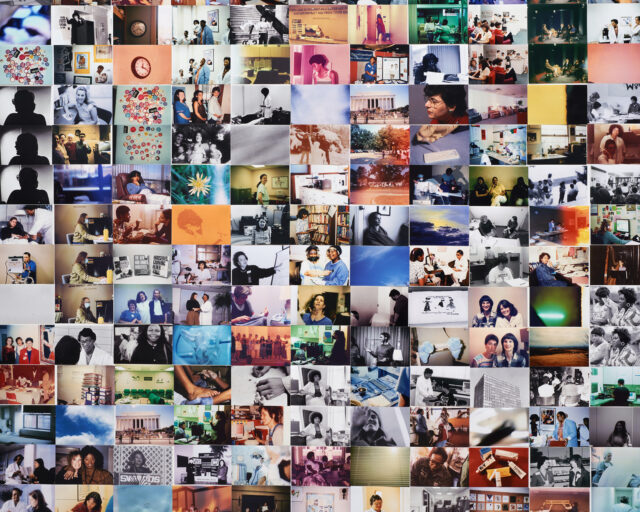

Work, Politics, Survival

© Terry Dennett and courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

Though we know Jo Spence as an activist, feminist, and socialist photographer, she actually began her career in photography operating a High Street studio business in London between 1967 and 1974. She was perturbed watching parents socialize their young into “ideal children” in front of her lens, and so helped set up London’s Children’s Rights Workshop in 1973. In Spence’s 1986 book Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography she writes about volunteering there, and how she began to explore the role of photographs in establishing certain views of childhood and normative constructions of the nuclear family unit. It’s also where she met Terry Dennett, her long-time collaborator and romantic partner, with whom she began a lifetime engagement with photography and media literacy, studying how photographs operate in the construction of age, class, and gender-based identity.

© Terry Dennett and courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

Spence’s political practice unfolded against the backdrop of 1970s London—that myriad of British counter-cultures and concomitant institutions shaped by a general desire to provide an alternative to dominant establishments and their modes of production. In 1974, Spence and Dennett co-founded Photography Workshop Ltd. in their apartment, a place where interested individuals could learn practical darkroom skills, participate in exhibitions, and engage in discussions around photography and photographic education. They also embarked on what would be Spence’s first attempt to work in the classic documentary mode, photographing inhabitants of illegal gypsy encampments throughout London. Spence refers to the project Gypsies and Travellers (1973-5) in Putting Myself in the Picture, stating:

. . . it was the classic introduction to documentary photography for me. I was both privileged and upset to be allowed to look at a world where people worked so hard to survive, whilst labouring under such terrible disadvantages. . . . It never occurred to me to teach people to take photographs of their own lives. . . . In retrospect I can see that although I was a nice liberal humanist, I had no clue as to the history of the gypsy and travelling people, or their real social, economic or political needs.

For Spence, the central question became: How can individuals—namely children, women and working class people—use photography to represent themselves, and take control of their own visual narratives? Although Dennett and Spence continued visiting gypsy communities throughout London, they did so in an old ambulance-turned-darkroom, teaching photography instead of taking photographs. Combining their technical photography skills with theoretical tools aimed at achieving agency-through-self-representation, Spence and Dennett continued teaching the marginalized, operating outside mainstream educational institutions and commercial gallery systems.

© Terry Dennett and courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

When Spence was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1982, her inclination towards self-representation and education continued, but took on new forms. The Picture of Health? (1982–6) deals with the politics of cancer as she took her physical and mental health into her own hands. By documenting her experience with Western medical orthodoxy, and recording her use of traditional Chinese medicine as an alternative, she continued her critical engagement with institutions and systems that make decisions on behalf of others, and how they treat and represent them. Her collaborative phototherapy work extends these concerns by marrying her holistic health practise of psychodrama with her applied skills in portraiture. By deconstructing and acting out scenarios from her co-counselling psychotherapy sessions—childhood abandonment when her mother was a factory worker during World War II, and anxieties around marriage and the female libido, for example—she complicates the efficacy of dominant, monolithic images of women by piecing together a portrait of herself that is multi-faceted and comprised of many selves.

© Terry Dennett and courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

Spence resisted any notion of feminist or socialist photography as a style of art making during her career, and was reluctant to solely embrace a definition of herself as a capital-A artist. In fact, she preferred to use the term “educational photographer” or “cultural worker” when describing her work. Yet, confrontation with Spence’s work invites the question, Is it art? Activism? Self help? Or, is it all of the above? Responding to a question during the tour of her Review of Work (1985–6), Spence, who died in 1992, resisted any such labels: “Somebody like me wanders, without a category. In a sense, I don’t want a category. I like being a moving target, I feel I’ll survive longer.” The undeniable staying power of Spence’s work lies in her bold approach to picture making drawn from an embodied experience of everyday life, and our inability to pigeonhole it.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.