Hervé Guibert’s Seductive Photo-Novel About Two Sisters in Reclusion

The influential French writer’s book “Suzanne and Louise” is an intricate choreography of privacy, revelation, and performance, keenly testing the possibilities of its hybrid medium.

Hervé Guibert is best known for autobiographical novels, such as To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1990), published the year before he died from AIDS-related complications at the age of thirty-six. But Guibert was also passionate about another means of turning life into art: photography. This is evidenced not only by the many recent exhibitions of his work and his essential book Ghost Image (1982)—a carnal response to Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida—but equally by the photo-novel Suzanne and Louise, first published in 1980 and finally now appearing in an English translation by Christine Pichini. As Moyra Davey notes in her introduction to the new edition, the book is “a prized rarity” in that it is Guibert’s “only monograph where his full gifts as an image maker and as a writer combine.” The nature of that combination is at turns seductive, touching, and clever—but it is never straightforward.

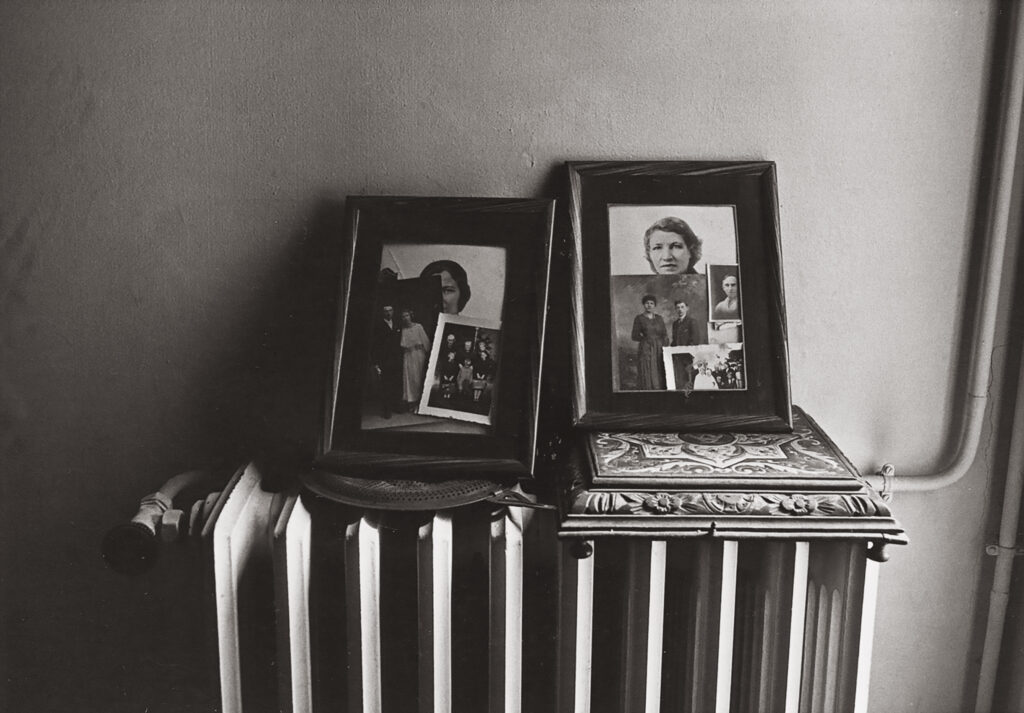

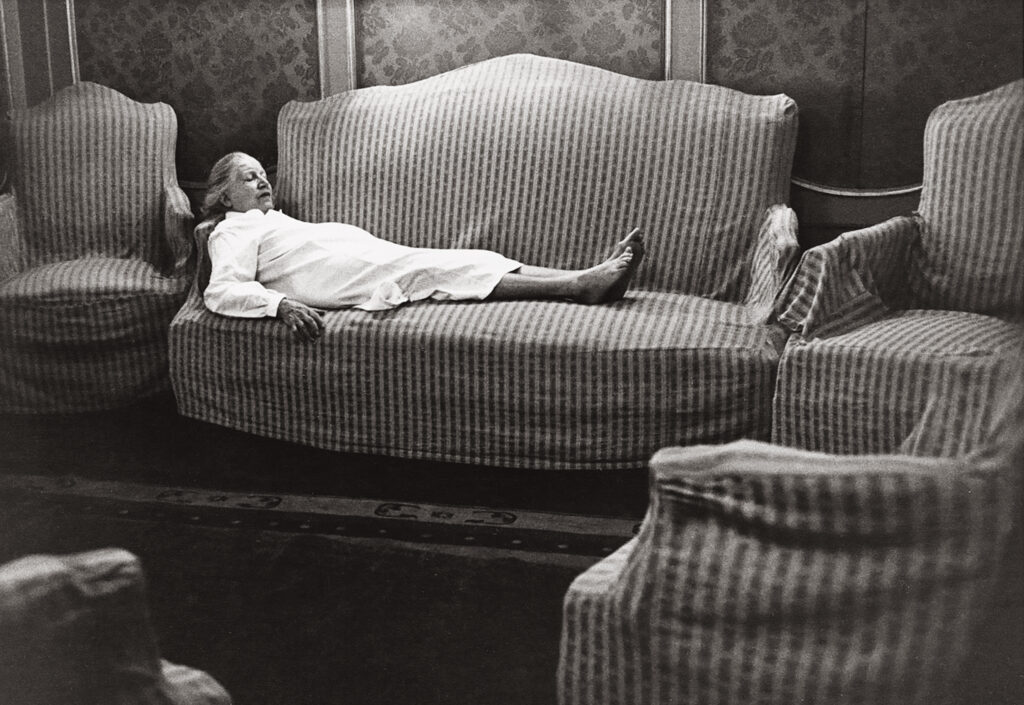

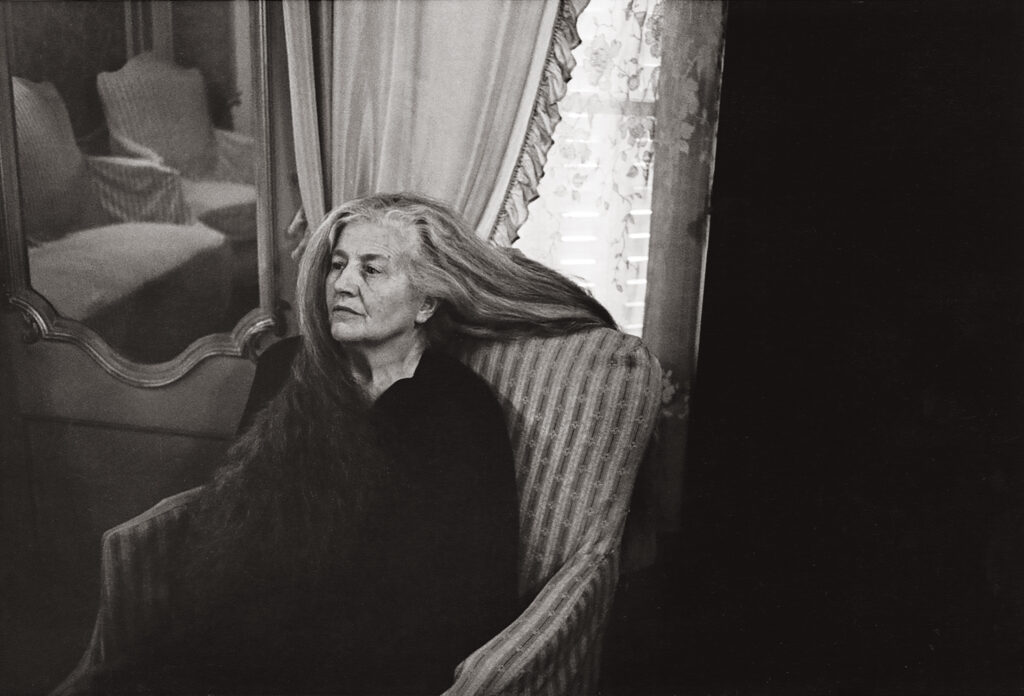

Suzanne and Louise is a story of devotion and desire. Almost all its images are domestic portraits of the titular sisters, the author’s great-aunts, who live together in a hôtel particulier in Paris’s fifteenth arrondissement. Guibert tells the tale of these women and offers glimpses of their lives, defying their idea that “old age isn’t presentable.” The pictures are posed but devoid of any great artifice; they possess a candor that is telegraphed above all by how often the pair is seen with their long gray hair—“the most intimate thing,” Guibert writes—set free to flow down backs that stoop with the weight of years. Ingenuous disclosure, one might think. While this would not be entirely wrong, the book’s first image points in a different direction. It depicts not Suzanne and Louise but studio portraits of each woman at a younger age, both of which are partially obscured by other images tucked into their frames. Likenesses multiply; any direct access to the pharmacist’s widow and the ex-Carmelite nun splinters into a field of competing depictions. This initial photograph of photographs is a clue that, rather than an immodest divulgence, Suzanne and Louise will be an intricate choreography of privacy, revelation, and performance, keenly testing the possibilities of its hybrid medium.

Guibert is known for telling all, for dragging all his life into the frame without shame, in ways tender and brutal. In La pudeur et l’impudeur (1992), his sole moving-image work, he subjects his emaciated body to the camera’s stare. Suzanne and Louise, intermittent protagonists in their grandnephew’s oeuvre since the photo-novel twelve years before, also appear in the video, fielding questions from him such as “Do you want to live or do you want to die?” (Suzanne’s answer: “It depends on the moment.”) This refusal to accept normative prescriptions of what deserves a place within representation—and what does not—sits at the heart of Guibert’s AIDS autofictions, and is no less present in Suzanne and Louise, despite its radically different subject matter. The book likewise plunges into an everyday that might otherwise be invisible, into lives lived at a distance from the heterosexual family and in palpable proximity to death. The intergenerational bond between the queer twentysomething and his great-aunts short-circuits patriarchal authority.

The book’s texts have a diaristic quality that is heightened in the French edition, where they appear in Guibert’s own handwriting, tethering word to body. Yet alongside Suzanne and Louise’s many inscriptions of presence is a predilection for absence, dream, and fantasy—in other words, for fiction. The German shepherds Whysky and Amok are central to the text but remain unseen, with their only visible trace coming in two anomalous pictures in which Louise poses with their muzzle over her face. In an echo of Ghost Image, there are descriptions of nonexistent photographs, missing images that haunt through words. And as the book progresses, a complicated account unfolds of Guibert’s shifting attempts to represent his great-aunts across media, from an unrealized film and a play never publicly performed, to an exhibition that ultimately sparks the creation of a photo-novel that concludes with fragments of a script for a new movie. Plans change in response to myriad factors, not least of which is the women’s reticence to have the details of their cloistered existence made known. By the end, it is clear that the entire enterprise has been one of tremendous complicity, a conspiracy of three more than an unobtrusive picturing of two.

“I am afraid of spiders, but not afraid of the presence of the dead,” Guibert writes. That presence is everywhere throughout Suzanne and Louise, and not only because the women are getting on in age. Guibert describes images never taken of a euthanized Whysky; he offers multiple evocations of Suzanne’s death, whether in a dream, a series of staged photographs, a film script, or the idea of one day photographing her corpse. He clings to representation as a talisman that will ward off the inevitable—but to vanquish finitude, he must invite it in. The fourth protagonist of this singular work, a book caught between conceptualism and confession, is death itself.

Herve Guibert’s Suzanne and Louise was published by Magic Hour Press in 2024.