Interview with Laura Letinsky

The photographer Laura Letinsky has explored the expressive possibilities of still-life photography for fifteen years. A survey of these photographs is on view at the Denver Art Museum through March 24, while a selection of images from her most recent series, “Ill Form and Void Full,” is being presented at the Photographers’ Gallery in London through April 7. Brian Sholis spoke with Letinsky about genres, cannibalizing one’s own work, and bodily intelligence.

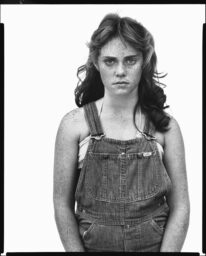

Untitled #54 from the series Hardly More Than Ever, 2002 © Laura Letinsky

Brian Sholis: How did you shift from your early photographs of people to the still lifes for which you are now best known?

Laura Letinsky: For a long time I’ve asked myself questions about what a photograph is. While I was taking photographs of couples in the 1990s I began thinking about love, and about how photography relates to love, how it can functions within a kind of circuitry of production and consumption. We produce photos that show us what love is supposed to look like, then we enact in our everyday lives the conventions depicted in visual media. I wanted to break out of that cycle, and to break out of the conventions of the genre in which I was working. I love portrait photographers like Philip-Lorca diCorcia and Rineke Dijkstra, but I felt stifled by the inescapability of romance. I also wanted to switch from an omnipotent point of view to something that felt more immediate, more first-person.

Still lifes increasingly drew my interest. It interests me as a genre in the same way that concepts of love interest me—its association with the feminine, its characterization as “less important,” its affiliations with domesticity and intimacy. There seemed to be potential there, room for exploration. I realized that still lifes were a vehicle to explore the tension between the small and minute and larger social structures. For the last fifteen years I’ve explored this realm, increasingly weaving in questions about perception, about how we see and understand the world around us, and about how photography conflicts with and constrains our sense of our environment by reinforcing certain ideas we have about perception.

Untitled #49 from the series Hardly More Than Ever, 2002. © Laura Letinsky

BJS: You’ve spoken in the past about your interest in the corporeal aspects of your subjects, the inference of a bodily presence. In your most recent still lifes you’ve introduced your own previous work. How does this “cannibalism”—the consumption of a “body” of work—build upon this notion?

Untitled #31 from the series Ill Form & Void Full, 2011 © Laura Letinsky

LL: I do like the idea of ingestion and consumption and photography. You could say that my work is in part about the relationship between looking at something and other bodily experiences. Pictures can induce sensations: You can see something in a photograph and it might make your mouth water, or it might stimulate other wants, desires, regrets, or needs.

Using images already in the world, including my own earlier works, is akin to using objects in the world. It’s all raw material ripe for the picking, so to speak. Alongside its ability to provoke sensations, photography has a way of homogenizing experience. A piece of schmutz and a Tiffany diamond become the same thing once they’re photographed—they become photographs. I have a love/hate relationship with this power of the camera to flatten difference.

Subjecting my own work to this process, whether old test prints or reproductions from books—makes all images, anything and everything, fair game from which to cull. And images are promiscuous; they are everywhere, and they don’t care what we do with them, or how they circulate.

BJS: And yet you’re very careful about the scale and presentation of your work …

LL: I am very invested in printing my work at a certain scale and in not having glazing between the photograph and the viewer—I want to offer a sense of proximity and the experience of the picture’s materiality. This new work especially called for this treatment. When I’m making pictures, I try to deal with the demands of the picture, what it needs to get my idea across. It’s a question of form and content, not one or the other. I’ve become much more freewheeling about how to satisfy this question. I draw from, dare I say, intuition as well as the huge image world—including scanning or downloading objects and images to insert into my photographs. What’s the difference? They all end up as a picture.

Untitled, 2011. From the series Ill Form and Void Full. © Laura Letinsky. Courtesy of the artist and The Photographers’ Gallery, London

Untitled #18, 2011. From the series Ill Form and Void Full. © Laura Letinsky. Courtesy of the artist and The Photographers’ Gallery, London

This new process has manifested itself as a way of dealing with the slurry of images. I have two or three tables in the studio laden with piles of objects and images. Sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly, groupings emerge. Once I’ve found a way to begin an arrangement, I often have to wait for the light to be right, or I have to pull parts out and rearrange until the picture reaches the level of precariousness that feels right. I wanted to be a painter when I first began making art, and now I work in a manner similar to how I imagine painters work in their studios.

BJS: Despite your description of accumulations in the studio, your pictures have a remarkable visual economy. Can you speak about how you determine what’s necessary to depict versus what’s unnecessary and therefore left out?

LL: I want to keep the images on a precipice but it’s not one I can easily explain with words. Artists are increasingly encouraged to be able to explain their working processes, and yet it’s a nonverbal intelligence that often leads you to make a decision.

I teach at the University of Chicago, and when a colleague was going through the tenure process she described one aspect of her work using the word “intuition.” She made no excuses for it, and did not try to explain that aspect of her artwork further. And she was right to do that. Some of the decisions I make in the studio are very conscious, and I use words to think about them. But when I make pictures I also do a lot of “grunting”—“ooh”s and expletives included; I use a kind of visual thinking that just can’t be articulated. Morandi paintings, for example, resist textual description. I love them but it’s difficult to explain why. Maybe it’s like love—try explaining why you love someone. It defies such definition. Some might say it’s emotional, but I think of it as bodily—or rather, that the body and the mind are inseparable. The body does have intelligence.

How can you legitimize the body’s intelligence? Think of people with refined palates, or designers who consistently make pitch-perfect decisions. It is in this realm that a lot of pleasure and discomfort resides. It’s an important component of the experience of art, and one that is often left behind in today’s overly intellectualized, airless conversations around art. The sensation of my child’s body, or the experience of food, sex, or pain—photography can help access these feelings that are intrinsic to being human.

—

Brian Sholis is a member of the editorial staff of Aperture Foundation. He writes frequently on photography, landscapes, and American history.