Introducing: Luther Konadu

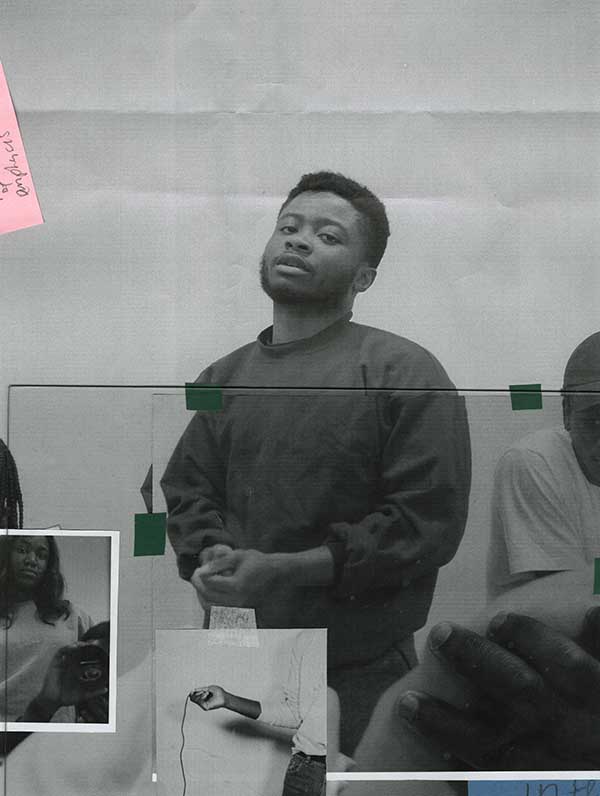

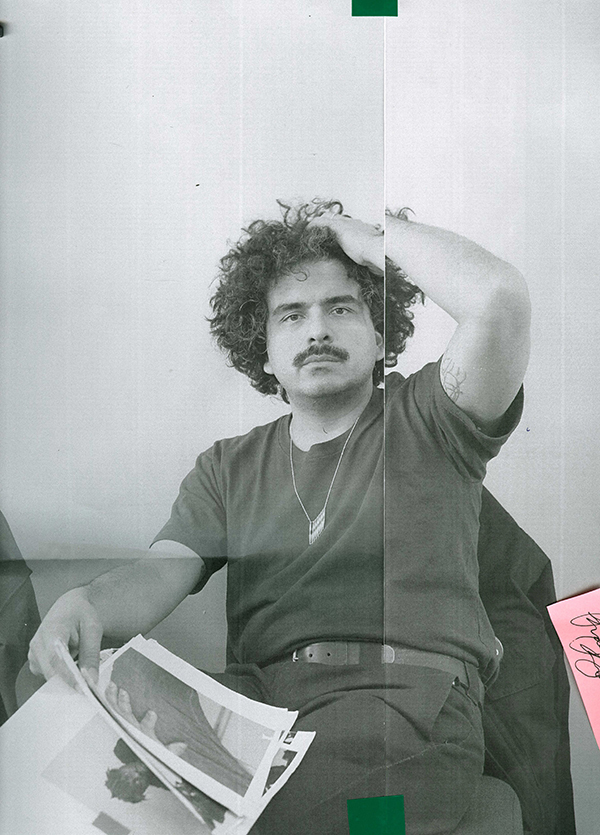

He had me at the green tape. One morning I was on the subway reading a magazine when I flipped to a page with a portrait of a man with curly hair. The man had a tattoo on one of his biceps and a rakish mustache. He held in his hands a sheaf of photocopies, and the portrait itself looked like a photocopy, but one that was assembled into a grid with tape, Kelly green and slightly uneven. On the edge there was a pink Post-It, attached with the casual elegance of a well-placed accessory. Before I saw the credit line, I knew who had taken this picture. The magazine was the New Yorker. The subject was the musician Helado Negro. The photographer was Luther Konadu.

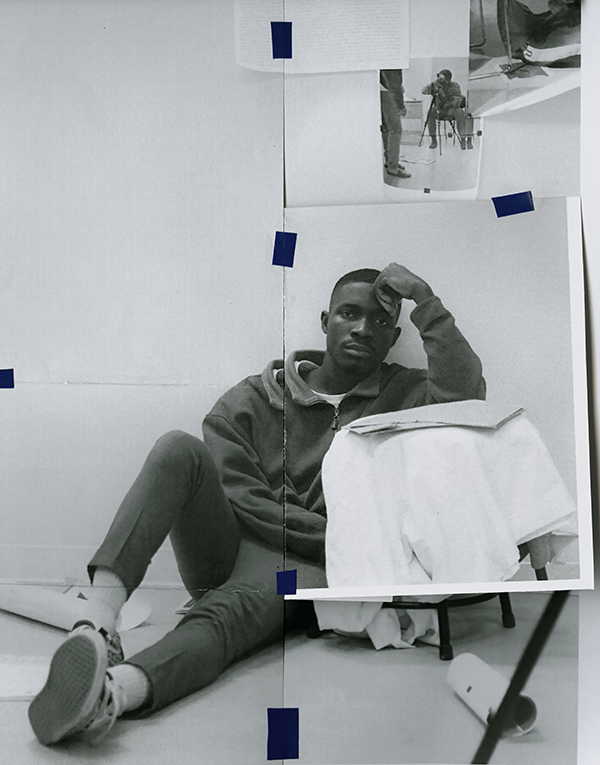

Although he says he hasn’t had any training in photography, Konadu knows how to take a picture. Like other subjects of Konadu’s personal work—mostly young and black, friends or friends of friends—Helado Negro, the recording name for Roberto Carlos Lange, gazes out from Konadu’s portrait with a kind of inquisitive confidence. He could be Konadu’s friend, even though, at the time the picture was made, the two had just met. “Luther’s photography appears casual,” the critic Antwaun Sargent told me, noting that Konadu’s process recalls the work of Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, and Paul Mpagi Sepuya. “But linger on his images and what is recognizable is their precise and thoughtful construction.”

Konadu was born in Ontario to Ghanaian parents. When he was 23, he moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, where he has a studio practice and runs the online publication Public Parking. He’s also a writer-in-residence for Gallery 44, a photography space in Toronto. In April 2019, he won a New Generation Photography Award from the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. One of the prize jurors, Deanna Pizzitelli, noted Konadu’s “keen sense of design” and the way his images seem to “reinvent” his subjects. “In his work, we experience narrative as something unfixed and unfolding,” Pizzitelli wrote, “one that includes text, fragmentation, and re-photography.”

Coralie Kraft, a photo editor at the New Yorker who commissioned the portrait of Helado Negro, was also drawn to Konadu’s use of re-photography—and to the tape. “We are so quick to look at someone and put them in a box, whether they’re your colleagues, friends, or family,” she says. “But tape can be removed or swapped.” Personal identity is mutable; often, as Konadu shows, identity is a construction of groups, of the people around us, all of these elements cut and folded and pasted together. Helado Negro was born in Florida to Ecuadorian immigrant parents and Kraft wanted a portrait that spoke to the interlayering of self and society. “We specifically had Luther play with the physicality of the image,” she says.

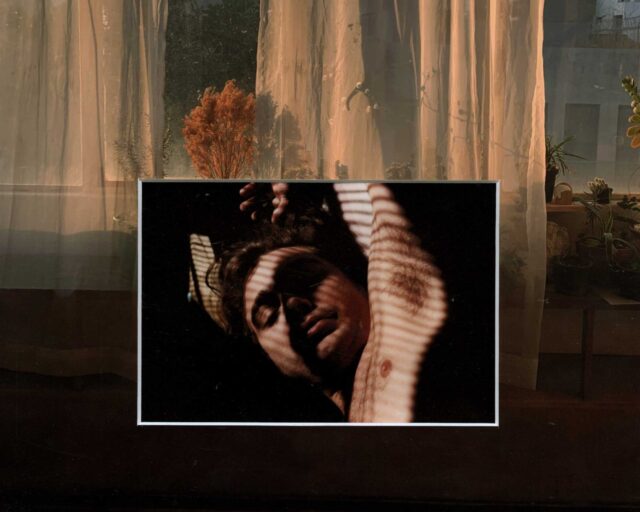

Photo illustration for the New Yorker

When it comes to his influences, Konadu wears his heart on his sleeve. His pictures have the intensity and introspection of Weems’s portraiture and Sepuya’s mirrored choreography of camera and studio. But there’s also those folded and unfolded aerogram-prints by Moyra Davey, with their firm green squares of tape. There’s Andrzej Steinbach’s multipanel cast of characters. There’s LaToya Ruby Frazier’s documentary work that sometimes melds with performance. “I’m interested in taking off from what they’ve begun and seeing what I can contribute to it,” says Konadu. And as for the photograph itself? “I’m always trying to make a photograph look more like a photograph, an object, as opposed to a portal into the realities of those who appear in my images.” Making the surface more “haptic”—more tactile—is a means to “snap viewers out of the illusion of representation” and to create a tension between the real and the fictional. Scanning copies likewise creates a “veil,” as Konadu calls it. “I essentially want viewers to second-guess what they’re looking at.”

Konadu had been a fan of Helado Negro’s music before he took the singer’s portrait. There’s one song he likes, “2º Dia,” that he listened to on repeat. And even though he doesn’t speak the language—the song is entirely in Spanish—“I’m there with him. I can somehow empathize and connect.” Konadu says his editorial work might be a space to “extend the family,” to continue his interest in the collectives and identities of Indigenous, black, and queer subjects. That family is full of gazes, sometimes questioning, sometimes just hanging out and working through things. Antwaun Sargent added that he admires Konadu’s physical approach to photographs, which, he says, heighten an exploration of power and agency. “His subjects,” notes Sargent, “are looked at, but they look back, too.”

All works courtesy the artist.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.