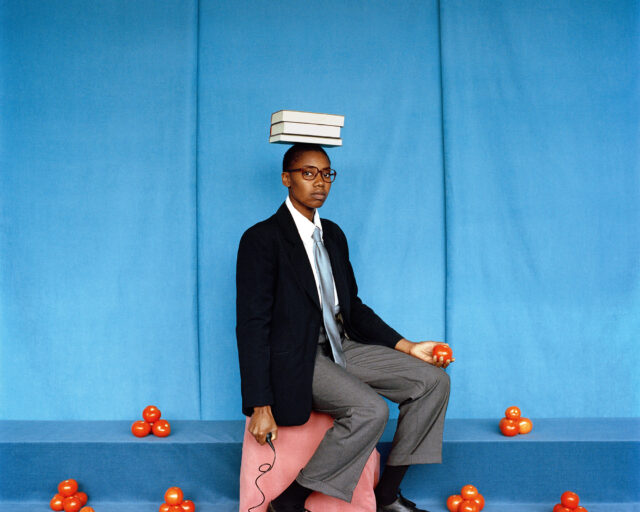

Tamara Abdul Hadi, Best friends in Chabayish, 2018

Iraq’s capital has endured waves of violence, from civil unrest to foreign invasions, leaving little room for arts infrastructure. But the launch of Baghdad Photo Week, the country’s first photography festival, marks a notable turning point. Organized by the photographer Aymen Al-Ameri and his partner Meena Alyassin, who also cofounded the Iraqi arts magazine Henna, the event took place last December at The Gallery, a commercial art space in Baghdad.

The festival’s theme, “Forgotten,” paid tribute to two pioneering Iraqi photographers of the past, Nadhim Ramzi and Hadi Al-Najjar—key figures, alongside Latif al-Ani, in establishing the medium in the country. Much of the photography on view carried an aesthetic shaped by conflict and melancholy. Al-Ameri, Amir Hazim, and Alhassan Jamal Aldeen each capture daily life in high-contrast black and white, depicting ecological pollution, antiestablishment protestors, and the month of Muharram, the start of the Islamic New Year when Shias mourn Imam Ali, whose face is plastered on every street corner.

The program aimed to foster collaboration between diasporic Iraqis, image makers from throughout the country, and international photographers such as Charles Thiefaine, who is based in Paris and has made work about the massive 2019 protests in the capital that left hundreds dead, the subject of his project Tahrir Disobedience. Another body of his work, Ala Allah (On God), offers a quieter, warmer portrayal of daily life in Iraq —a more humanizing view than typically seen abroad.

The wide accessibility of photography, which requires little more than a smartphone, has accelerated its growth in Baghdad. With more photographers emerging, the need for a communal space to share images has become crucial. Al-Ameri, the festival organizer, is committed to working with photographers to develop a diverse range of projects. “We have many good Iraqi photographers, but most of the pictures are of the marshes and Karbala,” he told me, referring to Iraq’s southern marshlands and the Shia pilgrimage city. “We need to see more exhibitions. We donʼt have many galleries, and most photographers are stuck in the same cycle.”

The need for a communal space to share images has become crucial.

Documentary photography remains dominant, shaped by heavy international coverage of wars in Iraq. Abdullah Dhiaa Al-Deen’s work is notable for capturing pivotal political moments and social issues with striking honesty. Professional photography in Iraq often prioritizes income potential over artistry, reflecting the country’s high unemployment rates. Bearing witness to decades of tragedy has been central, but now, with the country’s relative stability and recent urban development, visual narratives are evolving.

Coming to Iraq for the first time as a war correspondent in 2015, Thiefaine noted that many international journalists reproduced similar imagery. “I started to realize there was a big gap between what international photographers show and the lived experience,” he said. Befriending Iraqi youth, Thiefaine noticed that people were very open to being photographed. “Even during the protest, people wanted to show what they have in mind as a society. They were proud of what they were trying to do. I try to stay far from the imagery of violence in my personal work.”

Thiefaine believes that although Western journalism has contributed to shaping Iraq’s maligned global image, the “political situation is changing very fast, which brings about new representation,” pointing to different subcultures, queer culture, and how the festival itself aimed to show diverse perspectives. With Iraq frequently cited as one of the world’s fastest-warming nations, environmental concerns also drove projects on view, such as Tamara Abdul Hadi’s pictures of the iconic marshes and the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, as well as Emily Garthwaite’s photographs of Kurdistan’s biodiverse landscapes and minority communities, including Yazidis, Zoroastrians, and Bahá’ís.

Female representation in Iraqi photography is growing, albeit slowly. Initiatives such as Iraqi Female Photographers, founded by Ishtar Obaid, spotlight women, including Asmaa Turki, Saba Kareem, and Tiba Sadeq. Turki’s work ranges from young ballerinas in Baghdad to serene abaya embroidery in Najaf, vitalizing traditional themes with quiet beauty. Kareem’s images of the marshes and pilgrimages add to this expanding repertoire.

Al-Ameri organized Baghdad Photo Week with minimal funding—an impressive and steadfast effort emblematic of the Iraqi attitude to life. “Habibi, send me photos right now, let’s talk tonight,” he recalls saying to friends just months before the festival. “To deal with Iraqis is not easy,” he added. “Everything is al Allah [with God],” a phrase symbolizing a relaxed approach to deadlines. Creative problem-solving became vital for handling damaged prints and mismatched frames. Censorship presents another challenge. Political content, nudity, and drug-related themes are taboo. Social media offers some freedom, but constraints still limit expression. Despite Baghdad Photo Week’s groundbreaking success, significant obstacles remain. The country’s cultural infrastructure is underdeveloped, with minimal arts education, scant media coverage, and few exhibition spaces. Yet Baghdad Photo Week highlighted not only Iraq’s wealth of talent but also its need to rebuild an artistic community and, after decades of relentless conflict, reimagine its global image.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads,” under the column Dispatches.