A Lesson in Art History from Hiroshi Sugimoto

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Past Presence 070, 2016, Grand Femme III, Alberto Giacometti

© the artist; depicted artwork © Alberto Giacometti Estate / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris

When I was in college, sometimes when I wanted to blink away the rhythm of seminars and red Solo cups, I would go to the library and look at Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photobook Seascapes (2015), a complete collection of the artist’s series of the same name. I liked how the black-and-white photographs called on me to set my mind adrift as I flipped through more than two hundred images of tranquil seas. But they also asked me to lean closer, to pull the book two inches from my nose, to pay attention. Flipping back and forth from the Sea of Japan to the Aegean Sea, sailing between blacks, clouds, and froth-tipped wings on waves, I would enter, slowly, what I called “Sugimoto time.” His photographs raised questions of perception: What is sea but a plain of burlap, glass, wheat, sand dune? Do we look at seas differently than we do the sky?

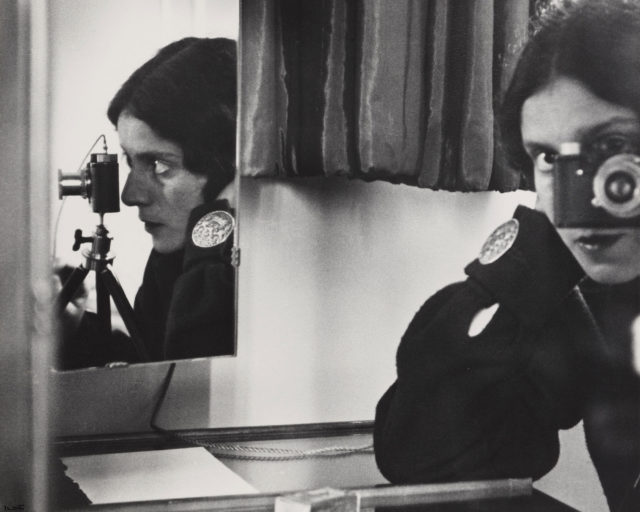

In Past Presence, Sugimoto’s current exhibition at Marian Goodman Gallery, I found my perception of form disrupted once again. Using a similar method as with his series Architecture, his subjects this time are modernist masterworks—photographed a little out of focus. I went to the show with a friend—we grew up together in Tokyo—and we walked among the photographs of blurry Brancusis, Duchamps, and Giacomettis. “What’s the English word for bokeh?” we murmured to each other, not the photographic term, meaning blur, but the word as semi-slur, flung by Japanese schoolchildren at kids whose heads were in the clouds? “Dimwits,” my friend said. No, there had to be something closer, that held the possibility of fondness. The equivalent of snapping fingers near someone’s ear, an appeal for a different kind of focus.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Past Presence 026, 2014, Head of a Woman, Pablo Picasso

© the artist; depicted artwork © Succession Picasso

I heard this snapping as I looked at Sugimoto’s photographs of Giacometti’s sculptures. In these images, Sugimoto demands a new way of seeing and questions traditional processes of memory recall. Giacometti’s bronze bodies and faces exist in their ridges and jags, scratched and formed by precise steel fingernails, far away from the soft pulp of flesh. But in Sugimoto’s photographs, the Giacomettis have the ambiguity of a dream—The Nose (1949) is blurred, looking like the profile of a tengu, a Japanese mask with a long, stretching nose. Its ridges and specificity are obliterated, leaving the softness of shadows. Refused the pleasure—or crutch—of detail, I walked back and forth in between photographs, noting how they resisted each other. Paintings, like Picasso’s Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907) are notably small-scale, contained, while Brancusi’s sculptures loom large and centered in the photograph. In the exhibition, Sugimoto challenges our collective memory of these figures, allowing us to plunge into the haze of remembering and question whether paintings are stamped differently in our minds than sculptures—why do we remember Giacometti’s figures as rigid, instead of soft?

When we looked at Sugimoto’s Portraits, his photographs of wax figures from Madame Tussaud’s, we gorged ourselves on detail—the glossy plushiness of Oscar Wilde’s coat lapels, the eerie blankness of Anne of Cleves’s eyes in relation to the glint of her pearl embroidery. I could linger on the protruding veins of the Duke of Wellington’s wax hand, but I could also walk on to a portrait of a waxen Takeshi Kitano, who, if I turned on a TV, would be alive and flailing his arms in his usual frenzies of locution. Portraits overwhelmed us with specifics, asking us to summon how we remember people—people deemed “historical” in our present—and prodded the distinctions between real and unreal, human and unhuman. If the hyperrealism of the portraits of wax figures played with the aesthetics of portraiture (what makes a portrait great? what details are emphasized in the subject?) then the blur of Past Presence, by refusing the viewer many of these things—people, movement, even detail—compellingly deals with the questions of abstract art. It’s sometimes hard for me to imagine Sugimoto, a master of his craft, as a boy, newly smitten with cameras, taking photographs of trains and sneaking into cinemas, angling his lens at Audrey Hepburn. But I like that story, because it, too, aligns neatly with the concerns of modernism: a revolution in our understanding of speed and distance, an obsession with tinkering with the mediated image.

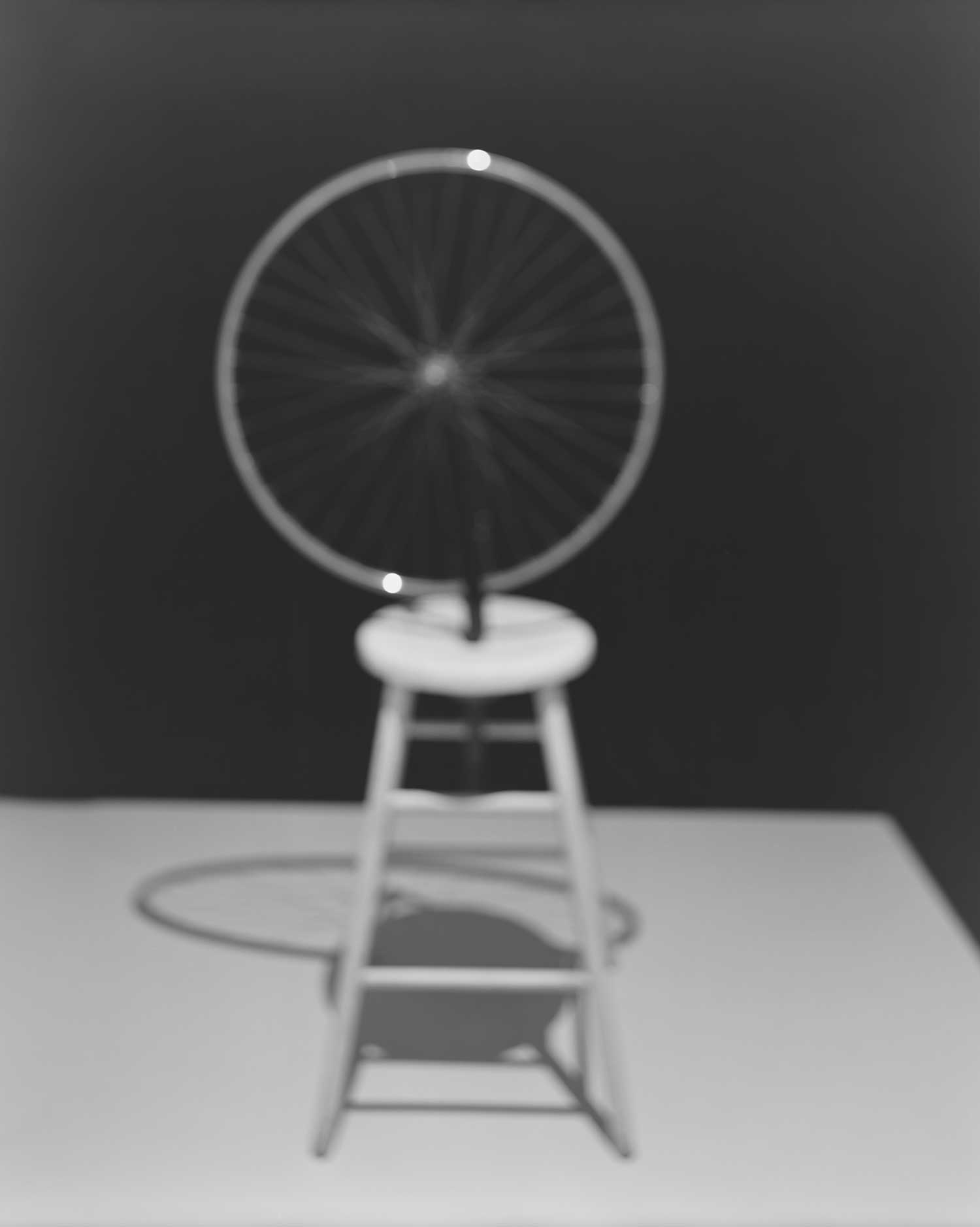

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Past Presence 025, 2014, Bicycle Wheel, Marcel Duchamp

© the artist; depicted artwork © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

After a few rounds, I settled in front of Sugimoto’s photograph of Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1951), and I was brought back to college. In a class on modernism, a professor had thrown a photograph of the artwork on a PowerPoint slide—the way that most of us who don’t live in New York first interact with modernist masterpieces—and told us to comment on what we saw. A quiet girl raised her hand, tentatively, and started talking about how it made her pay attention to the interaction of the different curves—those of the wheel, the stool, and the shadows. The professor dryly suggested that we should be talking about the object (the art itself), not the photograph; the shadow, the professor said, wasn’t part of the artwork. Looking at the Duchamp through Sugimoto’s eyes, I could almost hear Sugimoto’s gentle answer to that professor: “Look more carefully: what, you think art doesn’t cast shadows?”

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Past Presence is on view at Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, through October 26, 2019.