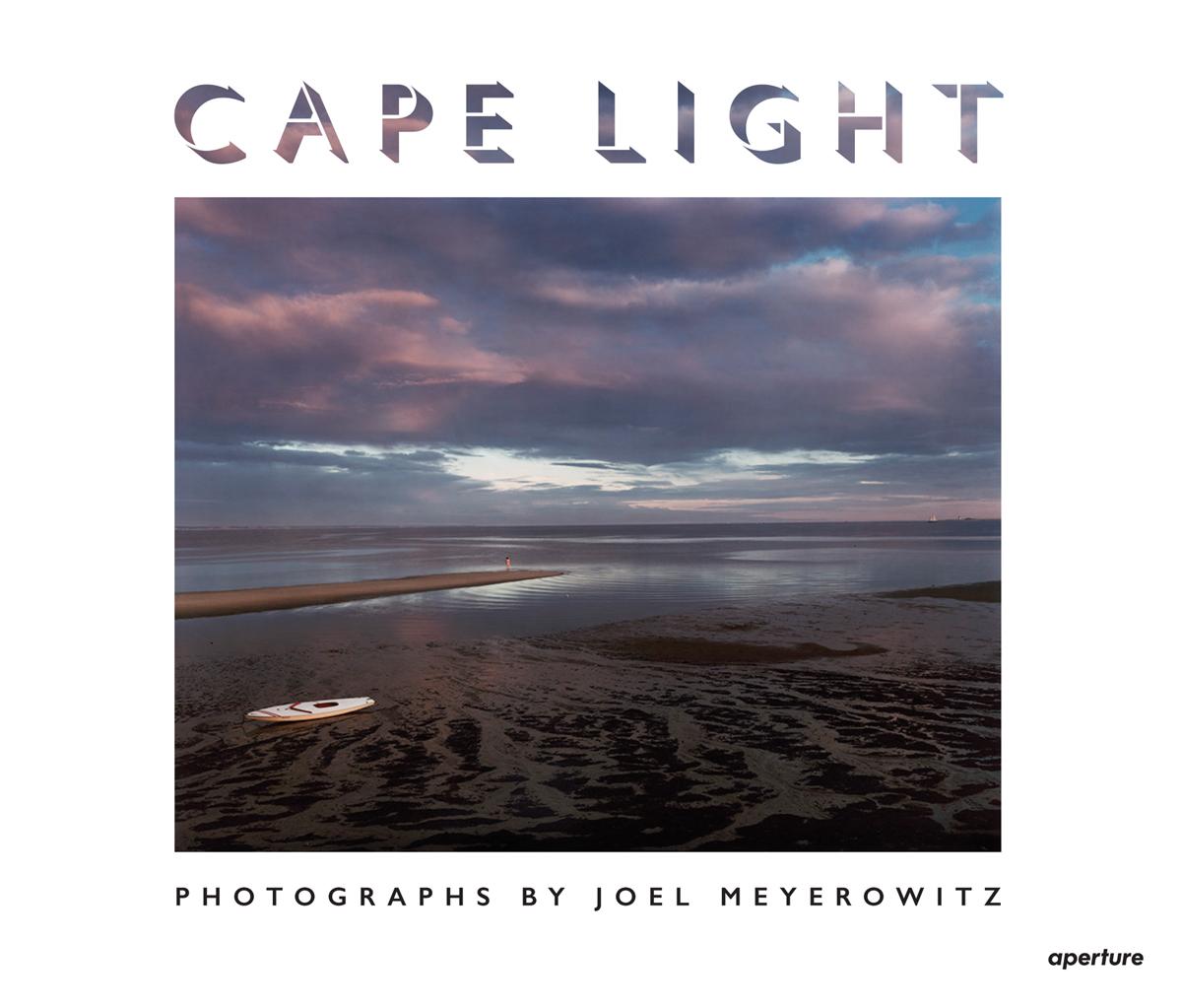

Joel Meyerowitz Reflects on the Magic of Provincetown

The artist looks back on a town that has long captivated his imagination, through every flowering of identity and sexual politics.

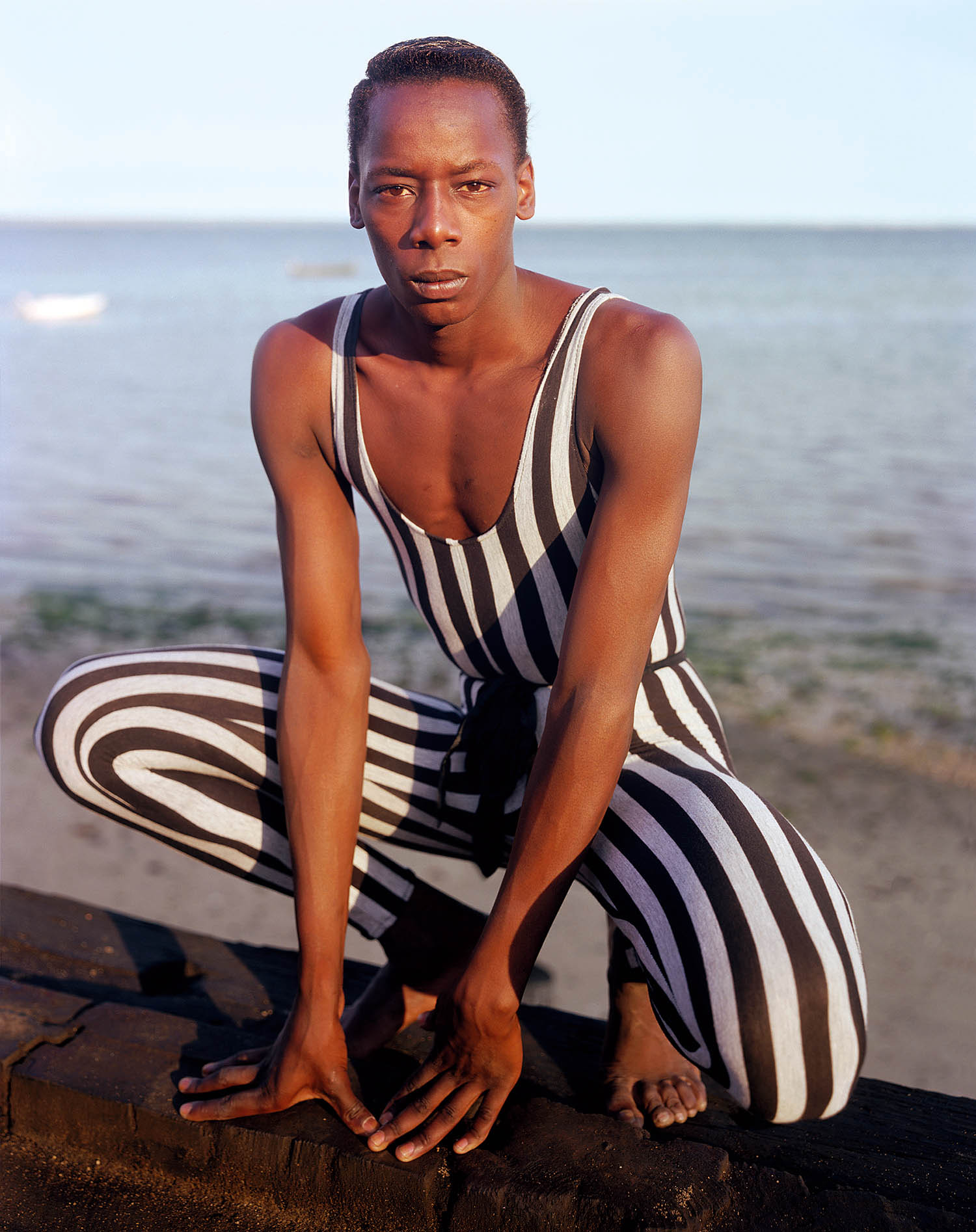

Joel Meyerowitz, Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1977

Provincetown. Land’s End. Beyond it, the wide Atlantic. People have been coming here to get away from it all since the Pilgrims came ashore in 1620. The Pilgrims stayed for five hard winter weeks at the end of the sandbar in the Atlantic known as Cape Cod before sailing across the bay to what is now Plymouth.

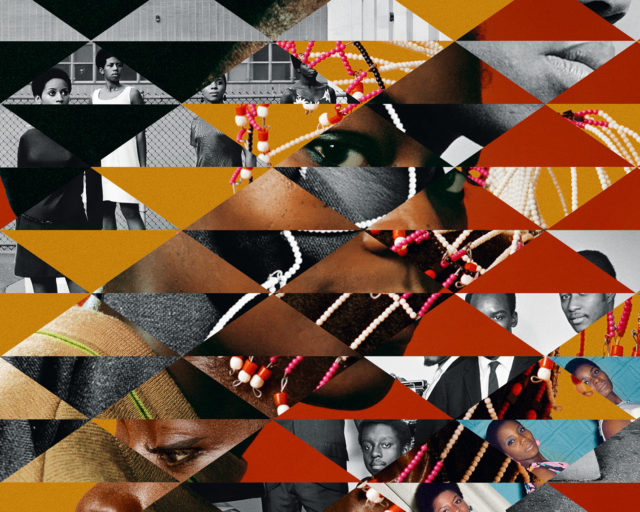

But for the rest of us who find our way here—travelers, artists, writers, playwrights, actors, poets, straight, gay, lesbian, gender-nonconforming, black, white, foreign, anyone who wants to move from the urban pressures to the spacious and spiritual beauty of the Outer Cape—Provincetown is where your identity and sense of “home” come to ground.

There is something about communities coming together at “land’s end” that creates compassionate understanding; tolerance and acceptance become the foundation of the community. P’town, as the locals call it, has been welcoming these various seekers since the nineteenth century, or even earlier. Portuguese fishermen from the Azores, picked up as crew members by Yankee whalers, settled and built a fishing community in Provincetown early on, and later, at the end of the nineteenth century, artists from New York and Boston found low-rent fishing shacks to paint in during the summers. Then, around 1910, came poets and writers and playwrights. Eugene O’Neill’s early plays were put on in the local theater. The word got out that there was a place of great natural beauty with endless sandy beaches, dunes, forests, and hidden ponds in the woods that were left over from glacial deposits of the last Ice Age, with water so pure you could drink it while swimming. A place where you could walk through the dappled light of the woods and up and over a sand dune to dive naked into the briny waters of the Atlantic.

Apart from nature, there was in P’town an animated and joyous street life, a little like Eighth Street in Greenwich Village, which brought a spicy urban flavor to this natural paradise. There were great dance clubs and bars, good music, lots of art galleries and parties, readings, and openings, all on a scale that perfectly fit the landscape that surrounded it. During my time there in the 1970s and ’80s I knew, or often saw in town, Norman Mailer, Robert Motherwell, Mary Oliver, Myron Stout, Michael Cunningham, Stanley Kunitz, Jack Pierson, John Waters, Annie Dillard, and many others. Before them there were Marsden Hartley, Hans Hofmann, Milton Avery, even Andy Warhol, and many more young artists who got the call.

What always surprised and pleased me was how kind the townspeople and shop owners were, considering the flood of day-trippers, as well as the seasonal influx of the creative crowd and summer visitors. That generosity extended to the daily circus of sexual expression that played out in the streets and hotels, the guest houses and summer rentals, in a town that, after the summer’s end, returned to the three thousand or so permanent residents who remained there through the dead of winter.”

The town lived through the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and stood strong through every flowering of identity and sexual politics of the last thirty-five years. And it did so with grace and humanity. What in many places would be judged as “other” was the norm in P’town. My kids grew up there in the summers and saw its diversity for themselves; they learned about acceptance and tolerance firsthand and have carried these lessons into their lives.

I went there originally to explore how the Cape’s light seemed to illuminate nature from within. What I discovered was the manner in which the light penetrated and exposed people’s mystery, revealing their true identities in such a way that everyone became beautiful.

All images courtesy the artist and Howard Greenberg Gallery

This text originally was published in Provincetown (Aperture, 2019) as the artist’s introduction.