Kaveh Kazemi, Defiant Revolutionary, 1979

February 2019 marked the fortieth anniversary of the Iranian Revolution. The last major revolution of the twentieth century, which toppled an ancient monarchical system and ushered in an Islamic theocracy was a widely photographed event. By the time of the revolution in 1979, Iranians had been exposed to photography for more than a hundred years; it wasn’t uncommon for ordinary middle-class people to own cameras. A professional cadre of photojournalists followed the royal court and the country’s growing pop-culture personalities, providing news photographs for the daily newspapers and numerous weekly magazines. But it was the revolution, followed by the American hostage-taking, and then the eight-year war with Iraq, that propelled Iranian photographers into new territories, transforming them into serious practitioners of new genres.

Photographs of the first year of the revolution helped fix the inevitability of a new Iran in the eyes of the world and the psyche of the Iranian nation: the crying Shah leaving the country as one of his officers threw himself at his feet, Ayatollah Khomeini descending the steps of the Air France chartered aircraft that carried him back to Tehran, executed generals’ and ministers’ corpses lying naked on mortuary slabs, published daily in newspapers. For all Iranians there must be a number of images that mark for them the progress and development of the revolution. For me, these photographs are searing reminders of the nascent days of the new regime and the blossoming of Iranian photojournalism.

Courtesy Getty Images

Two photographers whose careers changed because of the revolution were Maryam Zandi and Bahman Jalali. They were both young amateur photography enthusiasts who had secured jobs as in-house photographers in National Iranian Radio and Television, which published its own magazine.

Monday, December 11, 1978, was the day of Ashura, the second of two consecutive holy days of mourning in Iran, when processions of black-clad men take over the street to mark the martyrdom of Imam Hussein by flagellating themselves with chains to the sounds of beating drums. The revolutionaries, well aware of the immense symbolism of these days, had arranged a large demonstration.

Iranian Radio and Television had called a strike in sympathy with the anti-Shah demonstrators. Zandi was at home when she heard about the big protest march. She felt these strange new times had to be recorded, but there was no one to look after her two-year-old daughter. So she threw her camera bag on her shoulder, and her baby girl on her hip, and headed out into the street.

Crowds already filled the streets and the square around Tehran University, punching their fists in the air, shouting slogans against the Shah and dictatorship. Zandi decided to climb upon a bus shelter to get a better view, but couldn’t do so while holding her daughter in her arms. So she asked a woman standing nearby if she would hold her child for a little while. “On one condition,” said the woman. “If you shout ‘long live Khomeini.’” Zandi passed the child into the stranger’s arms and yelled: “Of course, long live Khomeini!” as she climbed atop the shelter. She doesn’t remember how long she stayed there, but she does remember being scared when she saw the crowd from above. She had never seen so many people in one place.

© and courtesy Rana Javadi

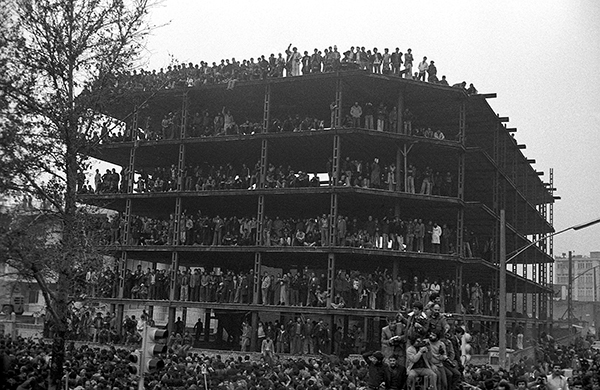

Numerous photographs of the Ashura demonstrations show the multitudes marching with their banners. But one of the most memorable images of that day depicts a half-finished five-story building overrun by onlookers seeking the perfect vantage point. Filling every floor, men and women flesh out the spaces where walls should have been. Taken by Bahman Jalali, the image of a half-finished building close to the Azadi monument suggests a striking metaphor: the country’s incomplete project of modernity imagined by the Shah, interrupted by tiers of people, hopeful, excited with merely a skeletal idea of what they want. None of them knows how this half-finished structure will look when the project is complete.

Bahman Jalali wasn’t a photographer by training. Before the revolution, he had studied politics and economics at Tehran University. He traveled with the architecture students on their many road trips around Iran, taking photos of traditional houses. When the unrest began in 1978, he and his wife, Rana Javadi, who had picked up the photography bug from him, joined the throngs in the streets to photograph the events. She could move freely among the women and provided a different point of view.

Jalali, who went on to establish Iran’s first university course in social documentary photography, may have sensed the uncertain nature of the revolution; in another photograph that resonates deeply with many Iranians who, four decades after the event, are questioning the outcome of their revolutionary actions, he shows a young man waving a banner atop a traffic sign that reads “Choose your direction before you reach the bridge.”

Another couple were also busy recording the events in the streets of Tehran in those days: Kaveh Golestan, the son of one of Iran’s celebrated film directors, Ebrahim Golestan, and his wife, Hengameh. At the outbreak of the revolution, Kaveh Golestan had already established himself as a photographer with a talent for accessing challenging social documentary subjects, such as the sex workers of Tehran’s red light district. With Hengameh at his side, he photographed the scenes of bloody conflict, while she focused her camera on the women.

By January 1979, the Shah was forced to leave. The photographs of his unceremonious departure were captured solely by Iranian photographers, according to Jafar Daniali, who worked as a staff photographer for the daily newspaper Ettela’at. As he recalled in an interview with an Iranian publication, he and a handful of his colleagues managed to get past the guards and into Mehrabad airport, while two busloads of foreign journalists were held back because the Shah did not want the foreign press there.

Daniali, who had made his way under the plane’s stairs, describes how weak the Shah’s legs appeared, and how he heard him groaning as he boarded the plane to leave the country and end a 2,500-year-old monarchy. The various photographs of his departure were circulated widely around the world, paving the way for the next stage of the revolution: the return of Ayatollah Khomeini from his fifteen-year exile, first in Iraq and then briefly in France. A cleric and critic of the Shah, he arrived back in Iran aboard an Air France–chartered plane in a posse of his followers.

The numerous photographs of his descent from the airplane mark what Iran’s Islamic government refers to as the “succession of the revolution.” The image has such iconic value that in recent years, a two-dimensional reenactment of the famous descent has become a regular feature of the celebrations: soldiers carry a cardboard cutout of Khomeini down the steps of a plane, creating a somewhat flat, if not altogether bizarre, tribute.

Courtesy Magnum Photos

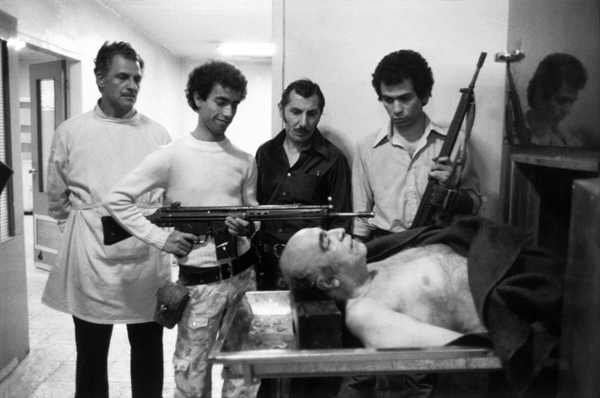

The late Abbas Attar, a longtime member of Magnum Photos, had left Iran at an early age, but he visited the country both before and during the revolution as an established international photojournalist. Of all his images of the revolution, his photograph of Amir-Abbas Hoveyda, Iran’s prime minister from 1965 to 1977, in a morgue might be the most unnerving. Hoveyda, who was famous for wearing an orchid in his buttonhole and smoking a pipe, did not leave the country when the Shah left. He gave himself up to the revolutionaries because he felt he had not committed any wrong.

Like many of the Shah’s generals and high-ranking officials, he was judged as “corrupt on earth” and executed by the revolution’s merciless hanging judge Sadegh Khalkhali, who had a penchant for five-minute trials and executions in makeshift situations. Hoveyda was apparently shot dead during the recess in his trial in the basement of Qasr prison. It has been suggested that his corpse was returned to his chair for the reading of his verdict. Abbas’s unsettling photograph of the morgue shows Hoveyda surrounded by four men, two of them posing with their assault weapons (which were not used in his execution) with triumphant smirks. The composition echoes the photograph of the dead Che Guevara, positioned so gleeful men with rifles could record themselves in a macabre memento mori.

Courtesy the Artist

Iranian women were an intrinsic part of the Iranian Revolution. They would become its icon. A photograph by Kaveh Kazemi—one of the only academically trained photographers of the revolution, who had trained in the UK in the seventies—shows a militiawoman holding her hand out of the impenetrable blackness of her chador, while brandishing a G3 weapon. The towering chador, apart from being an immensely powerful image in its own right, heralds what is to come in the Islamic hegemony that will be forced on the country, as well as how it will be represented visually for decades afterward. The Iranian black chador, worn by the pious and political, became a favorite of visiting photographers depicting the revolutionary spirit of Iran.

On March 8, 1979, less than a month after the succession of the revolution, Iranian feminists chose International Women’s Day to demonstrate against enforced veiling. Joined by the American feminist Kate Millett, who had come to Iran inspired by the role of the women in the revolution, they braved heavy snow in the streets of the capital,to show their dismay at Ayatollah Khomeini’s announcement that the wearing of hijab would be required of all women in Iran.

Their hopes of greater equality and freedom after the revolution were dashed by this fundamentalist slogan during the march: “Ya roosari ya toosari”—wear a scarf or be smacked on the head. The photographs of this march are an exotic reminder, for the younger generation who grew up with mandatory rules of modesty, that compulsory veiling was not accepted without a fight by secular Iranian women.

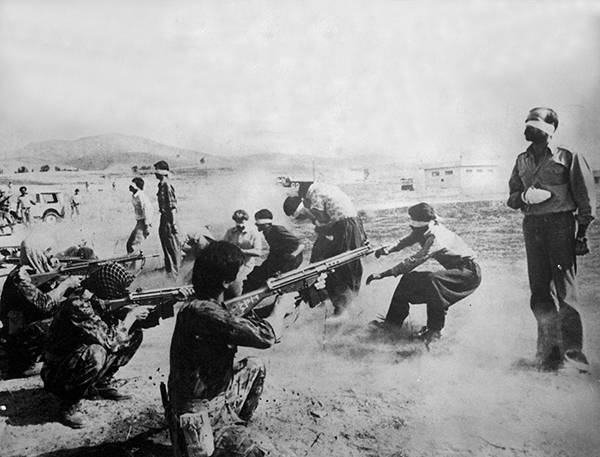

The early days of the revolution saw power struggles between the various revolutionary factions in Tehran. There were also serious incidences of ethnic unrest in other areas of the country. In August 1979, dissenting Kurds in the northwest of the country were punished with impunity. Some of the captured rebels were taken to Sanandaj Airport to meet their fate in one of Khalkhali’s notorious courts.

A series of images captures the execution of eleven men who are shot dead by a firing squad in Sanandaj airport. The photographer even records the point-blank shots that ensure the men are dead once they hit the ground. But the most powerful image, known as Firing Squad in Iran, shows the men in various stages of being hit by bullets: some are already on the ground, others bent double by the force of the bullet entering their body. This photo was distributed by United Press International without crediting the photographer, and became the recipient of the only anonymous Pulitzer Prize ever awarded in Spot News Photography in 1980. No one knew the photographer’s identity until 2006, when the Wall Street Journal revealed the photographer to be Jahangir Razmi from Ettela’at newspaper. Razmi’s editor in Tehran had decided at the time that his identity should remain secret for his own safety during the vengeful early days of the revolution.

Courtesy United Press International

On November 4, 1979, another event affected the growth of homegrown photojournalism. A group of hardline students supporting Ayatollah Khomeini climbed over the walls of the U.S. embassy compound in Tehran and took fifty-two American diplomats and citizens hostage for 444 days. They paraded the hostages, blindfolded, with arms tied, to be photographed by the international press. This was an opportunity for the regime to use visual media to convey its independence from the West—specifically, its anger toward the United States (already deemed “the Great Satan”), which had propped up the Shah.

One such image, of a man—a hostage—in a white shirt, with a thick white blindfold wrapped in layer after layer around his head, as if he is readied for execution, became the emblem for the US television show Nightline, a program hosted by Ted Koppel and created specifically to follow the state of the hostage crisis. These photographs would form an image of Iran as barbaric and hostile in the minds of American viewers, which to this day has proven difficult to erase.

After the hostage-taking, many foreign journalists, including Michel Setboun, who had come to Iran early on to record the revolution, decided to leave. They handed over the job of covering the still-volatile country to local photographers, who stepped in to supply the foreign media with the images they needed. Setboun passed his SIPA mantle to Reza Deghati, whom he connected to the agency. “There were these young Iranian photographers that grew up with us. It was time to let them take over. They could speak the language; all they needed was a connection to the outside media, which they didn’t have before,” he says. With that, Iranian photojournalism took another step forward. The hostage-taking was not only good for Iranian local photographers; it was also one of the first landmark events that consolidated the hold of the Islamists on the way the country would proceed. Iran’s foreign policy took an irreversible turn into isolationism and belligerence toward the world.

By 1980, the eight-year war with neighboring Iraq had begun, providing Iranian photographers with a chance to experience war photography, and allowing the new Islamic government to tighten its grip on internal politics with the sophisticated use of photography as one of the sharpest tools in their propaganda toolbox.

Four decades on, photographers like Maryam Zandi and Kaveh Kazemi have been given rare permits to publish photobooks of their images of the days of the revolution. According to their publisher, the younger generation of Iranians are very interested in images that depict that cusp in their history. The treasury of photographs by these local photojournalists provides them with a chance to review their history independently from the official narrative and provide a fuller picture of those turbulent days.