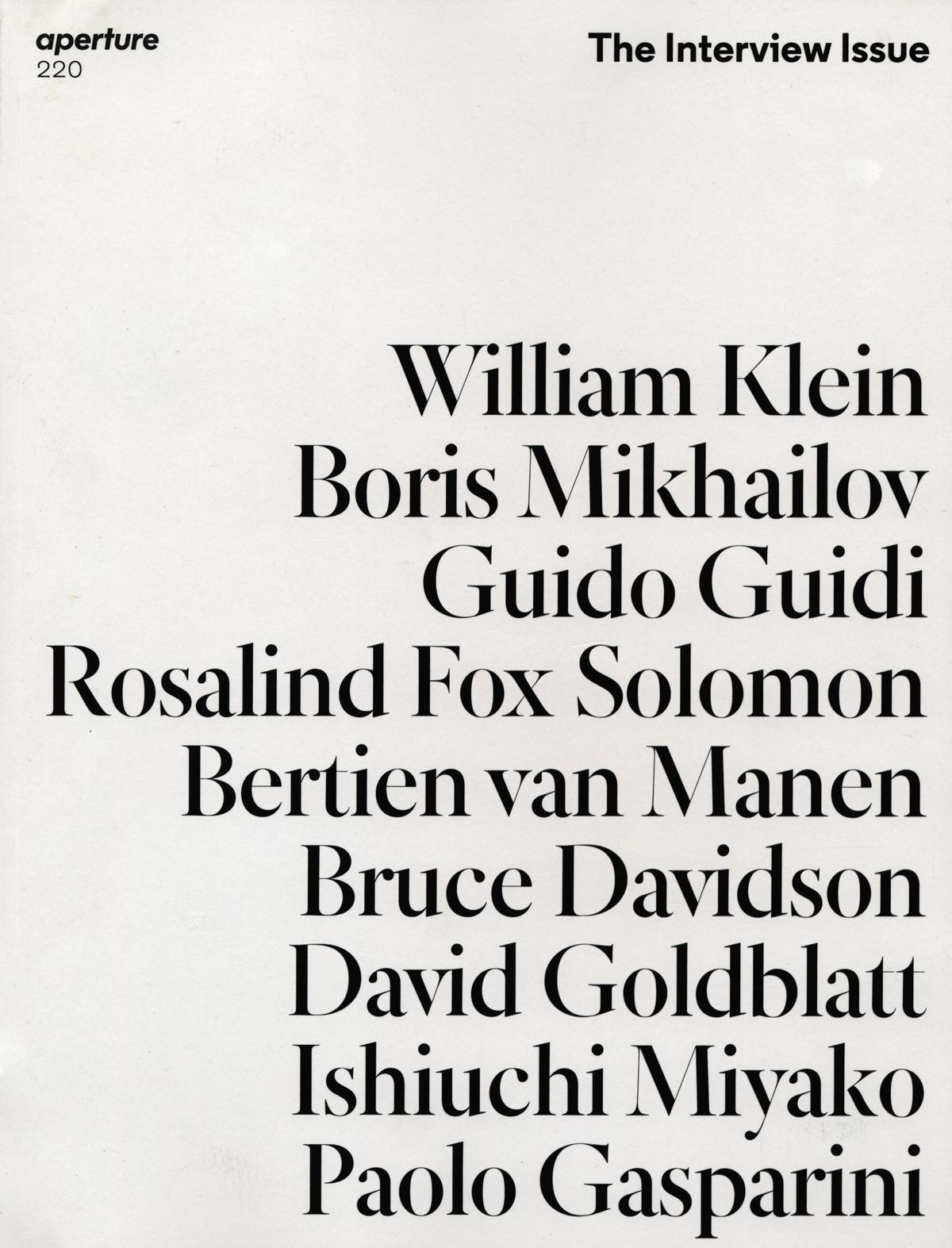

Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue”

What compels someone to become a photographer? And what drives someone to continue to be one, for as many as seven decades? How does a veteran photographer describe years of questioning politics, personal experience, social unrest, landscape, and history through the camera?

For this issue we have broken with our usual “Words” and “Pictures” format to offer nine in-depth interviews, firsthand accounts that underscore the generosity and intelligence of their speakers. Born between 1928 and 1947, the nine photographers here—Bruce Davidson, Paolo Gasparini, David Goldblatt, Guido Guidi, Ishiuchi Miyako, William Klein, Bertien van Manen, Boris Mikhailov, and Rosalind Fox Solomon—are still active today, adding to their already unparalleled bodies of work. In these pages, the medium is considered from various points of view, offering a range of philosophies, values, and perspectives, yet for all the differences within this group, they share a fundamental curiosity about the human experience.

The interviews took place around the globe, and five of the nine were conducted in languages other than English, in the photographers’ native tongues: Japanese, Russian, Italian, Spanish, and Dutch. No matter the language, an underlying passion and drive come through in the force of each speaker’s words. William Klein, for example, now eighty-seven, is sharp-witted and voluble; his anecdotes project ecstatically. No surprise, then, that we learn through the course of his conversation with writer Aaron Schuman that Klein had been out until very late the previous evening at filmmaker David Lynch’s club in Paris.

That kind of restlessness characterizes each speaker. Solomon and van Manen are both peripatetic, having traveled throughout the world to focus on questions of community, ritual, place, and gender identity. Guidi, known for his understated images of European towns, meditates on how the mechanics of images, specifically perspective, allow for a description of the world—a world that is often politically fraught. Goldblatt has long used the camera to reflect the social realities of apartheid and postapartheid South Africa. For Gasparini, who has documented social conditions in his adopted city of Caracas, postrevolutionary fervor in Cuba, and experiments in architecture across Central and South America, photography cannot be split from ideology. Empathy for others has likewise motivated Bruce Davidson, who remarks that the joy of photographing, and returning to former subjects, sustains him. Ishiuchi was a reluctant photographer at first, but succumbed to the physical presence of pictures and their ability to trace history and time, from the personal (her relationship to her mother) to history on an incomprehensible scale (the bombing of Hiroshima).

These lifetimes of seeing through the lens might best be summed up by Boris Mikhailov, who made much of his work under oppressive Soviet rule. “When you’re open to life, it responds to you,” he remarks. “That is what an intuitive possibility of photography is—to crawl deeper into the depths of life.”

—The Editors

The following note first appeared in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue.”