Judith Black’s All-American Summer Vacation

In 1986, Black photographed her family as they drove across the United States, recording the touchstones of life with intimate precision.

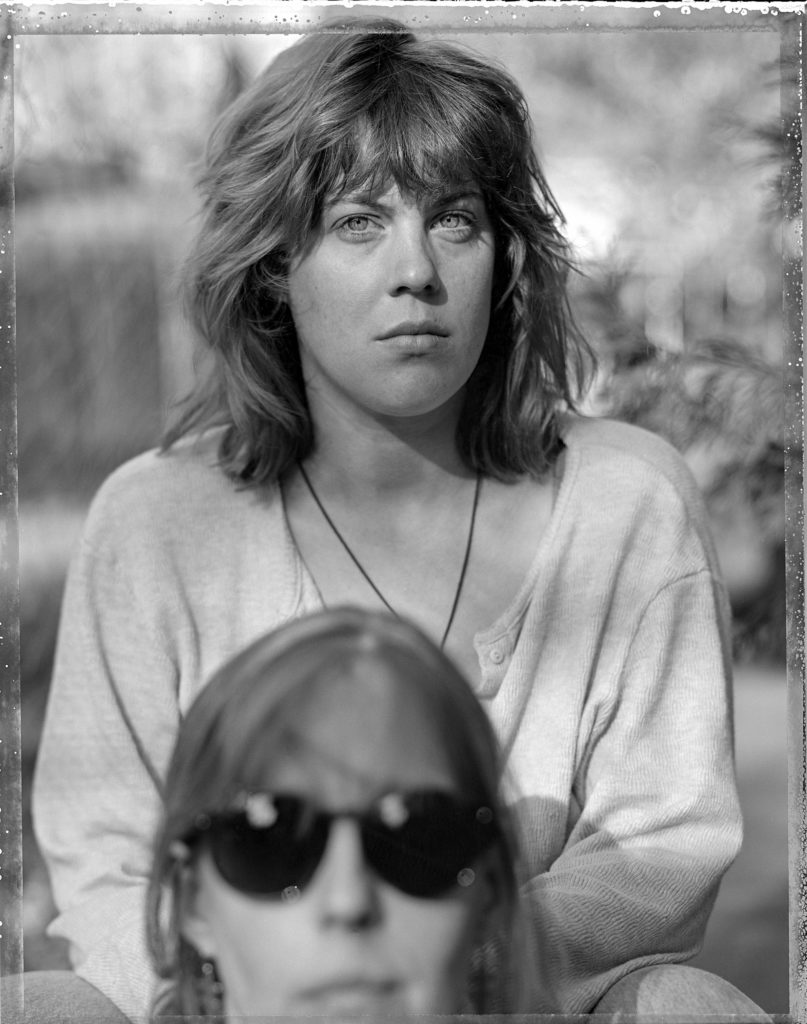

Judith Black, Cody, March 27, 1995

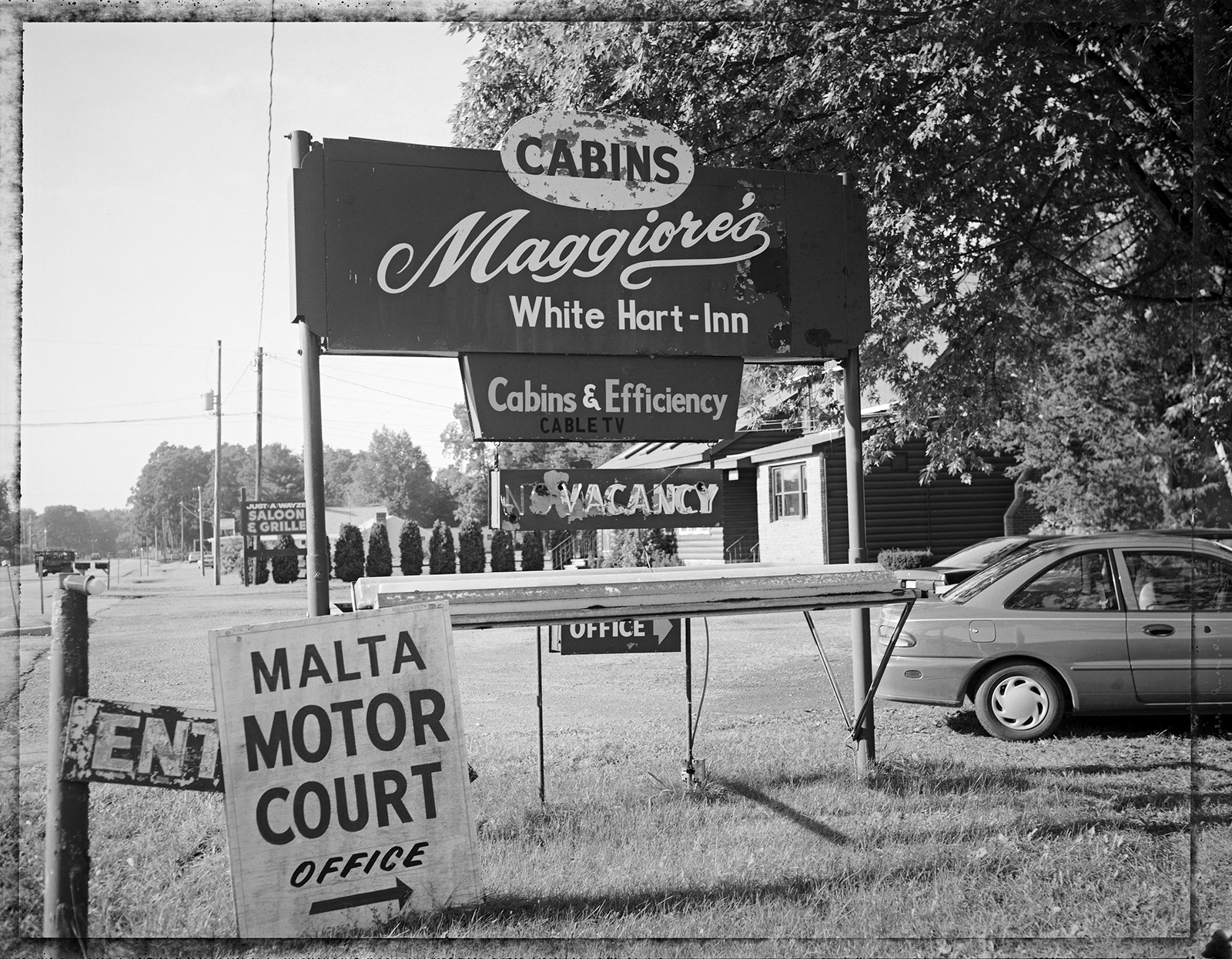

Who would have thought the title of Vacation could, in our present moment, propose so quixotic an idea? Released by Stanley/Barker on the frayed edges of a pandemic-weary spring, Judith Black’s new photobook is a tease. The photographs collected within took seed in 1986 when Black was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, allowing her to take off from her job as a photo technician at Brandeis University and document that most all-American of rites: a cross-country road trip. The starting point was her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which previously set the scene for her 2020 photobook Pleasant Street, an intimate portrayal of her family life (also published by Stanley/Barker). From there, Black departed for New York, Michigan, and Chicago, moving westward to San Francisco with a new set of cameras—and four children—in tow.

The open road is a prism through which generations of photographers have envisioned the United States. Moving freely through the American landscape and its pockets of life is a privilege afforded to few, and the canon of photography that makes transience its tenet is dominated by a male and white lens. Principal among them is Robert Frank. He set out from New York in 1955 (also with the support of a Guggenheim Fellowship) and returned two years later with a suite of images that would become The Americans, his work of monolithic influence. First published in France in 1958 and in the U.S. the following year, the book depicts a thrumming spectrum of realities, its staggered cadence determined by what Jack Kerouac called in the preface “intermediary mysteries.” Frank’s project overwhelmingly asserts the primacy of chance encounters, whereas Black offers a sort of spiritual opposite. She instead uses the trip to center her children, extended family, and friends—portraits of whom make up the heft of the book.

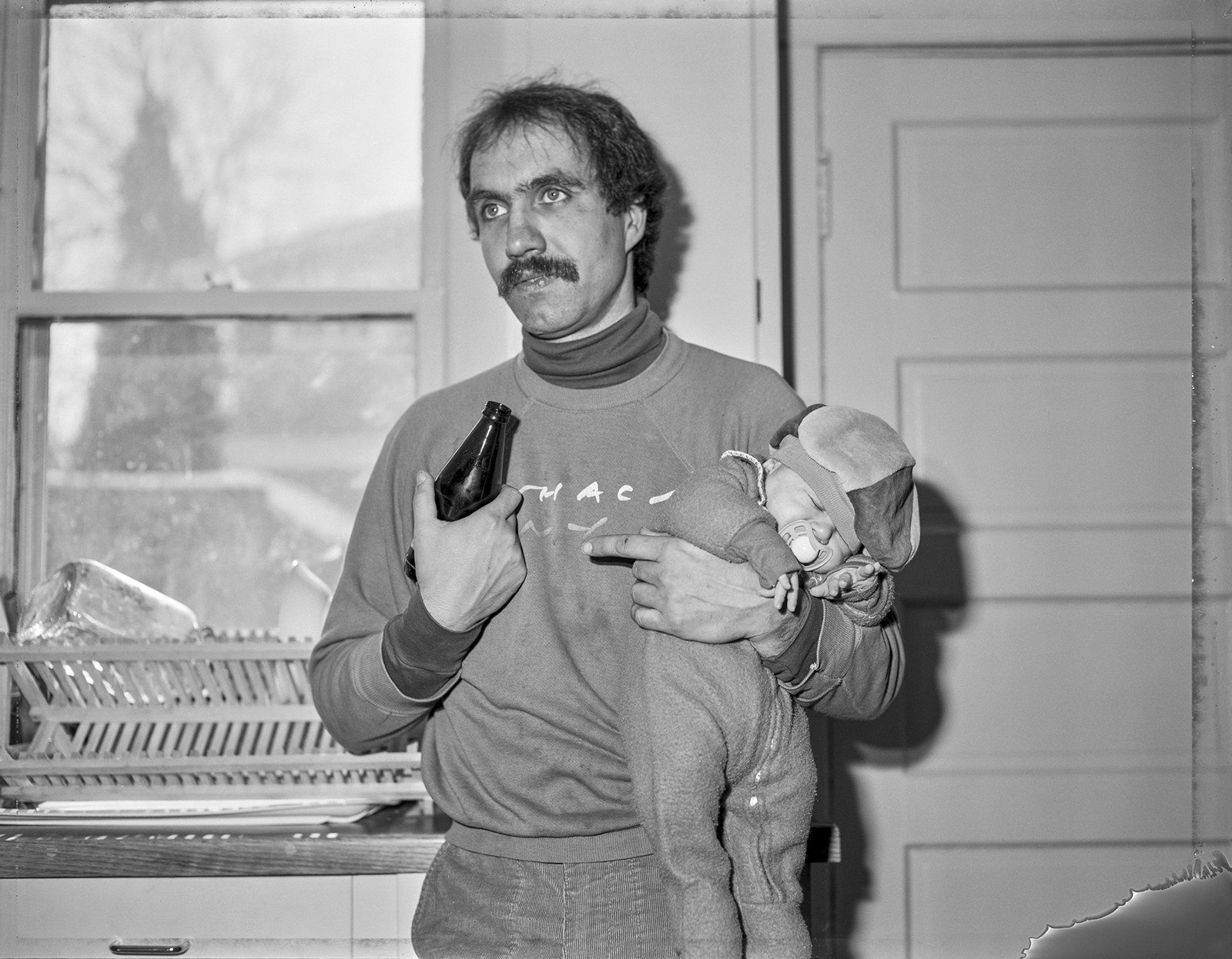

Shown on the cover of Vacation, set against an image of wild daisies and hemlock flowers, is a photograph of a sleeping infant, his somnolent consternation hinting at the mysterious activity of his mind. From there, across single- and double-image spreads, we see subtle evolutions of life. Black’s children are seen early on in the book wading into rivers and posing at tourist attractions, each one wearing the mantle of an inchoate youth in both expression and dress. As we turn the pages, this innocence gives way to a steadier physicality and self-assurance, a way of comporting themselves that reflects the passage of time. Similar shifts appear in Black’s images of family and friends, who accrue their years within familiar haunts. Black is an avid researcher of vernacular family photo albums, but her own method of photographing with medium- and large-format press cameras—often loaded with Polaroid Type 55, known for capturing exceptional detail—requires exacting technical precision, time, and collaboration with the sitter, diverging from the spontaneity of the average snapshot found in such albums. The cumulative effect of time is laid bare not just through her tenacious recording of growth spurts but also by virtue of her meditative approach. This is no shoot-from-the-hip photography but a marriage of technique and subject matter.

A photograph that strikes me, in particular, is a portrait of Black with her daughter, Johanna, taken in 1995 in Chico, California. In it, Black crouches furtively in the foreground. Her floating head is indistinct, lost in the aperture’s shallow depth of field, while Johanna looms above her, eyes lit and in high detail, addressing the camera with a well-versed directness (she appears dozens of times in her mother’s various projects). To me, the positioning of the two women signals a reverence from mother to daughter, making visible the ineffable will to uphold and make luminous one’s child.

In an essay in Aperture magazine’s summer 1987 issue, “Mothers and Daughters,” in which Black’s work was included, the feminist writer Tillie Olsen, in collaboration with her daughter Julie Olsen Edwards, describes the potential of a maternal connection to afford a “lifelong at-homeness with each other’s bodies, the sensuality, the easy tactile expression of connection.”

This idea of “at-homeness” reverberates throughout Vacation. The sights that line Black’s trip are given short shrift and seem merely to provide a mise-en-scène for her to record the tacit bonds of family. Surveying the recursive nature of these photographs, and Black’s apparent indifference to spectacle, so potentialized by a cross country trip, I am reminded of Annie Dillard’s 1982 essay “Total Eclipse,” which details her pursuit of a solar eclipse. Dillard is seduced by the promise of the extraordinary, only to demur: “One turns at last even from glory itself with a sigh of relief. From the depths of mystery, and even from the heights of splendor, we bounce back and hurry for the latitudes of home.” Attentive to this tug of the familiar, Vacation coheres an overarching verity for Black: that those close to us are often ballast amid the irrepressible magnitude of life.

With its specter of grief and lost pleasures, this past year has left many of us longing for a return to the swim of life and to revel in its vibrancy. For many, this season also restored ties that bind us and provide a tonic in the worst of times. Where absence was felt, family albums and snapshots took on a new charge, providing a thread to what used to be. These mediations of experience and people are, for Black, physical “touchstones,” containing within each of them, she writes, “sweet memories and histories.” Portraits of family, even as inadequate documents of life, assert what matters.

All photographs © the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

Black continued her project after returning to Massachusetts, where, in 1987, she became the head of the photography department at Wellesley College. Vacation ultimately spans twenty-three years, her coordinates mapping buzz cuts and births alike. For Black, the swim of life does not course along some distant shore; its ebb and flow is felt in the everyday, whether a passing embrace at a breakfast table or a child hiding between the cushions of a sofa. Vacation sets up a precept of emancipation from the domestic sphere; Black, however far she travels, is always home.

Judith Black: Vacation was published by Stanley/Barker in 2021.