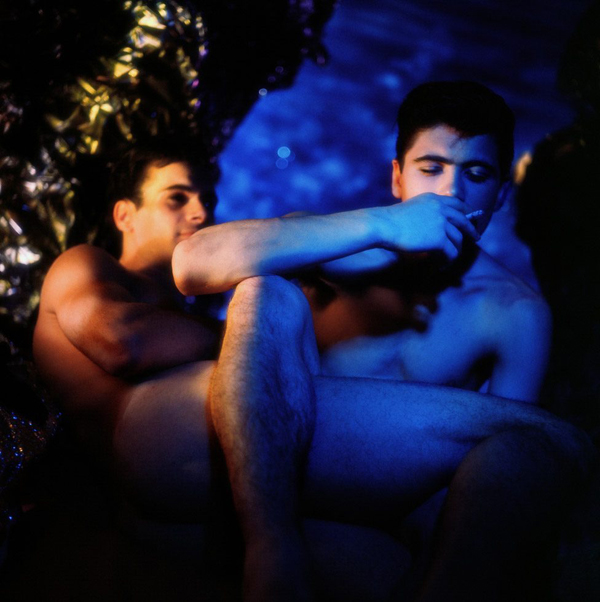

James Bidgood, Valentine, ca. 1960s

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

Reveries, the Museum of Sex’s retrospective of James Bidgood’s photographs, film, and ephemera, tells the story of an American narcissus, a boy entranced by the beauty of his own vision. Largely self-taught, Bidgood transformed tricks both male and mechanical into proofs of better, queerer worlds. Forced perspective mixed with male-on-male affection, with smears of glitter and Vaseline that blurred the male gaze into a horny swoon. It won him immortality, but became all that he could do.

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

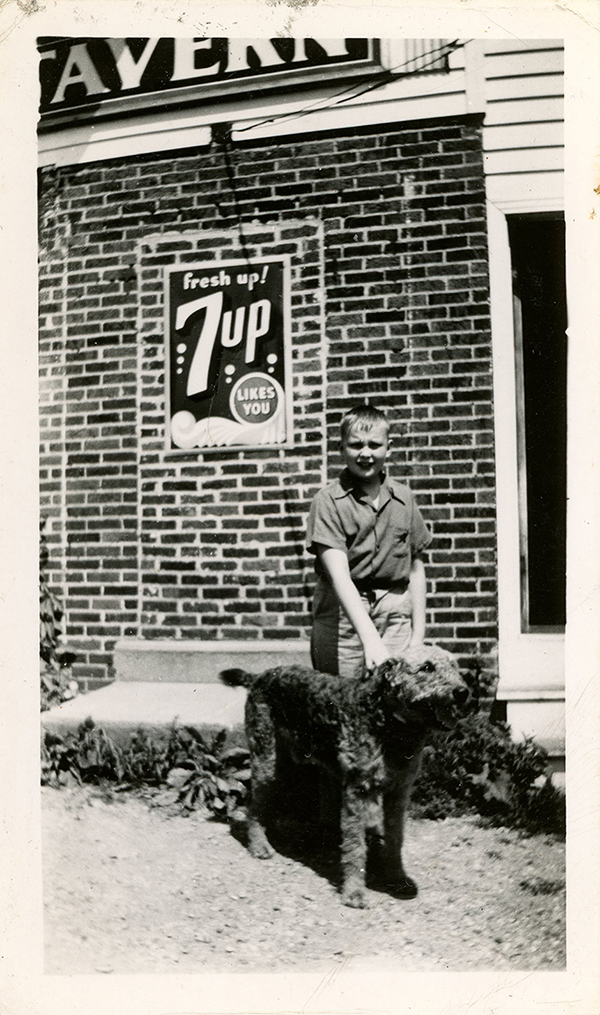

Bidgood seems to have been born (in 1933) the way certain boys are: an early personal photo in the show offers him smiling near a dog and looking somewhere over the rainbow. In Madison, Wisconsin, during the depths of the depression, he harangued his mom to buy him an expensive paper doll collection; he spent afternoons watching the Technicolor Follies fantasias. Then, at the age of eighteen, he moved to New York, ready for stardom, and while he was homeless for a while, he always says that his tight pair of Levi’s kept him out of the rain.

Courtesy James Bidgood

In the 1950s, Bidgood made himself at home at Club 82, a drag club in the Village that an article in the March 1968 issue of Man to Man magazine recalled as a favorite of Judy Garland, Liz Taylor and Eddie Fisher, and the Gabors. “Male couples are usually in evidence,” notifies author Raoul MacFarlane, “but they are vastly outnumbered by heterosexual pairs, and to the surprise of management and everyone else, the 82 has become a favorite with suburban women’s club groups.”

Courtesy James Bidgood

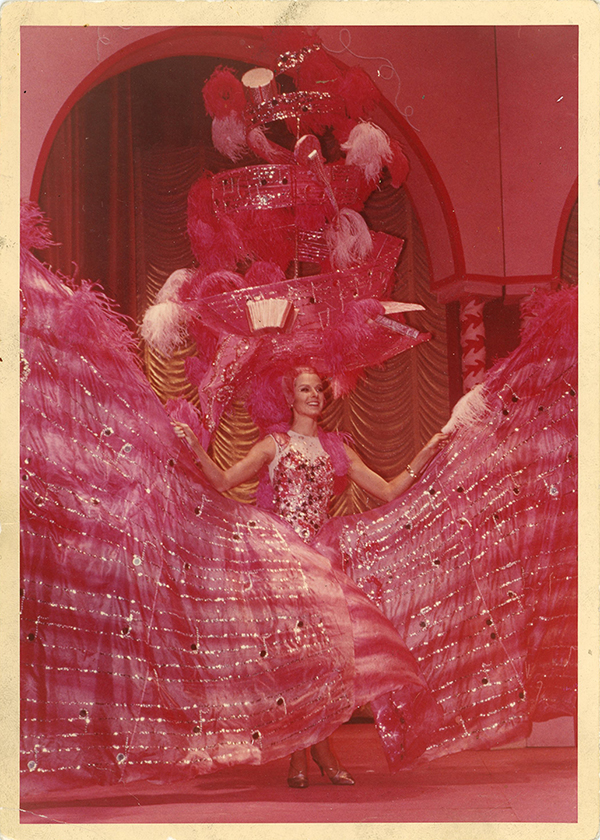

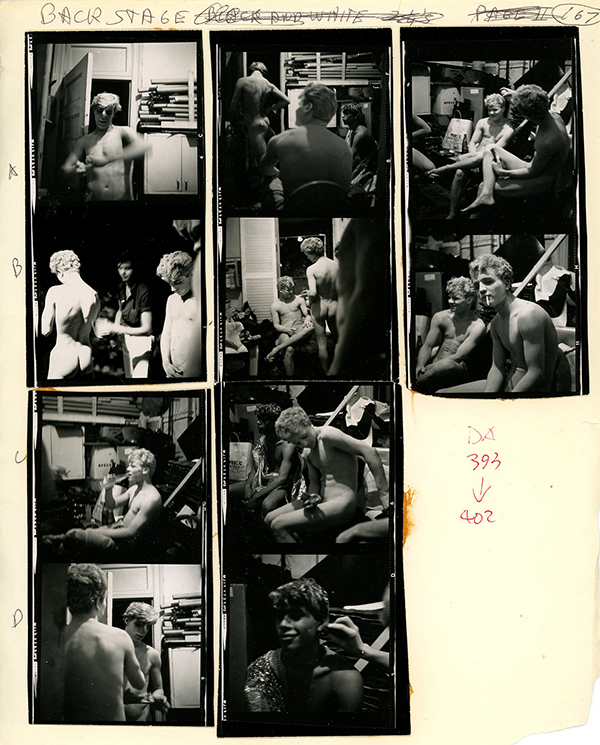

Perhaps they were window shopping. Bidgood frothed his Follies memories into elaborate set and lighting designs for the stars of Club 82, and his costumes for them and his own drag alter ego, Terry Howe. A delightful image of Howe has survived, boothed among vast heterosexuals in a clenched pose. The appeal is irresistible. By the early 1960s, the women took his gowns uptown, gentrifying them into jaw-dropping creations paraded around the Junior League Mardi Gras Ball, prefiguring similar appropriations by the recent Met Gala.

Courtesy James Bidgood

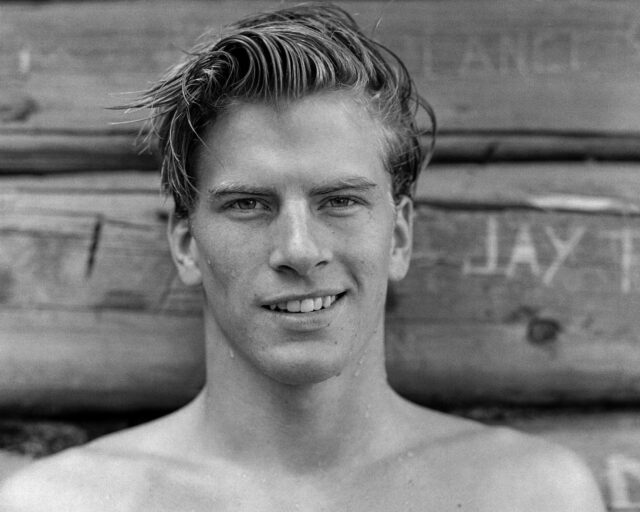

They probably didn’t ask, and Bidgood probably didn’t tell, but after the party was over the couture would trickle downtown—well, West really, to his flat in Hell’s Kitchen—where he’d refashion his vision with wit and thrift into glamourous backdrops for gay porn. Left cold by the aw shucks naturalism of Bob Mizer’s Physique Pictorial shots of twinks in posing straps, Bidgood desired his hustlers as noir heroes, photographing Jay Garvin from below in a clam-shell G-string with bejeweled nipples and a lobster in each hand that looks made of lamé. Bruce Kirkman beckons from behind chiffon boughs of willow; it made the cover of Muscleboy, a magazine subtitled Incorporating Demi-Gods that not only was the closet thing to porno the government allowed, but also offered sets of slides or art prints for a small fee, thereby seeding queer imaginations wherever the post office delivered.

Courtesy James Bidgood

Like Jack Smith’s film Flaming Creatures (1963), Bidgood’s magnum opus Pink Narcissus is less a slice of life than a smorgasbord of candy-colored novelties; like Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954), no definitive version exists. It’s a feast, starring Bidgood’s likely lover Bobby Kendall as a hero among homemade urinals that baptize the faces of bikers who themselves almost drown in pools of pseudo-semen and also threaten toreadors while Charles Ludlam hawks and licks “pissicles” from a cart. The film does have an odd puritanical streak, in which pleasures of the flesh inevitable lead to ruin—but what pleasures!

Courtesy of ClampArt, New York

Sadly, by the time the government allowed hardcore porn, Bidgood was still hypnotized by his vision, and hadn’t or couldn’t yet finish. “The big boom of porn culture,” says curator Lissa Rivera, “wasn’t his style. It wasn’t elaborate. It wasn’t something that was going to take seven years to shoot and have jewels.” It was, as they say, just too much. Producers wrenched the film from him and made a lousy 1971 print Bidgood took his name off. Meanwhile, audiences lapped up Warhol’s faux verité and the hedonism of Wakefield Poole. Bidgood went back to window dressing, and has shown little work since.

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

The bud of Pink Narcissus would bloom in the work of Pierre et Gilles and David LaChapelle and Ryan Trecartin and Greer; its gauzy shimmer shines in films like Blade Runner and Soft Cell’s Non-Stop Exotic Video Show and Prince’s Sign o’ the Times. The pink-and-blue palette prefigures the “bisexual lighting” lately gracing Janelle Monáe. While drag queens have for decades mined his work for their art, it must also be noted the exclusive focus on male bodies in racialized fantasias would likely get the film “cancelled” today.

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

But the ripples of Bidgood’s influence appear in most every artsy earnest queer on Instagram who gazed into Bidgood’s pool and saw themselves. And what remains is a wide-eyed, world-building tribute to the beauty of narcissism. “He wasn’t being ironic,” says Rivera. “He was interested in the fantasies he had since he was a boy. He’s elevating men who don’t get elevated: queer men, hustlers, people from the drag world. He loved them in this emotional visual sense. He still loves that way.”

James Bidgood: Reveries is on view at the Museum of Sex, New York, through September 8, 2019.