Archipelago

Across ten years, Ishikawa Naoki traveled Japan’s island chains, from the far south to the far north, depicting canted colorful scenes of everyday life and ceremonial traditions. This article is drawn from the recent “Odyssey” issue of Aperture magazine.

All photographs by Ishikawa Naoki from the series Archipelago, 2009 © and courtesy the artist

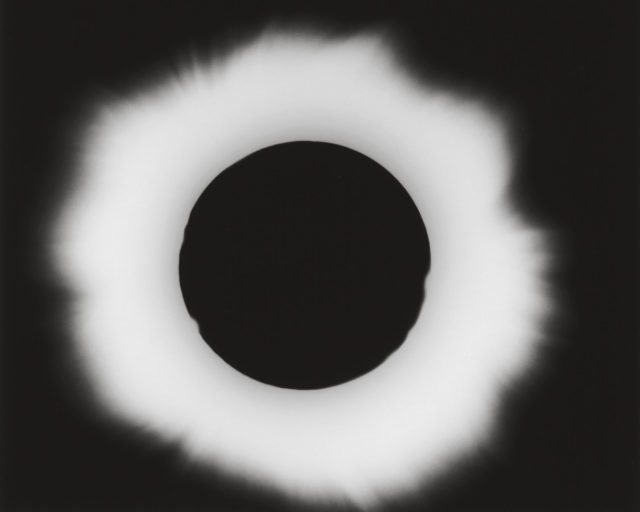

An adventurer turned photographer, Ishikawa Naoki has journeyed from the North Pole to the South Pole using only human-powered vehicles. He is the youngest person ever to have scaled the highest peaks on all seven continents, as well as K2, one of the world’s most hazardous mountains. But Ishikawa, who was born in Tokyo in 1977, doesn’t travel out of a desire to conquer nature—but rather, as he says, in order to relativize his own perspective.

For his series Archipelago (2009), made over ten years, Ishikawa traveled around the numerous island chains in the seas to the north and south of Japan. The artist’s twenty-first-century project to reposition Japan—once seen as being on the far edge of the world (“the land where the sun rises”), as one cluster in a long chain of islands in Asia—and to reconsider its history and culture in that context is an act redolent with implications. From the southernmost tip of Kyushu he traveled to Okinawa, the Yaeyama Islands, the Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, and Kinmen, a tiny group of islands situated within a hair’s breadth of the Chinese mainland that has several times become the site of fierce territorial battles between Taiwan and China. For his travels in the north, he went to Sakhalin, the Sea of Okhotsk, the Bering Sea—and even as far as Haida Gwaii in the Gulf of Alaska.

Throughout the islands, Ishikawa devoted himself to documenting local festivals and practices, as well as people’s daily lives. “There are certain realities that disappear when you package them up in language,” he says. “My idea is to break through all that, and simply present the things in the world.” His work attempts to view afresh customs and ceremonies, teasing out histories and cultures on the margins that have been overlooked in favor of cities like Tokyo and Osaka.

Festivals in the Tokara Islands, to the south, and also in further islands, are quite different from those you might find on Japan’s main island of Honshu, having more in common with traditions in Southeast Asia, the Philippines, or Taiwan. In a world we are continually being told has shrunk with the power of the Internet and the effects of globalization, fascinating customs and practices abound that are unique to particular cultural and spiritual topographies. “Before we had political boundaries, it was each local area, each locality—that was all that mattered,” Ishikawa explains. “The world was made up simply of individual places.” As we gaze at such places through Ishikawa’s eyes we experience this topographical uniqueness in a direct, unmediated way.

The photographs in this series are often compared to Shomei Tomatsu’s prizewinning 1975 book on Okinawa, Taiyo no empitsu (The pencil of the sun). But the impulse behind Tomatsu’s images is different in character—his are real-time documents shot through with experiences of the political realities of the postwar years. Ishikawa’s work, set in present-day Japan, well past the postwar period, is impelled by a more epistemological project, an attempt to express the idea of what it is to know. Facing both north and south, he fits together the various pieces of an archipelago of his own design. Today, in 2015, pivotal changes are occurring in Asia that could never have been foreseen when this collection first came out seven years ago—the China–U.S. summit meeting, the historic meeting between President Xi Jinping of China and President Ma Ying-jeou of Taiwan. The archipelago that Ishikawa envisioned now seems situated like the long arc of a bow taut with the tension of what was yet to come in the relations between Asia and the rest of the world.

Translated from the Japanese by Lucy North.

To read more from “Odyssey,” buy Issue 222, Spring 2016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.