Paolo Gasparini on How Photographs Can Help Us Learn to See

Gasparini spent his life documenting cities and people from Havana to Caracas. In a 2015 interview, he spoke about what it means to identify as a Latin American photographer.

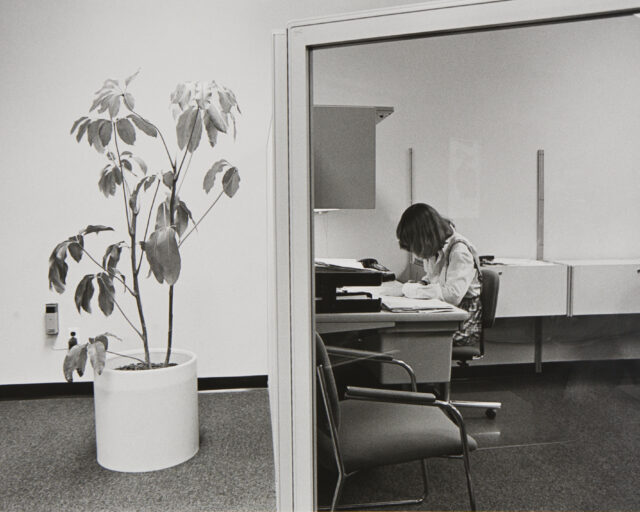

Paolo Gasparini, Leaving for the sugarcane harvest, Havana, 1964, from the series Cuba, ver para creer (Cuba, seeing is believing)

In spring 2024, nearly thirty years after he represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale, Paolo Gasparini returned to Venice to participate in the latest edition of the international exhibition, Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Adriano Pedrosa. Here, we revisit Gasparini’s conversation with Sagrario Berti in the magazine’s “Interview Issue,” originally published in fall 2015.

Although Paolo Gasparini was born in Italy, Venezuela is his adopted home. He has spent his life documenting the cities and people of Latin America, south of “the northern imperialist,” as he refers to the United States in the following interview. Born in 1934 in Gorizia, in Northeast Italy, he emigrated to Caracas in 1954 to join his mother and older brother. This was a time of oil fueled growth, prosperity, and urban expansion as well as inequality, poverty, and cramped living conditions in new housing complexes. Working alongside his architect brother Graziano, Gasparini sought to document both the transformation of the built environment and the city’s inhabitants.

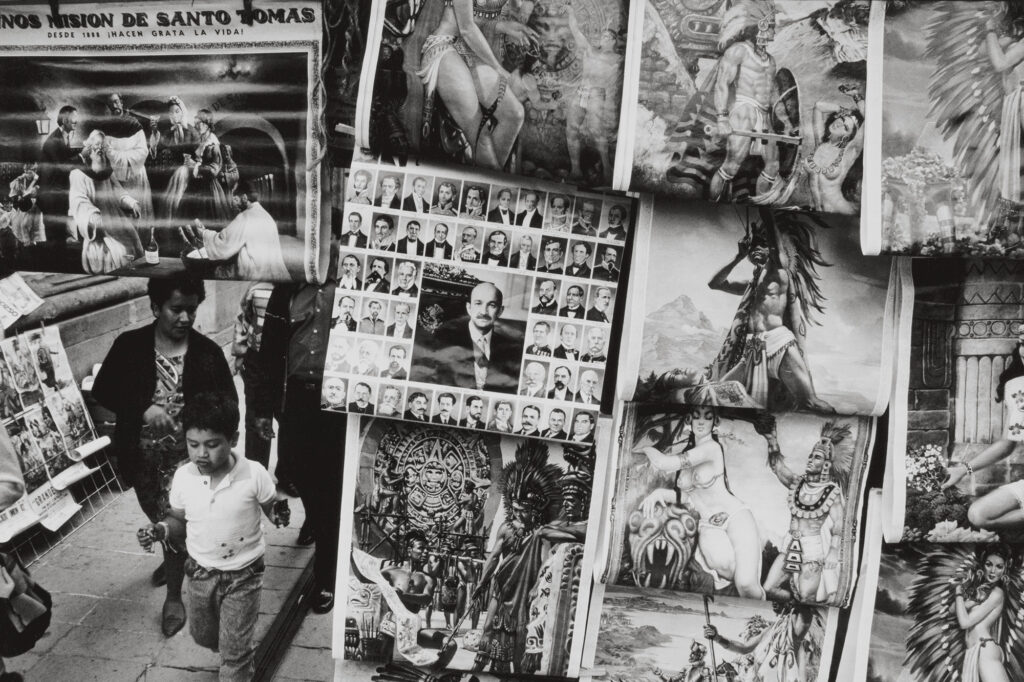

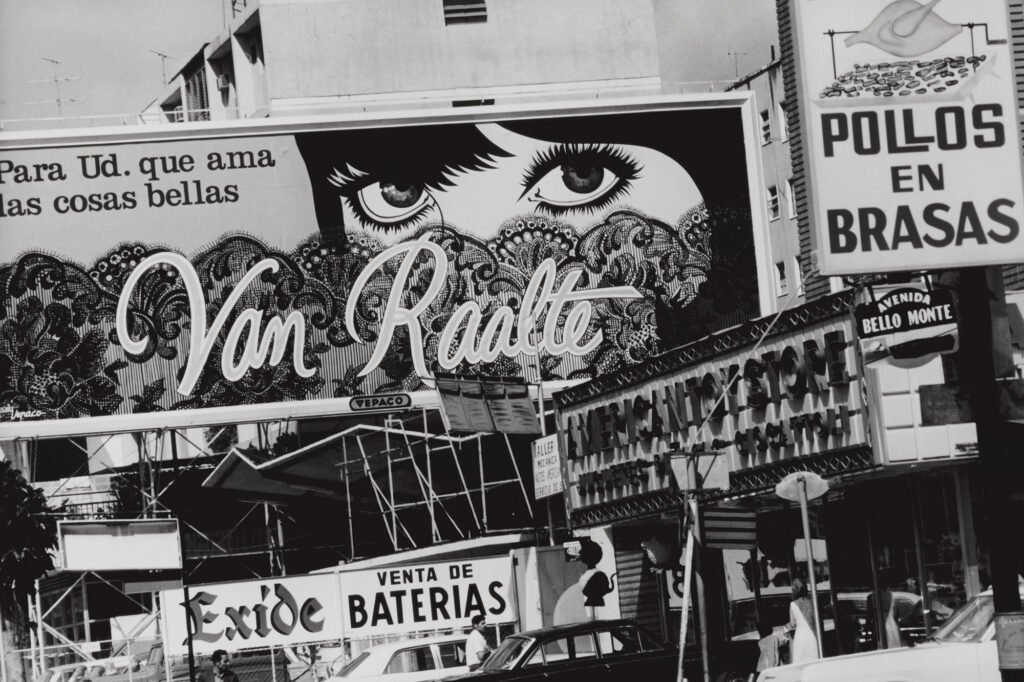

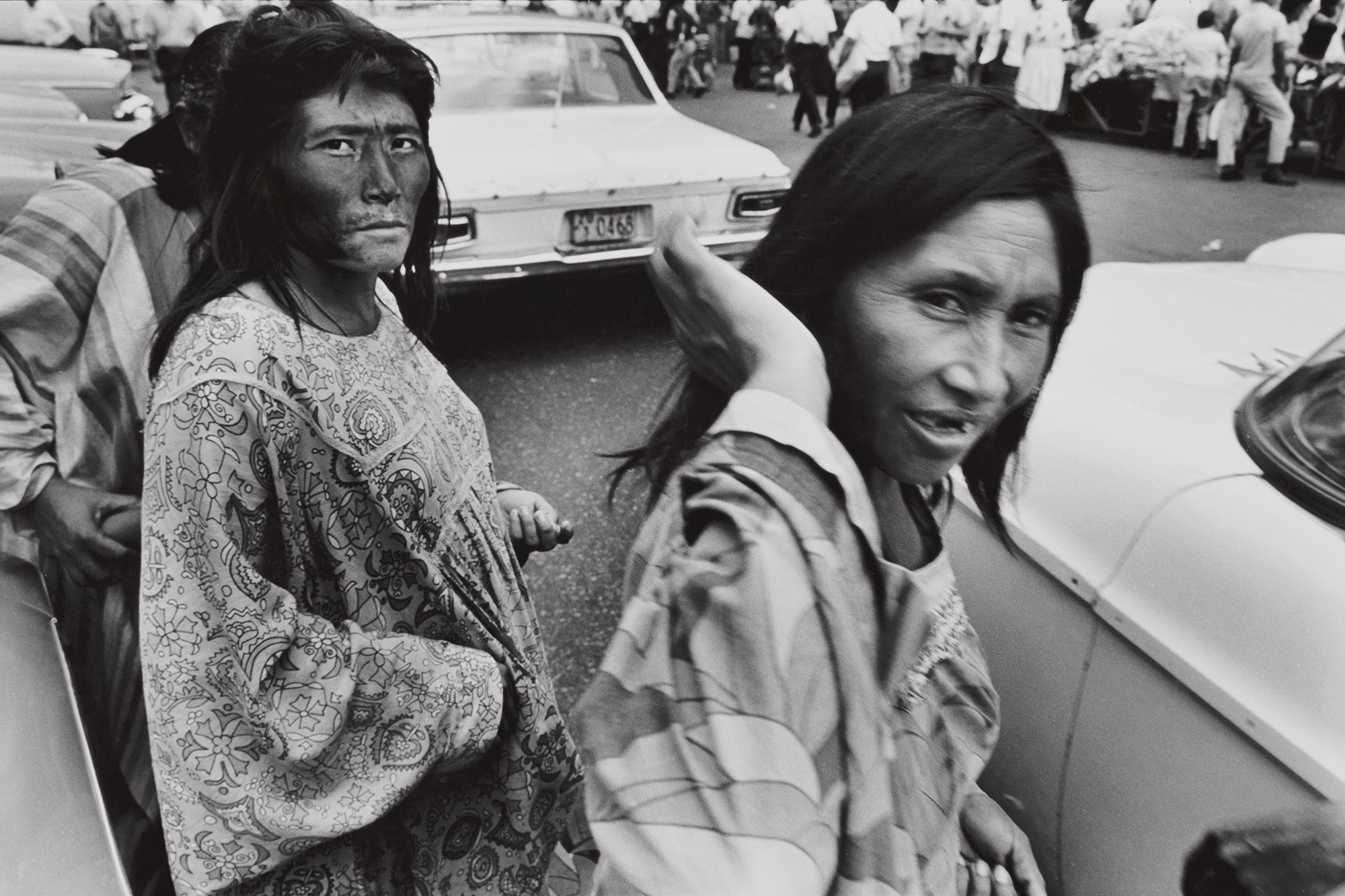

In 1961, impassioned by the Cuban Revolution, Gasparini traveled there and stayed for four years. Later, in the 1970s, he was commissioned by UNESCO to photograph urban centers from Mexico to Argentina, focusing on both architecture and the stark social inequality he witnessed. The project resulted in the photobook Para verte mejor, América Latina (The better to see you, Latin America, 1972), now considered a classic.

Gasparini has continued to make work, often reinterpreting his still photographs through the use of sound and elements of performance. In 1995, he represented Venezuela at the 46th Venice Biennale. For this interview, Sagrario Berti, a Venezuelan photography curator, researcher, and longtime friend, met with Gasparini at his home and studio in the Bello Monte neighborhood in Caracas. They spoke about his recent book Karakarakas, which features six decades’ worth of Caracas work; what it means to identify as a Latin American photographer; and why, for Gasparini, photographs should still be seen as a product of ideology.

Sagrario Berti: What led you to immigrate to Latin America and settle in Venezuela?

Paolo Gasparini: In order to avoid enlisting in the army, before turning twenty-one I moved to Caracas. My father and two brothers were already living there. My mother traveled constantly to Venezuela where Graziano, one of my brothers, was working as an architect and photographer. He was conducting research on popular, indigenous, and colonial architecture of Latin America.

Berti: Were you already taking photographs?

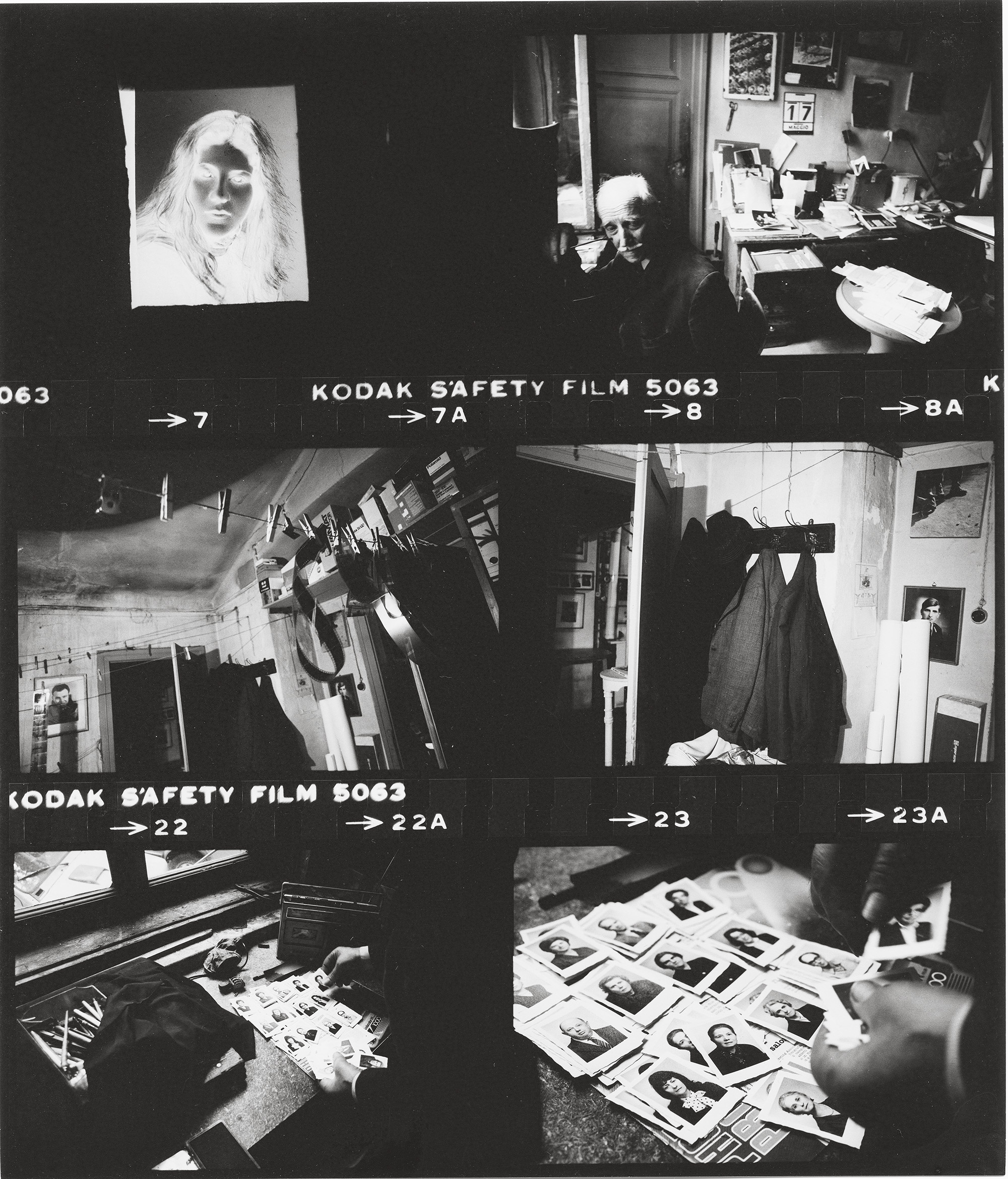

Gasparini: Yes. After one of my mother’s trips to Caracas, she came home with a Leica camera for me as a gift from Graziano, and at seventeen I began photographing. In Gorizia, Italy, my girlfriend Franca Donda and I frequented a photography studio. That’s where we learned developing and copying techniques. I also took part in the exhibitions organized by Gorizia’s photo-club, where I showed photographs of fishermen, peasants, and circus workers.

Berti: And in Caracas?

Gasparini: Having only been in Caracas for eight days, thanks to Graziano’s architect friends, I began photographing the buildings of Carlos Raúl Villanueva, Venezuela’s great modernist architect: the Central University of Venezuela and the construction of the 23 de Enero [January 23] public housing blocks. I settled into a rich cultural world full of writers, philosophers, critics, and thinkers from the magazine Cruz del Sur (1951–61), a publication run by Violeta and Alfredo Roffé that linked cultural issues with societal problems and served as a focal point for leftist intellectuals who opposed the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952–58). I worked for Villanueva and for architects like Pedro Neuberger, Dirk Bornhorst, and Jorge Romero Gutiérrez on El Helicoide, a proposed shopping mall and industrial exposition center in Caracas built on a rock of gigantic proportions that was never finished. Now it’s a prison.

Berti: You alternated between being an architectural photographer and documenting various neighborhoods. You also traveled around the interior of the country. Which work from this period do you consider most important?

Gasparini: My architectural work, without a doubt. Remember, this period marked the beginnings of publicity and advertising in Venezuela. I had offers to work in publicity that were much better paid, but I turned them all down because I was not, and am still not, interested in advertising photography used to sell products. I traveled either by myself or with Graziano. We went all over the Paraguaná. Peninsula, an arid territory, between 1954 and 1960. We traveled from Los Castillos on the Orinoco River—in the eastern part of Venezuela—and ended up enjoying ourselves and admiring the white houses of the Falcón State in the west. Then we moved onward to the market of Los Filúos in the Guajira Peninsula, on the border of Colombia, and crossed the Andes. Over the course of these travels I made two photo-essays: Las Salinas de Margarita (The salt mines/lakes of Margarita) and Bobare, el pueblo más miserable del Estado Lara (Bobare, the most miserable town in the State of Lara). Both were published in Cruz del Sur. I photographed Bobare under Paul Strand’s documentary influence. Franca, who was living in Paris at the time, contacted Strand—who was self-exiled in Paris, fleeing from McCarthyism in the U.S.—and showed him the work that had been published in the magazine, as well as other photographs that I had taken in Venezuela. Strand brutally criticized Bobare. At one point he told me, “I had to look at it under a yellow light in order to soften the unpleasant yellow hue of the print.” But he liked the other photographs. [Gasparini and Strand met later, in Orgeval, France, in 1956.]

Berti: Aside from Strand, what were your influences?

Gasparini: When I was eleven, I saw the horrors of World War II: photographs of bodies that had been mutilated, hung, and shot. The photographs belonged to a Yugoslav partisan and guerrilla fighter. This was my first experience with photography and it caused a deep impression.

My visual imagination was also fed by magazine photography and film. During the postwar period I went to the Venice Film Festival; at the time, in the United States Information Agency offices, the American Army was projecting films in Gorizia and Trieste. In Venice I saw The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936); The River (1938), which was produced by the Farm Security Administration; [Robert] Flaherty’s film Nanook of the North (1922); The Photographer (1948), a documentary on Edward Weston; and the first images from the concentration camps. I saw films that hadn’t been screened in Italy because of the war, Gone with the Wind (1939) and Que Viva Mexico! (1930), for example, and, of course, the Italian neorealism of [Cesare] Zavattini, [Roberto] Rossellini, and [Vittorio] De Sica.

I became acquainted with the “American way of life” through magazines like Collier’s, Life, and Picture Post. I became enraptured by photography in the films of Paul Strand, such as Redes (1936), and I was especially drawn to the documentary photography, or rather the “social realism,” of his book La France de Profil [with Claude Roy, 1952].

So the basis of my imagination was the documentary propaganda disseminated by the United States army. I left Europe for South America with the war photographs that I’d seen, and with my head full of images of America—hence my constant need to represent both worlds in my photographic practice.

Berti: You lived in Cuba between 1961 and 1965, after the revolution. You photographed with Alejo Carpentier, the renowned Cuban writer, and published the book La ciudad de las columnas (The city of columns, 1970). What drew you to Cuba?

Gasparini: On the one hand, there was an interest in modernity, beauty, folklore, and the authenticity of American life—in magical realism. In 1958, on the other hand, the Cuban Revolution had exploded as a response to the deep social problems that existed in Cuba and the rest of Latin America. The Cuban architect Ricardo Porro and Alejo Carpentier—both exiled in Venezuela—invited me to visit Cuba. I went with Franca; we were married by then. We intended to stay six months but the trip was extended to four and a half years. Carpentier wanted to write a book about Havana, an archive of baroque Cuban architecture—that’s what became La ciudad de las columnas. He liked my “walking” work, he said, because I passed through all of the city streets, registering the stained-glass windows, hallways, and gates. I also befriended many of the fervent supporters of the first revolutionary wave.

Berti: Following the parties celebrating the Cuban Revolution, you shifted the content and style of your photographs, focusing on people living in poverty.

Gasparini: Yes, the speed of the social and cultural events in Cuba made me change my camera. I switched from medium- and large-format reflex cameras (which I used thanks to Strand) to a versatile 35mm, which obviously changed my way of seeing and capturing reality with tremendous speed. I became part of the artistic and intellectual circles, which included photographers, filmmakers, and architects such as Santiago Álvarez, Alberto Korda, and Iván Espín. In Havana I also met Cartier-Bresson, René Burri, Chris Marker, and Italo Calvino, all formidable intellectuals. This amplified my desire to expand the discourse of the Cuban Revolution throughout all of Latin America.

Berti: How did your Cuban themes differ from those in your other Latin American work?

Gasparini: In Cuba I documented the celebration, euphoria, triumph, and hope following the revolution. In the rest of Latin America, I documented social contradictions.

Berti: When did you begin to expand your travel around Latin America?

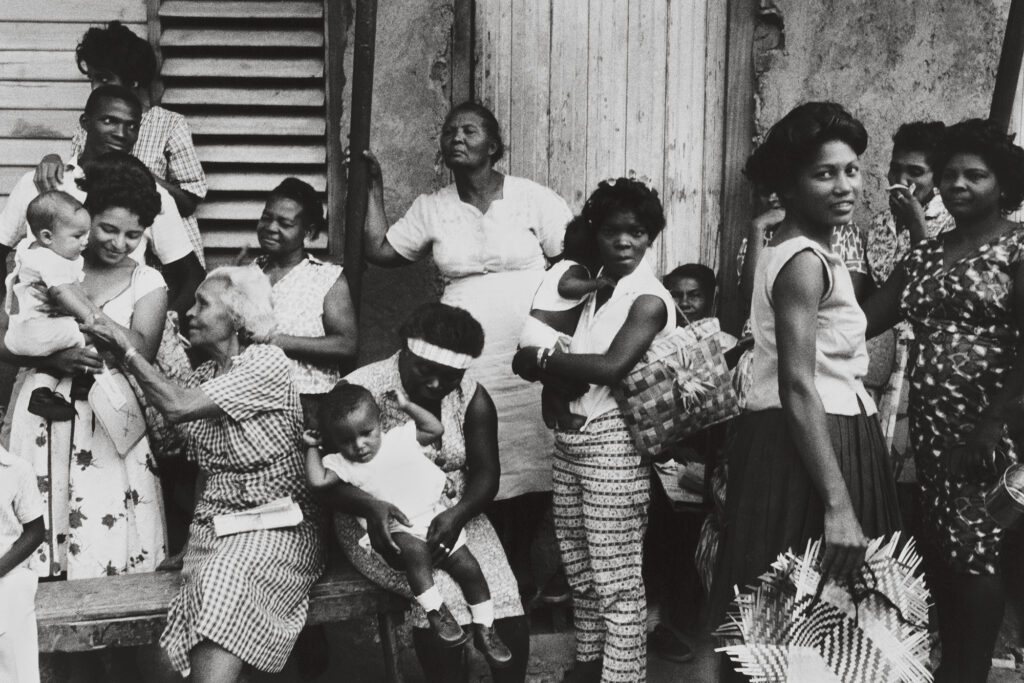

Gasparini: In 1970, UNESCO hired me to photograph pre-Columbian, colonial, and contemporary edifices. I focused on the urban building projects being erected from Mexico to the Pampas, from Brasília to Machu Picchu, designed by great modernist architects. I insisted on photographing the lives of marginalized individuals, of those who have nothing, and the huge differences that coexist beside and around these huge building projects.

Berti: In addition to the book Panorama of Latin American Architecture (1977), you published the book of photographs Para verte mejor, América Latina. How did this project materialize and where did the title come from?

Gasparini: It came from an eagerness to document Cuba once again. Edmundo Desnoes wrote the text and Humberto Peña designed the book. The title paraphrases [Charles] Perrault’s story “Little Red Riding Hood” (1967).

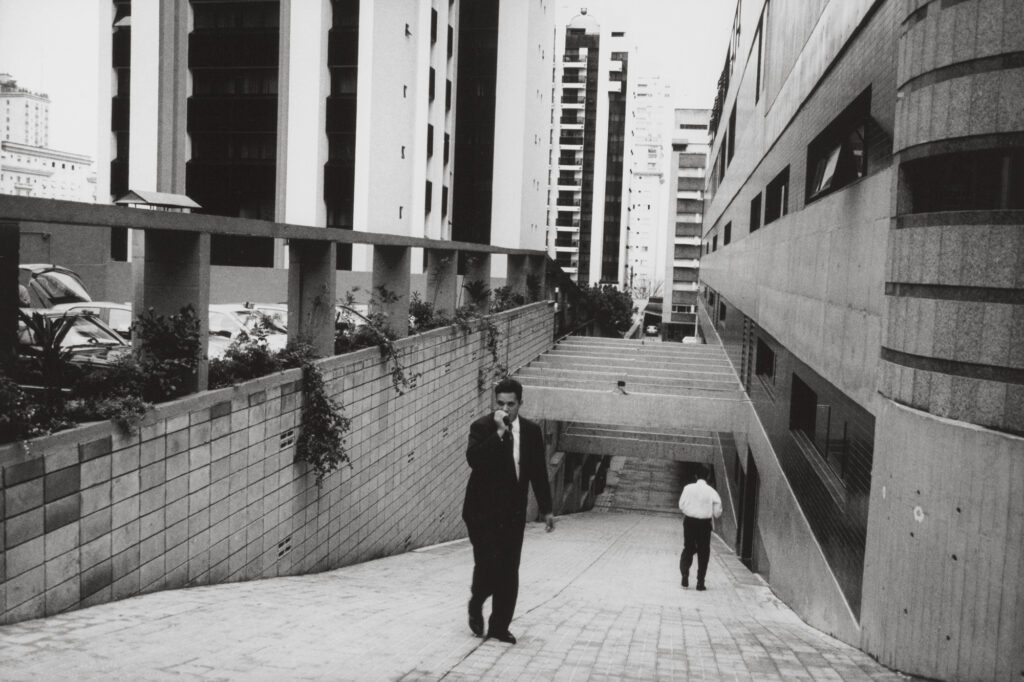

Berti: Tell me about Retromundo (Retroworld, 1986), your second book, which was about the representation of two worlds, Europe and Latin America. Here you juxtapose two ways of life: that of the inhabitants of Paris, New York, and Rome, and that of citizens in São Paulo, Mexico City, and Lima.

Gasparini: As I told you earlier, I left Europe with images of America. Later on, I returned to the first world carrying images of the Latin American reality. That’s where Retromundo came from—a book of photographs that doesn’t confront realities but rather tries to serve as evidence for what’s occurring on both continents.

Berti: And El suplicante (The supplicant, 2010)? Where did you get the idea of structuring a book according to your long travels through Mexico?

Gasparini: El suplicante was another adventure. I was invited to develop a project based on the urban culture of Mexico City. I took a photographic tour from the border of the northern imperialist to Subcomandante Marcos’s land of Chiapas.

Berti: And your most recent book, Karakarakas [wordplay on Caracas that incorporates the “ka” sound from the words Kodak and Kafka] (2014), takes the form of a political manifesto about the city.

Gasparini: That book brings together photographs taken in Caracas between 1954 and 2014. I put together these photographs with il senno di poi, “the wisdom of hindsight.” I combined images, connecting them with different themes, places, and dates, in an attempt to organize a new discourse that—by way of architecture and certain aspects of daily urban life—would offer a reinterpretation of Caracas’s past and evolution, representing its social, political, and cultural contradictions. As in the previous books, I worked with a great team. The book managed to give significant shape to a politically urgent discourse on the circumstances Venezuela currently endures, from the incongruences of the Bolivarian Revolution to the so-called socialism of the twenty-first century. I also tried to reflect, through architecture, on daily city life in this country that’s so wealthy with oil and yet so poor—a failure of modernity—and on the empty commitments of the governments preceding Chávez.

Berti: You also include images of the last sixteen years, which comprise the Chávez and post- Chávez years (1999–present). Looking at Karakarakas, it seems that the situation has not advanced. We see no changes, and the misery and poverty continue.

Gasparini: Chávez was the product, precisely, of a nonworking democracy. He wanted to put an end to the bourgeois government and built a populist state that ended up dividing the people. The result has been the destruction of modern society, economic ruin, and the collapse of basic services: health care, education, work, among others. No one knows—nor can define—the economic, political, and social chaos we’re suffering.

Berti: In your Fotomurales (Photo-murals), which you began in the ’90s and are still working on, and in the series Epifanías (Epiphanies, 1980s–90s), you use audiovisual narratives. Why use an audiovisual component in a photography book project?

Gasparini: This allows me to incorporate spoken or written texts—poetry, music, sound, and imagery. Above all, it allows me to add a temporal shift. For me, audiovisual is the most complex and all-encompassing medium. The form helps deepen what I want to express. There I find what the photograph on its own doesn’t provide—with its claim to replace the disorder of the world with the balanced order of the composition.

Berti: Since the 1980s you’ve been presenting audiovisuals together with slide-show projections, synchronizing three carousels of slides in a cinematic way. You orchestrated the projection in museums as well, as a sort of in situ performance.

Gasparini: The performance is important because, as the author of the project, I am present. The projection allows me to establish a dialogue with the public. Before projecting the piece, I can insert or extract images and organize a loose discourse, one that’s mutable and changeable, different with every projection.

Berti: You have often framed writing in your photographs, be it publicity slogans or graffiti. Do you feel that the image is not significant in and of itself?

Gasparini: The image on its own nailed to a wall doesn’t interest me. My interest has always been to edit images in the same way as words or discourse. From a fleeting image I like to develop visual phrases.

Berti: In the series Fotomurales, in some of the audiovisuals (early 2000s), you appropriated the revolutionary iconography of the continent, depicting Che or Tina Modotti; you uplift heroes who were dedicated to the Cuban dictatorship, as in Che’s case. Is this a way of remembering or refreshing a political position?

Gasparini: What you’re asking corresponds with a specific moment and context in recent Latin American history. In the ’60s and ’70s, there wasn’t a single place in South America that hadn’t been invaded by a political or advertising message, to the point where Coca-Cola and Che both became hypercontaminated icons in Latin America’s cultural memory.

Berti: In Modotti’s case it seems more like a romantic relationship.

Gasparini: Tina is special. She was born in Udine, a city close to Gorizia, my native city. When I was very young, Strand spoke to me of her, describing her as a great heroine of the revolution and an extraordinary photographer. In Mexico, I was a friend of [Manuel] Álvarez Bravo’s, who studied, worked, and helped Tina with her Mexican ordeal, so full of betrayals. Edward Weston’s journals speak of Tina, and for years his journals were by my bedside. In addition, Tina was beautiful and her photography was beautiful. Tina is another love in the journey of my life.

Berti: You developed your photography practice in close collaboration with the women you shared your life with.

Gasparini: I’ve been lucky. With the women I’ve loved I’ve had relationships filled with complicity and mutual interests. They were all intelligent, passionate, curious about photography, and shared my concern for social equality. Franca was a great partner; she helped me with my lab work. Duda Ferrari, an Italian architect, complemented my architecture work and designed several political publications in Caracas in the 1970s. With María Teresa Boulton I began a project of promoting photography as art in Venezuela, through the Fototeca gallery (1977–82), later the Venezuelan Council for Photography. Finally, with Marianela Figarella, an intelligent and passionate researcher, I shared ideas about photography as art and cultural product.

Berti: You still take pictures. Why?

Gasparini: In the end, after so many journeys, I believe there are some images that “bite,” or pierce you, as Barthes notes. I think photographs can help us learn how to look. How to think about and resist this world that’s consecrated to the grandiloquence of symbols that propagate lies and that, more and more, reduce and undervalue life.

Berti: How do you view the relationship between politics and photography?

Gasparini: Whether the formalists and Conceptualists like it or not, the image—the photograph—is a product of ideology. What is captured is in the mind of the person who triggers the shutter. Photography is the result of a thought process; it’s a serious subject. It’s not a click made with, say, a smartphone for uploading photographs to Instagram or Facebook.

Berti: Why take a political stance?

Gasparini: As Georges Didi-Huberman, a popular philosopher among the young Venezuelan Conceptual artists, says, “In order to know, you have to take a position. To take a position is to want, is to demand something, is to situate oneself in the present and aspire to a future.”

Berti: What do you think about being considered a Latin American photographer?

Gasparini: I’m eighty-one years old. I’ve lived for sixty years in Latin America and twenty in Italy. I’ve lived between two worlds and I travel frequently. Obviously I consider myself a Latin American photographer in the sense that my work is connected to the social and cultural events of the continent.

All photographs © and courtesy Paolo Gasparini

Berti: Is there such a thing as Latin American photography?

Gasparini: If we locate photographic practice in a given territory, evidently Latin American photography exists, in the same way people speak of North American or Japanese photography. Photography has a history here: The second half of the nineteenth century saw the rise of travel photography and its stubborn depiction of the “other.” The first decade of the twentieth century included Agustín Casasola’s extensive and unprecedented coverage of the Mexican Revolution. The Cuban Revolution expanded the drive to photograph every corner of Latin America. During the Cold War, the medium was used by those we now call the “Conceptualists of the South” as a tool for dissent against totalitarian regimes, such as Pinochet’s in Chile.

Recently, Alexis Fabry curated the exhibition América Latina: Photographs, 1960–2013 (2013) at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, and also organized Urbes Mutantes (Mutated metropolises, 2013–14), in Bogotá and New York; these were extraordinary exhibitions that covered a wide repertoire of photographs made in Latin America. Currently, many photographers work in the region, documenting diverse local realities, and they generate proposals that are comparable to those of photographers on other continents.

Berti: You’ve spent more than sixty years taking photographs. Do you have an opinion about contemporary photography?

Gasparini: Paul Strand, my teacher and friend, fought all his life for socialist ideals and for photography to be accepted in museums and purchased for its rightful commercial value. Now, in Latin America and in the rest of the world, socialism is dead or confined to museums. Photographs are sold at art fairs, veritable art supermarkets. Strand’s photographs sell for thousands at art auctions: they’ve gone for more than a hundred thousand dollars! It has all come to pass, cara Sagrario.

Translated from the Spanish by Elianna Kan and Paula Kupfer. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue.”