Inside the Spring Party with Penelope Umbrico

For this inaugural event, Aperture has teamed up with artist Penelope Umbrico to offer each party attendee a unique, signed photograph from Umbrico’s Moving Mountains series.

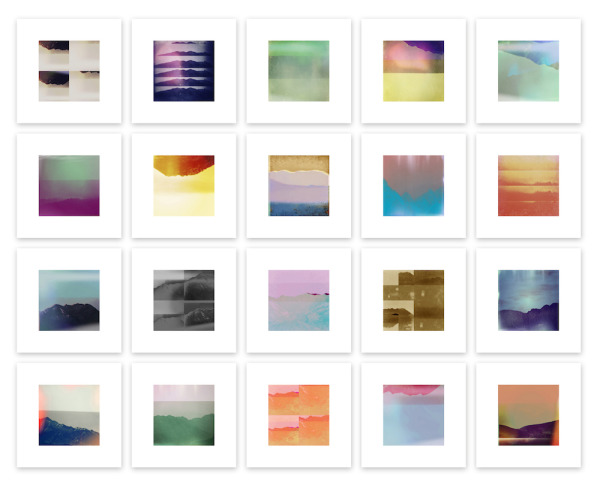

Detail of 350 Mountains (with Smartphone Camera App Filters) for Aperture Spring Party Edition, 2015, from Range: of Aperture’s Masters of Photography

Detail of 350 Mountains (with Smartphone Camera App Filters) for Aperture Spring Party Edition, 2015, from Range: of Aperture’s Masters of Photography

On Friday, April 17, Aperture Foundation will hold its first annual Spring Party. For this inaugural event, Aperture has teamed up with artist Penelope Umbrico to offer each party attendee a unique, signed photograph from Umbrico’s Moving Mountains series. Each print grants access to the Spring Party, which will feature an open bar, hors-d’oeuvres, music, and celebration. Umbrico, whose work has been shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1, New York, frequently engages with the saturation of images in a digitized word, sampling from catalogs, brochures, even Flickr. Online editor Alexandra Pechman asked Umbrico about the inspiration for the series, its recent presentation at Aperture’s gallery, and the changing world of contemporary photography. This article also appears in Issue 2 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Aperture Foundation: Your series Moving Mountains (1850–2012) began a few years ago when you were commissioned by Aperture to contribute to Aperture Remix, an exhibition for which photographers were invited to choose an Aperture publication and to pay it artistic homage. Why did you choose the Aperture Masters of Photography Series?

PU: I was interested in a converging the two most disparate things, the stability of a masterly photographic practice with the instability of smartphone camera technology.

AF: What attracted you to the mountain photographs within those books?

PU: I had been suddenly seeing images of mountains everywhere (on magazine covers, in galleries, advertisements, etc.), and thinking about the mountain as a symbol of stability, I had a quasi-theory that the more unstable our definitions of photography are, the more images of mountains appear in the photographs of photographers who have something at stake in the medium. So I looked for mountains in the Masters‘ photographs. I liked the parallel relationship of stable object to master photographer: the sense of integrity, history, and timelessness in both.

AF: You rephotographed the Masters photographs with an iPhone using various camera apps and their photo filters, rendering classic works by the likes of Edward Weston, Wynn Bullock, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Manuel Álvarez Bravo as almost entirely different images. What was your thought process behind this?

PU: If I was going to look at the mountains of master photographers, it made sense to rephotograph them with the least stable of photographic technologies—the smartphone camera app. I love that when the camera is pointing down at the books, the gravity sensor of the iPhone can flip a mountain sideways or upside down. This disorienting effect blends with hallucinogenic colors of the camera app filters, where photo grain, dot-screen, pixel, and screen resolution collide in undulating moirés. I was particularly interested in light-leak filters—nostalgic representations of the failures of analog photography, simulated with no light at all, in the vacuum of an iPhone.

AF: When first presented at Aperture Gallery, the photographs played off one another in a cohesive, colorful grid. Did you have an idea of how you wanted the images to look together or did the idea develop as you went along?

PU: I made about six thousand iPhone images in the course of a couple months. The fact that I could make so many, so quickly heightened the contrast between thinking about the inherent multiplicity of analog photography historically, and its limits in relation to current replication and distribution systems. The film/paper photograph becomes quite singular beside digital files and social media. I wanted the installation at Aperture to speak to this—I chose images from the six thousand-plus that would speak to each other as formally contingent parts of a whole. Not all the resulting images work this way: some work best in groups, and some are better on their own or in pairs.

AF: What was the most surprising thing you found going through the original images?

PU: The biggest surprise for me though was that, of the four women represented in the Masters of Photography series, none had images of mountains in their photographs. This solidified an idea about the symbolism of the mountain, and the fact that I, a present-day female, was rephotographing mountain images by male photographers only, by circumstance and not by choice, seemed to fit the symmetrically oppositional logic I had set up. I wrote a text piece that to accompany the work called Masters, Mountains, Ranges, and Rangers, —a progression through various dictionary definitions of those words that points to opposing ideas for each of those words, and questions their assumed cultural values. It’s in my e-book, Moving Mountains, which Aperture produced, and also in the new small book, Range (Aperture, 2014).

AF: Moving Mountains comments on the changing nature of contemporary photography, and was in fact, our first artist ebook when released in 2013 for the exhibition. Now the prints will be sold through Artsy online…and, of course, we’re previewing all this on a brand-new app! What does the pace of digital media today mean to you as an artist?

PU: It’s exciting for me because it’s my material, and therefore these changing technologies become my subject—the more there is, the more I have to work with!

AF: The purchase of one of the photographs gains entry to our first-ever Spring Party, which seems fitting for photographs that celebrate two centuries of photography. What do you hope the effect will be on those who live with this work?

PU: I’d like to think that the issues I address in a body of work are embedded in that work. For Range, (or Moving Mountains as it was called in for the first installation), the register of time, as you say, is quite literally in the work. But also each small piece contains a concentration of a dialogue between the old and the new, distance and proximity, limited and unlimited, the singular and the multiple, the fixed and the moving, the rare and the common, master and disciple, and the master and the copy.