel Steinmetz. As part of what was then called the New Documentary movement, these ardently Marxist photographers used theoretical texts and innovative photographic projects to mount a trenchant critical and artistic challenge to postwar humanist photography. Their coherent program of oppositional cultural practices disputed the patronizing sentimentality of much liberal documentary, with its banal construction of victims without agency, arguing that such images were merely a politically disengaged form of artistic self-expression. They challenged traditional fine-art venues, such as museums and galleries, and argued for a more militant and engaged documentary photography, one that would democratize the medium by undercutting its purported objectivity, expose the systemic economic and political systems that shaped photographic “truths,” allow voiceless workers and oppressed minorities to speak for themselves, and yoke their activist cultural criticism to pragmatic political change.

Of these artists, Lonidier was in many ways the most politically engaged and most committed to broad-based critiques of American capitalism. A former Peace Corps volunteer and convicted Vietnam War resister, Lonidier initially studied photography at UCSD as a way to make a living, possibly as a commercial photographer. But his MFA thesis project, a piece titled 29 Arrests (1972), already demonstrated his sly understanding of Conceptualism and how to disrupt the conventions of photographic tradition while foregrounding political activism. The work consists of a series of near identical shots of twenty-nine student antiwar protesters, each being held by cops while a police cameraman takes the person’s portrait. Lonidier adopted a position just behind the official photographer, offering a framing perspective that the mug shots would block out: the legions of seemingly unnecessary police surrounding the nonresistant protesters. Lonidier’s point of view and deadpan style mock the protocols of professional photojournalism. His images almost comically avoid the protest’s dramatic confrontations, showing instead the bureaucratic processing of the accused and the state apparatus in which they are enmeshed.

Lonidier’s project reveals to workers the corporate logic and patterns that lie behind specific incidents and complaints, and encourages solidarity and activist responses.

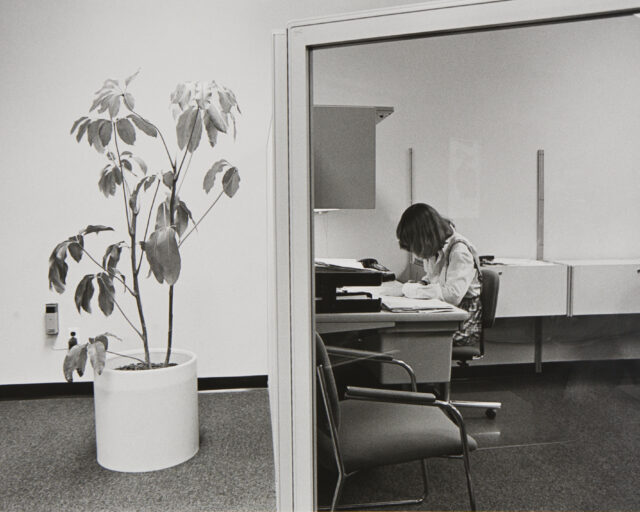

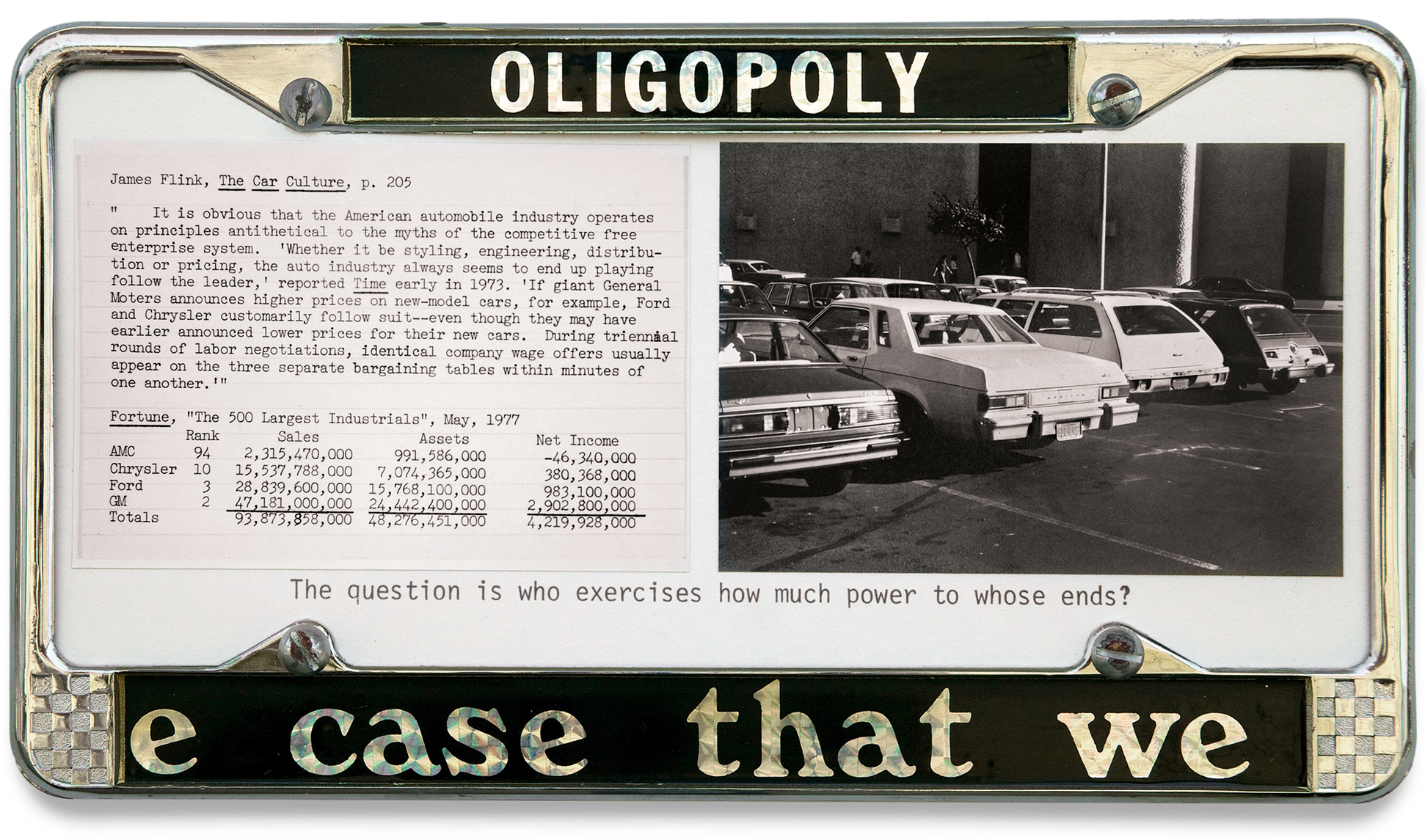

Lonidier’s best-known work, The Health and Safety Game: Fictions Based on Fact (1976–78), is an extended rumination on the brutality of the workplace and the casualties that result. He examines in explicit detail the routine violence of on-the-job injuries, which he portrays as a deliberate calculation sanctioned by the economic “game” of American industry. Across twenty-six panels that look like part of a science fair, Lonidier exposes the impact of corporate decision making, which coldly weighs the negative aspects of workers’ injuries against the steep costs of preventing them. Many of the photo-text panels feature case studies of specific incidents (“Oil Worker’s Burns,” “Office Worker’s Nerves,” “Graduate Film-maker’s Nail”), offering garish photographs of the injuries, as well as step-by-step timelines of the wounds, statements from workers, responses of employers, and testaments to the drawn-out struggles for treatment and compensation. Other text panels explain the various moves available to workers and management within the game. When confronted with health and safety concerns, management can, for example, bust the union, lobby politicians, move to another state, hire undocumented workers, underreport, counter with public relations, or simply violate the standards. Against such tactics, employees have few remedies. Lonidier’s project reveals to workers the corporate logic and patterns that lie behind specific incidents and complaints, and encourages solidarity and activist responses. “I always look for the submerged, missed, or forgotten labor issue,” Lonidier once wrote. “Much of what I have to say is already known and discussed or suspected by workers themselves. It may only be a question of legitimizing or distilling and organizing certain ideas rather than teaching in the one-way sense.”

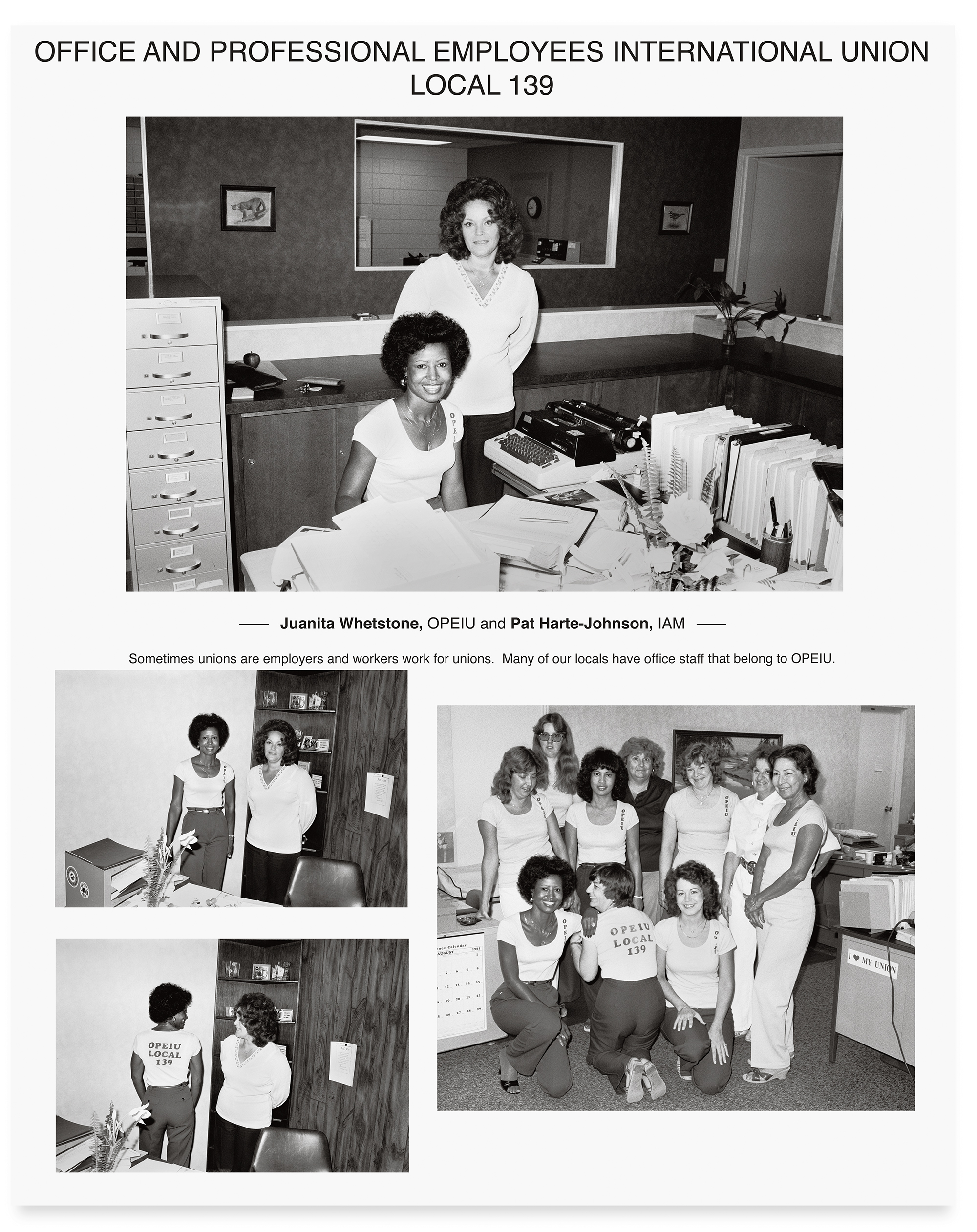

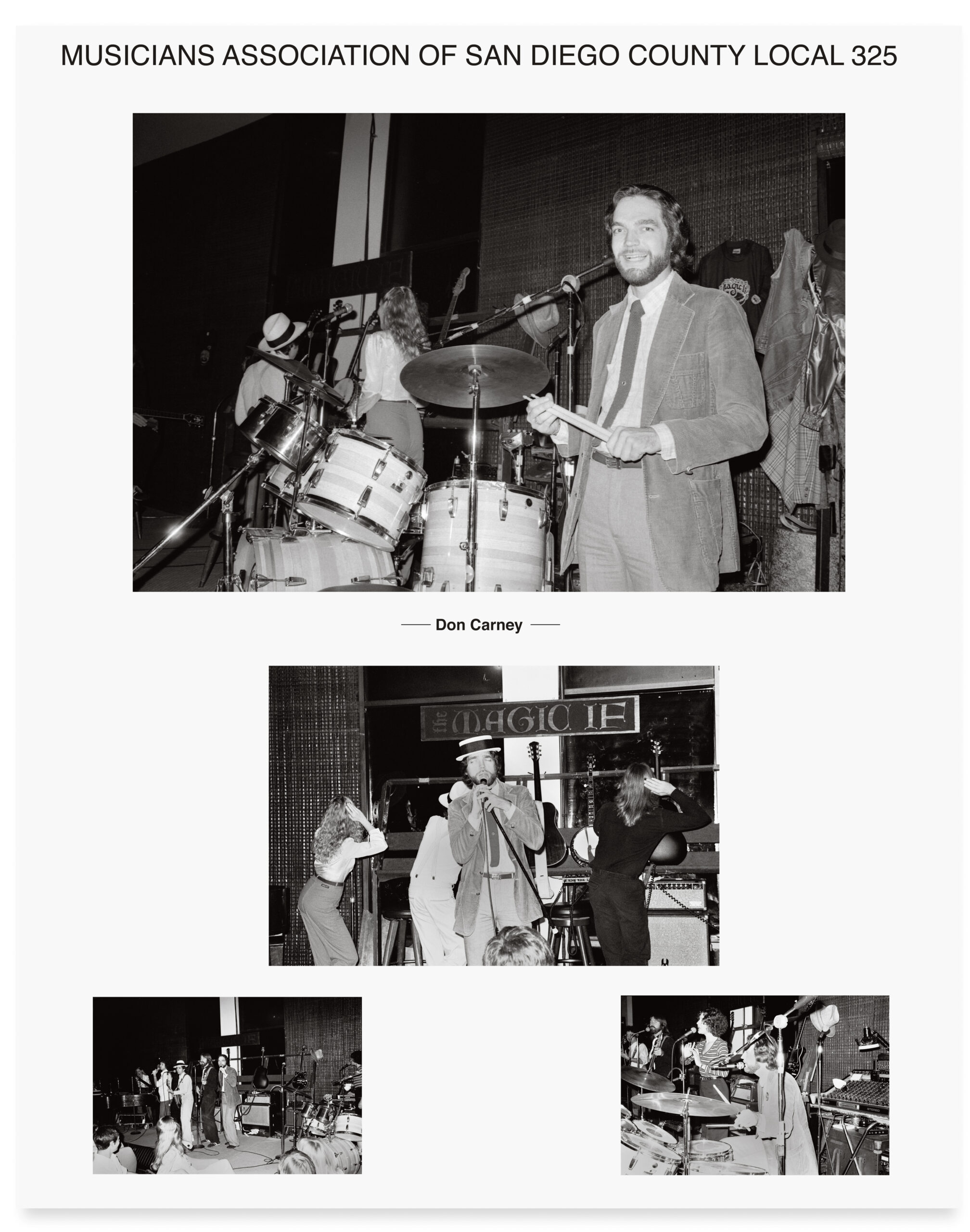

But if The Health and Safety Game is critical of labor relations, other works, like the fifty-six panel I Like Everything Nothing But Union (1983), constitute a wholesale glorification of union workers marching in solidarity. Commissioned by the San Diego-Imperial Counties Labor Council, AFL-CIO and permanently installed in San Diego’s Labor Council Hall, this work was designed specifically to honor the diversity of the union, a view that goes against the univocal stereotype of blue-collar labor. Lonidier’s photographs depict a range of union members at their jobs, from clerical workers to musicians; accompanying text panels quote pithy statements from the laborers that freely offer views on the role of the union, pride in their work, and the ways labor conditions affect their lives, both on and off the job. The dedicated voices captured in this massive and optimistic study counter the conventional view of a silent workforce, grumbling about their lot and unable to represent their own interests. Instead, Lonidier presents a diverse, articulate, and highly opinionated community of workers with clear ideas about how best to achieve constructive political change.

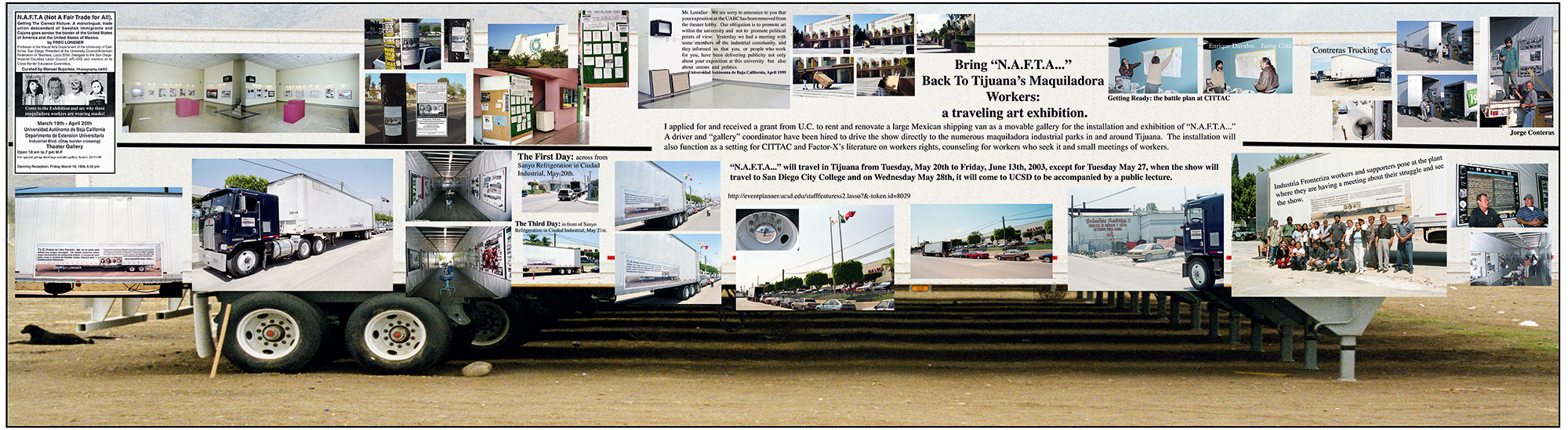

As much as Lonidier’s work reflects a mutating transformation of documentary photographic practice, it also engages with a reawakened social art movement. His long-standing documentary project N.A.F.T.A. (Not a Fair Trade for All), begun in the mid-1990s, suddenly seems timely as it dovetails with widespread political condemnation in the United States of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which eliminated tariffs for trade between Mexico, Canada, and the United States. Even former president Bill Clinton, who signed the treaty in 1993, had insisted on amendments for granting worker and environmental protections and, more recently, has acknowledged some of NAFTA’s negative consequences. As Lonidier shows in the various iterations of his NAFTA documentary project, American companies have redirected production to low-cost light assembly plants, or maquiladoras, just across the Mexican border, thereby paying drastically lower wages and avoiding strict U.S. safety and environmental regulations. Lonidier uses photo-text panels to analyze in plain language and stark images the dire working conditions in the maquiladoras and the recent attempts by some Mexican workers to unionize. When one version of the project was shown at the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California in Tijuana in 1999, administrators closed the exhibition, claiming that Lonidier was an agitator who had distributed leaflets to workers at a nearby factory. Lonidier responded with N.A.F.T.A. #16 A/B: N.A.F.T.A… Returns to Tijuana / T.L.C… Regresa a Tijuana (2005), in which he mounted his photomontages on the outside and interior of a large cargo truck, the kind used to carry immigrant laborers across the border, and toured it to maquiladora zones near Tijuana and colleges in San Diego.

All images courtesy the artist; Maxwell Graham, New York; Michael Benevento, Los Angeles; and Silberkuppe, Berlin

Photographs of the truck highlighted Lonidier’s contribution to the 2014 Whitney Biennial, but the culmination of his participation was undoubtedly the evening teach-in that featured Lonidier lecturing on the connections between art and the working class, and also included a rousing performance by the red-shirted, fist-clenching New York City Labor Chorus singing “Solidarity Forever.” Foregrounding the voices of workers and emphasizing the role of pedagogy, Lonidier symbolically delineated strategies for a new alignment of social-movement art, bringing resonant cultural iconography to the workplace, and inserting labor concerns into the white-cube space of the art museum. “My commitment has long been that the concerns and exhibition of social art be connected in some way to organized efforts towards the same ends,” Lonidier says. “Art that intends to challenge the social world has its best chance in tandem with social/political organizations and their allies.” This ideal remains the incomplete project of an expanded documentary photography.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, Spring 2017, “American Destiny.”