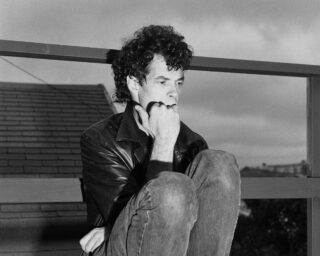

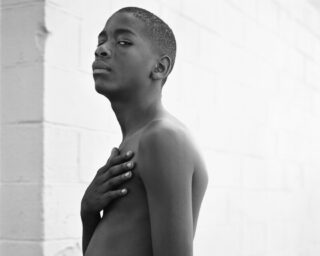

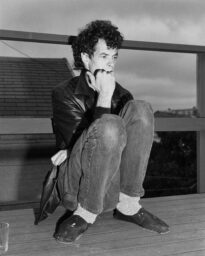

Inuuteq Storch, from the series Soon Will Summer Be Over, 2023

For Inuuteq Storch, photography is a way to recast history. Growing up in Sisimiut, a town of around five thousand people just north of the Arctic Circle, the thirty-six-year-old Kalaaleq artist found that much of the visual culture depicting Greenland had been produced by foreigners or colonial historians and adventurers. Greenland, which was colonized by Denmark more than three hundred years ago, became an autonomous territory in 1979. Yet today, the territory continues to face external threats, most recently in the form of escalating warnings from President Trump of an American takeover of the region to safeguard “national security.”

Over the past ten years, Storch has documented fleeting moments of daily life and routine across Greenland, navigating the complexities of Inuit traditions, Danish colonial influences, and growing environmental crises. His photographs are raw and intimate, oscillating between granular detail—laundry hanging to dry, teenagers lounging outside, domestic interiors filled with family photos—and the almost boundless presence of the Arctic landscape, which he portrays in a manner that resists spectacle. His attention to bold colors often heightens the intensity of otherwise quotidian scenes and encounters.

In 2024, Storch became the first Greenlandic artist to represent Denmark at the Venice Biennale, mixing his own photographs with personal and historic archives. His current show at MoMA PS1, in New York, Soon Will Summer Be Over, organized by Jody Graf, marks his first solo exhibition in the United States. It highlights three bodies of work from the past decade alongside a two-screen video installation comprised of rare mid-twentieth-century footage filmed by Greenlanders. The gallery walls are painted in shades of navy and olive green, creating a range of moods. In December, I spoke with Storch about returning to Greenland after studying photography in New York, working with historical archives, and why he finds time to be “a beautiful, complicated thing.”

Cassidy Paul: How did you first get started with photography?

Inuuteq Storch: My mom took a lot of photographs when I was a kid. From time to time, I would find my father’s old cameras. When we found them, my parents didn’t let us play with them. I used to skateboard, but I was not one of the good ones, so many times I was the cameraman. At some point, a friend of mine convinced me to buy his camera, and I had to convince my father to buy it. That’s actually where it really started.

Paul: You went on to study photography, both at Fatamorgana School of Photography in Copenhagen and the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York. At that time, how long were you away from Greenland, and what spurred you to return and begin photographing there?

Storch: It was the second time in my life that I moved away from Greenland when I studied photography in Copenhagen. I didn’t have any photography friends, and I didn’t know people made photobooks, or that a lot of exhibitions are photo-based. I’m so far away from that. Then I figured that photography has a big role in society and we don’t have a main photo culture here in Greenland. I wanted to be an engineer, but I was like, Nah, not anymore. I want to be a photographer now.

Paul: Really? When did you make that pivot from engineering to photography?

Storch: I was still going to become an engineer, but right after I finished school in Copenhagen—I did that from a sabbatical year before I started the education—my teacher was like, Maybe you should go and try to apply to ICP in New York. I was like, Oh my goodness, New York. I thought that was cool. Then I started trying to go there afterward. When I moved to New York, I was like, Nice. I might live there forever.

Paul: But you didn’t?

Storch: No. At the end of the year, I was like, Okay, cool. I can be here. But if I moved back [to Greenland], I will make more important work than if I kept staying in New York. In New York, I will still make good photography, but it will be less meaningful.

Paul: What did that feel like to come back and to put this together at MoMA PS1?

Storch: It was very good to see. I was very nervous. I was more nervous than at the Venice Biennale.

Paul: What was that distinction?

Storch: For MoMA PS1, you cannot dream about that. It was the same with Venice. You cannot dream about it. It’s too big—and then it happens. Then you are like, What? What do I do now? Also, this time my exhibition is a lot more formal. The way it’s hanged, it’s a very calm exhibition compared to the exhibitions I usually do.

Paul: Your installation at the 60th Venice Biennale had a beautiful, constellation-like installation. What was the process of putting together this show at MoMA PS1?

Storch: Luckily, the team from MoMA PS1 are very good and always showed me what the plan was. I let them decide everything.

I also got good inspiration from that—frames, passepartout, different kinds of sizing—for showing my work. This is not the first time I let the curators decide how to exhibit. It’s either I decide everything, or curators decide a lot.

Courtesy MoMA PS1

Courtesy MoMA PS1

Paul: Do you like seeing that process of letting a curator or an editor come in and put something together with your work?

Storch: I like doing that so I get inspirations on how to do it differently. Also, other people see different pairings with photos. That usually is very inspirational for me.

Paul: Was there something outside of the framing in this show that the curator did that really inspired you or surprised you?

Storch: Yeah, the colors. I have already done colored walls before, but very based on Greenland—the older, elderly home with these specific colors. This was different. It was taken from one of the colors from the images. So that’s really cool.

Paul: One of the rooms features an ochre tone. That warmth, paired with the often cold, icy tones of your photographs, created a really interesting dynamic.

Storch: I really like the warmness of the whole place together. It’s very nice.

Paul: I’d love to hear a bit about your process. In the exhibition, the curator states that you work with a variety of cameras, some of them passed along from family or friends. What does your approach in making these images look like? Do you plan things in advance, or naturally come upon these scenes in your day-to-day?

Storch: It’s very natural and exactly as you say: walking around meeting people. I don’t know. I go by feelings when I decide which camera to use: 35mm is a lot faster. It’s better to be close with people and very moment-based. I don’t need to interact a lot with people when I use that, I just take a photo. Then 60mm, I need to talk to people and it’s a lot slower. Can I take a photo? I’m going to step back and make the correct settings and take the image.

Paul: Is there a sense of collaboration with anyone that you’re photographing? Or does everyone just know that you’re here with your camera and you’re going to be shooting [laughs]?

Storch: Definitely the latter, yeah [laughs].

Paul: One of the series in the exhibition, What If You Were My Sabine? (2019–25), reminded me of a well-known body of work by Jacob Aue Sobol, Sabine: A Love Story. I’m curious who or what are your sources of inspiration.

Storch: I’m a fan and he’s a friend of mine as well. Sabine is my favorite foreigner’s work in Greenland. It’s the most authentic. It’s not about us, it’s about his love—that’s the difference. A lot of people are like, Look at these exciting people. Jacob was actually a hunter at the time when he photographed Sabine, who is from East Greenland.

I’m inspired by a lot of Greenlandic music, but also Greenlandic history. I grew up not knowing a lot about our culture. Nowadays I have tattoos based on Greenlandic culture, a lot of things and people that I never knew. I used to be scared of shamans, but they are the reason that we survived, helping spirits. I listen to all kinds of music—I love Danish music, Greenlandic music. I love international music. Around this time, I’m listening to a lot of tango. It’s very emotional music.

Paul: Do you listen to music when you’re photographing?

Storch: Yeah, I listen a lot of the time.

Paul: You’ve published a few photobooks and have had multiple exhibitions, and I’m curious, do you go back and share this work with anyone you’ve photographed?

Storch: Depends. Some I have never met again and had no conversation or connection again, but some are friends. I’m really bad at sending photos. Once in a while, they will ask and I will send them. But I’m not very good at it. With those friends I made, I stay in contact not because of the photos but out of friendship that we have.

Paul: There’s a unique aspect to your photographs where the landscape holds an extremely significant presence while also, at least visually, is downplayed. What is your relationship to this landscape, and what role does it play in your work?

Storch: Nature is a very big part of our lives here in Greenland. It’s the deciding factor many times a year. I spend a lot of time in the nature. Greenland’s nature is very beautiful and very dominating. I think it’s very difficult to make it not a main element in photography.

Paul: I feel like it’s really not the most prominent thing that I see when I look at your photos.

Storch: Yeah, it’s because I try hard. It’s very, very easy for the nature to be the main element in photography, especially here in Greenland. That’s one of the hardest challenges that I think about.

Paul: What really sticks out throughout your work is just the everydayness of these images. As soon as I walked into the exhibition, I noticed the first photo on the wall with the yellow car, and it felt like a photo that I could see taken anywhere. It seems like that’s something that you are striving for. Do you think that that’s true?

Storch: Yeah, that’s very true. One of the best compliments I’ve ever gotten is someone, after looking at a book, he told me that he was homesick.

Paul: I think that that’s very much a feeling that comes out of viewing this work. There are some scenes that I felt like even from my own childhood, I could see it in these moments.

You talk about how the landscape is one of the challenges that you’re working through. What are some of the other challenges that you feel like you’re contending with when making this work?

Storch: From time to time, I think differently. Today, I think it’s not so difficult. Usually I feel pressured to take photos—that I need to take more photos—but that’s not actually a real challenge, so it’s not really true. But probably time. I will say time. Time is the most challenging when I take photos.

Paul: Time definitely feels like a narrative that’s woven throughout the exhibition. You have this play of archives—slide photographs from your family, a two-channel video with footage from the 1950s to 1970s—where you’re creating these conversations across time. On the other hand, there are these extreme stretches of night and day in Greenland where time seems to stand still. What does the concept of time mean to you?

Storch: Such a complicated topic. Sometimes when an older man or woman dies, and someone else is born, they’re named the same name and you will call them “my little mother”or “my little father.” Sometimes, I feel like time doesn’t exist; it’s just different timelines all living together. Sometimes I feel like we’re going backwards with time, sometimes we are running away from time. It’s a beautiful, complicated thing.

Paul: That’s lovely. I know at the Venice Biennale you pulled in the archives of John Møller. What has driven you to bring in these different archives, and where did your interests start with that?

Storch: When I was younger, I thought I really had to press the camera’s release to take a photo. If a friend of mine took a good photograph, I’m like, That’s not mine. But at some point, I was hanging out in a dumpster with a friend and found film and actually went and made a project out of it. I figure, I don’t need to take the photographs to tell my own story. I started digging into my parent’s photos, and thought, Oh, this is actually enough for a book. I can divide this project across many different situations. Then I went to a museum with a friend to see his great-grandfather’s musical instruments and ran into a diary with a lot of photographs. The workers showed me the whole collection of John Møller—the very first Greenlandic photographer. Greenland’s history is largely documented by foreigners. The Inuit way of telling stories is so different compared to European or Western ways. This is when I thought, We can actually use photography to retell our history.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Wilson Saplana Gallery, Copenhagen

Paul: Møller’s photographs create such a dynamic pairing with your own work because they are so formal. Of course, his work is of its time since the snapshot didn’t exist in the way it does now, but that contrast between his and your own images once again returns to that bending of time you thread throughout your work.

This transitions to something I’m curious about. What interested you to start documenting the people in your life and these small moments of the everyday? Because it seems like you started photographing at a young age, but I wonder if you had a moment where it shifted into becoming something more intentional.

Storch: It was actually around the time in New York that I decided how I was going to form my project. I figured in New York, when I speak English and when I speak Greenlandic, I’m a very different person. I went to Greenland for Easter break and realized, Oh, places also do the same thing. I’m a different person in New York, and a different person in Nuuk, or Sisimiut. Basically, I decided that I wanted to work and create place specific projects to map identities in those places.

Paul: Greenland obviously has a long colonial history with Denmark. How do politics fit into your work? Do you see that as a motivator when you’re photographing?

Storch: Not a lot. My parents are still very into politics. As a young man, I didn’t like politics a lot. I don’t think the way they work are as effective as it should be, but every person who is alive is involved in politics. My work automatically becomes political because I’m from Greenland, which has this historical relation to Denmark. Even though I don’t think about politics, my photographs become political at some point.

Inuuteq Storch: Soon Will Summer Be Over is on view at MoMA PS1, New York, through February 23, 2026.