How Are Young Photographers Documenting the Protests in Hong Kong?

The Hong Kong protests hold a strong grip over the public imagination. Even if you’re only a passive observer of the news, the demonstrations will most likely conjure at least one of these images: clusters of umbrellas, tear gas raining down over yellow hard hats, masked protesters hurling Molotov cocktails, black-clad crowds flooding onto freeways, police firing blue dye from a water cannon against Hong Kong’s iconic skyline.

Courtesy the artist

These are undoubtedly some of the most defining moments in the city’s historic uprising, whose mass demonstrations began in June 2019. They capture the fiercest scenes as Hong Kongers fought for the city’s rapidly deteriorating democratic freedoms. As a former British colony, Hong Kong inherited special civil liberties when Britain returned the territory to China in 1997, forming the backbone of a remarkably unique and vibrant society on communist Chinese soil. After years under threat, the fight for democracy erupted last June over a now-withdrawn extradition bill proposed by the Beijing-backed government, which would have allowed Hong Kong criminals to be sent to mainland China for trial. The furor evolved into a wider movement for democratic reforms that is now in hibernation amid the coronavirus outbreak.

Courtesy the artist

When an entire city is convulsing, as a photographer, the challenge becomes one in finding meaning beyond the immediate mayhem. The protesters’ clarion call was “Be water,” a Bruce Lee–inspired catchphrase that made confrontations forceful, fluid, unpredictable, and nonstop. It also made the protests felt in every corner of life in Hong Kong, no matter race or class or neighborhood. When a movement is so charged and all-consuming, how do you transcend the news, capture something quieter, and say something bigger? From documentary to the conceptual, several young Hong Kong photographers endeavor to create images that capture life and identity beyond the front line.

Courtesy the artist

Billy H. C. Kwok was on assignment when Hong Kong first came to a halt. It was peak morning rush hour on August 5, 2019, on the subway when protests took a new turn: a general strike. With the government refusing to concede to any demands, protesters across the city used every means necessary to block the entrances of train doors—umbrellas, fire extinguishers, bodies, backpacks—and freeze the subway. Kwok had been covering the protests since the first canister of tear gas was fired in June. Up until this point, protests had meant action in the streets.

Down on the subway platform, Kwok was unsure how he could photograph such a static moment. Kwok looked around and observed all the faces and emotions of commuters trapped in the train cars. “People were not used to the protests in this way,” says Kwok, one of several young photographers I spoke to recently. Any disruption to Hong Kong’s renowned public transportation and work-driven way of life is jolting, and he could see it in everyone’s expressions. Through the glare and dirty subway windows, Kwok captured Subway Strike (2019), a series of portraits of individuals looking at their phones, quietly staring off, deep in their thoughts—trying to go about their everyday lives yet caught in the crossfire.

“I’m trying to step back and see the protests as a social landscape for Hong Kong,” says Kwok.

Courtesy the artist

With a similar photojournalistic background, Kenji Wong also pushed the creative boundary with his color-heavy project Hello darkness, my old friend (2019). From landscapes of Victoria Peak illuminated by laser pens and flashlights to a rainbow beneath a water cannon pummeling protesters, Wong created high-energy pictures that glorify the movement.

Wong was particularly interested in photographing the humanity and solidarity of the movement. People have a “certain impression about the protesters,” he says, referring to the stereotype of the Hong Kong protester—a young, masked, violent man. “But behind the mask, they are also teenagers. They’re Hong Kong people, they’re human. They do normal things that normal people do.”

In his work, Wong strives to capture the diversity of emotions and participants. The night after a university siege, protesters stayed up all night on a bridge to watch the sunrise, where Wong caught a young couple kissing. In another, Wong captures a chain of young female students in their school uniforms holding hands in a human chain, a popular form of nonviolent protest that at times would span the entire city.

Courtesy the artist

With CCTV cameras and Beijing’s lurking presence everywhere, fear of surveillance turned masks into the protest uniform. From the streets to the internet, protesters became extremely suspicious of being photographed. So as a street photographer, Etienne Leung struggled to capture those daily moments. Instead, she opted for a more indirect, cinematic approach, using black and white to enhance emotion and a wide-angle lens for more impact.

One photo from her untitled series captures a protester who had just broken into Hong Kong’s Legislative Council Building, framed by a broken pane of coincidentally heart-shaped glass. Another captures a protester running into a beam of light on the highway bouncing off the city skyline. “It’s not like all the explosive moments of police brutality,” says Leung. “It mimics that sense of hope within a youngster’s heart.”

Courtesy the artist

Another major governing force of the protests: the internet.

Unlike the pro-democracy protests in 2014, known as the Umbrella Movement, the 2019–20 Hong Kong protests were—and still are—leaderless. For fear of surveillance and individual retribution, protest actions have been governed anonymously online, especially via Telegram, an encrypted messaging app. The cybersphere as a public forum creates a whole new dynamic for forging relationships among protesters and strangers.

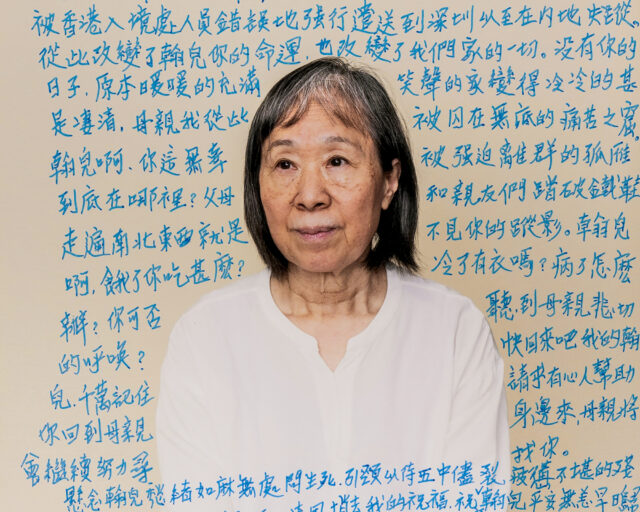

Courtesy the artists and WMA, Hong Kong

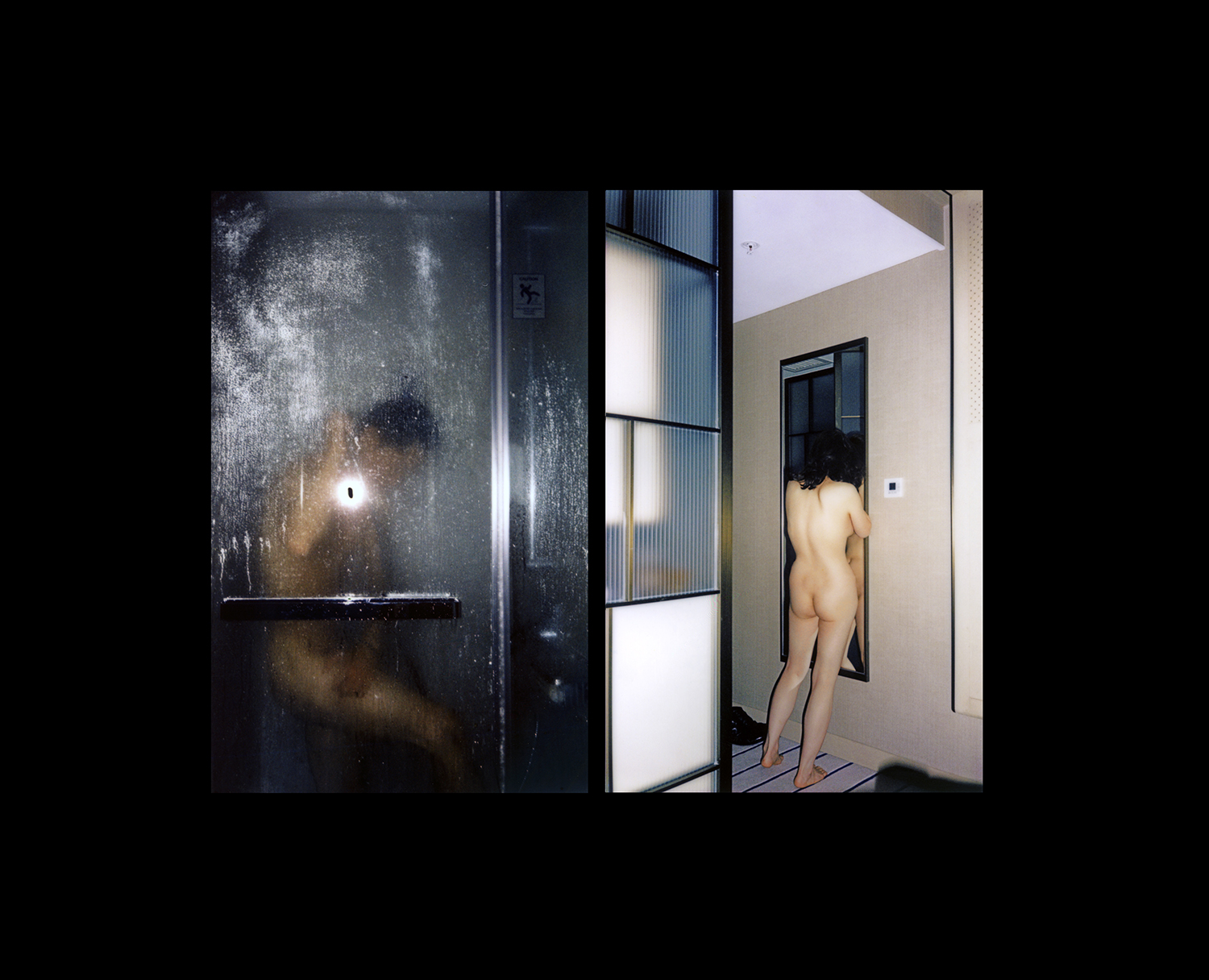

This concept formed the basis of the 1/8 series—a finalist for the WMA Masters prize, an annual photography initiative supported by the Hong Kong–based WYNG Foundation—by two photographers who go by the pseudonyms O’Young Moli and Julian. The two found each other as kindred spirits online. But then the protests erupted, and they could never find the time to meet in person. The movement calls for five major demands, including an investigation into police brutality and direct elections. While the government met one of these demands by withdrawing the extradition bill, O’Young Moli and Julian joked that they should meet only after a second demand was met—an unlikely possibility.

So they began an experiment: until that goal was achieved, they would only meet in person in a dark room. To mimic their impressions of each other online, they would only see each other’s faces through the light flashes of an instant camera. The result is a photo series of disjointed, semiabstract snaps—of ceilings, curtains, cluttered desks, faceless bed-lounging, and nude backsides. The series speaks to the random yet intimate nature of online relationships amid the unrest.

Courtesy the artist

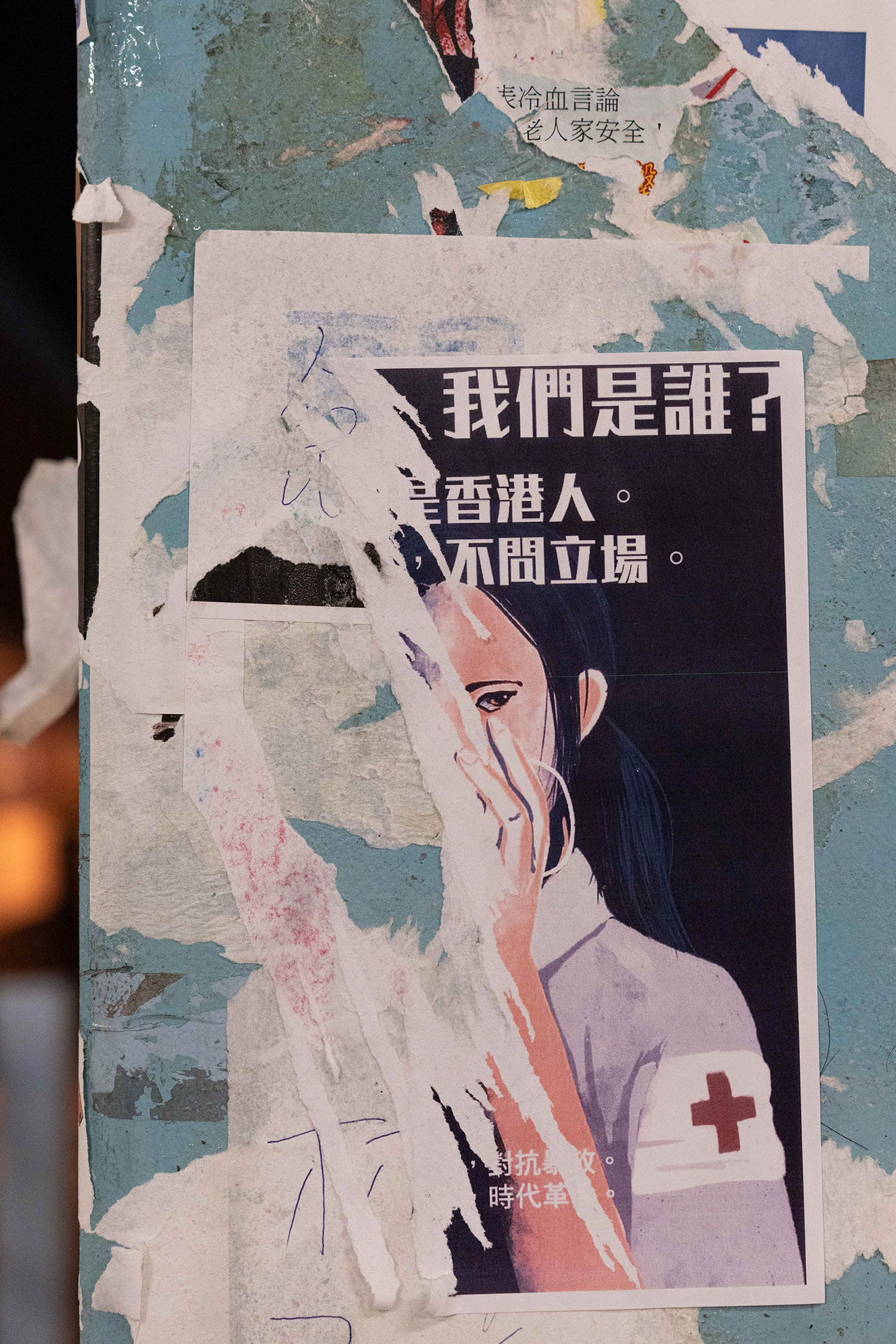

In a similarly conceptual project, Wong Ka wing set out to document the so-called Lennon Walls of the movement. Since the protests kicked off in earnest last June, Lennon Walls have been one of their defining features. Every public wall space—from tunnels to footbridges to staircases—burst to life as a mosaiced message board, fluttering with neon-colored Post-its and graphic posters calling for action against the government and voicing grievances over police violence. Inspired by the original 1968 pro-democracy graffiti wall in Prague, which was later named after John Lennon to symbolize freedom of expression in the 1980’s, Hong Kong’s Lennon Walls first emerged in the 2014 Umbrella Movement and became a key protest barometer in 2019.

As a public display of outrage, Lennon Walls became flashpoints between pro-democracy and pro-government groups, leading to droves of opposition groups calling to tear down the walls. The role of the walls as an extension of the conflict fascinated Wong, especially the irony of it all. To justify their removal, the opposition argued the Lennon Walls made Hong Kong look ugly, when what was left behind was even messier.

The opposition has the mindset of, “if I destroy the wall, the movement will fade away,” says Wong. “That’s ridiculous. The poster is just paper. To destroy it does not tackle the problem.”

Courtesy the artist

The act of tearing the walls down also inadvertently added several layers of meaning in Cantonese. For example, one Lennon Wall poster showed an image of an elderly woman being pepper-sprayed in the eye by police. The image is significant, because protesters repeatedly posted it online while opposition groups repeatedly reported it. Wong likened the act of ripping down the poster to “attacking the older woman.”

After another ripping spree, all that remained of a different poster—commemorating the five-month anniversary of the Yuen Long attack, when a gang of white-clad men wielding rods and poles assaulted passengers in a subway station—was the character for the number five. Wong likened this to the removal of time; there was no end to their anger. “After the damage, it shows the event will never fade out, it is still here,” says Wong. “After the damage, it’s even stronger.”