Highlights from From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola

Roxana Marcoci and Sarah Meister as told to Paula Kupfer

Grete Stern, Sueño No. 1: Artículos eléctricos para el hogar (Dream No. 1: Electrical Appliances for the Home), 1949 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola.

When German artist Grete Stern and Argentine photographer Horacio Coppola met at the Bauhaus in Berlin in 1932, Coppola had already made incursions into photography and film while Stern had done the same with typography and graphic design experiments. They became a well-known couple within the intellectual scene of Berlin, but when the Nazi party began to gain power, they departed for London, where they married, and later arrived in Argentina. Intellectual and literary circles in Buenos Aires celebrated their unique visions, and their first exhibition, in 1935, at the editorial office of the magazine Sur, was heralded as the arrival of modernism in Argentina. A current exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, presents their work separately, in keeping with their different practices and careers, but highlights instances of overlap: their collaboration on several books, and their experimental, if short-lived, graphic design and photography studio. After the couple divorced in 1943, Coppola abandoned photography, while Stern continued to make photographs for several decades and surrounded herself with contemporary artists. Here, curators Sarah Meister, who focused on Coppola, and Roxana Marcoci, who researched Grete Stern, offer comments and insights into key works in the exhibition. —Paula Kupfer

This article originally appeared in Issue 13 of the Aperture Photography App.

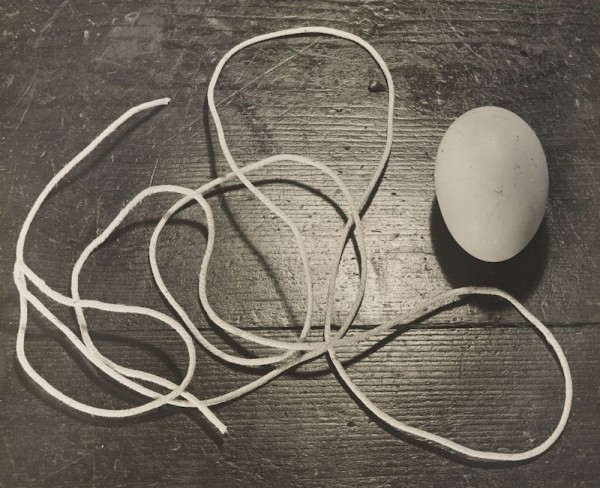

Horacio Coppola. Still Life with Egg and Twine, 1932 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

Sarah Meister: The first pictures by Coppola that I ever saw came in through the Thomas Walther Collection. We thought, that’s funny, an Argentine at the Bauhaus. This was in 2001 and we didn’t really know what to do. . . . We were pigeonholing him with the Bauhaus and not thinking of him as an independent artist. Then I started working with the Latin American–Caribbean Fund, which was helping support acquisitions of Latin American photographers, and with our C-MAP group [Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives in a Global Age Initiative, a global research initiative at MoMA]. I had the opportunity to travel to Brazil, to Argentina, to Mexico, and I started to see who the major figures were. The question became: how do you tell these alternative modernisms that are less familiar to an American public?

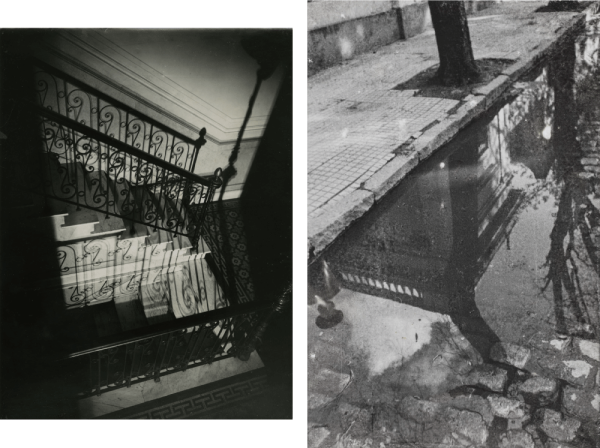

LEFT: Horacio Coppola, Untitled (Staircase at Calle Corrientes), 1928 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola; RIGHT: Horacio Coppola, “¡Esto es Buenos Aires!” (“This is Buenos Aires!”) (Jorge Luis Borges), 1931 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

SM: These are pictures (above and below) from before Coppola’s first trip to London. You already see the modernity. Then he gets a Leica and . . . these are what [publisher] Victoria Ocampo sees and publishes in Sur: “a modern vision of a city.” The problem with previous scholarship was that it put the achievement out there, but until you impose a strict chronology you can’t learn the sources.

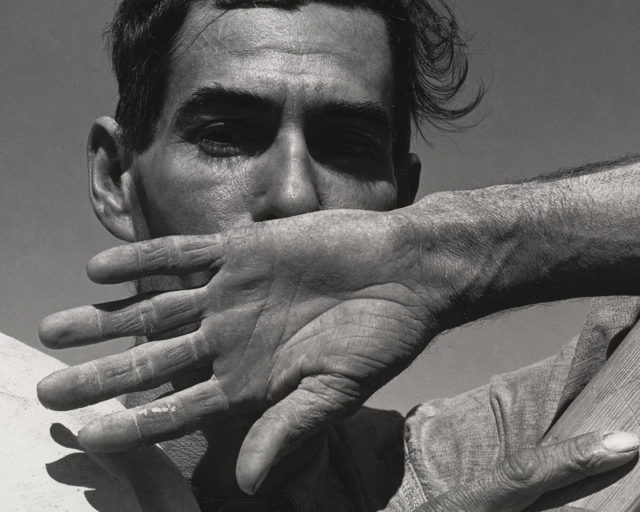

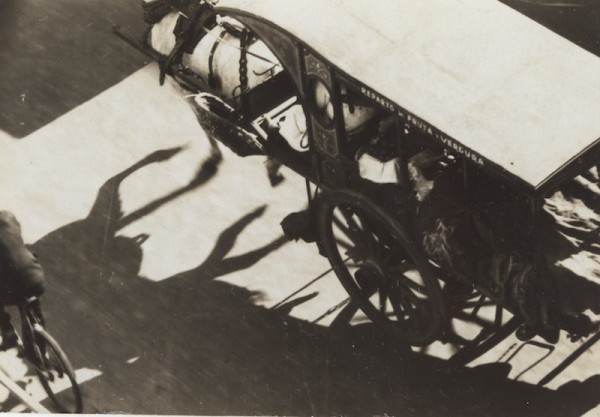

Horacio Coppola, Buenos Aires, 1931 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

This is one photograph that I love (above). I thought this was maybe a 3-by-4 negative, a contact print, since it’s unbelievably precise. I knew he’d borrowed his brother’s camera, but I didn’t know if this was in 1931 before he went to Europe or afterward. But I knew about the wonderful binders he made, of his favorite pictures—he literally took his 35mm-negative contact prints and pasted them in. Then I knew for sure it was a 35mm negative and I could place it in the context; I could see what he made before, what he made after. Like all good art history if you actually do your homework . . . and take the time to piece it together, it’s amazing, like detective work in the most satisfying way.

Installation view of From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph by John Wronn © 2015 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

SM: This wall shows Coppola’s photographs from his seminal book Buenos Aires (1936). I thought I would never in a million years hang this many pictures on a wall but actually . . . there was a moment in the installation where I thought, No, embrace it. Let the obelisk be the loose fulcrum, go from day to night. I knew I didn’t want to do a “day wall” and a “night wall.” I realized a few people might not get it, which is fine.

Installation view of From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph by John Wronn © 2015 the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Roxana Marcoci: For Stern, the show opens with this wall, which establishes the protagonists: we see Coppola, Ellen Auerbach, and Walter Auerbach, and others. Basically, Stern comes to Berlin extremely young, at the age of twenty-three, in 1927. Before that, she had already established a commercial studio in her hometown, and experimented with typography and advertisements; she was extremely precocious. So she comes right then to Berlin—which was the intellectual and cultural capital of central Europe—we’re talking roaring ’20s and the Weimar Republic. She becomes the very first student of Walter Peterhans, and then a year later, Ellen Rosenbach [later Ellen Auerbach] also becomes his student. [Auerbach and Stern] were very progressive. Both had been living with their middle-class, bourgeois families and they went to study and to Berlin. They experiment with film. And they all live together, with their lovers at that time, who eventually become their husbands.

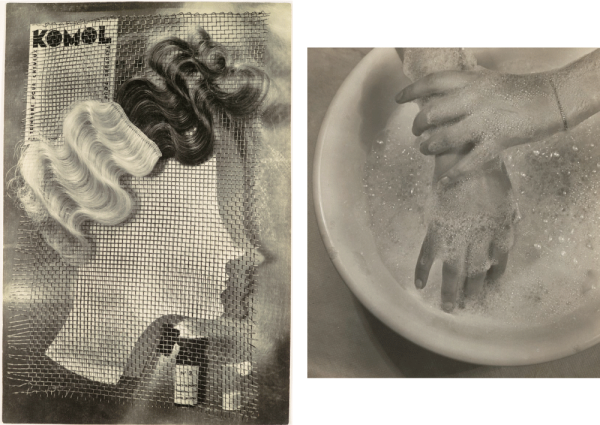

LEFT: ringl + pit, Komol, 1931 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola; RIGHT: ringl + pit, Soapsuds, 1930 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

RM: Stern’s sense of very close observation brought her to Peterhans—he is about the New Objectivity, the Neue Sachlichkeit strain in the Bauhaus, of very close observation. The other part of her is the sense of experimentation, of whimsicality, that comes through in the advertisements. She and Auerbach decide to form the ringl + pit studio. They are playful—they take [the name] from their nicknames from when they were children—Stern was Ringl, Auerbach was Pit—but also impressed both commercial and avant-garde loyalties. They decide to cosign the work; they spoof the cliché of the “master”—these are women who are working both in front of and behind the camera. For Stern, the whole psychoanalysis aspect in her work, the idea of opposition, of where you stand from and where you take the picture from, is a very feminist idea. While she never was an activist she was always affiliated with feminist and antifascist causes.

In this picture, for instance (above, left), there is this engagement with what is called the “Neue Frau” (new woman): she was considered the first global icon of modernity, as a woman and as an image of a woman. (In France, Coco Chanel was an example, and there’s the American flapper, too.) What’s nice about what they do is that they scramble a lot of gender signifiers and sartorial cues.

And in this one (above, right), they say they can’t even remember who took the picture and who is the hand. So this mix of animate and inanimate, which was dear to the surrealists, is also at play here. Interestingly, this [picture of soap] is one that Christopher Williams, with whom I did a previous show, was looking at. He has a picture of soap, too.

Grete Stern, Autorretrato (Self-Portrait), 1943 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

RM: This is one of the most revolutionary self-portraits. It’s a self-portrait as a representation in a mirror—she doesn’t even appear in it—and because of the combination of feminine and masculine props, the floral arrangement, which are also in other pictures of her, but also the mathematical instruments and then the mirror and the lens, which are visible in the foreground. Both mirror and lens function as tools of self-analysis.

RM: They [Coppola and Stern] divorced in 1943. They’d built a house, by Vladimiro Acosta, a very progressive architect, in the Ramos Mejía [neighborhood]. Grete kept the house, and it would become a mecca for a whole new group of writers and artists, including Madí.(Madí stands for materialismo dialéctico; they were a leftist group of artists who stood in opposition to Perón.) She designs their logo (above): she takes the existing neon sign for Movado watches and superimposes the three other letters in 3-D fashion, over the obelisk, partly because the obelisk is an abstract signifier and the Madí group was interested in abstraction. This Madí photomontage is the first acquisition that I made a few years ago—before we started working on the exhibition.

Grete Stern, Sueño No. 28: Amor sin ilusión (Dream No. 28: Love Without Illusion), 1951 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

RM: The last room is dedicated to the Sueños, from 1948 to ’51. Stern starts contributing on a weekly basis to the magazine Idilio. The rest of the magazine is these fotonovelas (photo–soap operas), very kitsch, but her work is very strong. The rubric “Psychoanalysis Will Help You” was written by two sociologists and a psychoanalyst under a pseudonym. She was making the photomontages on the basis of the analysis and the dream. What is interesting is that often her photomontages stand as a form of resistance to their interpretation of the dreams. This is a country where psychoanalysis has such a strong foot. Perón was against all of it; the psychoanalysts were blacklisted. This could only appear in a women’s magazine.

It’s interesting that in all these pictures the main protagonist is a woman, and the situation is always one of conflict; she has this very filmic mode of telling a whole narrative within a frame. This is where [the exhibition] ends, with her Sueños, because here, more than in any other bodies of work, the lessons of the Bauhaus laboratory—obviously advertisement techniques, and even typography—merge with this more Latin American, Borgesian sense of rupture and montage and different type of storytelling. When two cultures meet in this way, you can talk about a transnational modernist culture.

From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires runs through October 4 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.