Subversive Novelist Seeks Her Muse in Pictures

In San Francisco, Hanya Yanagihara stages an exhibition about loneliness and beauty.

Richard Misrach, Untitled (Hawaii XV), 1978 © the artist and courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

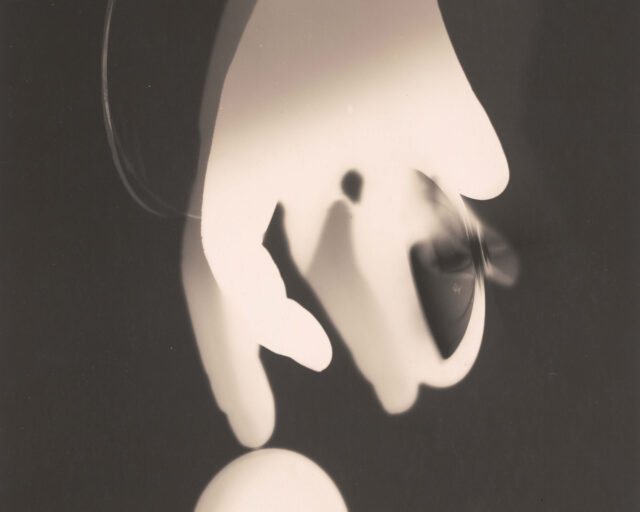

Hanya Yanagihara’s novel A Little Life is seemingly everywhere, from bookstore displays to a shelf in my therapist’s office. On the cover is a powerful, closely cropped photograph of a man in the throes of petit mort. His eyes are tensely shut, his hand gracefully splayed along his cheek in a classical pose fit for a Greco-Roman sculpture. I’d seen this picture in Fraenkel Gallery’s 2014 Peter Hujar exhibition, Love & Lust, which positioned male nudes and erotic works in the context of gay history and bohemian New York. Hujar’s Orgasmic Man (1969) makes a particularly enthralling icon for A Little Life, leading one to imagine this unnamed man is the emotional focus of a feverishly addictive book. Yet the choice of a man in ecstasy is ironic; the book itself reveals a plot focused on pain, addiction, and abuse. (The Guardian’s laudatory take is headlined “relentless suffering.”)

Alec Soth, Riverview Motel, 2005 © the artist and courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Yanagihara has been visiting Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco for seventeen years, so the appearance of a summer group show curated by the author isn’t entirely out of left field. Her history with the gallery suggests she is clearly aware of Fraenkel’s large stable of photographers. Yet the resulting exhibition, How I Learned to See: An (Ongoing) Education in Pictures, doesn’t offer many surprises—most of the photographs by Diane Arbus, Robert Adams, Katy Grannan, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Nicholas Nixon, and others, including Hujar, have been shown here before—but Yanagihara’s exhibition has a literary bent that gives the works a minor new spin.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Lucybelle Crater and bakerly, brotherly friend, Lucybelle Crater, 1970–72 © The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard and courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

How I Learned to See takes the dialogue between image and text in the opposite direction as the cover of A Little Life by using words as an entry to the pictures. The show is installed in thematic chapters named after the kind of big themes that fuel great novels: Loneliness, Love, Aging, Solitude, Beauty, and Discovery. Each begins with its own text panel, written by the curator. The first reveals how Yanagihara is casting a wide novelistic net with her headings, describing them as “the things that define any life, and therefore the things that define all of us, a chronicling of the perpetual mystery of being alive.” It’s a serviceable, if broad, premise, though not quite as free as one would expect from an outsider set loose in a trove of major works.

Robert Adams, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1968 © the artist and courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

In many ways, the result feels like the works are selected simply to illustrate themes. The “Loneliness” chapter, for example, features Robert Adams’s Colorado Springs, Colorado (1968), a classic, Edward Hopper-esque black-and-white image of a suburban ranch house façade with a woman’s silhouette framed in a window. It’s a great picture that declares loneliness straightforwardly. So does Alec Soth’s Riverview Motel (2005), a color image that presents the noir narrative setting of fleabag lodgings where some solitary character is holed up on the lam, perhaps the worn, gender fluid character in Grannan’s blaring sunlit Anonymous, Los Angeles (2008).

Katy Grannan, Anonymous, Los Angeles, 2008 © the artist and courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Portraits of same-sex couples populate the “Love” section. Pictures by Nan Goldin and Arbus, and a Meatyard photo of his wife “in a hideous hag’s mask.” Yanagihara’s wall text points to illegal, ambiguous, tortured, damaged, artistic, parental, and defiant versions of love. These images are narrative provoking; they invite us to imagine a particular scenario for each. As such, the exhibition sometimes feels like a collection of writer’s prompts.

Peter Hujar, Joseph Raffael at the Botanical Gardens, 1956 © The Estate of Peter Hujar and courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

The best moments are when Yanagihara uses the exhibition as a platform to ask questions. In the “Beauty” section, she ponders what that concept means to the camera: “Is it a lovely face? Or something else: a child captured in a moment of self-generated ecstasy; a wooden house piebald with shadows; a second of abandon we shouldn’t be witness to . . . but are?” Among the few surprises are two Hujar photographs from the 1950s. One is Joseph Raffael at the Botanical Gardens (1956), a portrait of a handsome artist sitting amidst foliage: a young man captured in a moment of thrilling contemplation. Yanagihara understands that seeing such potent images are as rooted in time as reading a novel. “The fact that what makes something beautiful is, after all, its temporality,” she writes. “Blink, turn your head, and it’s gone.”