Tokuko Ushioda, Untitled, 1978–83, from the series My Husband

In the late 1970s Tokuko Ushioda lived in a modest fifteen-tatami-mat apartment with her husband and their newborn daughter. They lived sparingly. A couch doubled as a guest bed; the kitchen consisted of a table in the corner; they shared a downstairs bathroom with the building’s other residents. One day, her husband arrived home with an old Swedish refrigerator that Ushioda described to be as large as a polar bear. The hulking appliance, much too big for their space, malfunctioned from the beginning. It froze vegetables solid and at night rattled like a poltergeist, stirring anxiety and fear about the future in Ushioda’s mind.

She found peace with the appliance by making it her subject. Using a six-by-six camera mounted on a tripod, she began a ritual of photographing her home invader straight on, with its door open and closed, and over time created a Becher-like typology. Closed, the appliance is an imposing, utilitarian tower, a sleek but vintage example of industrial design. With its heavy door agape, it is less imposing, even vulnerable. Anyone who has had a house guest rummage inside their fridge knows how this appliance is the kitchen’s underwear drawer, revealing a diary of culinary tastes, habits, and degrees of cleanliness. Intrigued by the process of studying her own fridge, Ushioda began to photograph those belonging to her landlord and family members, working according to the same set of formal rules.

Courtesy the artist

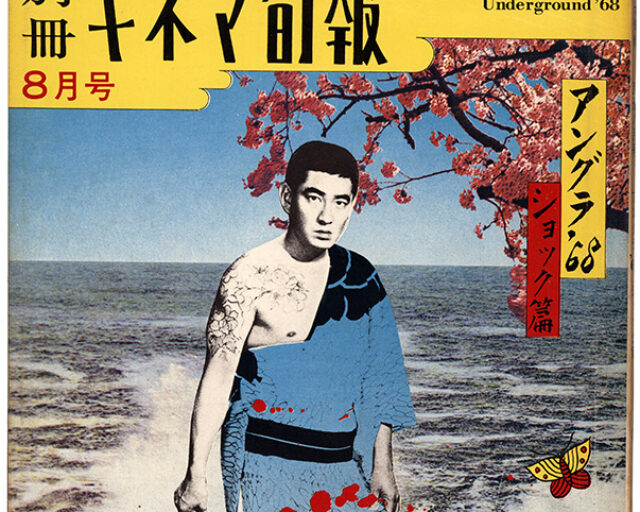

For Ushioda, a mother who was often at home, the domestic realm has functioned as a site of curiosity and creative possibility. She works in a tradition of photographers who candidly observed the details of their own existence, long before social media normalized, monetized—and exhausted—doing so. A related series, My Husband, portrays ordinary scenes at home with her spouse (also a photographer) and their then newborn daughter. This is a family album that is loving without being saccharine or sanitized; the messiness of life is left intact and on display.

Both projects were recently exhibited at the Kyocera Museum of Art, Kyoto, as part of Kyotographie, the annual international photography festival that presents exhibitions across the city, often in notable architectural venues. “There is a certain quietness to the space with the ordinary scenes of the mundane being framed and displayed,” Ushioda says of the exhibition. She is an astute observer of small, everyday moments, accumulating detail upon detail, which, assembled together, decades on, unsentimentally describe the passage of time.

Courtesy Takeshi Asano and Kyotographie

Courtesy Takeshi Asano and Kyotographie

Her desire to archive her own life extends beyond photography. The exhibition also included vitrines filled with personal belongings, toys, children’s shoes, mannequin hands, a film canister, jewelry, among other sundry items—relics of her past. “I have a habit of keeping ridiculous things, like the umbilical cord and fingernail clippings from when my child was born, or their baby teeth,” Ushioda says. “We cherish the things that we have, things including my husband,” she laughed—her response knowingly pointing to how photography is always partly an act of objectification and preservation.

Her work from this period, 1978 to 1985, was discovered by chance. Five years ago, while cleaning a room, she came across a box of prints in the back of a wardrobe that held a time capsule of her life. My Husband was collected in a celebrated volume published by Torch Press in 2022. For the exhibition in Kyoto, she was selected by Rinko Kawauchi, a photographer of a younger generation who is also renowned for her close studies of the almost invisible phenomena animating the everyday, picturing what might be deemed mundane with absorbing reverence and attention.

Courtesy the artist

In an adjacent gallery in the museum, Kawauchi presented a project titled Cui Cui (2005), after a French onomatopoeia describing a sparrow’s twitter: a metaphor, in Kawauchi’s mind, for how the accumulation of minutiae forms the fabric of family life. Through her gaze, the cycle of life unfolds, image by image, charting events both large and small. Details of hands reveal the softness of youth or the leathering of age. Her young daughter, arms outstretched, reaches forward to register the novelty of a breeze. Sunshine, air, texture—everything is available for the senses. Here, in contrast to Ushioda’s more documentary, black-and-white images, life manifests within a dreamy atmosphere awash in soft pastels and diffuse, angular light. The death of Kawauchi’s grandfather, the marriage of her brother, the birth of her own daughter; time passes, cycles of life carry on. “Looking through the camera’s viewfinder feels like peering into a window,” Kawauchi notes of the commonalities of her work and Ushioda’s. “We share the world we are peering into.”

Kyotographie 2024 was on view at multiple locations in Kyoto, Japan, from April 13 to May 12, 2024.