How Have Photographs Shaped Our Idea of Work?

An exhibition contends with the role of images, policy, and activism in forming our relationship to labor and the American Dream.

Per Brandin, Office Cubicle and Plant, Olympus Camera Corp, 1979

© the artist

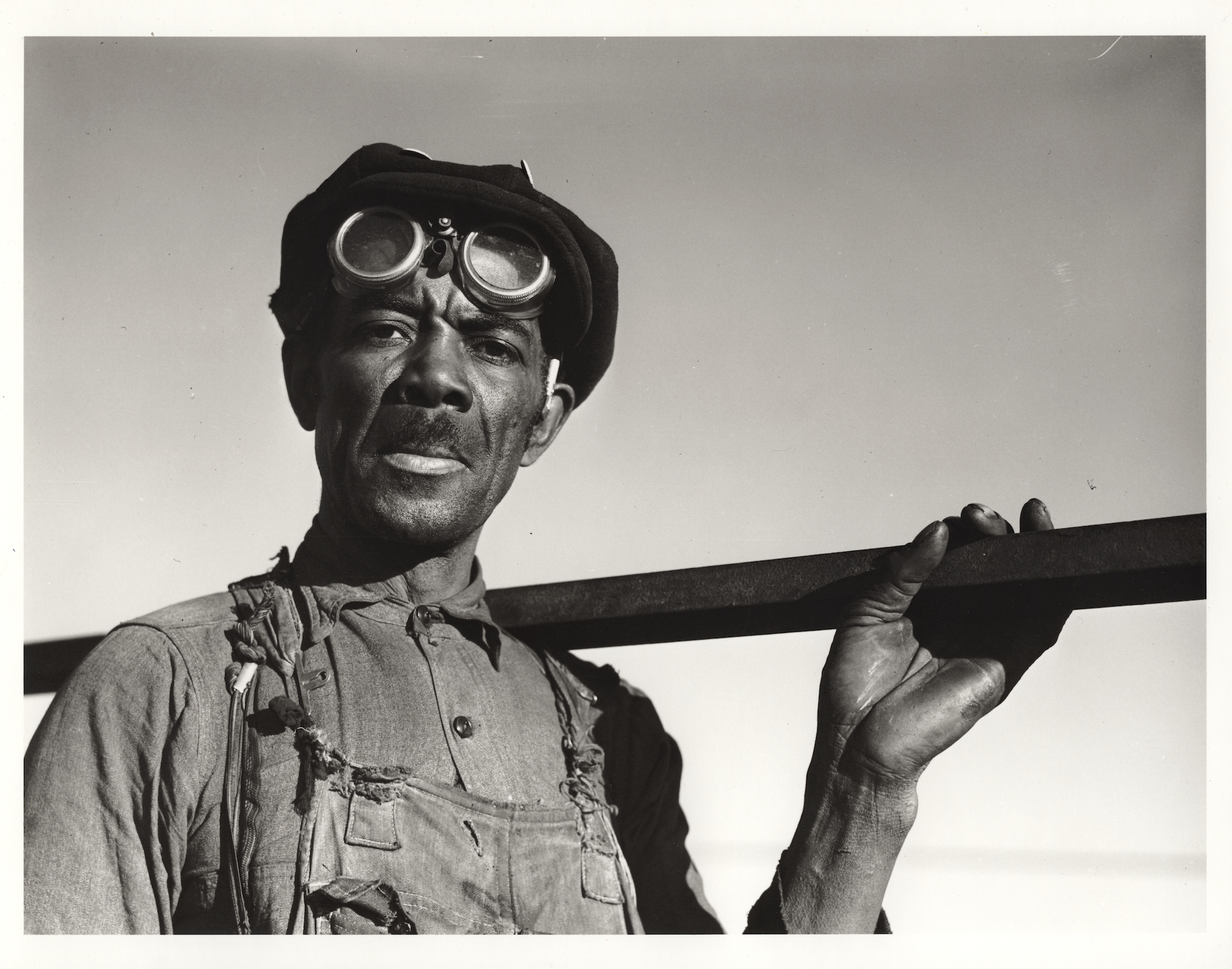

A good job is inextricably tied to the mythology of the American Dream, and is often thought of as a central component to one’s identity as an American. These considerations are particularly resonant in this very moment, as labor in the United States encounters pressures from the policies of the current administration and the rise of AI. The exhibition American Job, curated by Makeda Best at the International Center for Photography (ICP), New York, contends with these complexities through a layered historical lens, revealing the deep connections between labor, activism, policy, and the American imagination. Through photographs dating from 1940 to 2011, the exhibition tracks the transition of the American job from manufacturing to service industries while also sharing its deep links to activism and the role of the camera in its documentation. With such a rich range of works spanning several generations, serious issues beyond the timeline of the exhibition become exposed. These include the impact of photographic advocacy in a saturated and dispersed media landscape, the concerns of image verifiability in the age of AI, and the general lack of visibility of labor in contemporary America. Earlier this year, I spoke to Best about the project.

Ben Sloat: How do you see the relationship between the American job and the American Dream in this exhibition?

Makeda Best: What I enjoy about the exhibition is that there are different interpretations of the American Dream. The photographs present broad interpretations of access, opportunity, and agency. In some photographs, the American Dream is presented as the realization of collective labor as a political force. In others, it is associated with consumerism. The exhibition outlines the influence of mass media, like Life, which in the 1940s tried to place workers within its broader portrayal of the American Dream as it was linked to participation in the consumer economy. Workers were viewed as potential consumers.

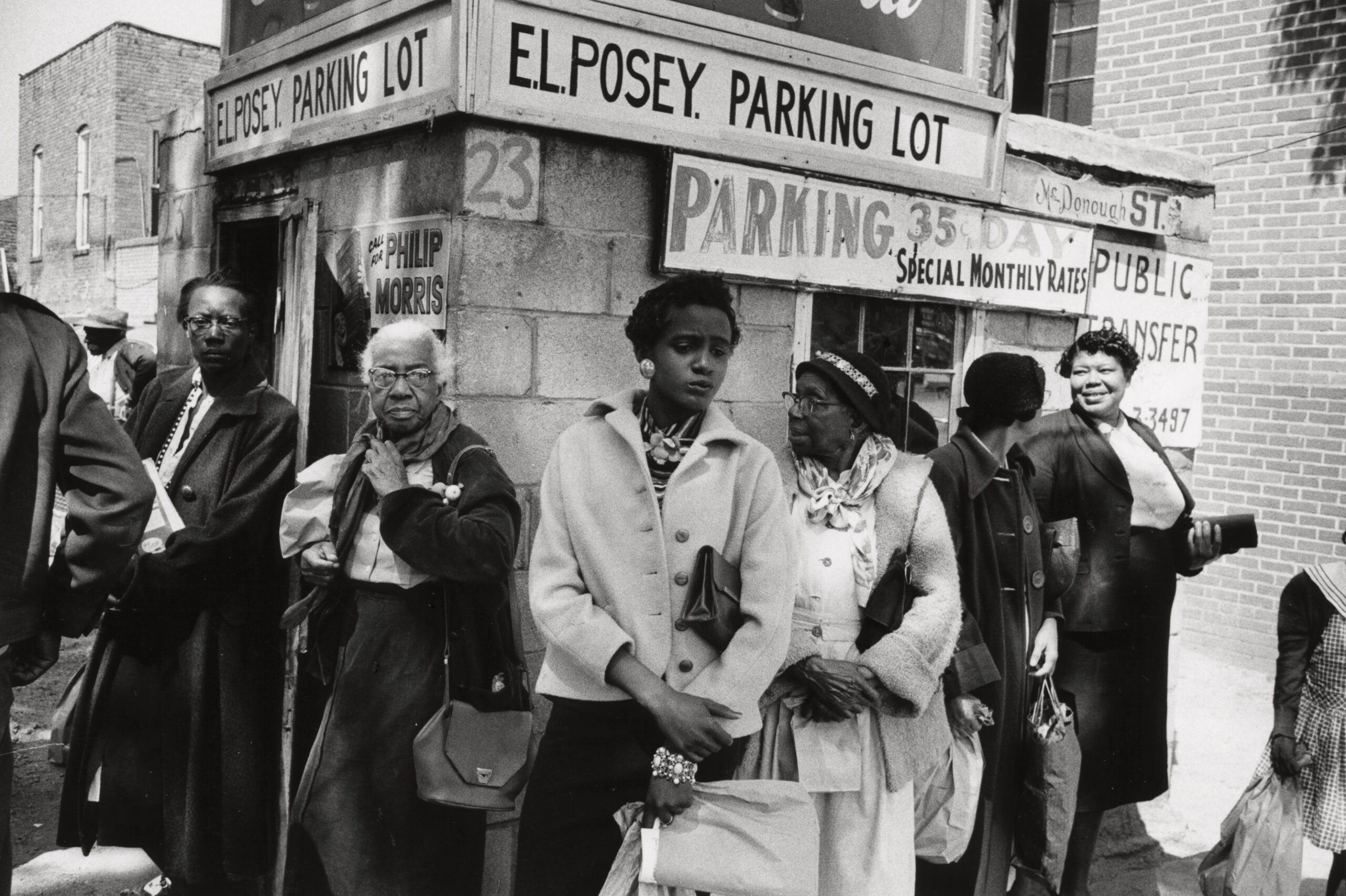

The American Dream is inextricably coupled with American ideals of freedom and justice. African American veteran strikers in John Vachon’s photographs questioned a system that did not treat them as full citizens. There are photographs of John F. Kennedy, where you get a sense of how he embodied—or was “selling” as—a youthful, handsome, successful man, an American Dream. In one of my favorite photographs, Gordon Parks’s picture of the debris on the Lincoln Memorial after the Poor People’s March of 1968, there’s a sense of questioning of how lower and working class people have access to American Dream.

Courtesy the International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos

Sloat: What drove you to develop the show?

Best: The meaning of work to one’s personal well-being and the role of work as part of the social fabric of a community has been an ongoing personal interest. I also wrote a book about the Civil War, Elevate the Masses: Alexander Gardner, Photography, and Democracy in Nineteenth Century America (2020), which was concerned with the connection between labor and democracy. But a more contemporary inspiration was Dawoud Bey’s photograph, Two Young Men at Carrollsburg Place, Washington, DC, 1989, which I included in Time is Now: Photography and Social Change in James Baldwin’s America, my 2018 exhibition at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I’m fascinated by symbolism of the two young men in that photograph, and have always thought of them as in-between different economic, social, and political realities. I also thought of them in conjunction with a book by William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (1996), which very much relates to the world those two young men were inheriting. My original plan for this exhibition was to start in the ’90s and move to the present day, as I personally felt that this era represented a turning point for the American workforce.

But as I started research into the ICP’s collection, I became interested in a different version of labor in America. In the collection there’s a focus, especially in the work from the 1940s–60s, on honoring the visions of photographers and photojournalists, and on respecting the work that they do. And there are so many different kinds of photographs. These ideas of labor and class that I had already been thinking about provided the perfect context to present the work of these photographers in conversation with each other. And I realized the story needed to start earlier, to show a shift in the function of photography, photojournalism, and media in American society over the twentieth century.

© Todd Webb Archive

Courtesy the International Center of Photography

Sloat: As you were going back in time with your research, what were some of the inspirations that allowed you to shape this idea, and how did you come to have five sections for the show?

Best: I chose to bookend the exhibition between World War II and the end of the second Gulf War in 2011. These dates are significant to photography as well, tracing the movement from the heyday of photojournalism to the cusp of the social media era. It’s also a period of dramatic economic shifts, and those shifts are tied to how armed conflict shapes national trends in manufacturing, technology, and research. While I had this timeframe and story arc in mind, the exhibition is the story of the collection, ultimately, so it’s not intended to be comprehensive.

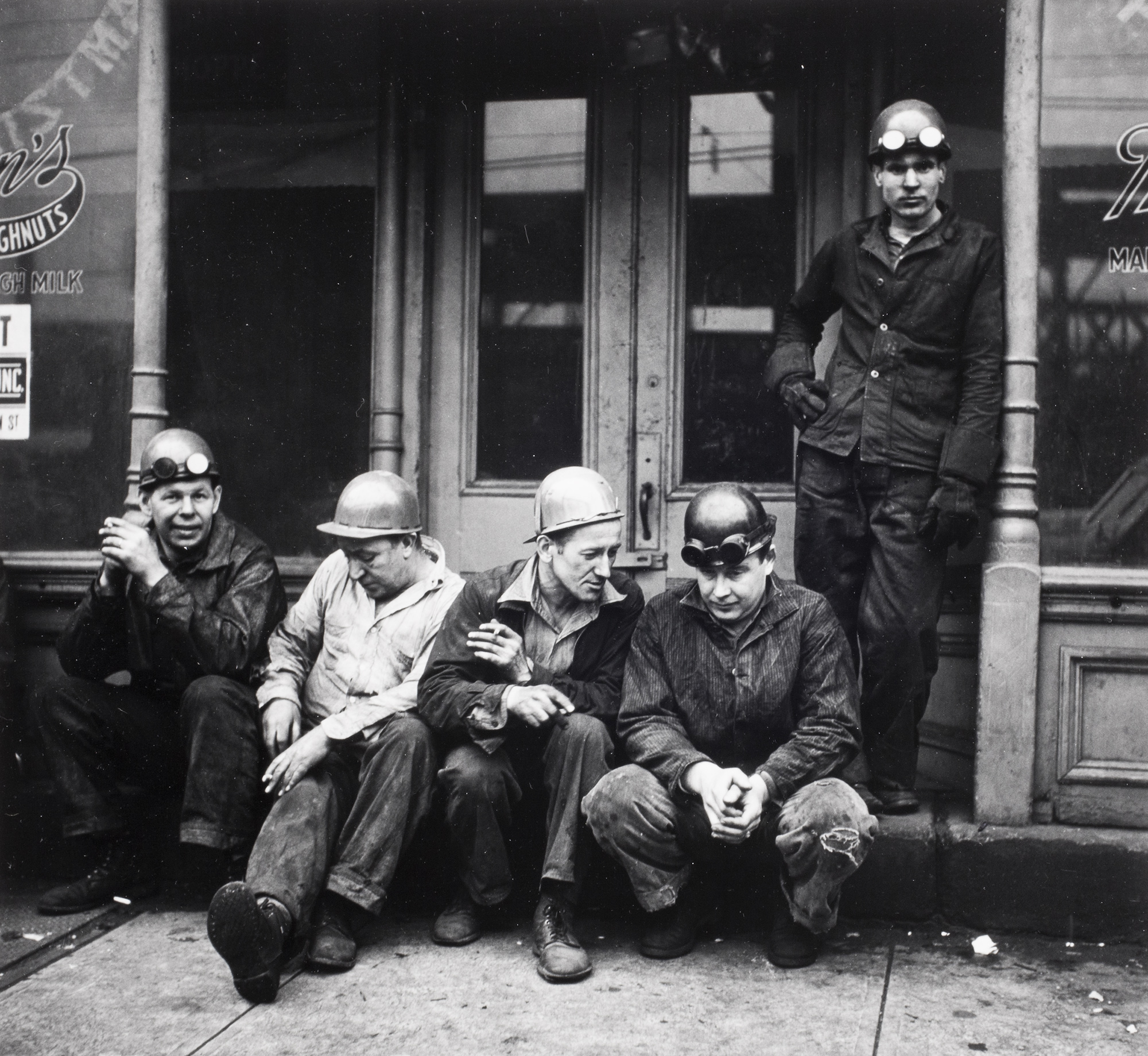

The exhibition begins in the 1940s and 1950s with a section titled, “Don’t Mourn, Organize,” which are reported to be the famous last words of the labor organizer Joe Hill. The section focuses on strike activity and labor in the media following World War II. I wanted to use the many press images in the ICP collection to demonstrate how the press directed the public to view strike activity. In one photograph, there are even arrows pointing to large rocks on the ground—emphasizing to viewers the unruliness of the strikers. Others are less didactic, though, like an image that draws a formal contrast between elegant women in skirt suits and the police officers trying to move them off the street in downtown San Francisco.

© John Broderick

The next section, “The Long 1960s,” surprised me in that it came to include multiple sections on the wall and in vitrines. I originally thought this era would just focus on the intersection of labor and the Civil Rights Movement, but in the archives I discovered a lot of photographs documenting Kennedy’s 1960 campaign and Paul Schuster’s work in Detroit and Pennsylvania. I liked including work by photographers who are known for other subjects, or including bodies of work that people may be familiar with, but in a new context, like Danny Lyon’s photographs of Lower Manhattan. For this period, there was also the opportunity to incorporate the ICP library collection, which has incredible holdings.

The 1970s section, “9 to 5,” named after the women’s labor advocacy organization, is about increasing presence of women in the workplace and women’s work as a political issue. ICP had acquired a photograph by Sophie Rivera, but there wasn’t much else, so I built the section around that through the addition of exhibition prints by Susan Meiselas, Freda Leinwand, and Bettye Lane. I think the lack of holdings in this area also says something about archiving and collecting, and how documentary work on the lives of women and by women photographers are often found in public and university archives and libraries. What I love about the section is that there is joy—you see the joy that people have in being able to do their work. Susan Meiselas introduced me to her work on the 1972 election, and that seemed to be another important dimension to add because of its place in the women’s rights movement.

Courtesy the International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos

© the artist and courtesy Contact Press Images

The 1980s section is called “The Everyday Life of the Servant Classes.” Ken Light has made a lot of work around workplace safety, an important issue which became a national concern with the formation of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in 1970. I wanted to show that work, and to incorporate books by Earl Dotter. The other part of the section draws from and builds on a series of photographs by Barbara Norfleet in the ICP collection, looking at different kinds of “servants”—public, private, and corporate.

As the exhibition moved into the 1990s and 2000s, I started with work by Joseph Rodriguez and Chien-Chi Chang and then built out from there. Accra Shepp’s work on Occupy Wall Street concludes the exhibition. Occupy was about a specific place, but it represented a national movement. That wider, national geography was important for me to engage for the exhibition. In photographs of Occupy, I saw so many echoes from the previous sections—some direct references, like the resemblance to the Poor People’s Campaign action in Washington. The work also reflects an intergenerational dialogue and action. During the installation, and finally seeing the work on the wall, I saw so many connections through time, and with other sections.

© the artist and courtesy Convoke NYC

Sloat: I found the Paul Fusco images of farm workers really impactful. Migrant labor’s an issue discussed in the contemporary news cycle, but despite the ubiquity of images on social media, news sources, and beyond, the stories of the laborers are not visible in a manner seen in the wider media during the sixties and seventies.

Best: One thing that is made clear in the books—La Causa: The California Grape Strike (1970) by Paul Fusco and From this Earth . . . of the Land of the Grape Strike (1969) by Jon Lewis, is how Cesar Chavez understood visibility and storytelling as tools for the cause. In both books, text and image complement each other. At times there is a performative aspect to it, an anticipation of the public gaze. The march from Delano to Sacramento was meant to be seen. And the wider American audience had already been primed for this. The day after Thanksgiving in 1960, Edward R. Murrow’s final documentary with CBS was Harvest of Shame, and it was widely seen. Its aesthetic was also very much in dialogue with the photography that many photographers knew—Dorothea Lange, for example.

Sloat: But the equation I see there is: “the photographer will record the protest. The protest will be publicized in the media.”

Best: Yes, but I think it’s more than that. It’s the awareness of protest as a visual act, and the ongoing evolution of that and how photography has responded. In the Ernest Withers photograph Sanitation Workers Assemble in Front of Clayborn Temple for a Solidarity March, Memphis, Tennessee, which I had never seen in the panoramic orientation of the print in the ICP collection, there is a man standing on the far left with his hand arm out, as if to instruct the protesters to stand in a line. It’s such a powerful detail.

Sloat: What happens when that equation is decentralized? At present we don’t have a singular media space and a clear audience. It feels very piecemeal. There’s a very different mechanism about how images can have an impact on policy, if at all.

Best: Right. In many ways, what emerges by the end of the exhibition is a challenge to that equation, and it’s not just because of the fracturing of media.

Sloat: What do you see as the role of photography as advocacy in our current world?

Best: I think the question for me is more, How does photograph approach advocacy? I don’t know that I have an idea about its role, which implies an identified outcome and impact. I’m interested in the aesthetic and storytelling approaches and how photography can interpret and record, and how that creates new forms of visuality and storytelling.

© the artist/Magnum Photos

© the artist

Sloat: I recall a similar interest in the mythology and documentation of the American experience in previous shows of yours, like The Time is Always Now, Devour the Land, and Documents of Risk and Faith. I’m curious how this show might fit in the kind of trajectory of how you think about photography and curate photography.

Best: Curatorially, what unites all of those projects is an exploration of the exhibition as a specific space in which to experience an argument, and as a means to connect stories across space and time. I’m interested in storytelling about American life, storytelling on the wall, in art. And then, of course, the ways in which the history of documentary photography and photojournalism run parallel. Curating from the collection is ultimately an opportunity to have a dialogue with other curators, and with an institutional history, and that opportunity was especially meaningful to me here.

American Job: 1940–2011 is on view at the International Center of Photography, New York, through May 5, 2025.