Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

That everything has happened by chance might seem an odd way to begin a discussion with a photographer whose focus, intensity, precision, and sheer will are evinced in every aspect of his being, not to mention in every project he has ever undertaken. And yet this is where Josef Koudelka has chosen to begin our discussion of the work he did that one extraordinary week in Prague, August 1968, when “the big Soviet army invaded my country, everybody was against them, and everybody forgot who he was—if he was a Communist, if he was young, or old, if he was anti-Communist. Everybody was Czechoslovak. Nothing else mattered. Miracles were happening. People behaved like they never had before; everyone was respectful and kind to each other. I felt that everything that could happen in my life was happening during these seven days. It was an exceptional situation that brought out something exceptional from all of us.”

Unrelentingly alert, Koudelka is poised “to seize these chance occasions, because they can be the most revealing.” He works with an open mind and heart, knowing intuitively when, as Arthur Miller once wrote, “attention must be paid.” His acute, almost feral instincts left him with little choice but to go immediately out on the street and start photographing when Prague was invaded by Soviet-led Warsaw Pact tanks on August 21, 1968.

Koudelka is an unsentimental photographer who approaches his work without preconceptions, and with phenomenal energy and humanity, and whose own essence appears profoundly intertwined with a hunger for personal freedom (seemingly satiated). And consistent with this spirited way of being in the world is his respect for the freedom and individualism of others. Koudelka is not at all interested in talking about his photographs, or in insisting on a way of thinking about them, or advocating a particular point of view. He is, however, “interested in the picture that may tell different stories to different people,” and in what others find in his images.

Ultimately, it is all about seeing, and so the synergy between photography and painting, for instance, is a given for him—this I learned when I brought up Piero della Francesca, issues of perspective, balance, weight, and form, and how space is broken up. Consider the faces of the people in Koudelka’s photographs; look at his rendering of the gestures, the expressions of the courageous Czechoslovak people as they attempt to resist invasion, and how these photographs, taken quickly and at great risk, are so exquisitely composed. None of this is by chance.

The chance in this work is that he had returned from photographing Gypsies in Romania the day before; that a friend called him up to tell him the Soviets had indeed entered Prague, so he was one of the first to witness what was occurring; that he actually had film; that the Soviets never took his film; and that the work got out of Prague and was published one year later to commemorate the invasion. And so we begin . . .

Melissa Harris: Can you tell me a little bit about your life before 1968, before what became known as Prague Spring? Not just photographing, but what else was important to you, and whether or not you were political.

Josef Koudelka: No, I was not political. To be political in Czechoslovakia meant being in the Communist Party, which I was not. But in the period of ’68, everybody in the society became involved in politics. Czechoslovakia had been a country where nothing was possible, and suddenly, at that time, everything was possible, and everything was changing very quickly. However, what was happening in Czechoslovakia was not about revolution. It was about regaining freedom. It was the writers who first started calling for more freedom, and who, in doing so, also expressed the feelings and desires of the whole society.

Harris: Milan Kundera’s speech supporting freedom of expression at the Fourth Congress of the Czechoslovak Writers’ Union in June 1967 is so powerful:

All suppression of opinions, including the forcible suppression of wrong opinions, is hostile to truth in its consequences. For the truth can only be reached by a dialogue of free opinions enjoying equal rights. Any interference with freedom of thought and word, however discreet the mechanics and terminology of such censorship, is a scandal in this century.

Koudelka: With the abolition of censorship, everything started to change. Seven days after the Soviet invasion in Prague, we heard that one of the key conditions in the Soviets’ agreement to remove their tanks from the streets of Prague was the reestablishment of censorship.

Harris: What was important to you at that time?

Koudelka: The same as today: to do what I wanted to do. There was no political freedom in Czechoslovakia. I found my freedom through doing my work. I worked as an aeronautical engineer and at the same time I was taking photographs. I loved airplanes as much as I love the camera, but in 1967 I left my job because I realized that I could not grow much more as an engineer and I wanted to try to go as far as I could in photography. In order to be permitted to quit my job and become a photographer, I needed to officially join the Czechoslovak artists’ union, which was difficult, but I succeeded in 1965. I had already started photographing Gypsies and the theater in 1962, and continued photographing these subjects before and after the invasion of Prague. I’m always looking at many things simultaneously.

Harris: What drew you to the Gypsies?

Koudelka: I’ve always loved folk music. When I went to Prague to study I played the violin and bagpipes in a group. We used to play at traditional folk festivals. There, I met Gypsy musicians and got to know them. That’s when I began to photograph Gypsies. I think my interest in folk music helped me when taking photographs. While visiting their settlements I often made recordings of Gypsy songs. Gypsies are good psychologists: they probably understood that if I liked their songs, then I must have liked something more.

I could never have photographed the Gypsies the way I did if, in 1963, I hadn’t by chance acquired one of the first 25 mm wide-angle lenses that came to Czechoslovakia. This lens changed my vision. My eyes, my vision became wide angle. It enabled me to work in the small spaces where Gypsies lived, helped me to separate the essential from the unessential and to achieve in bad light the full depth of field that I had always wanted. By my understanding and respecting the rules of its proper use, it determined the composition.

Harris: And what about your theater work?

Koudelka: When Otomar Krejča founded the Theater Beyond the Gate in 1965, he asked me if I wanted to work with him. One of my conditions for agreeing was that when taking photographs, I could move freely among the actors on the stage. I wanted to be able to react to situations between the actors directly onstage, photographing the performance in the same way I photographed life outside the theater. I hoped to get at something real within the artificiality of the theater. By working with Krejča in this way, I learned to see the world as theater. However, to photograph the theater of the world interests me more.

Harris: Were you aware of photojournalism at the time?

Koudelka: In 1968, I knew nothing about photojournalism. I never saw Life, I never saw Paris Match. When I photographed the Soviet invasion, I did it for myself. I was not thinking about a photo-essay or publishing.

Harris: I read a great quote by Ian Berry, who I gather was the only Western photographer in Prague that week. He said: “The only other photographer I saw was an absolute maniac who had a couple of old-fashioned cameras on string round his neck and a cardboard box over his shoulders, who was actually just going up to the Russians, clambering over their tanks and photographing them openly. He had the support of the crowd, who would move in and surround him whenever the Russians tried to take his film. I felt either this guy was the bravest man around or he is the biggest lunatic around.” Apparently, Josef, this brave lunatic was you.

Koudelka: It must have been a dangerous situation but I didn’t feel it. For me, the people with real courage were those seven Russians in Moscow—the only ones out of millions—who protested that week in Red Square against the invasion, knowing they would be arrested and go to prison. I think what happened in that time was much bigger than me, much bigger than all of us. The invasion was tragic, but if it was going to happen, I’m glad I was there to witness and photograph it. During the invasion, I took photographs but didn’t develop them. There wasn’t time for that. It was only later that I processed everything. I left some photographs with the photography historian Anna Fárová. She showed them to various people, including Václav Havel. He offered to take them to America—where he had been invited by Arthur Miller—but then he was not allowed to go. Several photographs were eventually taken out of the country by Eugene Ostroff, curator of the photography department at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Fárová had shown them to him. Ostroff showed them to his friend Elliott Erwitt, who was then president of the photo agency Magnum Photos. Erwitt wanted to know whether there were photographs other than the ones he had seen, and whether I would be willing to send the negatives to Magnum. I wasn’t too keen on that—having lost my negatives previously.

Harris: What had happened earlier with your negatives?

Koudelka: I wanted to take a photograph of the Soviet tanks and soldiers alone in Wenceslas Square after the people of Prague had decided not to demonstrate so as not to give the Soviet occupiers a pretext for a massacre—the Czechs realized they were being set up. In my photograph of the hand with the watch, you don’t see the Soviets . . . I climbed to the top of one of the buildings, and the Soviets saw me. They thought I was a sniper and started to chase me. I ran through hallways into another building, and by chance found that a friend of mine was living there. I left all the film I had shot that day—about twenty rolls—with him, just in case the Soviets caught me when I left the building. The next day I returned to get the film, but he had given the rolls to someone to take to Radio Free Europe in Vienna. I wanted to kill him. So when things had quieted down, about two weeks after the invasion, and while I still had my passport (which I had only just gotten for the first time during the Prague Spring), I went with this guy to Vienna. I wanted to get my film back. Radio Free Europe had already sent five rolls to their office in Munich. We were told they were not interested in the material. I was happy to get the rest of the rolls and I brought them back to Prague, but I never got back the five other rolls.

Anyway, to go back to what happened later with Magnum, in the end, the negatives got safely out of the country and arrived in New York. Magnum supervised the printing of the photographs and their distribution all over the world.

I happened to be in London in August 1969 with a theater group that I was photographing. We went out one Sunday morning (the first anniversary of the Soviet invasion) and someone bought a copy of the Sunday Times, and there were my pictures. That was the first time I saw the pictures published. To protect my family and me the photographs were credited to an “unknown Czech photographer,” and for its internal use, Magnum stamped the backs of my pictures simply with “P.P.”—“Prague Photographer.” Then I received the Robert Capa Gold Medal for the work—anonymously—and this was announced on the Voice of America radio station. Lots of people in Prague listened to that when it was not blocked, and some of my friends began to ask me if the pictures were mine. I started to be afraid that the Czech secret police would find out that I was the author of these pictures. Magnum arranged for me to get permission to leave Prague in 1970 by inviting me to photograph Gypsies in Western Europe, and then I was given asylum in England.

Harris: This work both covers and bears witness to the Soviet invasion of Prague. Do you think of it as evidentiary?

Koudelka: Yes—which is why the Soviets and Czechoslovak government were not very happy that the pictures exist. These photographs are proof of what happened. When I go to Russia, sometimes I meet ex-soldiers who occupied Prague during that period. They say: “We came to liberate you. We came to help you.” I say:

“Listen. I think it was quite different. I saw people being killed.” They say:

“No. We never . . . no shooting. No. No.” So I can show them my Prague 1968 photographs and say: “Listen, these are my pictures. I was there.” And they have to believe me.

Harris: How did you feel when it finally became known that you are the author of the 1968 invasion photographs?

Koudelka: I didn’t really feel anything when people eventually understood I had taken those pictures. I was happy that Communists in Czechoslovakia could not say that I had only become known because of these pictures, because by the time people found out I had taken those photographs, I was already known for other work.

The first week of the resistance to the Soviet invasion was fantastic, but it didn’t last. What happened during the next twenty years was less heroic. The government became increasingly oppressive, destroying the lives of many Czechoslovak people, and trying to eradicate any memory of the Prague Spring and the resistance. I was in the Czech Republic ten years ago for Magnum’s exhibition about 1968. More than half of the young generation there didn’t know anything about the events of 1968, and most of the population that did know chose to forget. But so much has changed since then. The Prague Spring played a role in the eventual fall of Communism, so the events had significance beyond Czechoslovakia. The Czech publisher has ordered four thousand copies of my new book Invasion 68: Prague (2008).

Harris: Why did you wait forty years to do this book?

Koudelka: Nobody was interested in publishing this type of book. I wasn’t either. For me, it was much more important to produce new work.

Harris: So why now?

Koudelka: Again, it all happened by chance. I was in Prague in early 2007 talking to my publisher, who asked me about projects I was doing that winter. I answered that I wanted to finally finish the dummy of the next Gypsies book I’ve been working on for the past forty years. He said that the following year was going to be the fortieth anniversary of the Soviet invasion, and suggested that we do a book on that.

Harris: What are some of the differences in the way you structurally conceive your books—for instance, Gypsies (1975), Exiles (1988), and Invasion 68?

Koudelka: Gypsies is the result of an approach that could be called construction, in the sense that I made a conscious effort to cover the spectrum of life . . .

Harris: . . . in the sense that this body of work suggests a common experience, aspects of human life that we all share?

Koudelka: You could say that. And when I thought there was something missing, I made an effort to find and photograph it.

Exiles is the title that my editor, Robert Delpire, gave to a group of photographs we selected in the mid-1980s mainly from those I made after I left Czechoslovakia.

Harris: So the approach was in part about recognizing relationships among photographs that already exist, and in this case, the images cohere around the concept of exile?

Koudelka: Being exiled insists that you must build your life from scratch. You are given this opportunity. When I left Czechoslovakia, I was discovering the world around me. Of course, one is still drawn to certain people . . .

Harris: To me, the images comprising Exiles have a distinct choreography. The sensibility seems based in gesture and a dispersal of movement. At times there are several focal points— the feeling is not linear. So the book as a whole radiates a vitality that is different from both the intimacy of the Gypsies work, and the more reportage-like Invasion 68. What were your goals with the Invasion 68 book?

Koudelka: My aim was to present the Soviet invasion of Prague in all its complexity, and to render the atmosphere of those seven days while respecting the chronology of events. I worked with the Czech graphic designer Aleš Najbrt. Together we selected the strongest photographs and came up with the structure of the book.

We decided that the best horizontal photographs, and also the most important in terms of covering the events, would spread across two pages, and then that there would also be groupings of four photographs, which would play off each other to give more information about a particular moment or event; and then there would be sixteen photographs on a spread, which together would illustrate what was happening more broadly. Once we agreed on this concept, we started to place the images.

Harris: Did you go back through your contact sheets or the negatives previous to preparing this book?

Koudelka: Yes. Looking through all the work in my archive and at my contact sheets, I found a lot of photographs that I decided to use in this book, but I didn’t discover one picture that I would add to the ones that I have always considered the best. A good picture is the one that gets in your mind that you can’t forget. Most of my books are composed that way. The concept of this book is different. As we started placing the photographs in the structure we had determined, the book began to crystallize. Normally I work very slowly. I need to be certain that the edit, the sequence, the design . . . everything . . . has to be like that—that it could not be any other way. So I cannot believe that Invasion 68 took just one year to make.

We worked with three historians who are specialists of this period. We asked the scholars to write explanatory introductions that would be short but informative and to find documents that directly relate to the photographs.

Harris: You have a lot of primary sources in the book: official statements from the Czechoslovak government, testimonials, statements made by the press, by Soviet officials, as well as articles and other documents from the period, and information drawn from The Czech Black Book, an eyewitness, documented account of the invasion of Czechoslovakia prepared by the Institute of History, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, in the fall of 1968.

Koudelka: At the end of the book there is also a short chronology that allows the reader to follow precisely what happened, day by day. We also structured the book so that someone can immediately find the most important information: these texts are printed on black. And we always tried to preserve the essential sequence of events, although I could not always be certain of the chronology by looking at my contact sheets. Everything got mixed up when the negatives first came to Magnum in New York and they made contact sheets. Nor could I always be certain of the chronology by looking at my negatives: I photographed these pictures using a type of film that was for the cinema, which had no numbers on it.

It is for this reason that when we made the book, I wanted all available documentation to identify as closely as possible the sequence of what happened.

Harris: Invasion 68 seems unlike any book you have made before— in terms of your goals and methodology.

Koudelka: I attempt to find an approach that suits the essence of each project. I do not like to repeat myself. Repetition is not interesting after you take an idea as far as you can and get what you want to get. Otherwise repetition leads to getting stuck in your habits, which soon become rules. You get locked up in the rules and you cannot get out. So what can you do? One way is to destroy them.

Harris: To me, there seems to be a duality or tension infusing your projects. I sense always the loner, the solitary man, and yet at the same time there is often a poignant camaraderie. A feeling of tragedy permeates your work, while simultaneously it is profoundly luminous. And then, while you insist that “the most beautiful word is next,” you are one of the most present and engaged individuals I have ever encountered, which is manifest in the intensity and emotionality of the photographs. Yet you seem to just as easily leave a subject once you’re done . . .

Koudelka: What I mean by “next” is moving, continuing, never stopping. I am not leaving anything. I was born a certain way. I think I am a visual person. I look at everything. It’s not that I suddenly drop the Gypsies, or the theater . . . I may not photograph them anymore because life has changed and I am not confronted by the same situations. But one builds on what came before.

All photographs courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Harris: You have spoken a lot about personal freedom and not wanting to stay in one place for too long. Do you not want to be attached to things? Is it about not wanting to be too comfortable, so that you keep experiencing freshly?

Koudelka: First of all, you have to understand who you are.

Harris: Do you?

Koudelka: I am trying.

You asked before about attachment. I don’t want to be attached to material things. I now have two places where I can work—in Paris and in Prague. Before this, I did not have a place for fifteen years. I didn’t need, nor did I want places. I have always tried to adjust my life to the way in which I wanted to live. I am now seventy years old, and so far I’ve never had a television, a car, a mobile phone, or a computer. Sometimes I will use them. I have nothing against them. But what I don’t have I don’t need.

Harris: So what matters, Josef?

Koudelka: Everything. Everything matters. Everything. Every day is a gift. Everything matters. This morning, it mattered very much that the sun came out at 8:18 am. Tomorrow it is going to matter very much, if I am here, that the sun is going to rise at 8:16 am. Everything matters. I don’t take things for granted. Everything is present for me. And if something beautiful happens, I try to enjoy and appreciate it as much as possible.

You know, we are all different. At the same time, we are all very much the same. And each of us is trying to find the way to be in this world, and there is no one way.

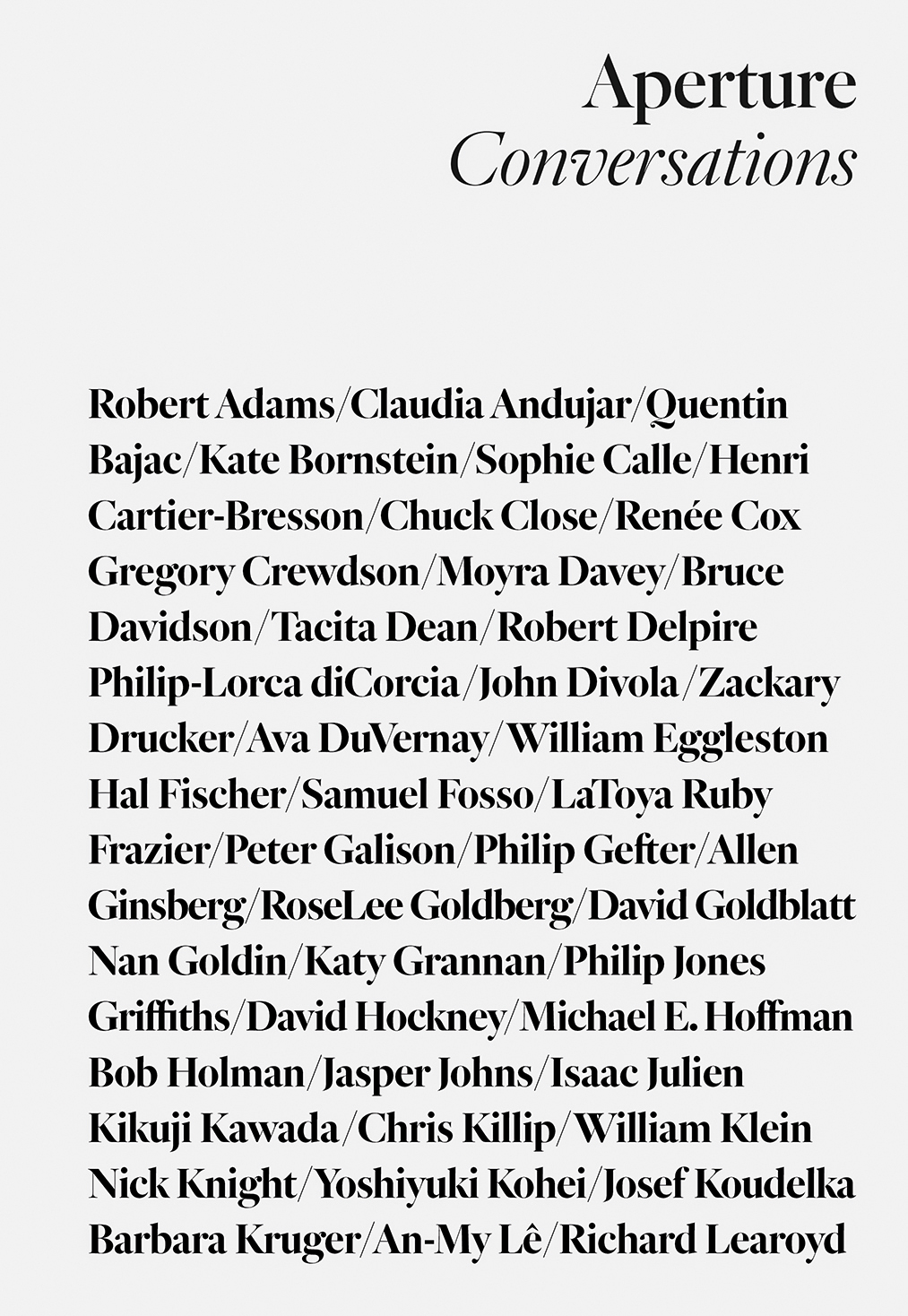

First published as “Invasion 68: Prague Photographs by Josef Koudelka,” Aperture Issue 192, Fall 2008, and republished in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018).