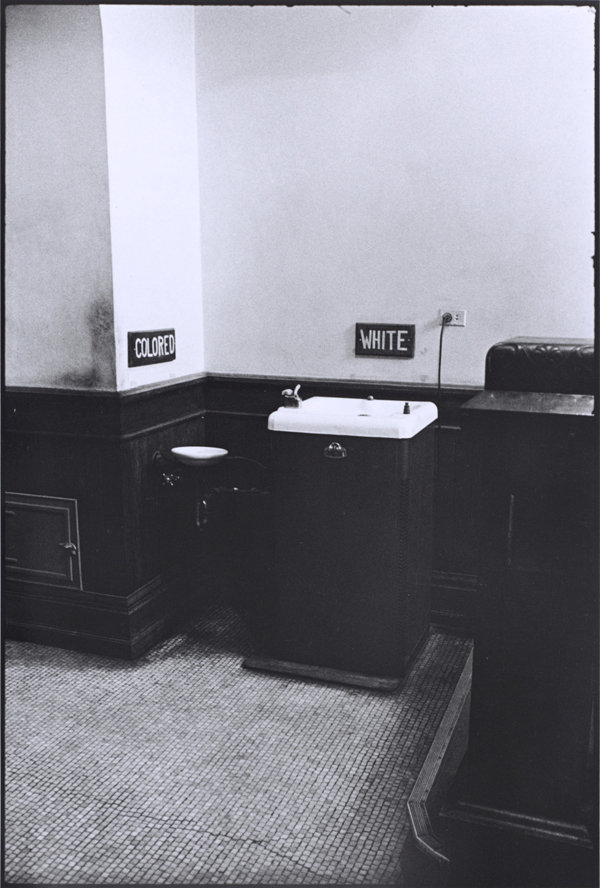

Steve Schapiro, James Baldwin, Colored Entrance Only, New Orleans, 1963

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Time Is Now: Photography and Social Change in James Baldwin’s America, co-organized by Harvard Art Museums and Harvard’s Carpenter Center for Visual Arts, is an urgent and disarmingly intimate exhibition of photographs, all black-and-white, spanning the lifetime of James Baldwin. Curated by Makeda Best in a manner that suggests the visual pace of a musical score, images from the exhibition demonstrate the photograph’s uncanny ability to immerse the viewer within the distinct psychology of past moments. Part historical reflection and part call to action, Time Is Now acknowledges Baldwin’s enormous cultural legacy by including diverse components such as an essay and books by Baldwin, a sculptural installation on Harvard’s campus by Teresita Fernández, and a series of companion events for the larger community. Last fall, I spoke with Best about the project.

Courtesy Harvard Art Museums

Ben Sloat: T. S. Eliot once said that “the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence.” I thought of this idea in relation to your exhibition, in which there’s an unsentimental recognition of the past, but also a demonstration of how these historical works bridge to our contemporary life, maybe providing a kind of guidance.

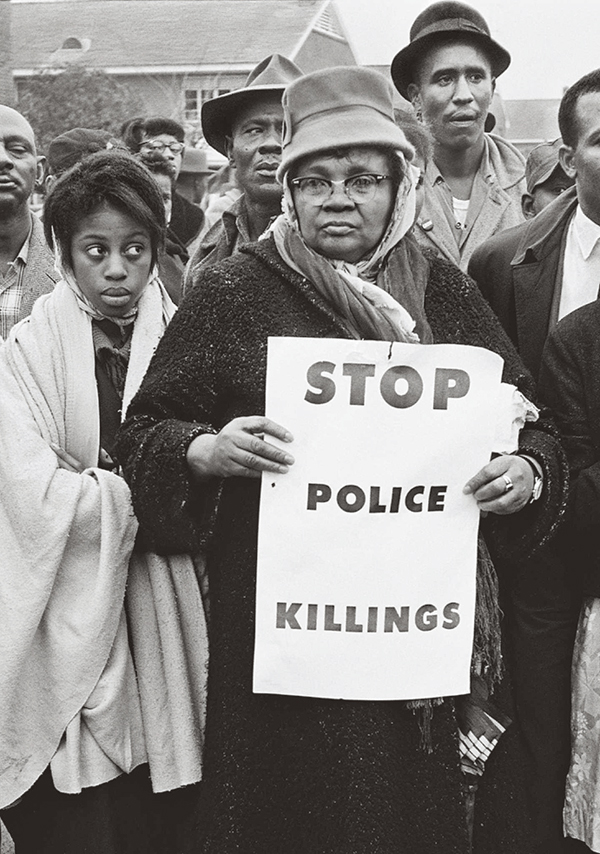

Makeda Best: That quote’s interesting, because it relates to Baldwin. The title Time Is Now is a quote by Baldwin. Someone once asked him, “When is the time?” And he said, “The time is always now.” It’s a similar sentiment; there is no past, time is always present, there’s always a present for action. Baldwin was very enmeshed in the impact of everyday life, and how incidents in everyday life transform you forever. The Danny Lyon and Marion Post Wolcott photographs in the exhibition both engage a theme in Baldwin’s work—how humiliation or other forms of psychological terror are used as a tool of oppression.

Sloat: Just as in the sole image of Baldwin in this show—Steve Shapiro’s 1963 image—Baldwin is dressed as a celebrity during the height of his fame in the 1960s, but he is still denied entry to a restaurant in the South.

Best: Yes, while being followed around by a Life magazine photographer.

Courtesy the artist

Sloat: One thing that strikes me about this show is the tether to forms outside of the photograph: there’s a nod to literature, to the magazine, to Nothing Personal (1964), Baldwin’s book collaboration with Avedon, to music, to a companion sculptural installation by Teresita Fernández. Can you talk about the expanded purview of the show?

Best: That was directly inspired by Baldwin. I was looking at someone who, as an activist, modeled so many different types of interactions. I think that’s useful for us to think about today when we think about how to be an activist. There isn’t just one form. It doesn’t mean that you don’t stick to your discipline. Baldwin wasn’t necessarily doing all those different things, but he did think very deeply about how that impacted his own work. He was an active participant in observing all of those other forms. I wanted to show that as a model for the young people who visit this exhibition. That you can participate in different communities, and how important that is to sustain.

Courtesy the artist

Sloat: Can you talk about your approach to putting this exhibition together?

Best: I had this limitation I put on myself of Baldwin’s life dates, so I really had to compress my thinking. His lifespan is important for us to consider because there are so many moments in those decades that directly influenced not only his life, but all of what happened in history. I tried to visualize what were the kinds of incidents that mattered in those decades. I began looking at what those moments were that foreshadow the traumas and the uprisings that would come later.

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Sloat: You have both an MFA in photography as well as a PhD in art history. How does that studio art background inform your curatorial decision-making in this show?

Best: I’m interested in images that create movement, on a page, or on a wall. I wanted there to be moments where you had to physically move your gaze and other moments where you had to stop. These moments of stopping, of movement, of direction, that definitely comes from my practice of photography and thinking of how images communicate.

I think I’m taking a risk here, since I’m relying on the viewer a lot to sit with this. There isn’t a lot of wall text, so I’m hoping there’s an intuitive way that people might approach this, which also comes from a studio practice. It’s an intimate exhibition; I wanted you to be close to people, and sometimes far away. That kind of dialogue I think also comes from a studio practice.

Courtesy the Cleveland Museum of Art

Sloat: What has emerged as unexpected for you from the experience of this show?

Best: The Danny Lyon image [Segregated drinking fountains, 1962] has become more and more important to me—the fact that you had to stoop, no matter how tall you were, the various levels of dehumanization to get to that water fountain. It was small, it was unrefrigerated—that you had to turn the knob. Versus this big thing that was elegant, that was refrigerated, that you would just push this button and a nice big arc of water would come out. People look at the signs that say “White” and “Colored,” but it’s not even about the signs. Look at these facilities which were just poor. And then you look at what’s next to you.

Courtesy the artist

Sloat: I find myself often caught in a one-to-one gaze with the portraits in this show. It’s a kind of a reacquaintance with the presence of the moment of the photograph being made, even with images that are historically iconic, like those of Robert Frank, Roy DeCarava, and Diane Arbus.

Best: This was a decision that was really inspired by Baldwin’s writing. He constantly writes about looking in someone’s eyes. I wanted you to focus in on a few images where you would be confronted with someone, that it would inspire that kind of looking. One of the reasons that this show resonates so much now, is that’s what we’re seeing today. We’re learning how much our everyday lives matter. How much that can totally transform who we are, the path that we take. These simple incidents that are important.

Sloat: I wanted to conclude with this quote by Baldwin: “To be locked in the past means, in effect, that one has no past, since one can never assess it, or use it: and if one cannot use the past, one cannot function in the present, and so one can never be free.”

Best: Yes, it’s a compelling idea of freedom, through our past.

Time Is Now: Photography and Social Change in James Baldwin’s America was on view at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, from September 13 to December 30, 2018.