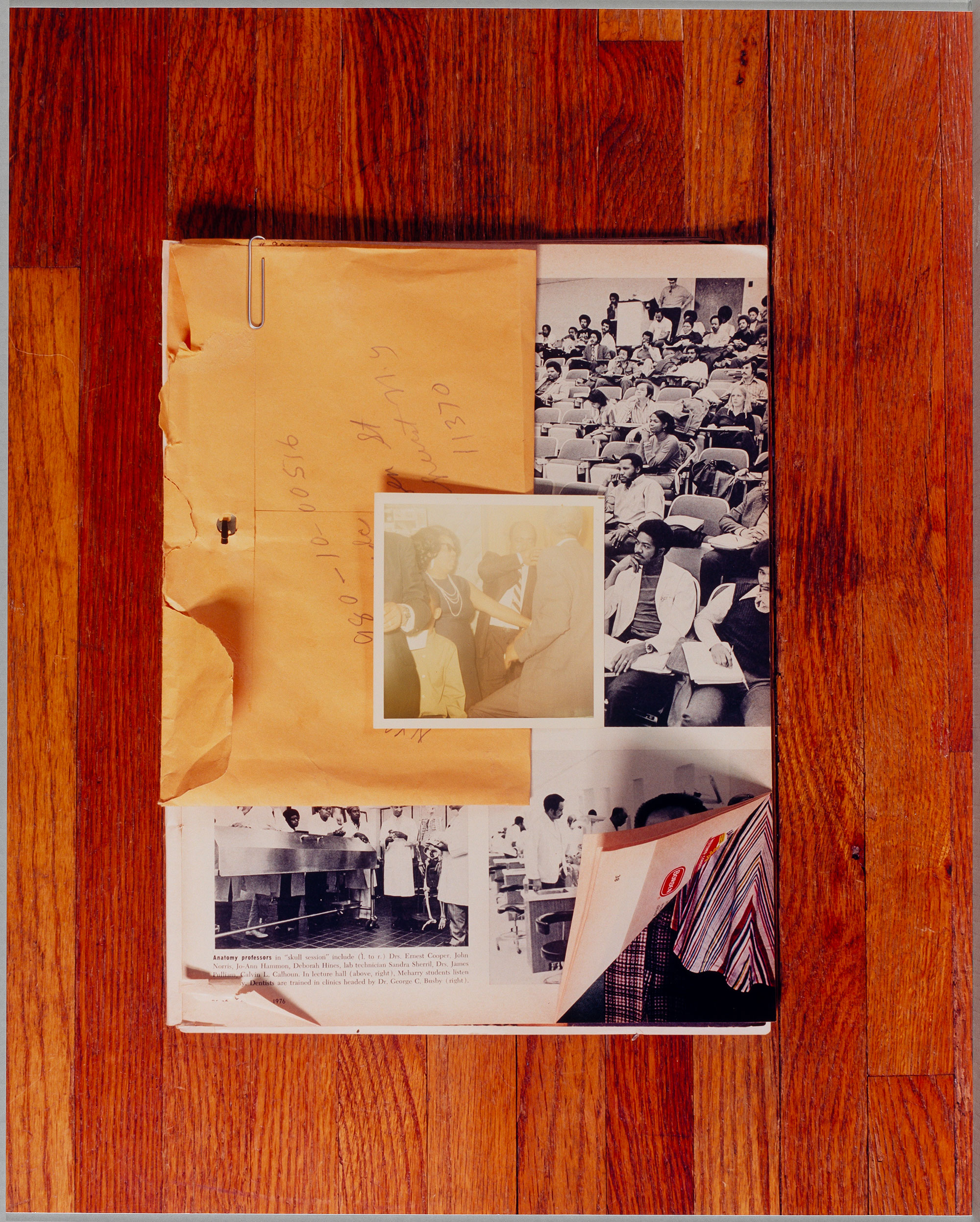

Leslie Hewitt, Riffs on Real Time (3 of 10), 2006–9

When Sadie Barnette was a kid growing up in Oakland, California, her father didn’t talk much about his time in the Black Panther Party. It’s possible he simply had other things to say. Rodney Barnette, who is now in his late seventies, has lived an uncommonly fascinating life. Born and raised in one of the oldest Black communities in the Boston area, he got involved in community organizing early on, followed the teachings of Malcolm X, was drafted into the army, earned a Purple Heart in Vietnam, took a job with the US Postal Service, joined the anti-war movement, took some time off to read W. E. B. DuBois and Karl Marx, helped the national campaign to free Angela Davis, and opened the first Black-owned gay bar in San Francisco, which for three crucial years in the 1990s offered a sanctuary and a site of resistance for the city’s queer communities of color. In the late 1960s, he also cofounded the ninth chapter of the Black Panthers, in downtown Compton.

Rodney may have been reluctant to discuss the experience with his daughter when she was little because of his lingering uneasiness about how the party had broken up and drifted away from popular community service initiatives like a free breakfast program for schoolchildren. He felt paranoid at times, but he was sure the movement had been infiltrated by informers who, through various disciplinary stratagems, damaged the party’s work from within. In 2011, Barnette sat down with his daughter and her mother to fill out a request for his FBI file through the Freedom of Information Act. It took more than four years for the file to arrive, not in the form of a dusty old box of papers but as redacted scans on CD-ROMS. Still, filled as it was with the blacked-out names of agents who were omnipresent and lied through their teeth, the file confirmed his suspicions, and so much more.

For several years now, Sadie Barnette has been transforming pages from her father’s 500-plus page FBI file into a series of ruminative artworks, embellished with surprising irruptions of pink spray paint, sparkly stickers, and glitter. On documents revealing patterns of harassment and intimidation that cost Rodney Barnette his job, among other things, the explosions of color read like expressions of love from a little girl to a daddy she adores. Three years ago, five prints from My Father’s FBI File; Government Employees Installation (2017) entered the permanent collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

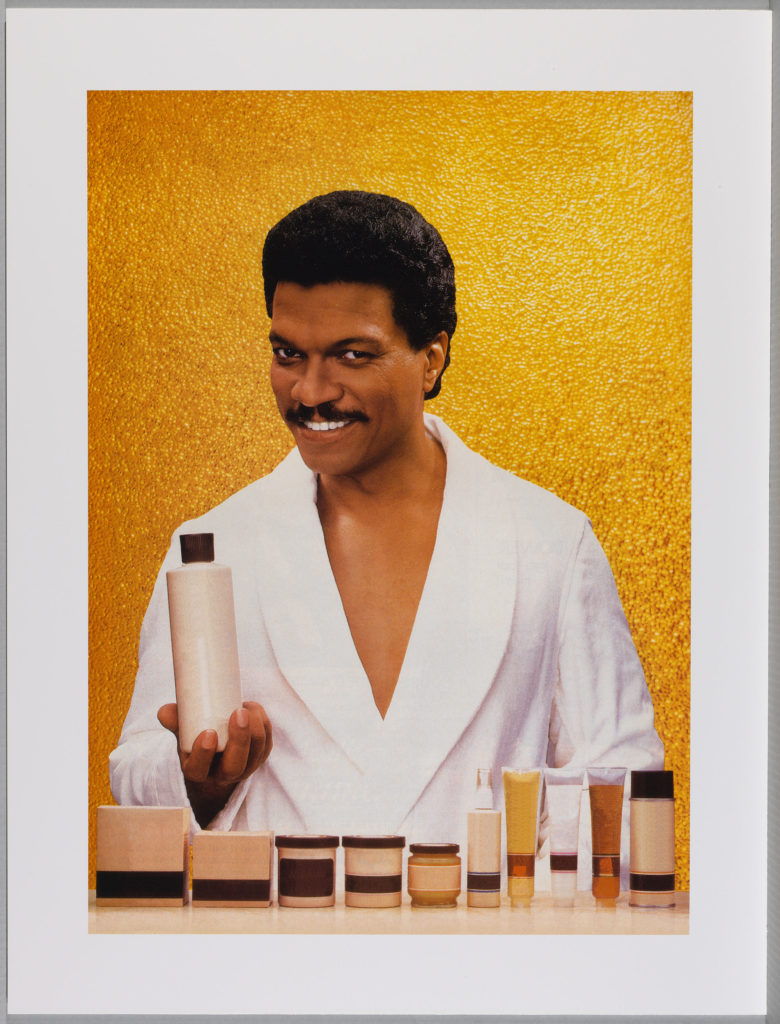

Thanks to the curator Ashley James’s ambitious, far-reaching, and decidedly self-critical approach to a collection survey highlighting recent acquisitions, an otherwise often dutiful form of exhibition-making, Barnette’s series is now on view throughout the summer. It holds its own hanging adjacent to a searing and powerful suite of prints by Adrian Piper as part of Off the Record, a bracing show of thirteen bodies of work, each of them challenging the role of documents (including official government records, newspaper pages, images from mainstream magazines, pedagogical tools, and scholarly photographic archives) in shaping, obscuring, or suppressing the histories they purport to tell. The exhibition fills a handful of side galleries with predominantly photo-based images that all but one of the artists (Lorna Simpson) used but did not themselves produce. The burst of pink on Barnette’s black-and-white pages signal the exhibition’s interest in interruptions and interventions, in the ways in which the featured artists have not only located and appropriated these records but more importantly acted upon them.

The archival impulse runs deep in contemporary art. Generations of artists have developed a veritable subgenre of documentary projects turning historical records into an artistic medium, from Hans Haacke, Martha Rosler, and Alfredo Jaar to Walid Raad, the Otolith Group, Mariam Ghani, Eric Baudelaire, Julia Meltzer and David Thorne’s Speculative Archive, Yto Barrada, and the Pad.ma project initiated in 2007 by three collectives from Mumbai, Berlin, and Bangalore. Obsessions with archival material tend to trace out some of the most intractable political conflicts on Earth, cohering them into a map of colonial and neocolonial cruelties. Off the Record moves in a similar way, cleaving to the core horrors of racism and power in America. But it also does something different.

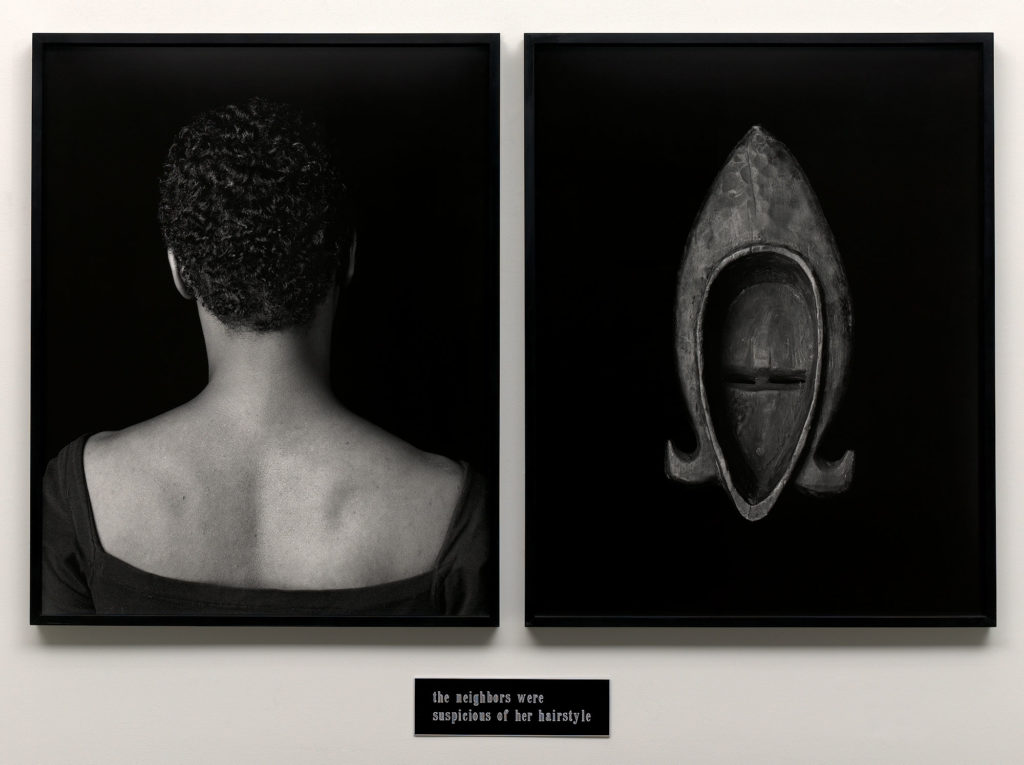

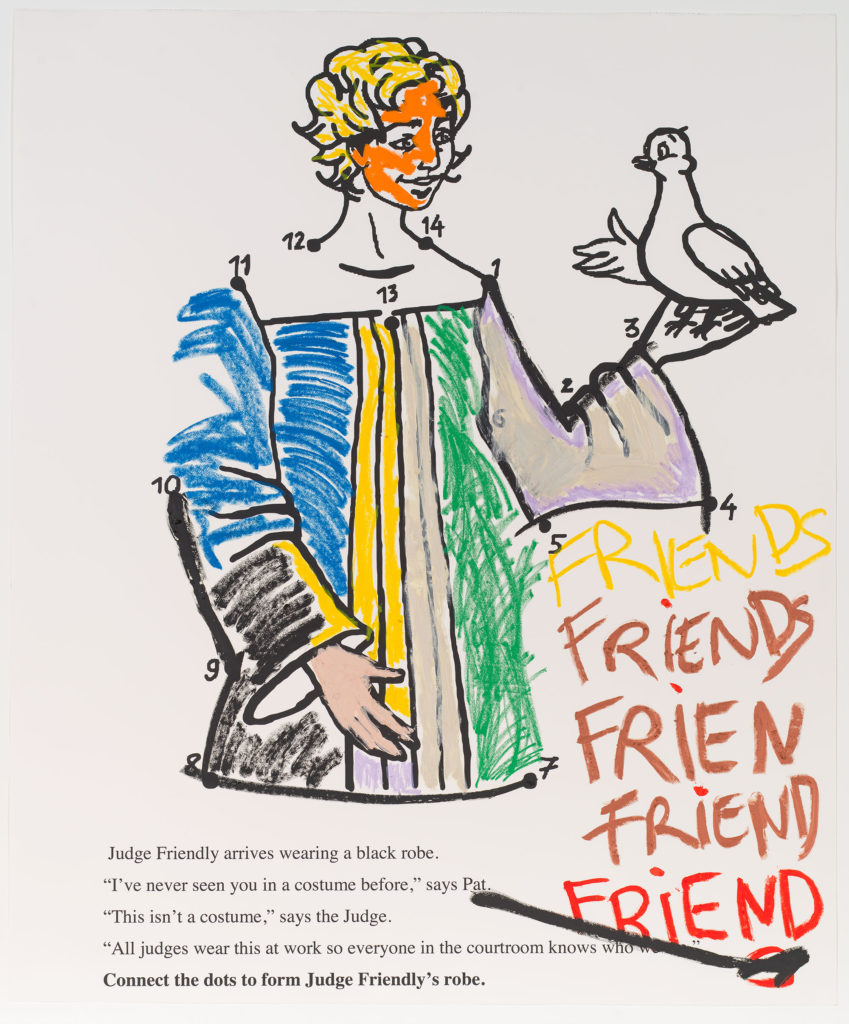

The title plays on the notion of going “off the record” in interactions with the media, when a source says something to a journalist that must, by convention, remain unprinted. According to James, the title here can also be understood as a verb, “killing” the record as a means of redress. All of this suggests not so much the melancholy engagements of a scholarly artist as archivist, working through old dusty photographs as forms of evidence, storytelling prompts, or mnemonic devices. The artists in Off the Record are more actively engaged, more playful and pugilistic. Through acts of repetition (Glenn Ligon), deletion (Hank Willis Thomas), subtraction (Sarah Charlesworth), juxtaposition (Lorna Simpson), collage (Leslie Hewitt), brutal captioning (Carrie Mae Weems), they actually seem to tussle with their materials and win. In Coloring Book 9 and Coloring Book 18 (both from 2018), Sable Elyse Smith willfully colors outside the lines on the enlarged pages of children’s activity books introducing the justice system and the carceral state; in Ecology of Fear (Gillum for Governor)(Freedom Riders Bus Bombed by KKK), from 2020—and the only work on loan in the show—Tomashi Jackson creates wells of tension and emotion by layering lines and colors into an accumulation of found images printed on clear vinyl, including an enlarged photograph of Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act into law, the face of Martin Luther King Jr. just visible in the background.

Like many museums in New York and around the world, the Guggenheim has struggled—and sometimes stumbled—in its efforts to address the wider systemic racism of the art world and the urgent need to diversify its exhibitions, collections, leadership, and staffing decisions. Off the Record presents a strong example of how curators with fresh eyes, real vision, and deep art historical knowledge might begin to reform institutions from within, rifling through their own collections, materials, and records to find the pieces of vital new arguments to be made. (James, who previously worked on blockbuster exhibitions such as Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, as well as solo shows devoted to Adrian Piper, Charles White, Eric N. Mack, and John Edmonds, joined the Guggenheim in 2019.)

All works courtesy the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

In an interview with her father that Sadie Barnette recorded a few years ago for the Studio Museum in Harlem, where she was once an artist-in-residence, she asked him where his political convictions began. He told her the story of finding a photograph of a lynching in The Pittsburgh Courier, a leading Black newspaper in the first half of the twentieth century. He was horrified by the cheering crowd in the picture. In another interview made for the current show, Barnette reflected on how their father-daughter story is bigger than them; it is a family story that speaks to universal experience. But she also admitted, about her pink adornments on her father’s FBI file: “How powerful it does feel to know that just me and my small self with my spray paint in my studio can interject.”

Off the Record is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, through September 27, 2021.