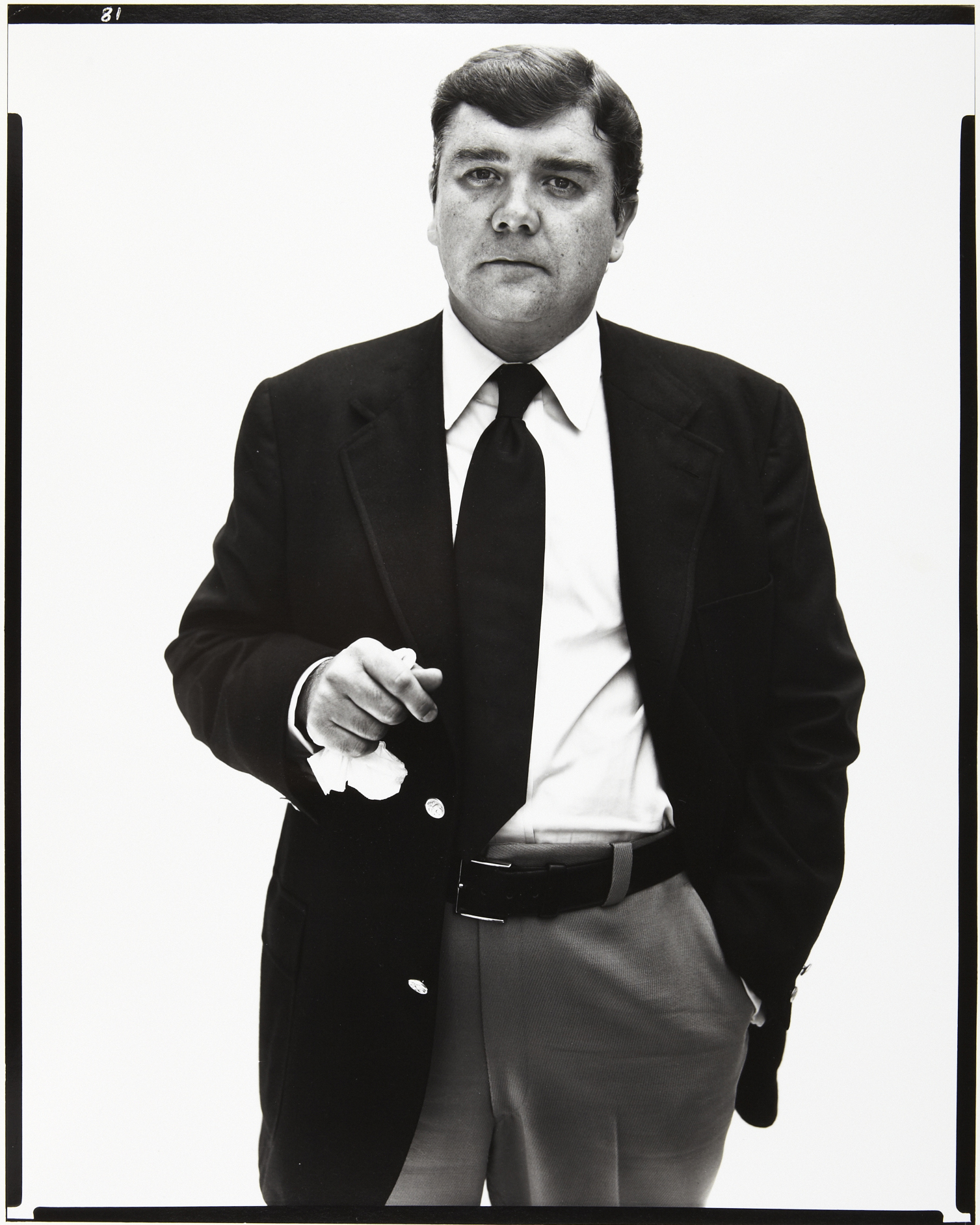

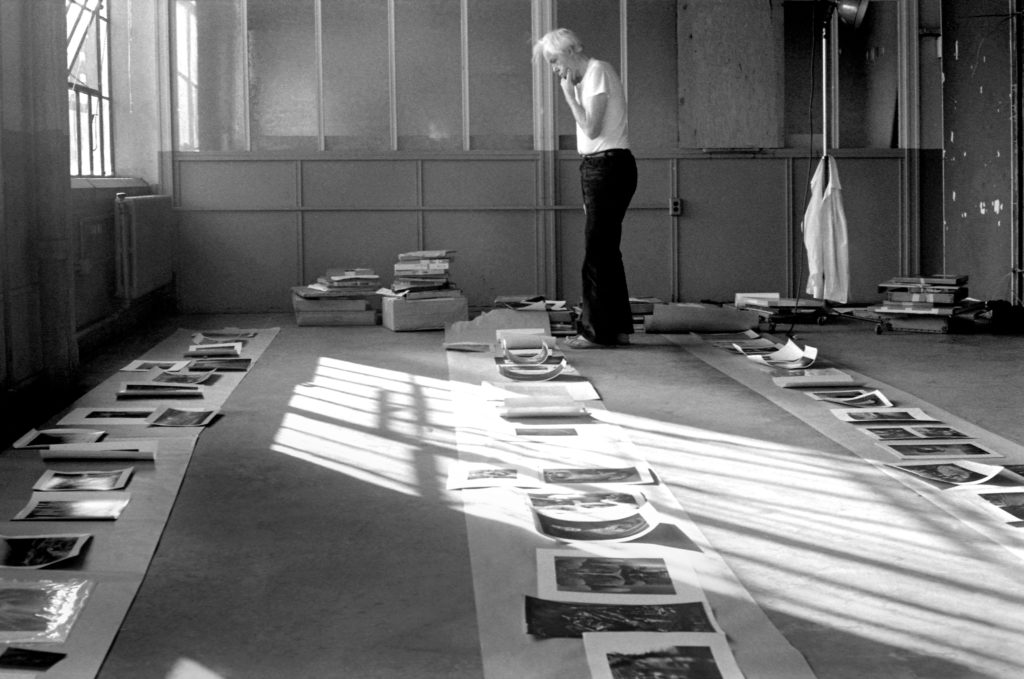

Richard Avedon, Peter Bunnell, March 30, 1977. Gelatin-silver print.

Courtesy Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of the artist © Richard Avedon Foundation (x1981-33)

It is with deep sadness that Aperture learned of Peter C. Bunnell’s passing on September 20, 2021. An eminent photography historian and curator, Bunnell (born in 1937) was also a mentor and friend to scores of individuals engaged with the medium of photography today, including me. Curiously, our professional paths have followed inverse trajectories—his from Aperture to New York’s Museum of Modern Art to Princeton University; mine from Princeton to MoMA to Aperture—but at each step, his example served as a guiding light.

I met Professor Bunnell in 1992, when I took his history of photography course as an undergraduate at Princeton. He animated the full sweep of this history with insight and anecdote. Edward Weston wasn’t simply a legendary name from the past; he was someone with whom Bunnell had corresponded in 1956. As I recall the story, my esteemed professor was a sophomore at the Rochester Institute of Technology, studying with Minor White, and he wrote a letter to Weston requesting two prints and enclosing a check for $30. Weston wrote back, enclosing two prints! I also vividly remember encountering a work by Uta Barth in a seminar my senior year, which Bunnell had just acquired for the university’s collection. Bunnell’s attentiveness to new achievements and his passion for Barth’s distinctive approach—removing the ostensible subject of her photograph to draw attention to the surrounding (often blurred) background—was an inspiration to all of us fortunate enough to be in his orbit.

In 1972, Bunnell had been named the inaugural David Hunter McAlpin Professor of the History of Photography and Modern Art at Princeton, the nation’s first endowed professorship of the history of photography. Previously, he was a curator in the Department of Photography at MoMA, and it was there that I headed (as an intern) after graduation. Eventually I, too, became a MoMA photography curator, ever-conscious of several landmark exhibitions Bunnell had organized during his tenure there. The most radical of these, still today, is Photography into Sculpture (1970), but he also brought a fresh perspective to historical figures such as Barbara Morgan (a founder of Aperture) and Clarence H. White, whom he described as being “interested in revealing how things are, rather than showing things as they are.” To my mind, Pictorialism was so unfashionable that this embrace of one of its leading figures was itself a radical gesture.

Before MoMA, Bunnell had spent a decade working closely with Minor White at Aperture, nurturing the magazine through uncertain times. The interview that follows, with Diana C. Stoll, was originally published in Aperture Magazine Anthology: The Minor White Years, 1952–1976 (Aperture, 2012), a treasured resource for anyone interested in the field and full of Bunnellian flair. Peter C. Bunnell’s achievements as a scholar and writer will continue to instruct and inspire—he will be missed.

— Sarah Meister, Executive Director, Aperture Foundation

Seated left to right: unidentified woman, Victor Babin (musician), Aline Porter, Will Connell, Wayne Miller, Ferenc Berko, Vitya Vronsky (musician), Eliot Porter, Nancy Newhall, unidentified man, Beaumont Newhall, Minor White

Image courtesy Norma and Laura Bishop, and The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

Diana C. Stoll: From today’s perspective, the world of photography in 1952 seems so appealingly finite and manageable. Who was reading Aperture in the beginning? For whom was it intended?

Peter C. Bunnell: In a way, Aperture was for a small niche. It was intended for those who were committed to serious photography.

After World War II, photography as an art was confronted with the new status of photojournalism—the residue of 1930s documentary work—as well as the rise of advertising and magazine photography. Aperture was essentially driven by the idea that there must be some way to reposition a kind of serious photography, and that notion drew together the group of people who founded the magazine.

Aperture grew out of a 1951 conference on photography that was held at the Aspen Institute. A number of people had been invited to the conference who could address the reality of the field. If you look at the seminar titles, you get an idea of what some of the concerns were: “Evolution of a New Photographic Vision,” “Photography and Civilization,” “Picture Language and the Magazine,” “Photography in Advertising and Promotion,” “Photography and Painting,” “Objectives for Photography,” “Creative Directions in Color Photography.”

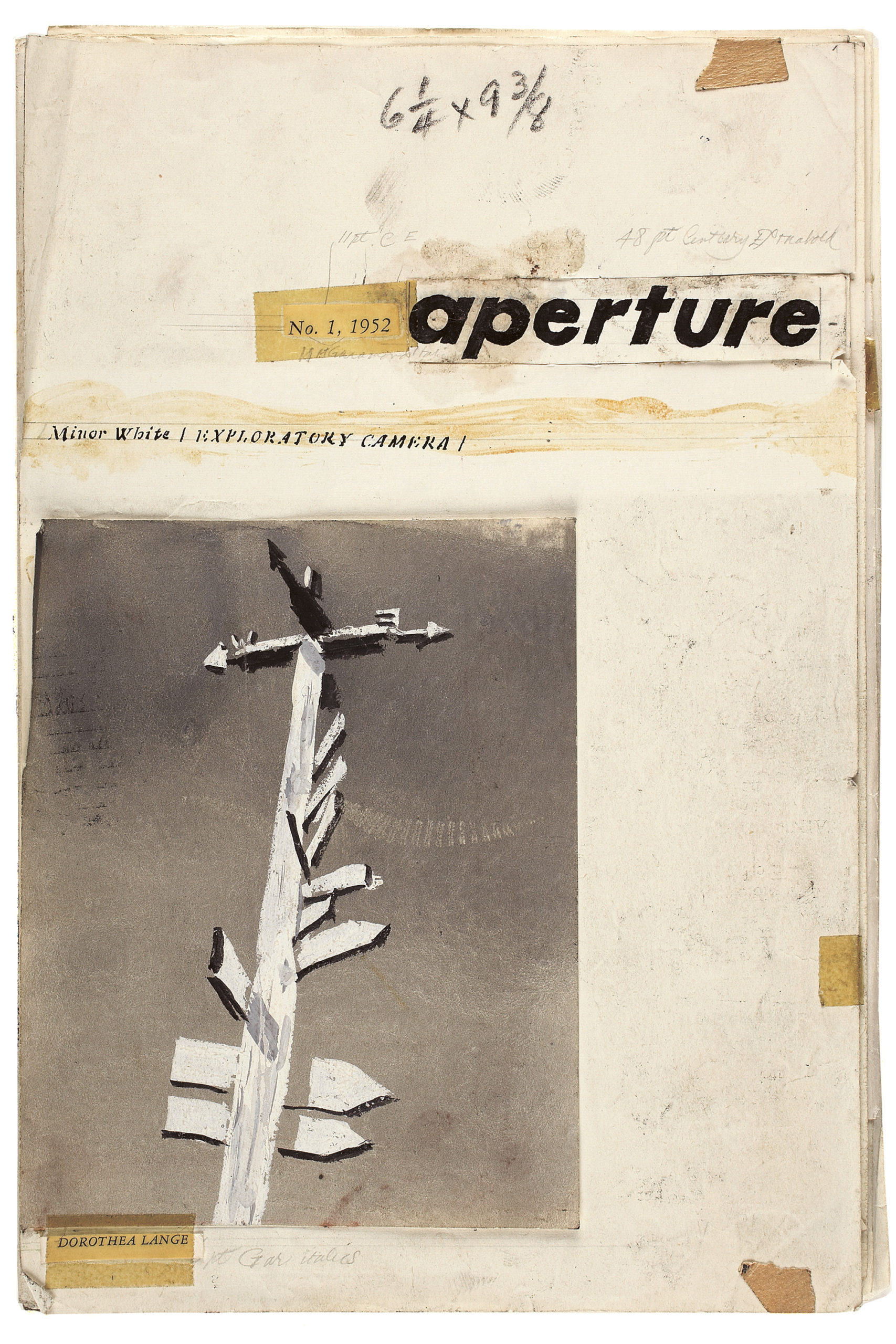

There was a subgroup at the gathering, which included Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, Minor White, Frederick Sommer, Ansel Adams, and Dorothea Lange. Aperture literally started with attendees of that Aspen conference, who after the meeting received letters saying: “This magazine has now been born. Here we go.”

To get it moving, Ansel reached out to people he knew, people like photography patron David McAlpin, for instance, and writer and editor Dorothy Norman, who had been Stieglitz’s sponsor. And there were other bits of help along the way. Jacob Deschin announced the first issue of the magazine in the New York Times [March 16, 1952] and gave the address for subscriptions. So progressively, mostly by word of mouth, it began to reach people. Including faculty and students of universities—like me.

Stoll: What led you to photography?

Bunnell: When I was young, my initial idea was to be a fashion or magazine-illustration photographer. I thought that’s where the glamour was. My father, who was a mechanical engineer, wanted me to be an engineer, but I didn’t want to do that. As a teenager, I bought my first camera, an Argus C3 (which I later learned was the first camera Minor bought, in 1937). I learned how to develop and print, and I realized that I could make money photographing couples at dances and things like that. So I set up a little makeshift studio, and started selling 8-by-10 prints—and it kept getting me further and further from having to be an engineer.

I went to the Rochester Institute of Technology—R.I.T.—to study. R.I.T. was one of the few places to go for photography in 1954 or 1955; it had just begun a four-year program for photography. Minor had been brought in as added faculty when they expanded from a two-year program. He was first hired to teach photojournalism.

Stoll: But he wasn’t a photojournalist.

Bunnell: Right, he was not a photojournalist, but the idea was: if you know anything about photography, you can do it. You just put it in Life magazine! R.I.T.’s photography program was run like a trade school. For the first two years you studied physics, sensitometry, photochemistry; then maybe you could take a few pictures, but not many, because you were always busy in a lab someplace.

Then, all of a sudden, there was Minor. He taught a sophomore course (which derived from his curriculum at the California School of Fine Arts [C.S.F.A.], where he had taught previously) called “Visual Communication.” It was a whole new approach. We cut out pictures and glued them together to make multiple images. We did everything in that class—including learning how to “read” photographs. It was very eye opening.

Before the Thanksgiving break of 1956, Minor said to the students: “I’m having people over on Saturday evening; those of you who are not going home are all welcome.” I wasn’t going home (remember, I was trying to avoid my father), so a friend and I decided to go to Minor’s apartment. He had cooked a turkey—but I think only for about an hour, so it was practically bleeding! There were some other students, and Walter Chappell was there . . . and then in walked Beaumont and Nancy Newhall. We had a wonderful talk, and it was at that point that Beaumont asked if I might be interested in working with Nancy and him at the Eastman House during the summer. “But I don’t have any money,” he said. “You’ll have to find some way to deal with that.” And so I did it.

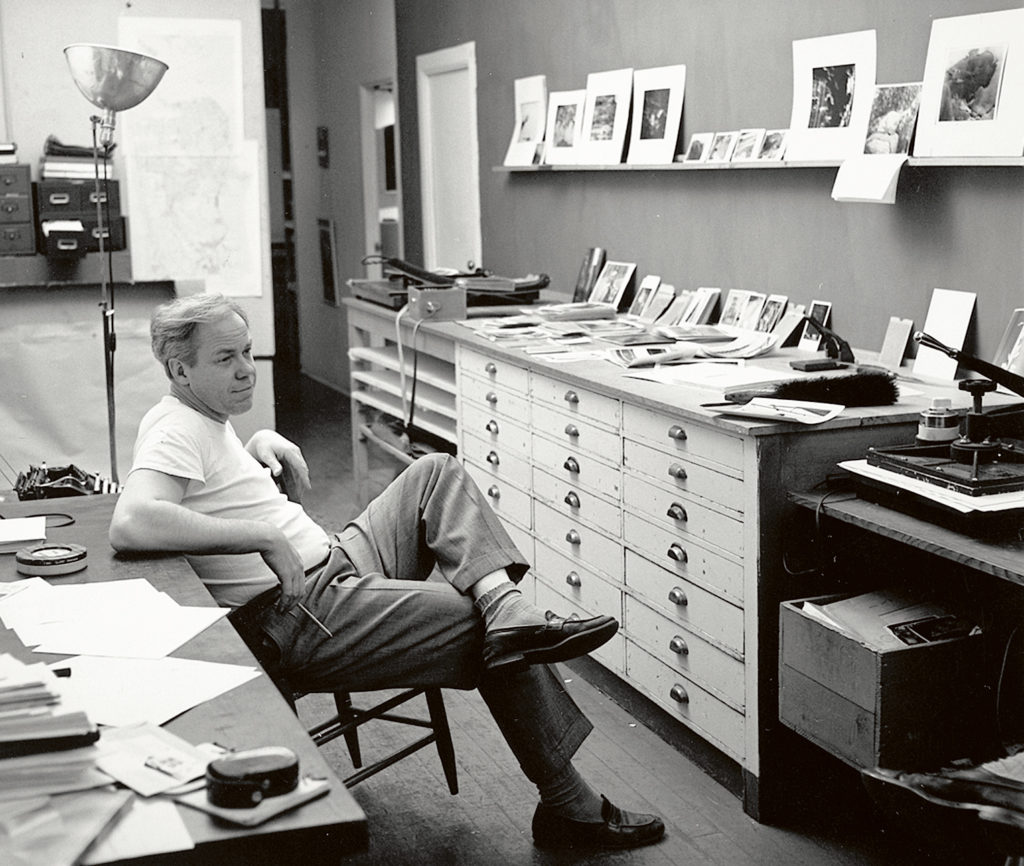

Image courtesy Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

Stoll: What did you do for them?

Bunnell: One summer I organized and cataloged the entire collection of Eadweard Muybridge’s motion studies and another I assisted Nancy Newhall with the research and editing of Edward Weston’s Daybooks. One year the Newhalls were putting together the Masters of Photography book for the publisher George Braziller. They would write an essay on a photographer, and then they would hand it to me and say: “Go pick out some prints to illustrate this.” So I would go and make some choices, and then they would look at them. “Why did you choose that one? That doesn’t have anything to do with the essay.” Then they’d say: “Get out such-and-such a portrait of Sir John Herschel.” So I would, and of course it was then obvious that that was the one that should be used.

Stoll: Were they always in accord with one another?

Bunnell: No. Nancy had a mind of her own. In fact, I’d say, if anything, Beaumont deferred to her. But Beaumont then ran the show at the Eastman House. They were building the collection. He had been the curator of the museum since 1948, and became the director in 1958.

Stoll: You mentioned that R.I.T. was one of the only places to study photography at the time. What other programs at universities existed in those years?

Bunnell: Well, things were just starting out. Among the first were programs at Ohio University, Indiana University, and the University of Minnesota. There was of course already the Institute of Design in Chicago, where you had Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind, and László Moholy-Nagy’s legacy, and the C.S.F.A., where Minor and Ansel founded the program. And there was the beginning of a coterie of students who were studying photography elsewhere as well, including on the graduate level.

Stoll: And, getting back to Aperture’s early audience, presumably that’s where some of the magazine’s subscribers came from, the students and faculty of those programs?

Bunell: Yes. The original subscription price was $4.50—today it sounds ridiculous! That was minimal, even for then. Still, I suspect that faculty would subscribe and then hand it around, and then, as the students began to make their own way, they subscribed.

Aperture matured slowly in terms of numbers of readers. In only a few years they were sending out notices crying: “Help! We’re running out of money—please come on board.” 1954 was a crisis year. Certain people did step in to help, and in 1953 the Polaroid corporation began to run a discreet ad, which really saved the magazine from collapse. But clearly, it was not a financial success.

Stoll: How did the magazine function logistically—I know it was a very small team of people that ran it.

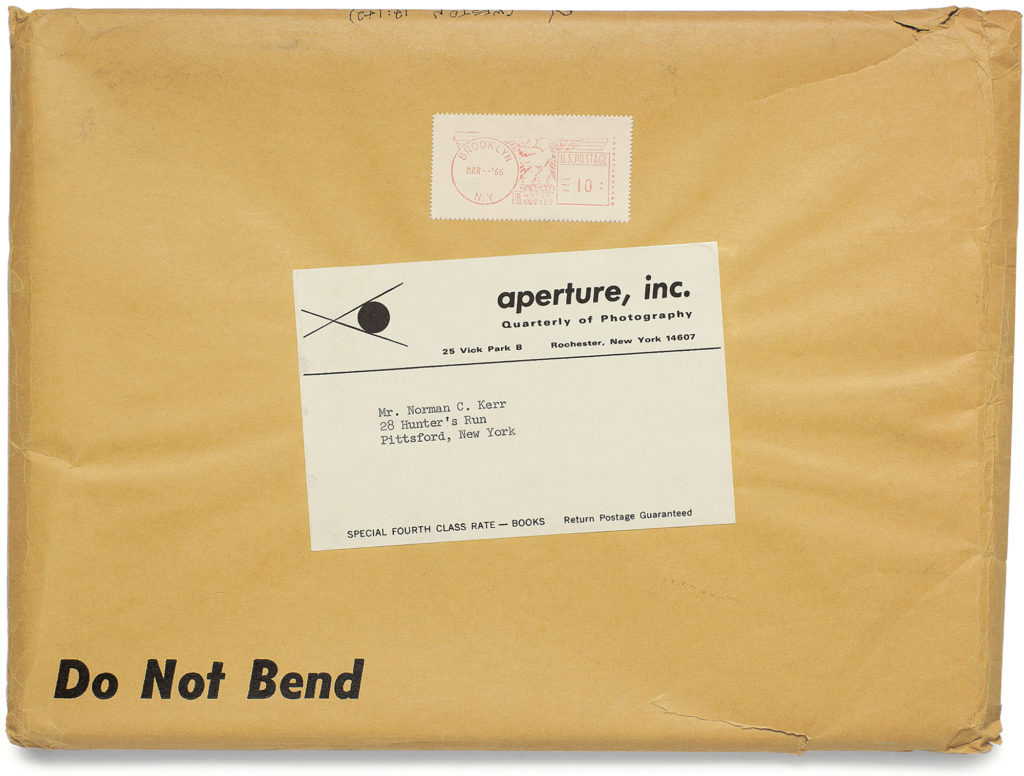

Bunnell: The magazine’s staff was minimal, to say the least. At that point it was edited by Minor in Rochester and printed by Lawton Kennedy in California, and the finished issues were then crated and shipped to Rochester. When I began working with Minor in 1955, I was the subscriptions secretary—I typed every mailing label (actually, I got pretty good at it). I did that for about three years. We had to put each issue in an envelope with postage stamps and these hand-typed labels. I would say that at the height of my years with Aperture it got up to maybe a thousand subscribers—but usually it ran more like five hundred people.

Stoll: There’s a sense that the circle of interest was so concise in those years that everyone reading the magazine must have known one another. There were also a few photography galleries in New York—Helen Gee’s Limelight in the 1950s and later on Light Gallery and Lee Witkin’s space—they must have played into the network of this community of readers, too. Anyone visiting them might also have had an interest in Aperture. What are your memories of those spaces?

Bunnell: I used to go to the Limelight with Minor. We would drive down from Rochester to the city and start at MoMA, then take the E train to Sheridan Square, where the Limelight was. The gallery opened in 1954 and closed seven years later, in 1961. It was a coffeehouse as well as an exhibition space, but it was the only gallery you went to for photography at the time.

In the ’60s a few other little spaces opened up. But really the key players—which had the idea that photographs were important (and for sale!)—were Lee Witkin starting out (his gallery opened in 1969), and Light Gallery (which was founded in 1971). Earlier on, Julien Levy (whose gallery opened in 1931 and ran through the 1940s) in the first few years showed almost exclusively photography. There was also a place called the Downtown Gallery, which as I recall was located in someone’s apartment.

Stoll: But the real, explosive success of photography would come a few years later.

Bunnell: Yes. And it was encouraged by Aperture in the sense that the magazine was where the list of many of the major photographers came from, more or less. Also, the great masters, notably Edward and Brett Weston and Ansel, were selling their photographs in portfolio form through the pages of Aperture. It was not a blockbuster situation—the Weston fiftieth-anniversary portfolio was advertised in Aperture for sale, and I think they sold only six.

But before its success in the market, this type of photography was really a kind of mission, a calling. It was almost a messianic thing. We believed in it, although it was not taken seriously by others, and it was economically overwhelmed by other kinds of photography. The idea that you would have a forum to show serious photographic work was almost unimaginable. I mean, it was Eastman House or the Museum of Modern Art, and that was it. (And at MoMA—until the 1960s, when they built an addition—the photo galleries were in the basement, outside the lavatories and the entrance to the museum’s cinema.)

So by necessity every avenue that Aperture could pursue, it did—they believed in photography. There is no doubt in my mind that the founders saw this as the new Camera Work.

Stoll: Obviously there were economic differences, and the era was not the same, but what were the philosophical similarities and differences between Camera Work and Aperture?

Bunnell: In some respects, there were very few differences. At the beginning of Camera Work, Alfred Stieglitz was propounding a new view of photography, which we now put under the heading “Pictorialism” (which of course had its variations). Over the life of the magazine his concept of contemporary photography, as with art in general, changed and the content of the publication was altered accordingly until, by the 49/50th issue of Camera Work, devoted to Paul Strand, one was very far from the Gertrude Käsebier featured in the first issue.

Similarly, Aperture was propounding a new kind of photography—a new vision of photography. It wasn’t Pictorialism, of course, but it was a new art for a different time; interestingly, however, it was based in part on that of Paul Strand.

Courtesy 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Stoll: And what about the writing?

Bunnell: I’d say there might have been even more writing in Camera Work than in Aperture. Stieglitz had a wide circle of literary acquaintances, who all wrote for the journal—from people like Sadakichi Hartmann to Joseph T. Keiley, John Kerfoot, Charles H. Caffin, and Dallett Fuguet. And because Pictorialism had a connection to the Salon movement, which was very active in those days, Camera Work had a lot of reviews. The publication also chronicled the Photo-Secession gallery exhibitions, and those elsewhere; this continued right to the end, in 1917.

Things were quite different in Aperture’s early years. Really, the opportunities for reviewing were fewer from the 1950s and ’60s until the beginning of the galleries era.

Stoll: I know that photographers generally weren’t paid for their contributions to Aperture. Were commissioned writers paid?

Bunnell: I don’t think anyone was paid. (Well, I was paid, but minimally.) Actually, if I remember right, there was one announcement that went out with the magazine and said straight out—I’m paraphrasing: “This is a work of love, and no one gets paid for content.” By emphasizing production costs, Minor was trying to justify the subscription expense, explaining to subscribers where their money was going.

Stoll: The subscription money went straight to production?

Bunnell: Yes: there was no other money available. I can remember even rationing long-distance calls. I mean, Minor didn’t get on a phone and call somebody and say: “Where’s your goddamn manuscript?” He wrote a letter and used a three-cent stamp, because he didn’t have the money to make a phone call!

Minor always lived very modestly himself. In Rochester he had an apartment above a hardware store at 72 North Union Street. One bedroom was made into the Aperture office, and the magazine was assembled in the large center living area. His darkroom was in the basement. Later on, when he left R.I.T. and went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he received a significant salary, so much that he literally didn’t know what to do with it. And on top of that, he had to perform socially. I remember going with him to Brooks Brothers to buy him a blue suit, so that he could go to events that he had to attend at M.I.T. I think the second time he wore it he spilled a martini all down the front, which stained it of course. (If you look carefully at photographs of him at the time, you can see this funny little stain.)

So Aperture operated on practically nothing in its early days—about five thousand dollars a year. At one point Minor wrote an editorial note saying: “We have simply run out of money for half-tones, for engravings, and so therefore this issue is all text.” Despite the simplicity of the first issues, very progressively, the magazine was seen as a quality-reproduction publication. And that is an aspect of Aperture that has been retained to today.

This interview is excerpted from Aperture Magazine Anthology: The Minor White Years, 1952–1976 (Aperture, 2012).

Diana C. Stoll is a writer and editor based in Asheville, North Carolina. She was senior editor of Aperture magazine from 2006 to 2013.