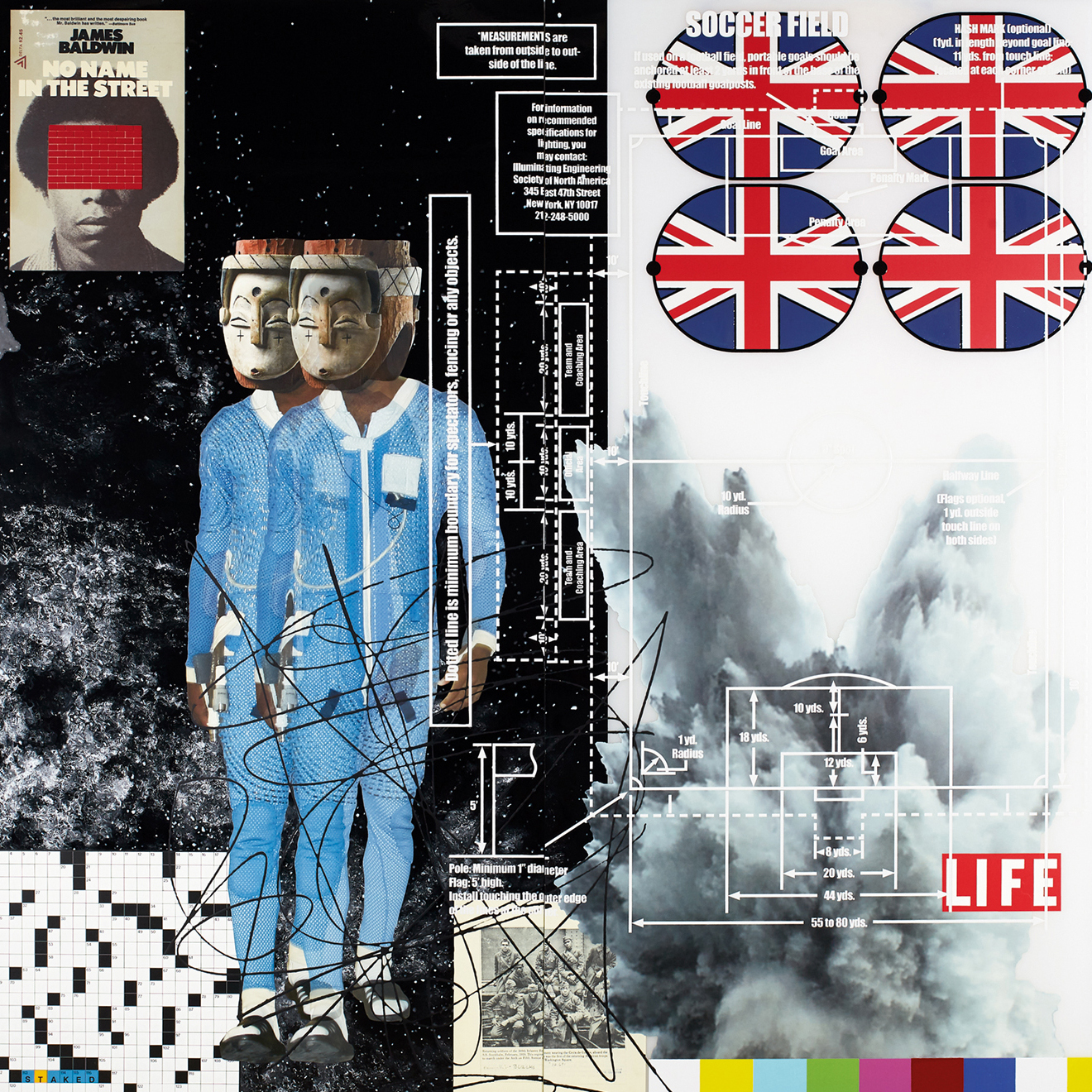

Tavares Strachan, Resinol Soap, 2018, from the series Notes on Exploration

The artist Tavares Strachan makes enormous neon sculptures, immersive installations, and accumulative two-dimensional series that layer historical photographs of monarchs, explorers, and musicians over and under drawings, advertising images, traditional geometric patterns, and technological glitches such as the smudges from a printing error or the wavy lines and test patterns of television broadcast interruptions. His best-known projects take performance to an outrageously global, even cosmic scale—moving a four-and-a-half-ton block of ice from the Alaskan Arctic to a freezer in the courtyard of his Bahamian elementary school, in 2006, or placing a 24-karat gold canopic jar bearing the bust of Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., the first African American astronaut chosen for a national space program, into a SpaceX rocket that has been orbiting Earth since 2018.

Strachan speaks of his work in terms of a West African street festival where dance, poetry, music, and the performing arts are jumbled together in an exuberant whole. It’s hard for him to separate out any one medium, to speak of photography, say, or sculpture, in isolation from his other modes of making. As he explained to me one day in early June, speaking from his studio in New York, so much of what he is trying to do, as someone who was raised in an Afro Caribbean home (he grew up in the Bahamian capital of Nassau) but graduated from high powered Western institutions (RISD, Yale), is about reconnecting the experiential elements of the former that were pulled apart by the organizational systems (and colonial undertones) of the latter.

Strachan compares the process of making the pieces in series such as Notes on Exploration and The Children’s History of Invisibility (both 2018) to the loose structures of 1960s jazz, “with a little bit of dub and a little bit of hip-hop,” he says, adding that “those genres speak to each other.” They respond to a rift or a clue. “I think, visually, I’m doing something similar with images, textures, the pieces of a story.” These works have the appearance of large-scale collage, but more often than not, they are made from images printed on layers of Mylar and vinyl mounted on acrylic or museum board. Strachan also calls them poems, assembled from a language that is never innocent or transparent but can be wrestled into a form that speaks to (and about) systems of power.

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

A work such as The Stranger (2018), for example, might begin with an image of Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia who galvanized public opinion, inspired the Rastafarian movement, and, incidentally but tellingly, kept massive pet cheetahs as his preferred symbols of power. From there, Strachan builds the surface sonically, adding a delicate line drawing of a maze; a Lion of Judah flag, which he used to see everywhere in his neighborhood as a kid growing up; a Life magazine cover featuring the astronaut John Glenn alongside a headline about women’s intimate apparel; and a photograph of himself in a cosmonaut suit, his head obscured by an oversized, performative mask. He’s particularly drawn to materials with double meanings, such as Native American textile patterns that not only are decorative but also serve as maps or other such communication channels.

“Duality allows for a certain level of elasticity in how we think about the world,” Strachan says. “Instead of spending all this time thinking about how we are different, it allows for thinking about sameness, about overlapping and intersecting, about all kinds of complexity. My own history, my erased history through colonialism, my new history as someone who’s been living in the United States for some time in a society that wants you to decide you are one thing or another—all of that goes into the work.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies.”