In the West, Carolyn Drake Seeks New Expressions of American Identity

Carolyn Drake, Wyko McKee working on his friend Johnny Pavkov’s ranch for the summer, Gooding, Idaho, 2016

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Sometimes you need the eyes of an outsider to see your world afresh. The sustained focus of the newcomer; the quizzical glances of the passerby; the curiosity-filled wanderings of the traveler—they refresh our ideas of ourselves and help us rediscover the familiar. Indeed, they even render the invisible visible. Seeing alongside outsiders expands our scope—and, at its best, deepens our understanding and appreciation—by returning us to a childlike inquisitiveness. As the Polish poet Wisława Szymborska wrote, “there are no questions more urgent / than the naïve ones.”

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Carolyn Drake, who has photographed across the world (notably in western China and the Ukraine), where she benefited from the outsider’s remove, returned in 2013, after seven years away, to her native United States and chose to pursue the naïve questions by adopting the stance of a stranger. In fact, she had become a stranger of sorts—much of her country felt foreign, as she had been “thinking about other places for a long time.” But she was also too close to her country, and it too much a part of her, for her to see people and their environments as clearly as she desired. She needed to revisit her homeland with a new way of looking.

She decided to counter her disadvantage by traveling westward, using the nineteenth-century diary of an ancestor who, during a time of national expansion, went from Iowa to California. The diary is both guide and point of departure; Drake wanted to undertake a journey with a personal connection, and connect with those she encountered, not, as she said recently, “re-enact the journey or reaffirm our national mythologies. Rather, I’m seeking out stories that subvert and confound the boilerplate Western narrative.” She not only traversed the landscape, but also circled it, paying patient attention to those who sprung up from the soil and those new to it.

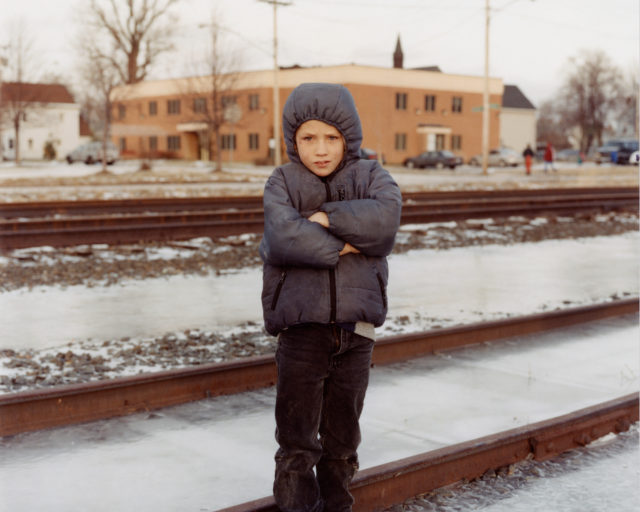

Abandoning the romantic myths of the frontier for the stories that animate those in pursuit of or left behind by—or even unconcerned with—the American Dream, Drake captures the worlds she encounters with warmth and lyricism. A family of African refugees traveling from Boise, Idaho, makes a pit stop at a gas station in Baker City, Oregon, to pray and refuel. We’ve seen this gas station before—a staple of American realist photography—but this scene feels fresh, different: friendly banter with a stranger illuminates the life often found in the societal interstices between those from here and those from elsewhere. The encounter resembles a delightful community gathering; perhaps we haven’t seen this gas station before, after all.

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Drake gives us people inscribing themselves on the landscape—which might mean inscribing the place on one’s very self (a tattoo of the state of Idaho adorns a man’s back, its vibrant colors at once badge and beauty), or asserting one’s agency in a place where daily life threatens to be a rote cycle of quiet desperation. Her interplay between the roles of insider and outsider suffuses her photographs, and we meet people who are as beguiling as they are mysterious: her subjects (students, refugees, workers, the unemployed, to name a few from a very broad range) draw you in with arresting gazes, but a moody atmosphere—those warm colors—holds you at bay, searching. It’s as if Drake invites us to see people’s agency, then insists it not be denied them—the African refugees’ smiles, expanding the photograph’s frame, intermingle with their veils. In their mystery is their magic.

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Drake is rediscovering—discovering, really—the United States as a native-made-newcomer, and as one tracing a path behind those whose footsteps reveal the wild, varying textures of a nation too often reduced to myths, stereotypes, and clichés. “What is America to me?” her work asks, pointing to the outsiders, the recent transplants, the strangers among us. Will they be strangers forever? Or will they eventually be welcomed as Americans, too? Carolyn Drake reminds us, to borrow Robert Frost’s words, that “America is hard to see.” We ought not to forget, then, that the meaning of America is bound up in the treatment and fate of those who see the way we don’t.

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 226, “American Destiny,” Spring 2017.