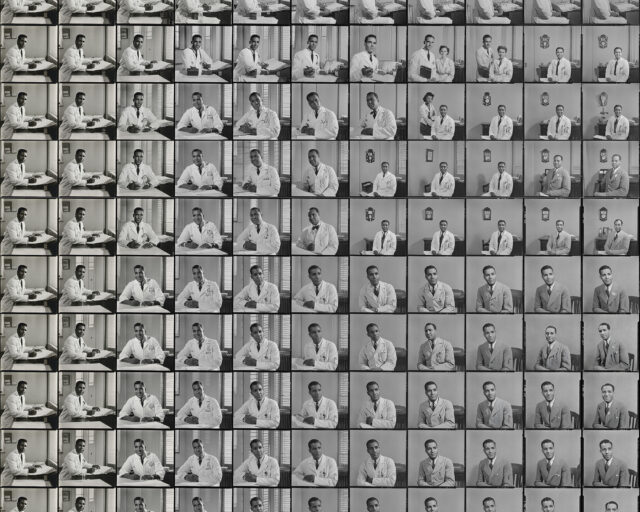

Napoleon Sarony, Oscar Wilde, 1882

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art and courtesy Art Resource, NY

Spirits, monkeys, and Oscar Wilde form a strange trinity. Close your eyes and you might imagine some fin de siècle late night in a smoky room, where a blindfolded Wilde excitedly channels spirit voices. Maybe a leashed macaque looks on skeptically. Surely absinthe is being consumed. I’m guessing, however, that the US Copyright Office’s regulatory guidance on generative artificial intelligence did not find its way into your vision.

Yet somehow this triad forms the doctrinal basis for one of the most impactful and controversial sets of rules that body has promulgated in years: its guidance on how and when it will grant copyright registrations for works (including photographs) containing material generated by artificial intelligence. Wherever you might come out on that charged moral and policy question—the Copyright Office, incredibly, received more than ten thousand comments in response to its public inquiry in 2023—surprisingly little has been said of the strange, almost mystical legal precedents that the Copyright Office has relied on to develop its current position.

At its core, the question is one of authorship, and it is constitutional. The same foundational text that gave us the separation of powers allows Congress to grant intellectual property protection to “authors.” For almost one hundred and fifty years, the Supreme Court has interpreted that weighty term to limit copyright to works that “owe their origin” to the mental conceptions of a person as opposed to the mechanical reproductions of a machine.

In a leading early case from 1884, the photographer Napoleon Sarony succeeded in asserting copyright in his 1882 portrait of Oscar Wilde—but only because the photograph evidenced Sarony’s “intellectual invention.” Sarony had, according to the court, posed “Wilde in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and . . . arranging the subject so as to present graceful outlines, arranging and disposing the light and shade, suggesting and evoking the desired expression.” The court was clear, however, that this was no “ordinary” photograph, which in the usual case (without Sarony’s aesthetic sense behind it) might have remained a purely mechanical process meriting no copyright protection. Copyright, in other words, must come from the photographer and not the camera.

Despite the many decades that have passed since the obsolescence of the glass-plate negative, the case continues to speak to many of the core issues in the AI copyrightability debate. Is generative AI, like Sarony’s camera, simply a tool in the service of an artist’s skill and vision—a brush or burin for the 2020s—or is it, instead, the creator?

This leads us to the Copyright Office’s current legal test, shaped in no small part by Sarony’s precedent. When an applicant seeks to register a work containing some AI-generated material, the applicant must disclose which aspects were contributed by humans and which were not. The examiner will then decide whether the work is “basically one of human authorship, with the computer . . . merely being an assisting instrument, or whether the traditional elements of authorship in the work . . . were actually conceived and executed not by man but by a machine.’’ If the former, the Copyright Office will grant a copyright; if the latter, the work will be in the public domain for anyone to copy for any purpose.

When we call AI a black box, how different is that really from assigning agency to a spirit or the occult?

Sarony’s case is not the only precedent shaping this test. And that is where things start to get stranger. In justifying its current rules, the Copyright Office has also repeatedly pointed to a series of twentieth-century precedents involving claims over works created neither by man nor machine but by divine spirits. The leading citation here is Urantia Foundation v. Maaherra, an enigmatic case from the 1990s in which both the copyright claimant and the defendant agreed that The Urantia Book—a two-thousand-page religious text that emerged in the early twentieth century—had been written by “non-human spiritual beings” including “the Divine Counselor, the Chief of the Corps of Superuniverse Personalities, and the Chief of the Archangels of Nebadon.” Despite this spiritual baggage, the court recognized a valid copyright. While the teachings may have been divine, the court observed, a group of human interlocutors prompted the spirits to reveal those lessons and arranged the answers in a minimally creative way.

The Urantia court opinion pointed to a contrary holding from the 1940s in which the copyright claimant characterized himself as merely the amanuensis to whom a text was dictated by “Phylos, the Thibetan, a spirit.” That copyright assertion, unlike the one in Urantia, was rejected because the human scribe had claimed protection in the divine revelations themselves as opposed to any human arrangement of them. You can prompt the cosmos and remain a copyright author, it would seem, but straight transcription damns the work for all eternity.

© the artist and courtesy Caters Media Group

Better known than Urantia, but equally esoteric in its facts, is Naruto v. Slater, a litigation literally brought by a seven-year-old crested macaque against the wildlife photographer David Slater. Naruto the monkey, who had taken a few selfies with a camera left around by Slater, naturally took umbrage at seeing copies of his work reproduced without permission and saw fit (with a little help from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) to sue Slater for copyright infringement. Suffice it to say, the monkey’s case was thrown out of federal court because copyright infringement remains a claim viable only to humans.

To be clear, these are not incidental, one-off citations by the Copyright Office. The government relied on Urantian revelations to support its position on AI-generated content in, for instance, its official statement of policy in its formal federal regulations, every one of its four published registration decisions in the AI section of its website, its official compendium of registration practices, its recent extended report on Copyright and AI, and its extensive appellate briefing on the leading case in this area, Thaler v. Perlmutter.

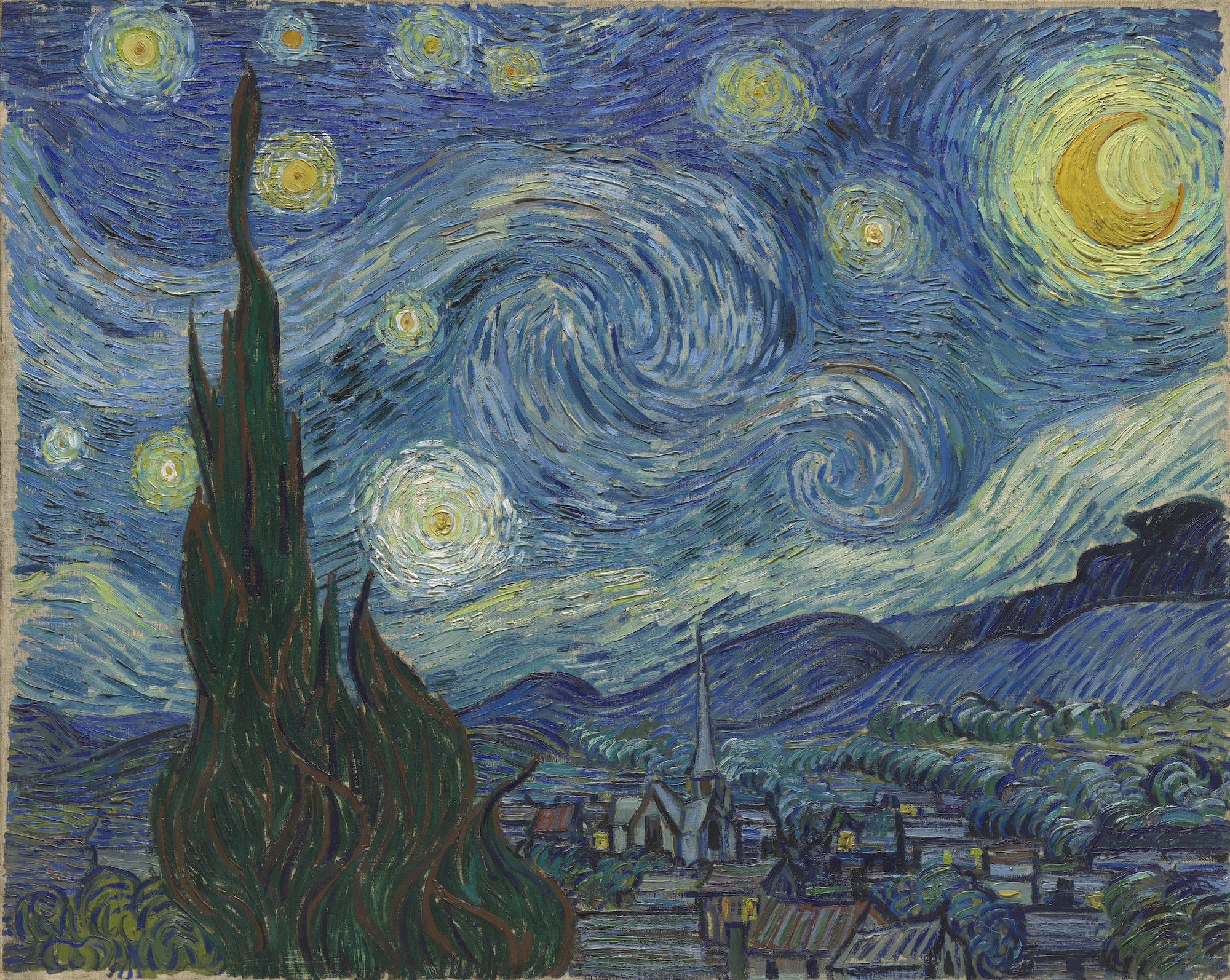

At this point, you may be wondering how exactly the Copyright Office is applying these extraordinary precedents to everyday copyright claims in the AI space. Take as an example the recent attempt by Ankit Sahni to register SURYAST (ca. 2021), a work that was essentially a mash-up of a source photograph taken by Sahni of a sunset with Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889). Sahni inputted into an AI-powered tool known as RAGHAV a base image (his original sunset photograph), a style image (The Starry Night, which is in the public domain), and a value to determine the strength of the style transfer for the tool to use. RAGHAV then generated the final work without, we are told, further modification or input from Sahni.

The Copyright Office rejected the application. Despite the fact that the source photograph was taken by Sahni (and likely copyrightable on its own), it concluded that “the RAGHAV app, not Mr. Sahni, was responsible for determining how to interpolate the base and style images in accordance with the style transfer value. The fact that the Work contains sunset, clouds, and a building are the result of using an AI tool.” On what legal authority? It turned, naturally, to our cases on Oscar Wilde, the chief of the archangels of Nebadon, and a crested macaque.

© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

What should we make of the fact that in setting critical policies for a truly paradigm-shifting technology, the Copyright Office is comparing generative artificial intelligence to a nineteenth-century albumen-silver print, revelatory channeling, and monkey selfies? Analogic legal reasoning, the core process by which common law develops through the selection and analysis of like precedents, inevitably involves some leaps. The rules governing digital music distribution were derived from cases on flea markets, the Sony Betamax, and the player piano before that.

We will naturally see this methodology at work soon as US courts start deciding the so-called ingestion photography cases (the negative, if you will, of the copyright registration authorship debate described above). Take, for instance, the photographer Jingna Zhang’s 2024 suit against Google, now consolidated into an even larger litigation, accusing the company of directly copying her photographs, without permission, for use in training Google’s Imagen text-to-image diffusion model. Or look to the recently refiled version of the case Getty Images v. Stability AI, in which Getty has accused Stability AI of not only copying twelve million Getty images to train its original Stable Diffusion model but allowing for the regeneration (in a somewhat grotesque form) of modified versions of those images as outputs.

Barring any settlement, both claims are likely to hinge on the fair use defense, with key precedents ranging from Lynn Goldsmith’s victory over the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts in 2023 to Google’s own successful assertion of fair use in defense of its Google Books initiative ten years ago. As we have seen in a handful of issued opinions this summer in AI cases involving the ingestion of books, these suits might turn on a simple choice between two metaphors: Is ingesting countless copyright-protected photographs into a dataset, and using that set to train Imagen or Stable Diffusion, more like the Warhol Foundation’s commercialization of unlicensed derivative illustrations to compete in the same market as Goldsmith’s original artist reference photograph (not fair use), or more like the volume scanning of every book ever to create a searchable corpus of the world’s literature (fair use)?

Still, there needs to be a core logic to any legal metaphor, particularly when the stakes are as high as they are: a technology poised to overtake so much creation. We can intuit why a court in these ingestion cases might compare the training of text-to-image AI software to either using a photograph without permission to create competing works or to the digitization of millions of books.

But the Copyright Office precedents on copyright authorship look to far more distant realms. Although the otherwise staid body would certainly deny it, there is something bordering on mystical in the government’s position. By relying on supernatural precedents, it is inherently assigning a spiritual ineffability to the AI-generative process. It is effectively stating that when photographers upload a source image to a generative AI program such as Midjourney, they are closer to animal or medium than artist.

Not that this mysticism is necessarily unfounded. Almost every thoughtful account of generative artificial intelligence concedes, at a certain point, that its own developers really cannot explain or account for any given output from the tool. When we call AI a black box, how different is that really from assigning agency to a spirit or the occult? Aren’t we effectively attributing authorship to the ghost in the machine either way? The human is merely prompting the unknown in both cases, in every sense of that verb.

Andrew Ventimiglia, the author of an exemplary study of the Urantia cases, pushes the analogy even further, arguing that such precedents show how the physical objects of intellectual property—the hard-copy Urantia Book or Naruto’s, Sarony’s, or Sahni’s photographs—themselves “assert a kind of ghostly ontology.” That is, they are imbued by virtue of their litigation histories with the aura and spirit of law and the almost supernatural threat of copyright enforcement should one reproduce them.

However compelling these metaphysical analogies, though, copyright policy has real consequences on the ground. Whether and how we grant century-long monopolies in content has tangible stakes for countless people (including the many photographers reading this) and entire industries. It seems borderline absurd that we would build such monumental AI policy choices on a foundation of arcane precedents adjudicating the copyrightability of the aesthetics of Victorian photography, divine revelations, and the standing of monkeys.

I don’t mean to suggest that the Copyright Office has acted improperly here. That body is not empowered simply to create new rules out of whole cloth. It can only weave together the collection of opinions it has been handed by the federal courts, however crazy a quilt might result.

What this instead reveals is another limitation of the slow, rear-facing, and too-often nonrational development of our copyright doctrine. Confronted with a groundbreaking technology our copyright administrators are left divining old, mystic texts rather than asking straightforwardly what the best rule would be to incentivize some desirable outcome.

All that said, it remains fair to request, at the very least, that the Copyright Office shape its guidance on generative AI with a view more toward this world than the next.

A version of this article originally appeared in Aperture No. 257 “Image Worlds to Come: Photography & AI.”