Ishiuchi Miyako’s Chronicles of Time and History

The pioneering photographer speaks about the evolution of her career—and how she negotiated a field dominated by men.

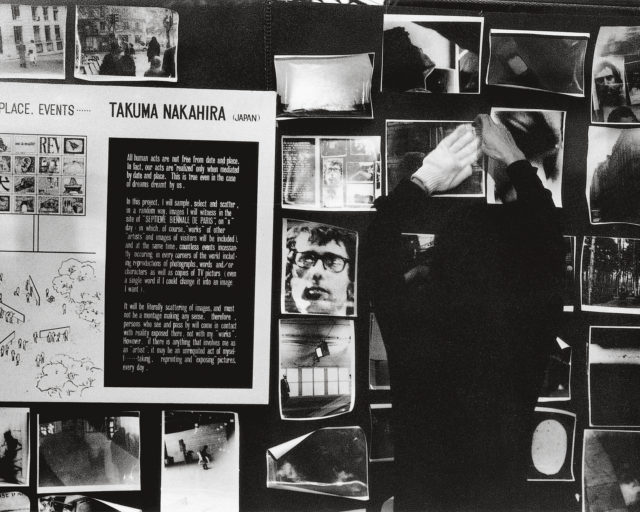

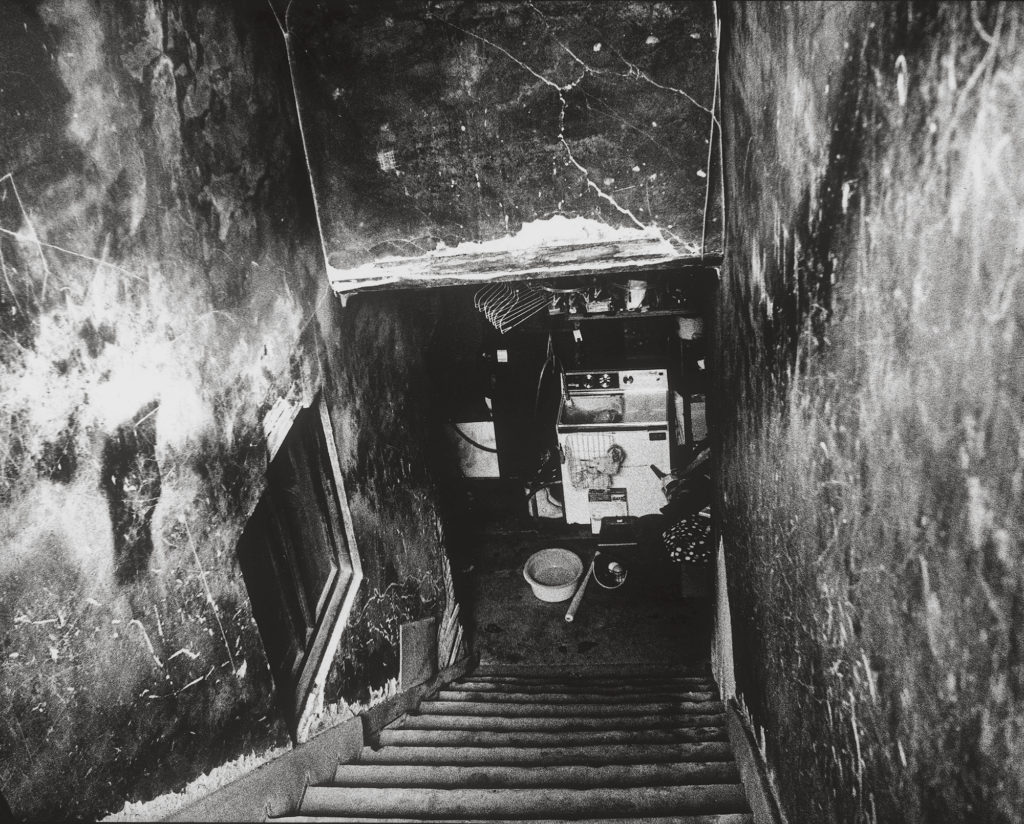

Ishiuchi Miyako, Yokosuka Story #58, 1976–77

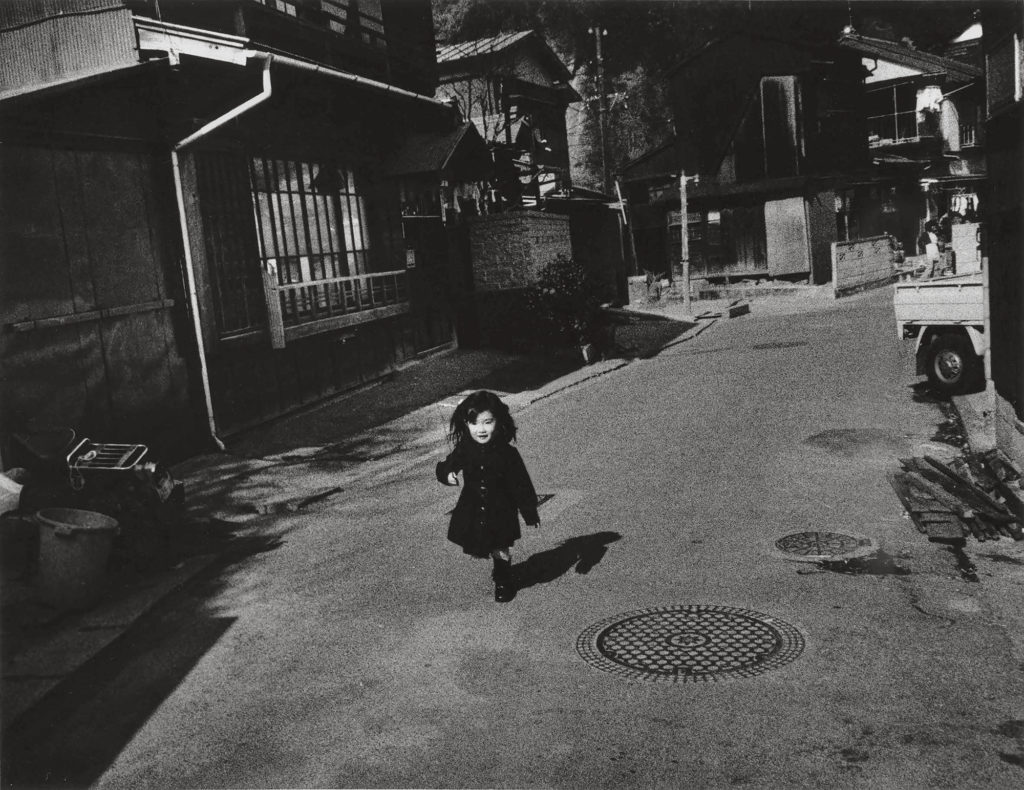

Through her images of subjects ranging from the American Occupation of Japan and the bombing of Hiroshima, to women’s scarred bodies and her mother’s and Frida Kahlo’s personal effects, Ishiuchi Miyako, born in 1947, has explored the passage of time and history. Like Shomei Tomatsu and Daido Moriyama, renowned Japanese photographers who emerged in the 1950s and ’60s, Ishiuchi’s early work was shaped by the residual presence of World War II. Her first series, Yokosuka Story (1976–77), focused on her coastal hometown, the site of a U.S. naval base that was permeated by American culture. Projects that closely followed—Apartment (1977–78), which explored the interiors of Tokyo’s postwar housing, and Endless Night (1978–80), for which she photographed brothels—honed Ishiuchi’s vision as well as her process; for her, the image is a physical object made by hand in the darkroom.

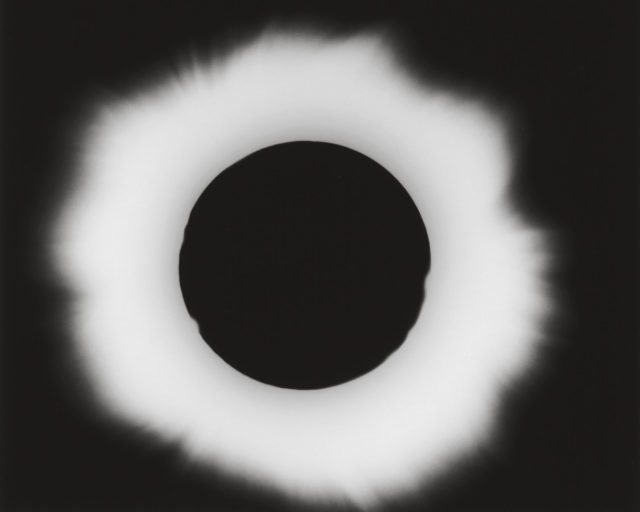

For more recent work such as Mother’s (2000–2005), featured at the 2005 Venice Biennale; ひろしま/Hiroshima (2007); and Frida (2013), Ishiuchi turned to color, taking a forensic approach to examine clothing and objects laden with complex histories, underscoring the idea that the traces of time’s passage are her true subjects. Here, she speaks with Yuri Mitsuda, curator at the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art, about the evolution of her explorations of time, her ambivalence about photography, and how she has negotiated a field dominated by men.

Yuri Mitsuda: Let’s begin with Yokosuka Story. Was this your first show?

Ishiuchi Miyako: When I started out, I was exhibited as part of a group show with Shashin Koka (Photography effect), a short-lived experimental photography group that included Hiroshi Yamazaki and Tunehisa Kimura, among others. [Nobuyoshi] Araki came, and Moriyama—well, maybe Moriyama didn’t make it, now that I think about it. But anyway, Tomatsu, [Masahisa] Fukase, all those guys came and saw it. Araki said, “If you want to show at Nikon Salon, bring some photos over.” It wasn’t really clear to whom he was talking. But when I heard that, I spoke up and said, “Sure, I’ll do it, though only once.”

Mitsuda: Why only once?

Miyako: I didn’t want to be a photographer then, but Nikon Salon was the biggest, most famous, most frequented exhibition space. And here was Araki saying, “If you want to show at Nikon Salon, bring some photos over.” I had just taken my first pictures in Yokosuka. I was absorbed in the darkroom, where I struggled with the photographic materials as objects. They were not only images to me, but materials, and somehow they stood between Yokosuka and myself. But I wanted to show them, and so I thought, Sure.

The title we’d come up with was Yokosuka Elegy. But when we showed it to [Jun] Miki [then the director of Nikon Salon], he said, “No, no, that won’t do. Much too dark.” So he renamed it Yokosuka Story. That was right when Momoe Yamaguchi had that popular song, also called “Yokosuka Story.”

Mitsuda: What did you bring to Araki’s place to show him?

Miyako: 12-by-10-inch prints. About a hundred of them.

Mitsuda: When I’ve asked you before how you started taking photos, you’ve told me, “I haven’t always wanted to be a photographer—it’s more that, from time to time, that’s the equipment I end up using.” It might have been by chance that you ended up taking photos, but nonetheless— at that point you had at least a hundred!

Miyako: That happened once I made the decision to shoot in Yokosuka. Up until then, I had no idea what I wanted to shoot. I went up to Miyako, in the Tohoku region, and I ended up in the station, unable to take a picture of anything. I didn’t know what I should shoot. I just knew people brought their cameras to different places and took pictures. That was the first time I took a camera on the road. I ended up in the waiting area, sitting there wondering why I’d come so far, why I wanted to take pictures here in this faraway place. Then it came to me—what place was I the furthest from really knowing? Yokosuka! Where I’d come from! (I moved from Gumma Prefecture to Yokosuka at the age of six.) So I packed up and went straight back.

Mitsuda: From the very beginning you treated your photographs as objects that one could craft.

Miyako: I threw my whole body into the printing process; to treat a print as something throwaway would be impossible for me. That’s why it doesn’t feel like I’m developing photos. It’s more like I’m making something.

I didn’t learn photography from anyone. I received a pamphlet for a workshop once. It was Tomatsu’s school. I went back and forth about going, but then I saw how expensive it was—200,000 yen for half a year! I decided to do things myself instead. I might try and fail, and I failed a lot. Failing is so important. It’s been such a plus for me, never having been taught photography. Though I’ve been told I hold the camera strangely.

Mitsuda: What is the allure of the darkroom for you?

Miyako: It’s the dyeing process. Dyeing white paper, bit by bit. Each tiny chemical grain, one by one, transforming the paper. I did roll printing, after all, when I was starting out. From the Yokosuka series on, I would start by buying a roll of photographic paper and then cut it as I went. But it always

struck me as crazy that the size of the paper and the size of the film didn’t match. My film was 35mm, and the paper was 4 by 5 or so. When you developed a 35mm image on it, there was so much white. So much white! It was really shocking to me. I developed in two steps. I had to add the black border myself. White seemed like simple excess, and it always stood out, and it really affected the sense of spatial composition to me.

Mitsuda: You considered the paper rather than the image, how the paper had to be incorporated into the finished work.

Miyako: I’d decided my project was not going to be documentary. When you think of Yokosuka, the first thing you think of is documentary. Tomatsu shot it, and so did Moriyama. They all ended up shooting Dobuita Street [the street notoriously frequented by sailors from the Yokosuka U.S. naval base]. That street was America, not Yokosuka. I saw everyone shooting Dobuita and calling it Yokosuka, and I thought, Something’s not right about this.

Mitsuda: It all seems connected, how you were working then: you wanted to shoot Yokosuka, not Dobuita Street; you wanted to avoid the documentary approach and shoot “your” Yokosuka; you wanted to avoid white borders and use black ones instead.

Miyako: I didn’t want to make my photographs “photo-like.” I wanted to emphasize the presence of the photographic paper itself. I thought it was really something, the sheer physicality of it. To be Tomatsu-like, for example—that meant being documentary. I represented the furthest departure from that kind of thing. What did that really mean? For me, I wanted to present the images right on the walls. I stuck them on with double-sided tape, but they started to fall down, so I bought tacks, enough for 150 photographs.

Mitsuda: Putting all the images into matted frames and lining them up along the wall wouldn’t do.

Miyako: You don’t really look at them that way. You end up moving on to the next image right away. I want to make the viewer stop and really look at each photograph. That’s why I tend to show as few pieces as possible. Like with Silken Dreams (2011). That was an experiment to see how far I could go, if I could display just one image per wall. When I had a show at the [Tokyo Metropolitan] Museum of Photography, people said, “There aren’t enough pieces!” It might have seemed quite paltry to visitors who came just to see images. But I wanted people to look at the pieces more than once— ideally, to look at them again and again.

Mitsuda: Looking at your work again, I’m struck by the themes of the body, of flesh, of flesh and photograph relating to each other. Capturing precisely the way the sensory aspect of a photo- graph, a photograph’s surface, relates to the flesh, to the skin. They have a bodily quality, these prints, even something like the building in Apartment, the feel of the tile, the feel of the dirt, it comes across so vividly. In Apartment, and in Endless Night too, the tile makes an impression. You can think of it as the building’s flesh, perhaps.

Miyako: I considered becoming a tile layer at one point. It was what I would do if I ever quit photography. I’ve always loved tile. It excites me, looking at a black-and-white checkerboard pattern, for example. When I shot Apartment, I did think of it as shooting the body of the building. I felt tender toward it, a certain pity. A building can’t move. It has to stay where it is forever. That’s so sad, I thought. A building has no choice but to sit there and accept everything that happens to it.

Mitsuda: Perhaps your pictures feel visceral because of your darkroom process?

Miyako: I don’t know about that, but I have always thought that the darkroom is such a sexual place. Its smell is so strong. And if you do it with bare hands, it’s like you’re having sex. Photography has that quality; it engages the five senses. It possesses something like sexuality.

Mitsuda: So the darkroom had a sexual quality. You can see it in the prints you made, their analog quality. And you also felt the building was a type of body.

Miyako: Yes. I thought of people as being part of the walls. I shot plenty of humans in Apartment, but as if they were part of the walls. Like patterns on the walls. People move away; they disappear. Two years pass and it’s all different. So as the humans pass through, leaving their scents, their body odors, their forgotten possessions, the building remains, silent witness to it all. A wall is a skin, you see. That sense was particularly strong in Endless Night. Those were brothels.

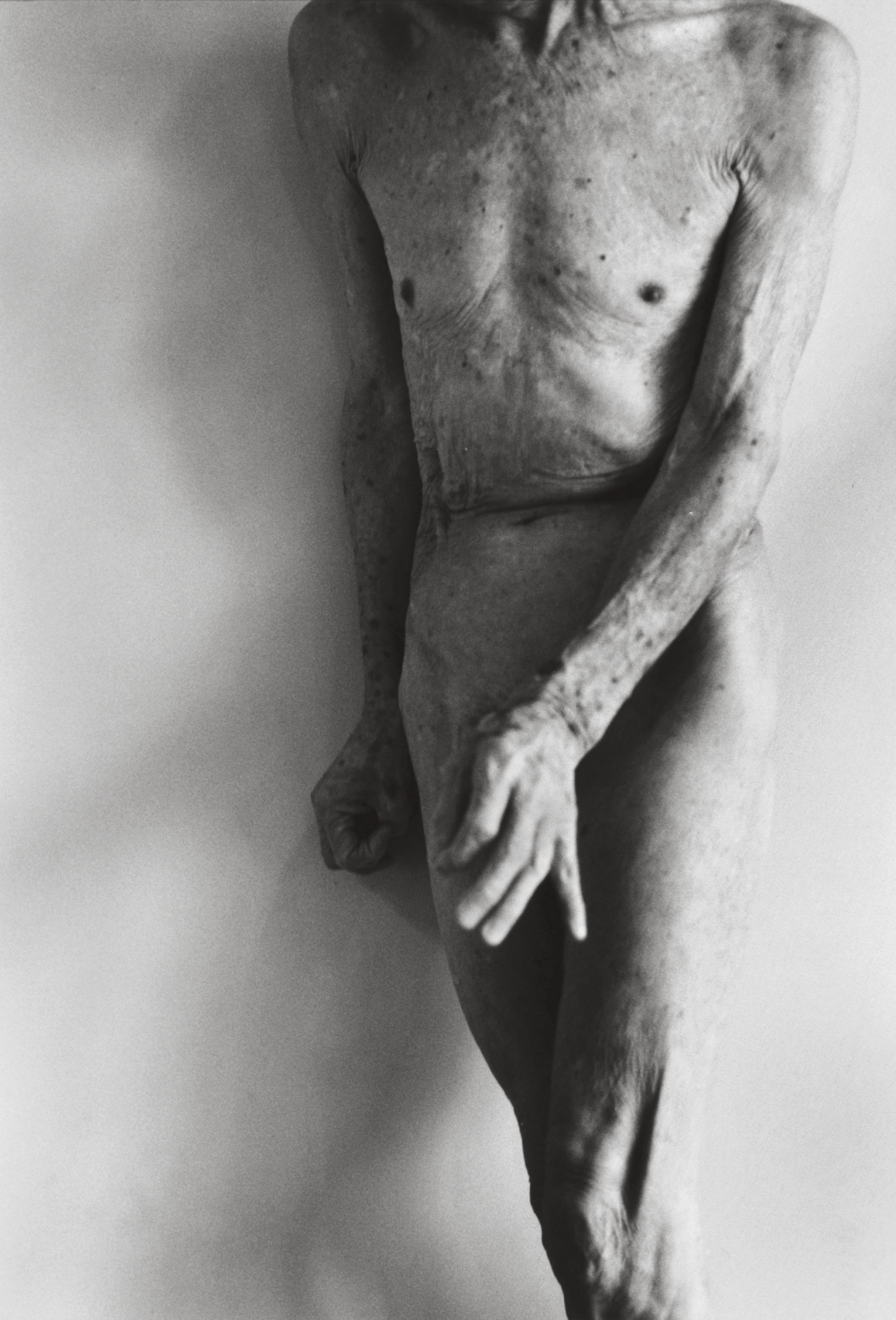

Mitsuda: The Scar (2006) work focuses on actual wounded bodies. It strikes me that the building photos resemble these. You said, “Space is formed from the accumulation of detail,” but you might also say that a body, too, is formed from details fitting together.

Miyako: You can say I’m shooting scars, but that’s not really what I was doing.

Mitsuda: Really?

Miyako: Just like in Endless Night, I wasn’t shooting tile. I was shooting time. The traces of time’s accumulation. Like I did in 1 • 9 • 4 • 7 (1990). I was trying to shoot the traces of forty years’ passage.

When I think of where in the body time builds up the most, it’s the hands and feet. Shooting photographs, you end up shooting surfaces, but I wasn’t shooting hands and feet; I wasn’t shooting scars. I was shooting something invisible to the eye, something on the far side of the images themselves.

Mitsuda: You’re using the word “time,” but, for example, with Yokosuka Story, you have the prewar, the war, the American incursion, and then you were born and eventually picked up a camera—your photography suggests layers of time. It feels less like a span of years and more like history itself. Through Mother’s, all your work strikes me as being personal. After that, there’s ひろしま / Hiroshima and Frida.

Miyako: Hiroshima was an enormous tragedy, socially and historically. I had people who could bring me into that, if you will—I had those girls who’d worn those clothes and left them behind for me. With Frida, too. They invited me, so I went. I didn’t have all that much interest in her because of my limited knowledge.

Mitsuda: That’s a fascinating aspect of your work. You never really had that much interest in Hiroshima. You also say that you never really even had that much interest in photography.

Miyako: I’m a cold fish that way. There’s always a distance from photography, since the beginning.

Mitsuda: But your photos are so intense, so hot.

Miyako: No, not at all. There’s always something about them that’s cold. Maybe because I never really wanted to become a photographer, never really loved photography itself. With ひろしま/Hiroshima it was a question of what made me able to shoot it. If I hadn’t shot Yokosuka, I wouldn’t have been able to shoot Hiroshima. They’re connected at a fundamental level.

Mitsuda: Looking over ひろしま / Hiroshima, it seems that the images you chose have a certain transparency to them.

Miyako: Well, I shot for luminescence. All of them were shot in natural light. It’s almost seventy years after the war and yet there are still new things, preserved from that time, coming to light—isn’t that amazing? I go to visit and end up getting told, “We have some new pieces.” It’s shocking.

Mitsuda: They’re still alive. These personal effects.

Miyako: Exactly. People can’t bear having them any longer. They can’t bear them alone. So they bring them to the museum, make it so we all can bear them together. This kind of history is lost, usually.

Mitsuda: Your project is so different, though, from something like what [documentary photographer] Ken Domon did, or Shomei Tomatsu. It’s similar in that it’s a way to demonstrate that people’s lives became defined by this event, but it’s such a different approach, taking pictures of people’s clothing but not people.

Miyako: When they were displayed at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, people said, “Oh, they look like high fashion!” Because the images were so pretty, you see.

Mitsuda: How do you respond to that? That doesn’t sound like praise.

Miyako: Oh, I disagree. I took it as a compliment. I mean, what’s wrong with that? I shot them to be beautiful. The response was interesting when they came out as a book—people in the fashion industry, who work with clothing, were so enthusiastic. Rather unexpected. Fashion models buying my photos!

It’s because I didn’t shoot the clothes worn by the victims as artifacts. These fashionable young women lived, and while they’re no longer with us, they left these things behind. These clothes are really nice, I thought. So that’s how I shot them. To do them that service. If you look, you can find bloodstains. You can see how they’re torn. They went through the bombing, after all. I read later about Comme des Garçons, about Rei Kawakubo and what they called the “postnuclear look.” I was so surprised. I wasn’t so far off after all, I thought. I’ve learned so many things shooting ひろしま/ Hiroshima. Thinking back over it now, it’s striking me anew. It’s quite an ordeal, this project.

Mitsuda: You mean, an ordeal to keep shooting it?

Miyako: I had no interest in Hiroshima, as you know, to the extent that I didn’t think I even needed to visit it. Now I have this bond with the place, even think of it as a second home. Yet I’m still an outsider. Though it’s because I’m an outsider that I can shoot what I shoot.

Mitsuda: That’s important, isn’t it?

Miyako: It was the same with Yokosuka—I could shoot it because I was an outsider. I’d moved there, after all. I wasn’t born there. And with Hiroshima, I was a complete outsider, so that sense of distance remains. One must be a bit cold to be the one taking photos. Up until recently, I’d never known anyone who’d been directly affected by the bombings. I was able to admit: I don’t know. It is impossible to completely understand [the event]. And in doing that, I was able to take on the burden of responsibility for Hiroshima. I’ve only come to this way of thinking recently. I was being interviewed at a museum, and the woman I was being interviewed with put it that way, that the unimaginable was the unknowable. If you can’t even imagine it, then you know nothing about it.

Mitsuda: It’s like what Wittgenstein said: “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.”

Miyako: Yes, that’s it. The unimaginable signifies that which you can’t conceive.

Mitsuda: It’s like Fukushima.

Miyako: That too. Everything to do with the earthquake in Tohoku.

Mitsuda: I had the thought, looking at Frida, that the distance between you and Frida Kahlo isn’t so great.

Miyako: I’d never had much interest in her, but when I went to Mexico City for the shoot, I came to love her work quite a bit, especially her drawings. The drawings have such lightness to them.

Mitsuda: Looking at the things Frida’s absent body once touched, the traces she left behind, her shoes—they’re not unlike scars. The distance between you and the subject in Frida seems narrower than it is with ひろしま / Hiroshima.

Miyako: I think so, too. It became about the everyday life of an individual woman, but in a way, also her life as a whole. She’s always spoken of as being so intense, so willful and passionate. But that’s just one side of her. No one knew Frida as she was in her daily life. Looking at these things, it really struck me. “Ahh, that’s how she was.”

Mitsuda: In Endless Night and other works like that, you were shooting buildings as bodies, shooting the time those bodies held within them. Were you shooting time as it existed within the spaces of the present?

Miyako: Time itself is accumulation. I’m about to turn seventy. It’s pretty shocking. How can one conceive of seventy years’ passage? There’s not much future left. Maybe twenty more years. I know I’m about to disappear. So it becomes even more imperative for me to treat time with importance. To shoot a photograph is to fix time in place. To fix time like that—I’m only interested in fixing time in its accumulation.

Mitsuda: For 1906: To the Skin (1991–93), you shot Kazuo Ohno. He’s a famous dancer who’d danced with the likes of Tatsumi Hijikata [a founder of butoh dance]. You took nude photos of him, using your signature approach—focusing on different parts, on the surface of the skin.

His body in particular seemed to show the passage of time very vividly. Normally, you think of dancers as young, vigorously moving across the stage and displaying amazing technique and then retiring before time really registers on their bodies. But he continued to dance until he died, dancing even in a wheelchair. And it was so lovely, a kind of dance only he could do.

Miyako: How can I put it? He was like an angel, and so androgynous. As if male and female didn’t matter. There was something very masculine about his flesh, though, his hands and feet. Yet they were smaller than mine!

He was quite willful. It was a difficult shoot. I had thought I was going to photograph his feet and hands, but then I started to have other ideas as I prepared to go. I wanted to take photos of the scars of men. “If you have no scars, then you will pose nude.” That’s what I told him. He was rather obstinate. I asked, “Ohno-san, do you have any scars?” and he said, “No! I have no scars.” So I said, “Could you disrobe for me then?” and all

his clothes came off, just like that! I was a little surprised. He put on some music, and then started to dance. It was overwhelming for me. Though also a pleasure, of course. It felt like rising up to heaven. Just us, no one else around.

Mitsuda: You put out Main, an independent magazine, from 1996 to 2000, with photographer Asako Narahashi. Did you want it to be like Provoke? There couldn’t have been very many people trying to do what you were doing—starting something run only by women, publishing photography not done on commission, but pieces you made because you wanted to make them.

Miyako: We were tired of the old-fashioned stuff. All that stuff the men were busy making, we wanted to get away from that. We don’t need men, I thought. They’re such a bother to deal with, let’s just do it ourselves. We wanted a venue for the things we were doing right then.

I didn’t have much connection to the photography world. I didn’t really get on with anyone, so I don’t know what they said about us. I was so impudent. I acted from the start like we were equals. And that was so much more interesting. Of course, I can’t say there was absolutely no influence from the Provoke-inspired style, it seeps in, but I can say the influence wasn’t direct.

Mitsuda: Were you ever excluded because you were a woman?

Miyako: Not at all. I mean, Tomatsu loved women. Moriyama too. So there were always women around. I had no interest in them that way, though, as men. There wasn’t one guy who was my type among all those photography guys. Thank goodness. But it can be an ordeal, being a woman. People constantly accosting you. I watched it happen all around me. There were a lot of women who wanted to do something in photography, and one after another I saw their efforts come to nothing.

Mitsuda: Why do you think that was?

Miyako: They underestimated how hard it would be.

In my case, I thought I would do Yokosuka Story and then quit. Like I was getting back at an enemy. Yokosuka was a difficult place for a woman because of the sexual violence that occurred there. Rape was a part of daily life, but nobody saw it as a crime. I did not experience rape myself, but it scarred me. I’m gonna kill you once and for all; that was the feeling. That city, Yokosuka, it had inflicted so much on me, so much trauma, so many scars. If I don’t kill you I can’t move on—that was the feeling I had.

You had to have that kind of intense feeling. I thought I’d do it once and be done, but of course, I ended up continuing. I looked around and thought, Well, now I’ll do Hyakka Ryoran (A hundred flowers bloom, 1976).

Mitsuda: Hyakka Ryoran was an all-woman show you planned for Shimizu Gallery, wasn’t it? So you had the sense that you needed to do things as just women, as women photographers.

Miyako: Of course I did. We wanted to do something just for women, but separate from the women’s lib movement. The mainstream world of Japanese photography was absolutely a boys’ club. People outside Japan noticed it too, and they were right. I had no interest in them, at all. The workshop group was a boys’ club, too, of course, but the form it took was different. They were interesting, at least, Tomatsu and all those guys. They were fun to hang around with. We went out drinking every week on the Shinjuku Golden Street. We had fun drinking together. I got my share of sexual harassment, of course. They were old-school guys, after all. It sounds idiotic saying it like that now, but that’s how it was.

Mitsuda: The excess energy produced by artists, by people engaged in making things—it doesn’t always lead to the most moral conduct.

Miyako: And there were plenty of people who left themselves vulnerable. But never me. I got a reputation as pigheaded, a dragon lady. But I stuck to my guns.

Mitsuda: If you didn’t, it would come to nothing.

Miyako: They’ll undermine you, drag you down.

Mitsuda: Do you mean how Hyakka Ryoran was thought of as unsuccessful?

Miyako: No, it was just completely ignored. There’s hardly any record that it happened at all. The only attention it got was in [the tabloid] Heibon Punch. They wrote about women taking pictures of men, of women making men strip naked. So that got picked up on television, as a kind of scandal.

Mitsuda: At the time, Diane Arbus was getting a lot of attention as a female photographer.

Miyako: But I didn’t have a lot of interest in her. She was a special case, though. Arbus wasn’t popular as a woman; she was popular as an American.

Mitsuda: These past ten years you’ve exhibited more and more outside Japan. Do you think that’s expanded your view on things? Were there things you encountered that surprised you?

Miyako: I was surprised by the Hasselblad Award. I was even more surprised to learn that they knew everything about me—they had all the data, right at their fingertips!

These days, I have many more opportunities to show outside, rather than in Japan. And I find that the respect people have for photography [in the West] is different. Photographers are artists. In Japan, a photographer is just a photographer. No one thinks of photographers as artists in Japan.

All photographs © Ishiuchi Miyako and courtesy The Third Gallery Aya, Osaka, and Michael Hoppen Gallery, London

Mitsuda: There’s a history of Japanese photographers saying things like, “I’m no artist; I’m just a photographer.” Especially photographers who specialize in street shots, in Ihei Kimura–style documentary photography. There’s a tendency to want to minimize the role of art, to rebel against the legacy of fine-art photography.

That was the basis, or history, on which much of Japanese photography was formed.

Miyako: Of course. And I don’t care about definitions of art, about what art is or isn’t. All I’m doing is what I feel I must do, regardless of any label.

Mitsuda: All the shows you’re putting on, all the books you’re writing: your sixties have been kind of a turning point, haven’t they? How do you feel now, looking back over them?

Miyako: I’ve had free time up until now. Everyone else has been so busy, but I’ve had the freedom to do things. So I pushed myself past my limits, to do more than I really am able to. Or rather, to do everything I am able to. I know what I can’t do, so I only do what I know I can. I’ve started to think lately that perhaps I really am suited to photography. That’s the potential of photography, to be freer and freer, to do things with ever more freedom.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue.” Translated from the Japanese by Brian Bergstrom.