Karl Blossfeldt at the Whitechapel Gallery

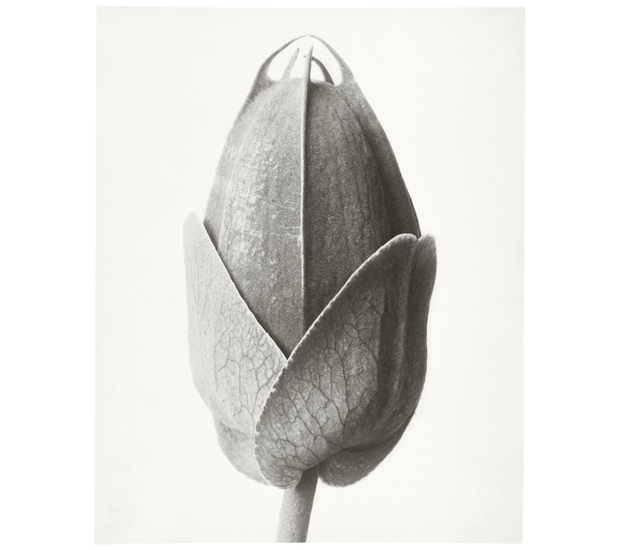

The German photographer Karl Blossfeldt spent a large portion of his life studying organic forms, selecting plant specimens like an entomologist who collects and catalogs butterflies. Yet, Blossfeldt captured his samples not with insect pins, but rather with a camera. Looking through the more than eighty original prints included in this exhibition, all produced using homemade cameras that allowed for extra magnification, one gains a clear sense of what fascinated Blossfeldt for over thirty-five years. The prints reveal grasping fronds, intricately unfolding tendrils, and stems covered in tiny rhizoids (root hairs) that seem to mutate into architectural structures, the frenetic patterned surfaces of modernist designs, or an anthropomorphic cast of curious actors.

Blossfeldt tends to be associated with the New Objectivity movement—the more realist wing of German modernism—alongside August Sander and Albert Renger-Patzsch. This grouping is not without problems, given these photographers’ profoundly different approaches to the camera, and the fact that Blossfeldt’s project, which he initiated during the 1890s, far predated German photographic modernism. The connection came about largely because the first major exhibition of Blossfeldt’s work, organized by the Berlin art dealer Karl Nierendorf, occurred in 1926, during the height of New Objectivity and Weimar photographic modernism. One of the strengths of Kirsty Ogg and Poppy Bowers’s curatorial framing is that it positions Blossfeldt’s epic project outside of New Objectivity and on its own terms, focusing on his working methods and the historical reception of his work.

The first of the exhibition’s two galleries displays five of the photographer’s rarely seen working collages. These large-scale cardboard mounts—onto which cut-out contact-sheet images are assembled in jumbled grids and sequences, with handwritten notations scribbled on their edges and crosses and lines marked for cropping—were first unearthed in Blossfeldt’s estate in 1977. Their scrapbook-like appearance suggests a less clinical or systematic approach to his work than one gleans from viewing his black-and-white gelatin-silver prints. They are testimony to the playfulness of Blossfeldt’s comparative eye, which explored the graphic and aesthetic possibilities of the plant life he documented. This first gallery helps one to look anew at the prints displayed in the second. Far from the crisp, sharp, unforgiving lines and details of Renger-Patzsch’s photographs, many of Blossfeldt’s final images are closer to works-in-progress. Once magnified twenty-five times, the fuzzy outlines of a cross-sectioned horsetail stem, or the shadowy edges of its shoot-tip, suggest that his modified camera was not always capable of the dramatic enlargements he sought.

The reception of Blossfeldt’s monumental endeavor is framed by the display of a series of his photobooks, as well as a collection of newspapers, popular and avant-garde illustrated journals, and critical essays discussing his photographs. In the first gallery, three large vitrines contain Blossfeldt’s books from the late 1920s and early ’30s, beginning with the most well-known: Urformen der Kunst, published in Berlin in 1928. (The title is translated here, as it is most frequently, as Artforms in Nature, though the German original is perhaps better understood as Prototypes of Art.) In the second gallery, another two vitrines contain Walter Benjamin’s 1928 review of Blossfeldt’s book Neues von Blumen (News About Flowers) and a copy of Uhu, a Weimar general-interest magazine that often featured the photographs of such figures as László Moholy-Nagy, Martin Munkácsi, and Otto Umbehr, known as Umbo. There is also a copy of Georges Bataille’s 1929 essay on Blossfeldt, “The Language of Flowers,” which was published in the first issue of his radical surrealist journal Documents.

This emphasis on the historical reception of Blossfeldt’s photography is an important curatorial move, as it resituates Blossfeldt’s images in the publications where most people originally encountered them. It demonstrates how Blossfeldt’s strange organic corpus was received not only in the very different avant-garde worlds of Berlin and Paris, but also in the popular press. Crucially, it undermines a tendency to canonize Blossfeldt exclusively as a modernist art photographer.

However, the Whitechapel’s presentation of Blossfeldt is not without its limitations, and ironically the commendable emphasis on production and contemporaneous reception serves to reveal these blind spots. Blossfeldt is claimed as the sole originator of the epic botanical documentary project, which in turn is presented as “one of the major influences in early-twentieth-century modernist art.” Yet the original intention of this ambitious photographic archive was not to produce modernist masterpieces, but rather pedagogical sources for German designers. Blossfeldt’s photographic studies were to serve as the basis of a manual or textbook not for fine or avant-garde artists, but for industrial, commercial, and technical designers and the mass-produced commodities they created. Further, the idea wasn’t Blossfeldt’s; it came from his professor and mentor, Moritz Meurer, who in 1889 was charged by the Prussian Board of Trade with bringing the design of Germany’s otherwise excellent technical and industrial products up to the level of international competitors at world fairs. Following in the footsteps of the architect Gottfried Semper, who in the mid-nineteenth century argued that the arts, like nature, were based on certain archetypal forms, Meurer turned to the natural world to provide a source for design. From this perspective—curiously sidelined at the Whitechapel—Blossfeldt’s nettle leaves and cow parsley stems cannot but transform before one’s eyes into the decorative wrought-iron forms of functional design and engineering—just as they surely must have done for Blossfeldt. Indeed, he must have brought this experience with industrial production and design to his photography. Prior to beginning this project, he had completed a casting apprenticeship at the Mägdesprung ironworks, a factory that produced, among other things, wrought-iron grilles and gates sumptuously decorated with plant motifs. Further, while photographically documenting the natural world, Blossfeldt produced a body of work even less well-known than his collages: a series of sculptural, educational, plant-like objects cast in bronze. Had these been included in this exhibition, they would have made clear just how much his curious and charismatic archive operated between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, between the industrial and the avant-garde, and between the sculpted or mass-produced object and the photograph.

Sarah James’ book Common Ground: German Photographic Cultures Across the Iron Curtain was published this month by Yale University Press.

Karl Blossfeldt remains on view at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, until June 14.