How to Be a Photographer Right Now

One morning at the end of February, I was sitting in Eisenberg’s Sandwich Shop, a grease-stained diner directly across from the Flatiron Building in New York. (Monas Eisenberg opened the shop in 1929, in hopes that it might get him and his family through the Great Depression.) I’d just arrived in New York for a flying visit, and I was feeling hazy and jet-lagged. Knowing that I’d be up early, I’d arranged to have breakfast with the photographer Gus Powell.

When Powell arrived, he wrapped his bag and bright red coat around the back of his chair and apologized for being a few minutes late. He’d just dropped off “the VIPs”—his children—at school in Brooklyn. Over our pastrami and eggs, we talked shop—mostly photobooks, new projects, his commercial portfolio, and parenting. We were both scheduled to have exhibitions and workshops at Micamera in Milan in the coming months, but because there were four hundred reported cases of coronavirus in Italy, it looked likely that our shows might get postponed for a few weeks. Powell was on his way downtown for a meeting with an advertising agency, and I was headed uptown to the Met, so as we hurried out into midmorning rush hour, we shook hands, hugged, and went opposite ways on a frenetic Fifth Avenue.

That was then.

Courtesy the artist and Lee Marks Fine Art

I often have anxiety-driven dreams, in which I’m endlessly racing through a crowded, anonymous, Gotham-like metropolis, trying in vain to catch a subway, train, or plane that I’m desperately late for. I’ve been having a lot of those dreams lately. Now, in self-isolation in my attic-cum-home-office in the southwest of England for the past nineteen days, I’ve started to wonder if I’ve gone stir-crazy. Had my breakfast with Gus, in fact, just been the opening scene to another one of these strangely pedestrian nightmares?

Courtesy the artist and Lee Marks Fine Art

On March 13, Bloomberg published a series of photographs by Powell titled What Social Distancing Looks Like in Public Spaces. “The editors of Bloomberg Businessweek reached out to me on March 4 and asked if I’d make a portfolio of images that showed signs of current ‘social distancing’ in New York,” Powell wrote to me recently in an email. “I’d already made a few images on the subway of hands avoiding poles, and had been thinking a lot about how to photograph public space in the city at this specific moment in time.” Powell shot the assignment throughout the following week. “I went to the busy places that I always frequent when I’m making my own work—the Financial District, Herald Square, Fifth Avenue—as well as areas that I knew would be farther along in terms of practicing social distancing, like Main Street in Flushing, Queens.”

Courtesy the artist and Lee Marks Fine Art

As Powell sees it, the pictures published by Bloomberg were those that represented the clearest manifestations of change, specifically hand etiquette on the subway. “But the ones that I’m most interested in,” he added, “are those where there is still little sign of change at all—pictures that may be a last look at public life in New York before COVID-19.” When I first saw his Bloomberg story, I was slightly worried about Powell’s safety, but he told me he hadn’t left Brooklyn since Friday, March 13. “I walked two-thirds of the way across the Brooklyn Bridge, and then turned back.”

Courtesy the artist/Magnum for National Geographic

Since the onset of the pandemic, many photographers have been seeking ways to capture this moment in time in a safe yet productive way. On March 20, National Geographic published a story online by the Tehran-based photographer Newsha Tavakolian about the “hard pause” the coronavirus has caused in Iran. (Its subtitle referred to the “suspended state of life in the country.”) “I was already two weeks into self-isolation when Nat Geo’s editors contacted me,” Tavakolian, who has covered social issues in Iran, Syria, and Russia, said by email. “I had to think about it carefully. Naturally, I was worried about the virus and about potentially infecting others, so I decided to try to make an intimate report. For the most part I stayed close to my own surroundings—although I did also go along on several disinfection patrols.”

Courtesy the artist/Magnum for National Geographic

Iran was among the first countries outside of China to be hit by the epidemic. By accepting the National Geographic assignment, Tavakolian explained that she “was trying to show the readers what sort of life was coming for them. Of course, citizen-journalists are capturing many things on social media, but I think that there will be a need for professional reporting now more than ever, as in the aftermath of all of this there will be plenty of debates about truths and facts. I hope that this massive crisis will lead to a renewed appreciation of our profession,” she added, “and a realization that independent reporting is key, especially in difficult times.”

Courtesy the artist/Magnum for National Geographic

The crisis is not only affecting photographers engaged in documentary and reportage, but also practitioners who work in a wide array of genres. “Art always feels somewhat inconsequential in times of real crisis,” lens-based artist Hannah Whitaker, who lives in New York and is well known for her experimental, multilayered and semiabstracted studio-based photographic approach, noted in an email. “But I know it’s important. It might not be able to get us out of this crisis, but it can help us out of our holes—like Ariana Reines’ recent new moon report, ‘Our Crown,’ in Artforum, which gave words to that strange combination of death and mundanity that characterizes this moment.”

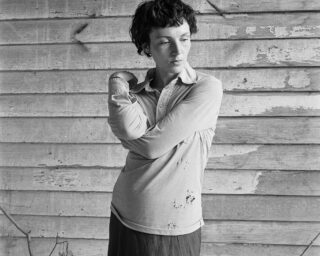

Courtesy the artist

For many studio-based artists and photographers, like Whitaker, social distancing and self-isolation are not entirely unfamiliar territory when it comes to being both productive and creative. “In some ways, my life is ideally suited for this crisis,” Whitaker explained. “Solitude and volatility are baked into being an artist, and usually I thrive in those conditions. I like being alone and normally embrace these kinds of structural limitations: What can I do with one sheet of 4×5 film? What photograph can I make with just the lighting and props I have on hand?” Whitaker acknowledges that she can walk to her studio, where she has all the equipment she needs, and can work alone—that is, when she isn’t looking after her three-year-old son. “But today is my day to stay at home with my son, who hasn’t played with another child in over three weeks,” she said, “so to be honest, I’m having a hard time.”

Courtesy the artist

The potential long-term effects of all of this are also starting to weigh on the minds of many photographers and artists. “I can deal with the normal ups and downs of my income and so on,” Whitaker noted, “but what’s new now is that I’m aware of the fact that this down may not be followed by an up for a long time, and may go deeper than any I’ve known. I know how lucky I am to be an artist, but I’ve worked my whole life to build this life as an artist—a life that is central to my selfhood—and that’s what I worry could be lost.”

From studio practice to commercial and editorial work, all photographers are aware that we are entering a new landscape. “Everything feels different now,” Powell told me, “and I’m uncertain about how to push my practice forward right now. There’s a different sense of time, which is simultaneously both intimate and global; sometimes the clock seems to be ticking very loudly, and other times not at all.” To keep himself busy and inspired, Powell explained that he’s reading a lot, looking at photobooks—“They still work, and will keep on working,” he stressed—and trying to make pictures of his life: his home, his children climbing trees, or the streets of Brooklyn from the driver’s seat of his car on a run for groceries.

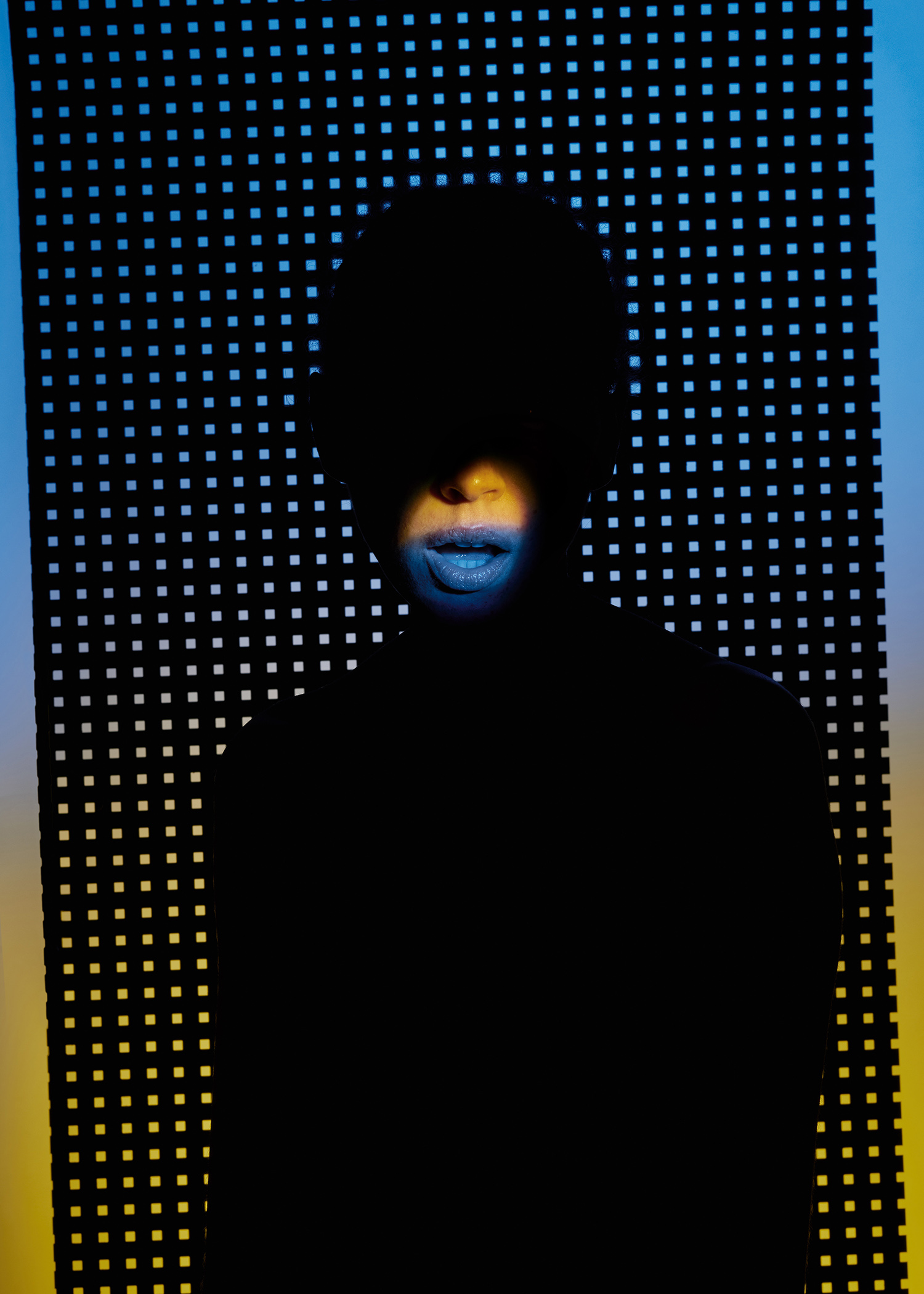

Courtesy the artist

“I’m not thinking about maintaining what I’ve already done,” Powell said, “but instead about how something new can be made, and about the kind of artist I want to be. I’m asking myself, How I can contribute to humanity with creativity and honesty?”

For Tavakolian, who has had her press credentials revoked several times in Iran, including just this past year, periods of being unable to work freely are nothing new. Like Powell, she sees the “pause” as an opportunity to broaden her vision. She suggests reading, slowing down, and revisiting unfinished projects. “I believe that this is a time to take in what is happening, and let everything sink in,” she said. “There will be a life after coronavirus, and we will be able to work and be creative. If there is any silver lining to this hard pause that we all face now as photographers—and as humans—it’s that disruption can lead to creativity. You can end up doing things that you never dreamed you’d do.”