In Iran, Images of a Dystopian Water Crisis

Hashem Shakeri’s pastel-hued, otherworldly photographs depict a landscape on the verge of destruction.

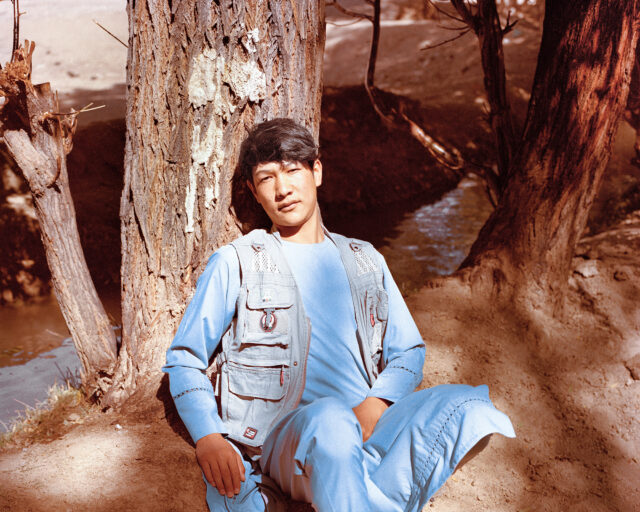

Hashem Shakeri, Hossein, 13, is from Beris, Chaabahar, which is on the sea but lacks secure access to freshwater, 2018

Hashem Shakeri is making a name for himself as one of Iran’s foremost emerging photographers. Trained as an actor and an aspiring filmmaker, Shakeri doesn’t like to be called a photographer; he prefers to be seen as an experimental artist. Whatever label he is given or aspires to, he has captured the attention of the international photographic community with his latest series of photographs about Sistan and Baluchestan, a province in southeastern Iran bordering Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The largest of Iran’s provinces and the birthplace of Rostam, the Persian mythical superhero, Sistan and Baluchestan has a rich cultural history, but the area is also woefully underdeveloped. Thanks to its being on the border of Afghanistan, the province has hosted hundreds of thousands of refugees who escaped the troubles in Afghanistan and have come searching for work in Iran. There is widespread poverty, and major and petty smuggling of people and goods across the porous border is a way of life. This has turned the province into Iran’s “wild east,” where the rule of law is fragile. Shakeri’s recent series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun (2018) focuses on the acute water crisis in the region, which also resonates on a national level.

The water crisis in Sistan and Baluchestan is caused by factors that threaten acute water shortages in all of Iran: a steady decrease in annual rainfall, the rise in population, and shortsighted planning by various governments in water distribution. In Sistan and Baluchestan, the problem points also to a failure in understanding that foreign policy must include environmental issues like water rights. Many in Sistan and Baluchestan believe that Afghanistan’s control of the river Helmand, through the construction of dams and, more recently, irrigation canals, has led to the drying of Hamun Lake, the life source of the Iranian province; the Afghans point to water mismanagement on the Iranian side. Earlier this year I spoke to Shakeri in Tehran about his recording of the drying of Sistan and Baluchestan.

Courtesy the artist

Haleh Anvari: How did you become interested in Sistan and Baluchestan and its environmental problems?

Hashem Shakeri: I have to take you back to when I first became aware of Sistan and Baluchestan Province. About ten years ago I got a call from one of my friends, who told me to hurry to a mutual friend’s house. Her name was Negar. Negar was a childhood friend from my neighborhood; she was a beautiful and gentle girl. I was told that her father had killed her, because she wanted to marry a man and her father didn’t approve. When I got to her house I saw women dressed in a kind of traditional clothing I had not seen before. They were wailing and scratching their faces, mourning in their own traditional way. Their clothes and the women’s behavior made me curious, so I asked where they were from, and I was told that they were Baluchis, from Baluchestan. That’s the first time I heard the name of this province. And something stuck in my head about wanting to know why they were so different.

Six years ago, visual storytelling became important for me, and my priority changed to working on documentary photography to tell the story of different peoples of Iran. I remembered Negar and decided to go see the place for myself. But because of security reasons, Sistan and Baluchestan being on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, I couldn’t go there easily. The place can be unsafe. Border patrol soldiers are regularly kidnapped. The project was too difficult and also too costly.

Then in 2018 I received a scholarship to the Danish School of Media and Journalism. I chose Sistan and Baluchestan as my final project topic. This was the best opportunity for me to cover this topic. I could borrow a medium-format camera from the school, which I couldn’t afford to buy myself. I had a sense that medium format, because of the atmosphere it creates, would be the right camera for this story. I also got the chance to research the subject. This project is my best-planned and best-researched project.

I arrived in the region with an understanding of the place and its situation, because I had the means to research the topic before setting off. I spoke to a number of fixers and used different drivers who facilitated access to a story that is happening very quietly out of sight. As soon as I got there I knew what the title of my project should be: “The Tired and Forgotten Land”—because that is what I was facing. I was looking at a vast emptiness that has a five-thousand-year history and was once known as Iran’s grain store because it was so lush and productive. But in the past eighteen years this place has changed so much, you’d think that all the Persian mythology that tells stories of this green and fertile land must have been lies.

Climate change is happening all around the world, but I believe in Sistan and Baluchestan it is directly affecting the sense of dignity of the people. Here the basic status of humanity is being challenged.

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: When you say humanity’s status is being challenged in Sistan and Baluchestan, is climate change the only factor that is making life difficult for the inhabitants of this region?

Shakeri: In the past eighteen years, climate change has had a direct effect on people’s lives. In 1973, Iran and Afghanistan signed a treaty about the right to the waters of the Helmand River for the people living downstream. The Helmand poured over the border into Iran, filling the Hamun Lake, then turned around again and returned to Afghanistan in a loop.

In 1998 the Afghan government built four irrigation canals to distribute the water of the Helmand River on their side, obstructing it from flowing into Iran, reneging on their 1973 treaty. As a result, Sistan and Baluchestan Province has experienced nearly two decades of drought, which has become acute in the past ten years. Four years ago, the yearly Helmand flood filled the Hamun once again, but it had been dry for so long, the water disappeared into the ground. No doubt mismanagement has added to the crisis. The province is full of half-finished projects.

The majority of the people who live in this province were farmers once, so when the water ran out, it took their livelihood with it. They have turned to smuggling petrol or people across the border. Twenty-five percent of the population has migrated. They move to the nearest place with water. Most of the people from Zabol have migrated to Golestan Province to the north so they can continue as farmers. Some go to Chabahar to the south on the Oman Sea for water, but there is no sweet water there. So they end up being taxi drivers. It’s a case of absolute poverty here. Unemployment leads to addiction and that leads to all sorts of other problems. If I want to record the different ways that lack of water is affecting the lives of people there, I will have to travel to the region several times over three or four years to be able to tell all the stories.

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: I’ve heard from a friend who grew up in Zabol that there were so many fish in the river that she used to catch fish with her hands as a child. That’s how much water they used to have. A section of society lived on fishing alone.

Shakeri: I photographed three young men who were fishing under the Zahak dam, right opposite the governor’s office. The dam is now where the city’s waste is collected. I asked them if they were going to eat the fish from this dirty water; they said no, they will sell it to the poorer families who can’t afford anything better. The boys will buy bread for themselves with the money.

A little further under a bridge near the dam, five addicts were hanging out. I spoke to one of them and photographed him—Hoveyda, a thirty-year-old man who was collecting rubbish. He was living in a hole by the pipes running the drinking water supply of the city very close to the governor’s office. But no one does anything. He said he wanted to go into rehab, but feared that he would be arrested because he doesn’t have a birth certificate. These problems are all visible to the authorities, so quite clearly there is a case of mismanagement here as well.

There was a time that the people of this province lived like kings, through their farming. There is a famous wind called the 120-day wind, which can actually last for 170 days. It blows across the province. Sometimes the speed reaches 120 kilometers per hour. It blows across Lake Hamun. Imagine when there was water in the Hamun—this wind would hit the water and return at speed, working like a natural cooling system. Now, the lake is a dustbowl. When the wind blows, it brings only dust. You sleep at night and in the morning your doorway is covered in a heap of dust. This dust is destroying people’s lives. In 2016 this region was one of the most polluted areas. So it’s not just drought, but pollution too. I went to the region once just for the winds but I kept having to stop working, because my mouth would fill up with dust.

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: What’s the difference in the problems facing this region and other areas of Iran facing loss of water in a dramatic way, like Lake Urmia, or Isfahan’s Zayandeh Rud?

Shakeri: I have visited these other areas too. I think because these two cases are closer to the capital, they have received a lot of publicity. I decided to go to S&B because as a minority people in a marginal geography, their voice is not heard. It’s like they are screaming but no one is hearing them. The place reminded me so much of Waiting for Godot. It’s years that they are just waiting for something to happen, for a miracle to happen. A people who had a magnificent past are sitting waiting for that past to reappear again. But they seem to be completely dispossessed now. Some of the people here don’t even have birth certificates, because they may have moved over from Pakistan. So they live in homes made of date branches.

Anvari: It sounds like you had so many different social issues that you could have zoomed your lens on throughout this project.

Shakeri: I decided to stick to the water shortage as the main theme of my project so as not to get lost and distracted by the various issues. All the other problems are so grave they need to be looked at separately.

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: Let’s have a look at the form of your photographs. You said it was your first time using medium format. One thing that sticks out to me as someone who sees a lot of photos of Iran is the colors that run across the whole series—a dreamy set of pastels that have a dusty look about them. Are these the colors of drought? Because there is a sublime beauty to them. You have managed to inject some romance into this rather dire situation.

Shakeri: I see myself as an experimental artist more than a photographer. Anyone can take photographs, these days. People are taking amazing photos with their phones, but that’s not art. I thought very hard about how I would treat this story. I do this with every project. I’m a documentary photographer, and visual storytelling is what I do. For me visual storytelling is no different from any other filmmaking or any other medium in art. I have to use whatever I need to be able to tell a dramatic story, which I like to imbue with a poetic atmosphere. My world is without time or geography. A no-man’s-place that can occur anywhere. I’m looking for the human soul, so if I work on climate change in the US, I might create a similar atmosphere.

When I got to the location, I encountered a sharp light and most of my photography happened at midday. So I went up by three or four stops as I took the pictures, so I could escape the sharp light. This overexposure made the impression of desolation that I had about this place possible. I was hugely inspired by Roy Andersson, who creates dead and dramatic atmospheres, and Michael Haneke, who changed my life completely, not only in art but in my personal life. I learned from him about the relationships between people and their states of mind, but also how I can photograph between my own imagination and the reality. I love my own subjectivity.

If there is an incident, even if there are no photojournalists around, many people can capture that image—but how many people can turn it into a story? I think about how I take a photograph subjectively, so as to make the story my own. The more personal it is, the more the viewer can connect to the story and the more awareness it creates.

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: Can we say that you have taken the voice of the locals, which you say you hear as a scream, and changed it to a song?

Shakeri: I like that analogy. I like the photos I take to be poetic even if they are about the most bitter and horrific human experiences. Not necessarily beautiful, but what seems aesthetically right to me. Maybe this is my decisive moment, the intuition that I am experiencing at the time. It’s a challenge looking at a disaster and making it beautiful and effective.

Anvari: These photos are certainly not hard on the eyes, considering all the hardship you found surrounding the story. Maybe that’s why they are attracting so much attention, which in turn brings attention to the water and environmental issues that people might turn away from otherwise.

Shakeri: I think sometimes, viewers feel they are having an issue shoved down their throat. With this series, I was surprised that mainly art magazines and even a fashion magazine have asked to publish the images.

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: This makes a lot of sense, specifically about one of your photographs, where a Baluchi man is standing by a rock in the wind. It’s a beautifully evocative photo where the eye is held by the folds of the man’s local outfit. We don’t see any of the horrific issues that you witnessed in this photograph, not the poverty, not the environmental disaster—it looks exactly like a fashion photograph.

Shakeri: Exactly. Medium format’s perspective creates that atmosphere. I tried to work in a minimal way, and the format requires a certain stillness. Plus the fact that I had to be frugal about the use of the medium-format film, because you can’t find it in Iran. So I had to learn to wait for my shot. The photo of the family taking the soil of the dry riverbed for their garden took me twenty hours to get.

Anvari: Apart from the foreign artists you have mentioned, do you see any Iranian photographers’ influences in your work?

Shakeri: Not directly. But no doubt our war photography has had an effect on me, how could it not? People like Abbas Attar, Alfred Yaghoubzadeh, Mohammad Farnood, Kaveh Kazemi, and their war photography have definitely made an impression on my subconscious, because I saw their photos during the war years as a youngster. But I have tried to take it up a level. If you look at the Magnum archive, which I have scoured studiously, up until ten years ago, all the photographers were feeding from the same visual subconscious; you can’t tell their photographs apart. Classic black-and-white. But then it changes by bringing in new photographers who are experimenting with art.

I reach out to other arts. I am a professional actor and have tried to find a common ground between photography and theater, because photography wasn’t going to be enough.

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: You’ve received a lot of attention outside Iran with this series. What’s been the reaction to this work inside?

Shakeri: I offered the photos free of charge to some Iranian publications but none of them would take them. Even though I am highlighting how Afghanistan is infringing on Iranian rights to Helmand water. This made me very sad. After all, these photos should be seen in Iran by Iranians first and foremost, on huge billboards, so they know what’s going on in Sistan and Baluchestan.