How Have Photography Curators Responded to Demands for Diversity?

After the social uprisings of 2020, museums from New Orleans to Toronto consider how collections and exhibitions might reframe art history—and better represent a changed cultural landscape.

Akasha Rabut, Candi, New Orleans, 2013

Courtesy the artist and the New Orleans Museum of Art

In summer 2020, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, along with many museums in between, were rightly criticized for their responses to the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others at the hands of police and to the protests sparked by those tragedies. Several institutions searched their collections and used artworks by Black artists, without permission, in social media posts. Some paired images with statements that did not directly condemn the killings or adequately acknowledge the pain in their communities

As Kimberly Drew, a writer and formerly the social media manager for the Metropolitan Museum, put it on Twitter, “I understand firsthand that finding something to say can be hard work. I am also saying that I would like to see you do that work.”

For decades, museums have embraced some artists whose work reveals and criticizes the inequities and violence that characterize North American societies. One lesson of 2020, however, was that too often the dialogue surrounding their work, especially conversations about race, had only haltingly led to meaningful institutional change. Major museums appeared ill prepared for the scale and the force of demands to decolonize their practices. How could museums create programming to welcome all audiences and, at the same time, increase diversity, equity, and inclusion among their staffs? More than a year later, what has been the result in the arts of a national reckoning? What steps have museums taken to catch up to a vastly changed social landscape?

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

The Art Institute of Chicago seems to have been among those better poised to respond. In 1994, the museum created a Leadership Advisory Committee composed of African American community members. The museum’s current director, James Rondeau, has accelerated similar efforts. When Matthew Witkovsky, head of the museum’s photography and media department, arrived in Chicago in 2009, he spent three-and-a-half years surveying the department’s photographic holdings and found them overwhelmingly composed of works from Western Europe and the United States, mostly by white men from about 1910 to 1960. Looking to expand that perspective, in 2012, he mounted Dawoud Bey: Harlem U.S.A. and arranged for twenty supporters, led by Leadership Advisory Committee members, to acquire for the museum vintage prints of the full series. Since then, Witkovsky and his colleagues have acquired more works from the artists they exhibit, including Deana Lawson and David Hartt; shown permanent collection pieces by lesser-known African American artists in exhibitions such as Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980 (2018); presented exhibitions on African artists, including Jo Ractliffe and Mimi Cherono Ng’ok; and hired specialists in African and Black photography.

Witkovsky makes a distinction between working with the collection, which proceeds from the art, and rethinking how the institution functions, which “is absolutely about redressing wrongs and thinking categorically.” These two “different sets of concerns can converge, and it’s best when they do converge so that all the audiences you want to reach, not least your own staff, see things that excite them.”

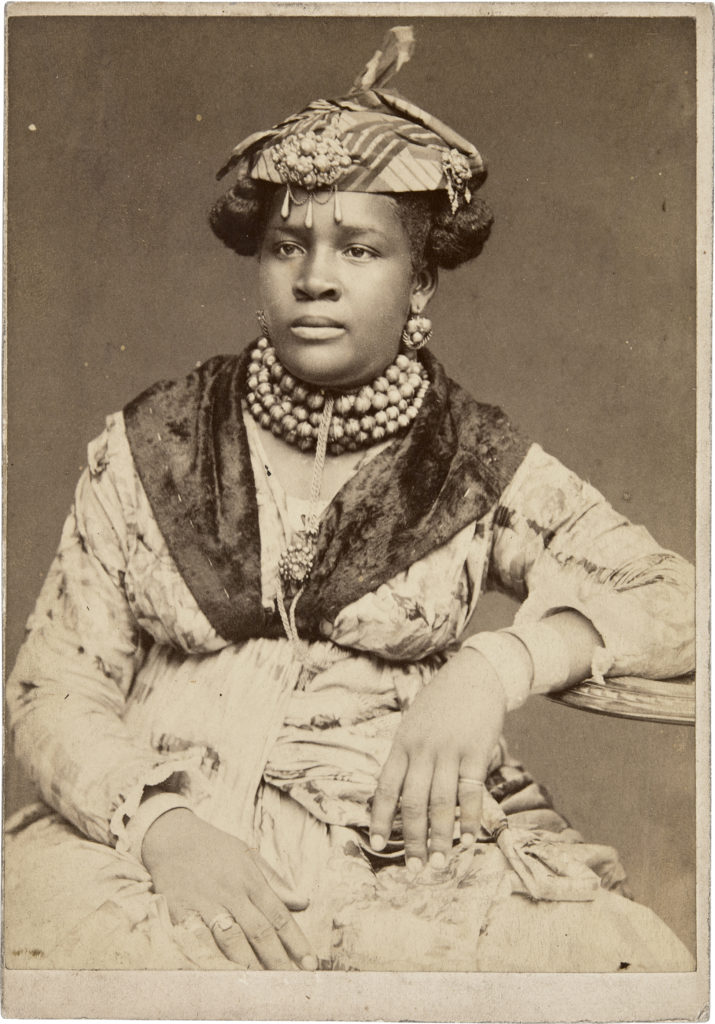

Montgomery Collection of Caribbean Photographs, Art Gallery of Ontario

Julie Crooks, who last fall was appointed to lead the department of arts of global Africa and the diaspora at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), had been a curator in the photography department since 2017. Accepting the museum’s job offer partly stemmed, she says, from a conversation with the AGO photography curator Sophie Hackett about “the importance of building a more diverse collection that reflects the character of Toronto.” Hackett had made major acquisitions of queer photography, along with a huge archive of Diane Arbus prints. Crooks’s most significant acquisition was of the Montgomery Collection of Caribbean Photographs, more than 3,500 historical images from thirty-four countries, which is billed as perhaps the largest compendium of Caribbean photography in a museum outside that region.

How could museums create programming to welcome all audiences? More than a year later, what has been the result in the arts of a national reckoning?

How Crooks and her colleagues acquired the Montgomery Collection is remarkable; it chimes with the Bey acquisition in Chicago and suggests a path forward. Rather than find one wealthy supporter to cover the cost, the AGO built a coalition of twenty-seven donors who contributed to the effort. Many are from Toronto’s Black and Caribbean communities; many are first-time donors to the museum. “It was important for us that there were feelings of ownership and legacy attached to this acquisition,” Crooks says. “Many of the supporters are adamant that these photographs won’t sit in a vault; they’re advocates for the collection being accessible.” The AGO’s 2021 exhibition Fragments of Epic Memory features selections from the Montgomery Collection.

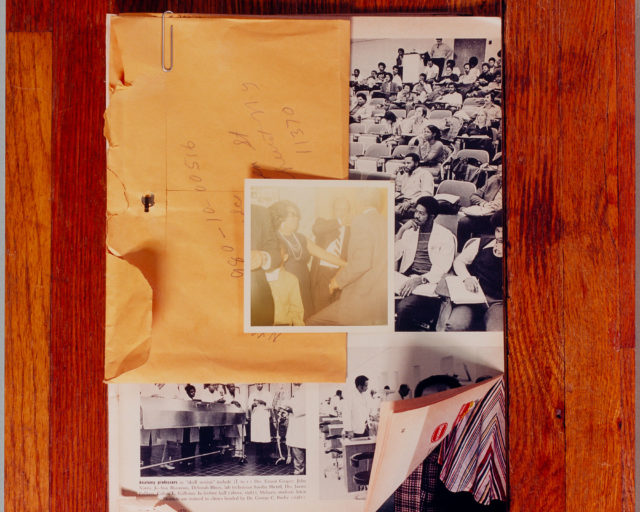

Courtesy the New Orleans Museum of Art

At the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA), the photography curator Russell Lord performed his own collection audit on his arrival in 2011 and found that the overwhelming bulk of the holdings, as in Chicago, was “canonical: white, American and European, male.” Lord knew he wanted to fill in the gaps. The department has recently acquired historical works from Japan and contemporary works by Chinese artists. It is building a Latin American collection. But Lord is also trying to find ways to suggest “diverse perspectives within the United States,” as with a 2021 collection-based exhibition of images by Ishimoto Yasuhiro, the American-born Japanese photographer whose feeling of being an outsider led him to immigrate to Tokyo in 1961.

In 2020, NOMA devoted all its available acquisition funds to buying art by BIPOC artists, more than half of whom call New Orleans home. Lord’s department acquired works by local artists Eric Waters and Akasha Rabut, among others. “It was important for the museum to make a visible commitment to the local community and to the diversity of its collection,” he says. “That was one result of a practice we’ve been moving toward over the past decade.”

Courtesy the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Conversations about diversity, equity, and inclusion have been particularly prominent around the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, in New York, since 2019, when Chaédria LaBouvier, a Black independent curator, accused the museum of racism in how it handled her exhibition on Jean-Michel Basquiat. After identifying omissions in the collection while organizing a major collection exhibition in 2010, Jennifer Blessing, senior curator of photography, has worked deliberately to make the museum more global, “especially in terms of African and African diaspora artists.” Blessing notes that while the 1996 exhibition In/Sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present, organized for the Guggenheim primarily by guest curators, including Okwui Enwezor, was a significant moment, that effort was “not fully recognized as part of our institutional history.”

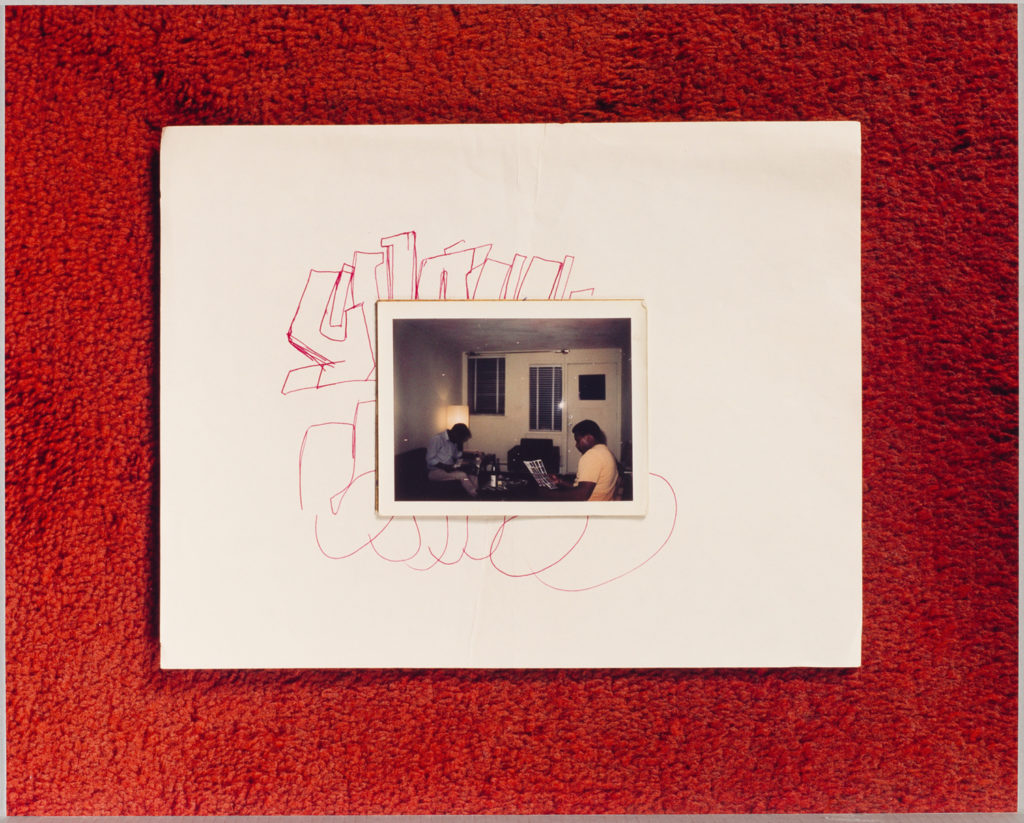

It took a 2001 gift from the Bohen Foundation of over two hundred works to bring photography by African artists, such as Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, into the Guggenheim’s collection. Blessing and her colleagues have supplemented this representation with purchases of photography by the South African artist Zanele Muholi, along with those of African American peers including Lorna Simpson, Hank Willis Thomas, and Leslie Hewitt. “When people talk about diversity and how we measure it, there is a tendency to focus on the number of artists or the number of objects,” Blessing says. “I think we should also consider how much money is being spent on artworks by artists of color.”

© Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Ashley James joined the Guggenheim as an associate curator in 2019 and immediately organized Off the Record (2021), an exhibition—with works by Simpson, Thomas, Hewitt, and others—about what’s left out of mainstream narratives. Like Crooks’s acquisition in Toronto, Off the Record created a gravitational force—the museum acquired the one piece in the show that was not previously in the collection: Tomashi Jackson’s Ecology of Fear (Gillum for Governor of Florida) (Freedom Riders bus bombed by KKK) (2020). According to James, “Off the Record has offered a bridge to people who can see their own visions reflected in the Guggenheim’s holdings.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx,” under the column “Backstory.”