Hervé Guibert’s Passionately Restrained Photographs

Wildly prolific, the late French writer was driven, compulsive, and rarely satisfied—and his own little-known photographs remain as elusive as ever.

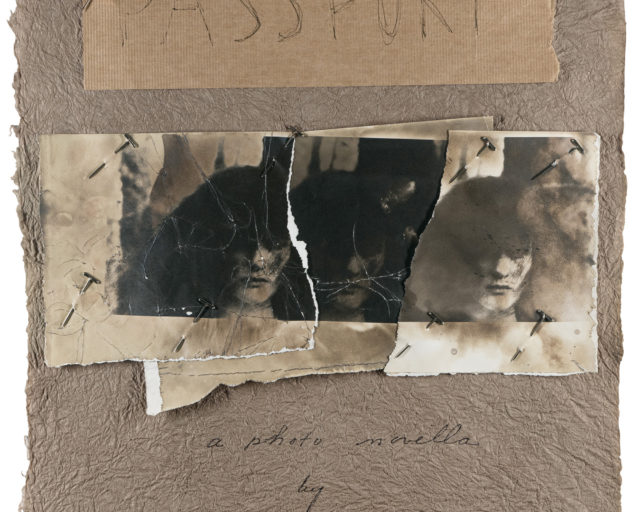

Hervé Guibert, Autoportrait et pantin (Self-portrait and puppet), 1981

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 217, “Lit,” winter 2014.

I shall always refuse to be a photographer: this attraction frightens me, it seems to me that it can quickly turn to madness, because everything is photographable, everything is interesting to photograph, and out of one day of one’s life one could cut out thousands of instants, thousands of little surfaces, and if one begins why stop? — Hervé Guibert, The Mausoleum of Lovers, Journals 1976–1991

When Hervé Guibert died in 1991, he had just turned thirty-six. A year before, the writer, journalist, and photographer had opened his autobiographical novel, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, with the declaration that he had AIDS, but went on to insist that he “would become, by an extraordinary stroke of luck, one of the first people on earth to survive this deadly malady.” When the book caused a sensation (magnified by the fact that one of its characters was a thinly disguised Michel Foucault, whose HIV-positive status contributed to his death in 1984), Guibert became the strikingly handsome, articulate, and very public face of AIDS in France. He didn’t avoid the spotlight, but it made him famous in a way he never wanted to be, and the attention exhausted him even before the disease left him frail and nearly blind. that extraordinary stroke of luck eluded him. Two weeks before he succumbed, he tried to commit suicide with an overdose of pills but failed.

Wildly prolific, Guibert was driven, compulsive, and rarely satisfied. He wrote twenty-three other books, nearly all of them in the ten years before his death (only a handful have been translated into English). In The Mausoleum of Lovers, a collection of journal entries published posthumously in 2011 and just translated, he often sounds melancholic, if not desperate, but then much of it was written as an open letter to an inconstant lover who was allowed to read the journals as they were written. Melodramatic moments—furious, passionate, delusional—alternate with cooler observations, often about photography, which was, along with writing, a highly personal form of expression for Guibert. “The photo that someone other than I could take, that isn’t bound to the particular relation I have to this or that, I don’t want to take it,” he writes.

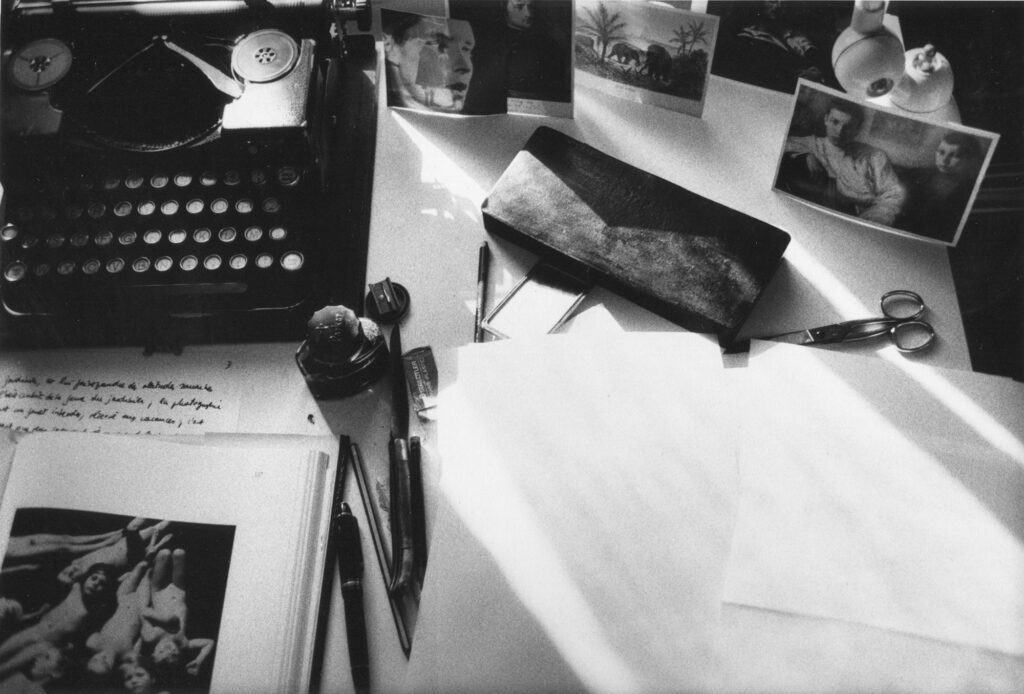

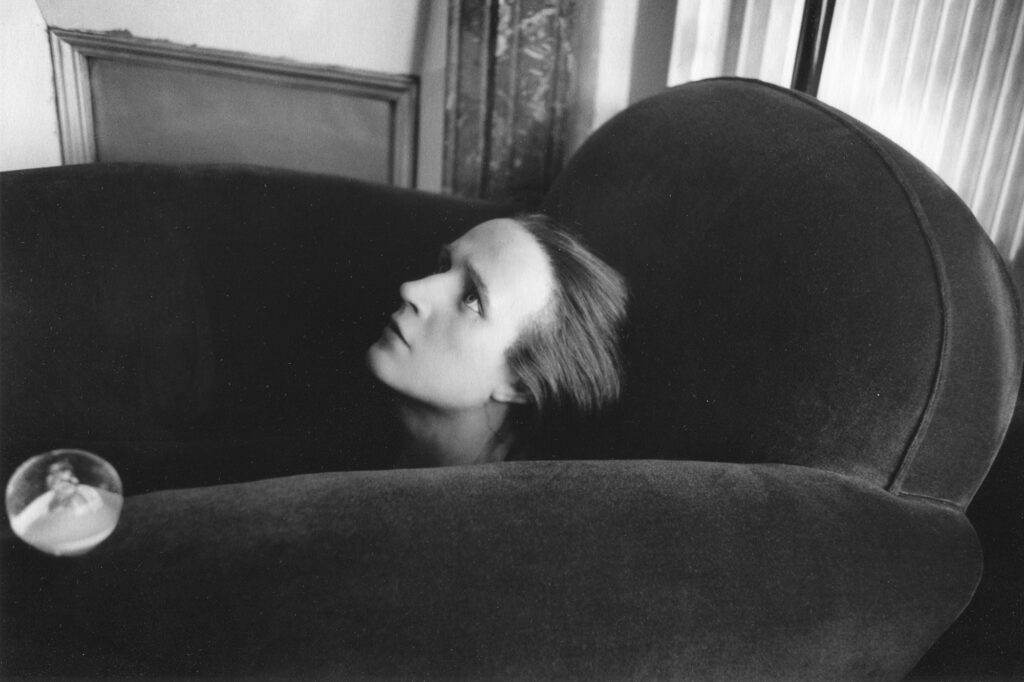

Very little of his photographic work has been published or exhibited in the United States, so the larger body of work remains rather elusive. Still, much of what has appeared is striking: emotionally warm, even a bit sentimental at times, but stylistically cool and confident. His images range from artful interiors and landscapes to pictures of friends, family, and lovers. The mood is usually hushed and intimate. Working in a distinctive black and white that tends toward soft platinum grays, he made what feel like visual diary entries, quick but thoughtful notes, often recording his immediate surroundings—his desk, his mantel, his bookcase—with the same descriptive intensity he brought to photographs of boys in his bed. Even in his most seductive self-portraits, Guibert never seems show-offy. The work is restrained and subtle—as if it were made not with a public in mind but for himself and a small circle of friends. We often feel we’re peeking into a private and somewhat privileged world, where much is revealed and just as much withheld.

In Ghost Image, a 1982 collection of Guibert’s brief essays on photography, reissued this year by University of Chicago Press, he writes about photographers he admires. They’re an idiosyncratic pantheon that includes Diane Arbus, Pierre Molinier, F. Holland Day, George Hoyningen-Huene, and Duane Michals, the last of whom seems especially influential on the selection of images included here. Clearly, he looked long and hard at his precursors and his contemporaries, but some of his most telling essays are dialogues with his critical self, an accusatory voice that he never allows to have the last word. When that voice points out that much of his work “oozes homosexuality,” he shoots back:

“How could it be otherwise? It’s not that I want to hide it, or that I want to boast about it arrogantly. But it’s the least I can do to be sincere. How can you speak about photography without speaking of desire? If I mask my desire, if I deprive it of its gender, if I leave it vague . . . I would feel as if I were weakening my stories, or writing carelessly . . . The image is the essence of desire and if you desexualize the image, you reduce it to theory.”

Guibert’s criticism can stray into knotty intellectual territory, but he steers clear of dry, deadening theory. What’s most engaging about his work in writing and photography is its frankness and sincerity—qualities the contemporary avant-garde has little use for. Even his restraint feels passionate—an elegance at once instinctive and hard-won.

All photographs courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts, New York