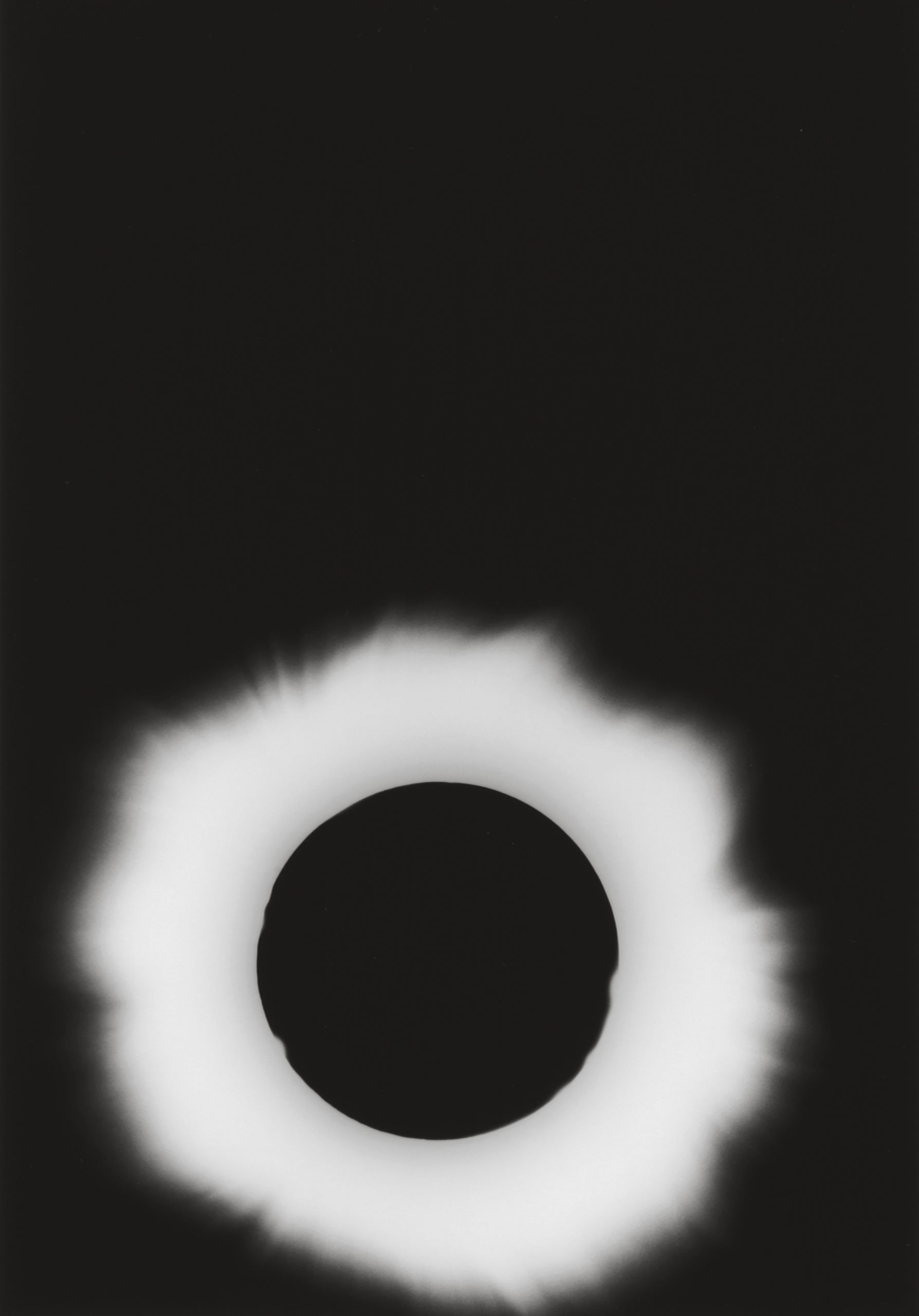

Kikuji Kawada, The Last Total Eclipse of the Sun in 20th Century, Salzburg, 1999

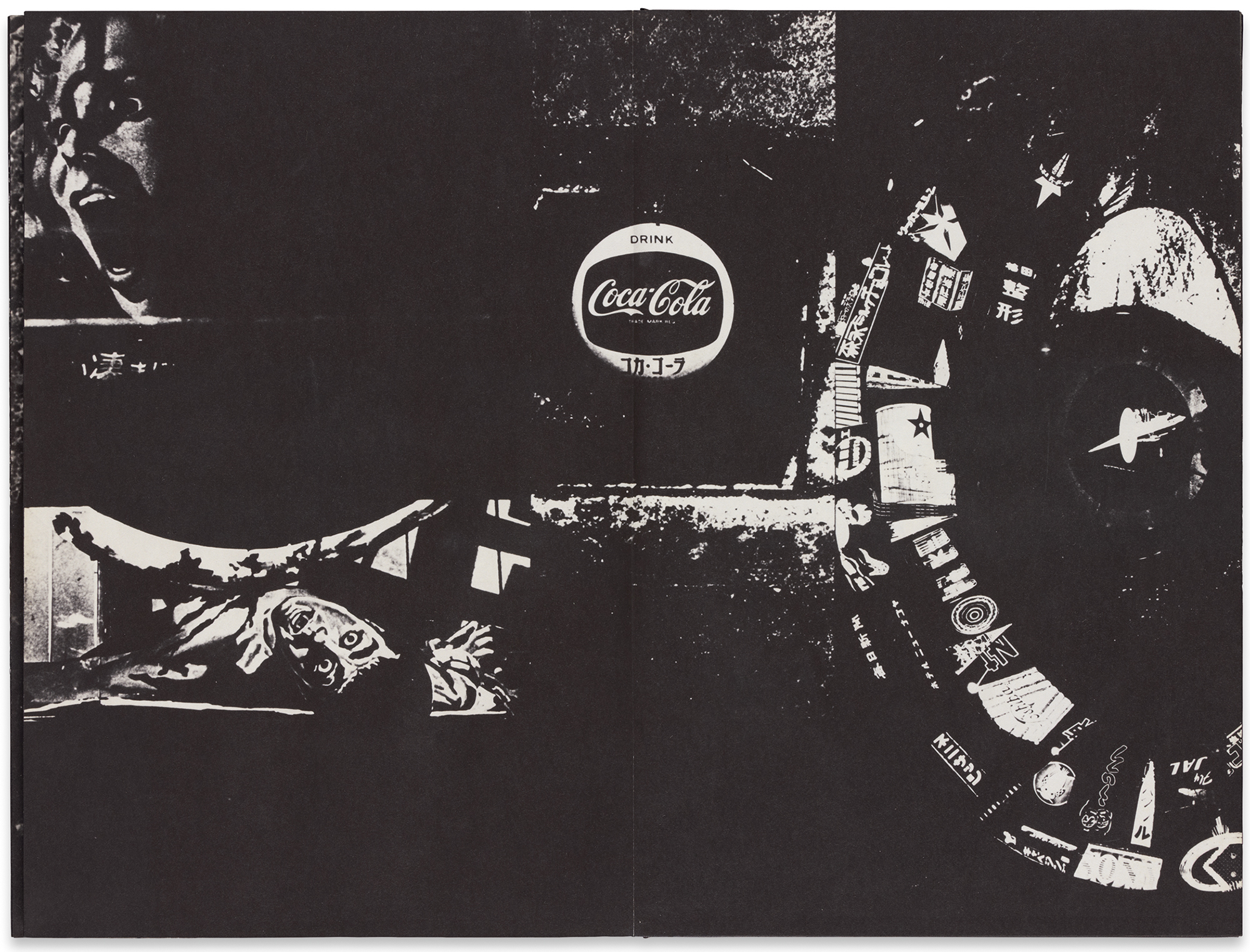

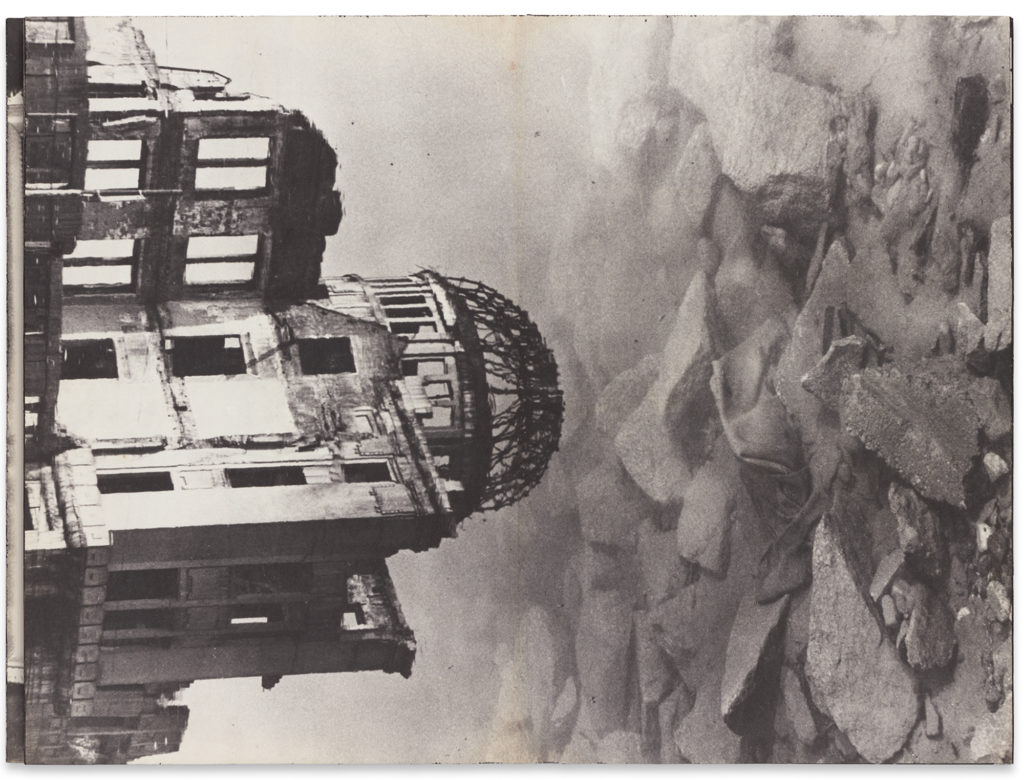

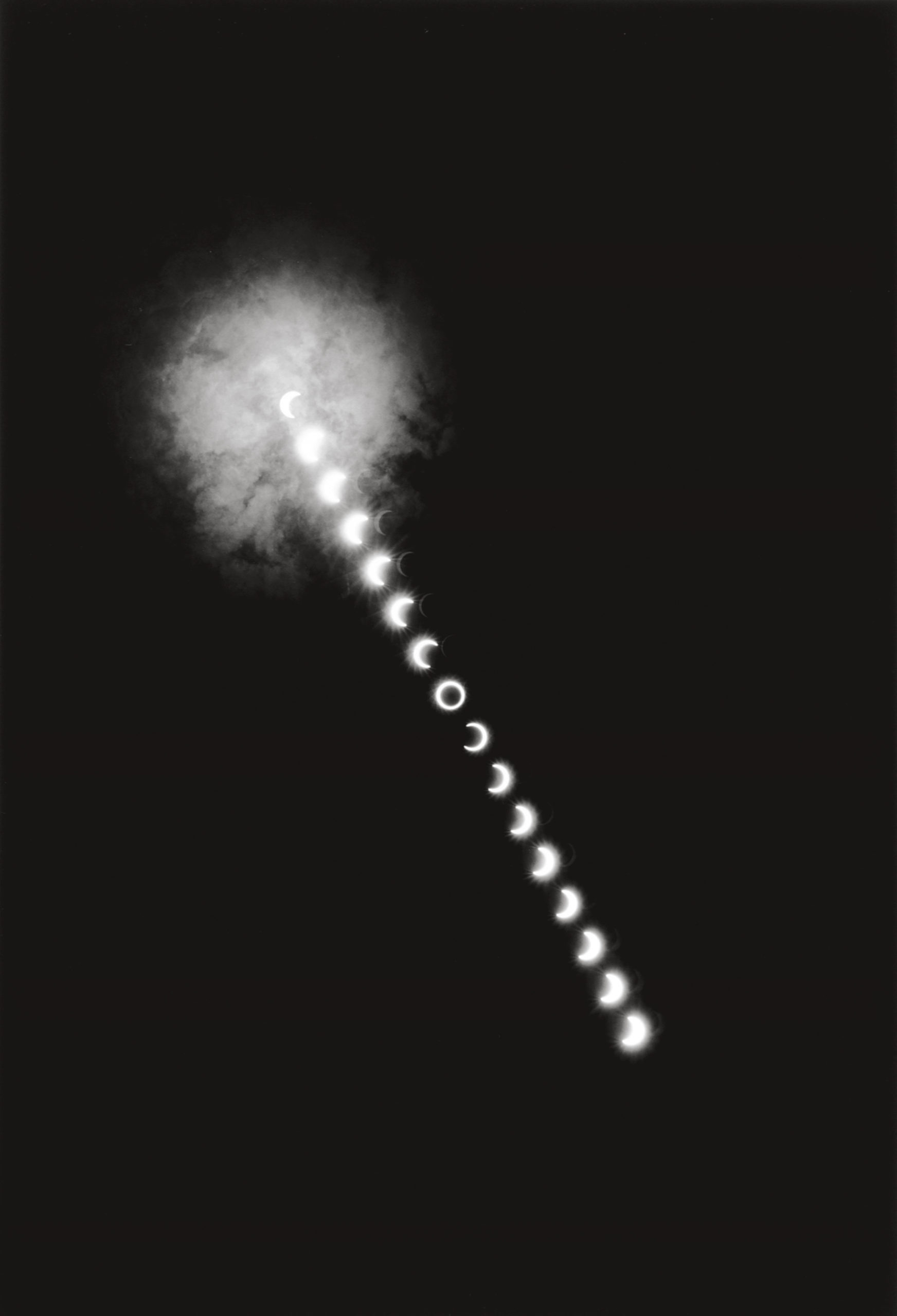

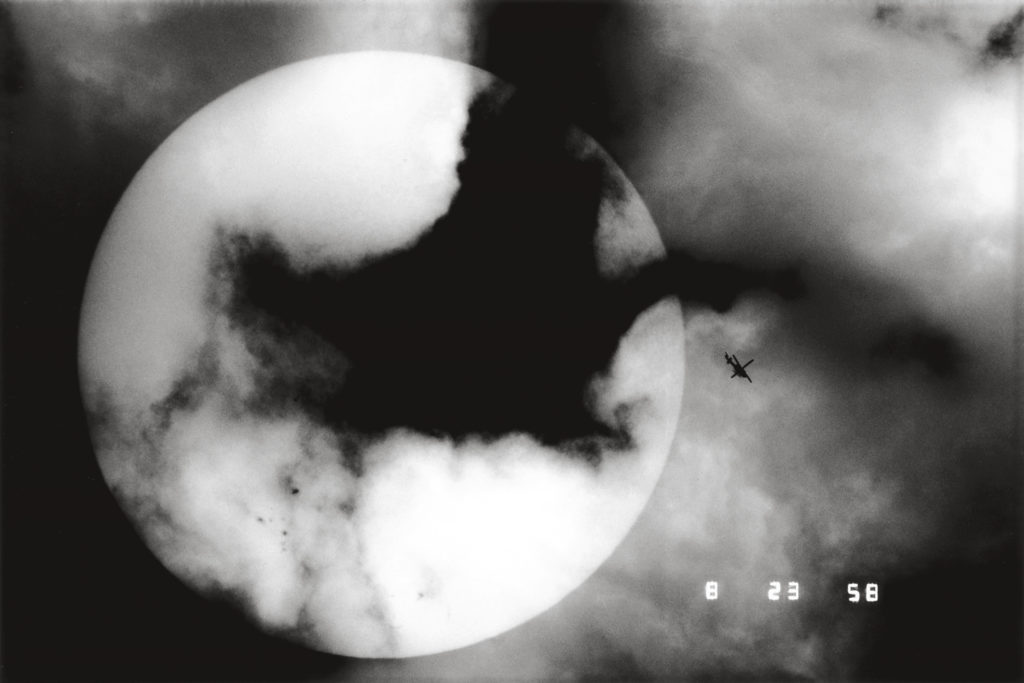

Kikuji Kawada is one of Japan’s most celebrated postwar photographers. In 1959, Kawada—along with Shomei Tomatsu, Eikoh Hosoe, Ikko Narahara, Akira Sato, and Akira Tanno—founded the influential VIVO cooperative, which championed an expressive approach to documentary photography. He is perhaps best known for his now-iconic 1965 book The Map (or Chizu in Japanese), a disquieting exploration of the trauma of World War II. The book, designed by Kohei Sugiura, features images of stains burnt into the walls of Hiroshima’s A-Bomb Dome (now the Hiroshima Peace Memorial), as well as images related to the iconography of the American occupation. Kawada’s subsequent projects continued his interest in connecting the present with historical touchstones and shift between realism and abstraction; some observers have aptly described his work as a form of archaeology. Begun in the late 1960s, his project Los Caprichos (The caprices) was inspired by Goya etchings and features daily life in Tokyo, sometimes with a surrealist twist. Last Cosmology (1969–2000) focuses on the relationship between the terrestrial and the cosmic, capturing astronomical phenomena—solar eclipses, dramatic cloud formations, and the movements of the heavens—often above Tokyo.

Kawada, now eighty-two, continues to attract a wide international audience. His photographs were featured in the 2014 exhibition Conflict, Time, Photography, curated by Simon Baker, for London’s Tate Modern, and MACK books has recently released a volume of The Last Cosmology. For Aperture magazine’s 2015 issue, “Tokyo,” Kawada met with Ryuichi Kaneko, an influential historian and a major collector of Japanese photography books, at Tokyo’s Photo Gallery International. They discussed the arc of Kawada’s six-decade-long engagement with photography.

Ryuichi Kaneko: I’d like to start by asking what made you become a photographer. What inspired your first forays into photography as an art?

Kikuji Kawada: People ask me all the time what made me decide to be a photographer, but I have to say, I’ve always found it hard to put my finger on it. It was more like one thing led to another, really. I got my first camera in high school. The first time I used it, I got on my bike and rode way out into the mountains, out where no one was around, and ended up taking pictures of some dry grass I found out there. Thinking back now, I have no idea why I did that.

I was born in a little town called Tsuchiura—really rural. You could get on your bike and end up in the mountains right away or wander around amid the rice fields.

Kaneko: Most people think of a camera, first and foremost, as a tool for taking pictures of those closest to them. But your first instinct was to go out where there weren’t any people at all.

Kawada: I liked doing things in secret—maybe not the healthiest predilection, now that I think about it [laughs]. I was interested in playing with mechanical things in secret; it felt like I was accessing the heart of the mechanism that way, its essence. Discovering its secrets.

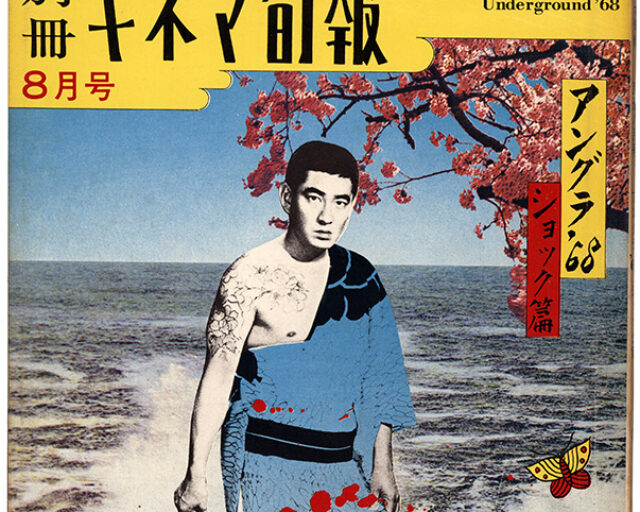

Kaneko: In the 1950s and ’60s you published frequently in photography magazines; Shincho Weekly, Nippon Camera, and Photo Art—those magazines were your mainstay. Looking back at the photographs you published early on— Yaizu and Fishing Port at Yaizu (1957–59), or The Bar Abandoned by the Boom (1957), or even, to a certain extent, the Base photographs (1953)—did these first run in Shincho Weekly?

Kawada: Many photographs were taken for magazines but didn’t end up published. They were too strange. Shincho Weekly wanted less edgy themes for the spreads— though some were things I shot on my own time, when inspiration struck. I would stop to shoot something on the way back from an assignment, for example.

Kaneko: [By the late 1950s] you’d become a member of the postwar generation of photographers, and your work was getting a fair amount of attention. But there’s one series I really must ask you about from this time: when you went to Hiroshima. That was with Domon, right? [Ken Domon, the influential documentary photographer of this period.]

Kawada: It was. I’ve talked about this ad nauseam over the years, but long story short: I proposed a trip to Hiroshima to the editorial board of Shincho Weekly, a documentary shoot, and it was approved. I was excited at the prospect of going, but it was decided that it would have to be a special issue, and in that case it should be Domon who went. That was an order from the top. So, my hopes were dashed in an instant. The people who ended up going were Domon and [freelance journalist] Daizo Kusayanagi. They were charged with gathering evidence under the auspices of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission. It became a huge special issue. And Domon ended up going back and forth to Hiroshima many times during the process of shooting what would become the book Hiroshima (1958). The editor at Shincho was paying for these trips out of his own pocket, and at one point he said to me that he knew I’d been the one to propose the project but that I’d never gotten a chance to go, so he was going to send me along as an assistant. So, it was as Domon’s assistant that I ended up going. That was my first trip to Hiroshima.

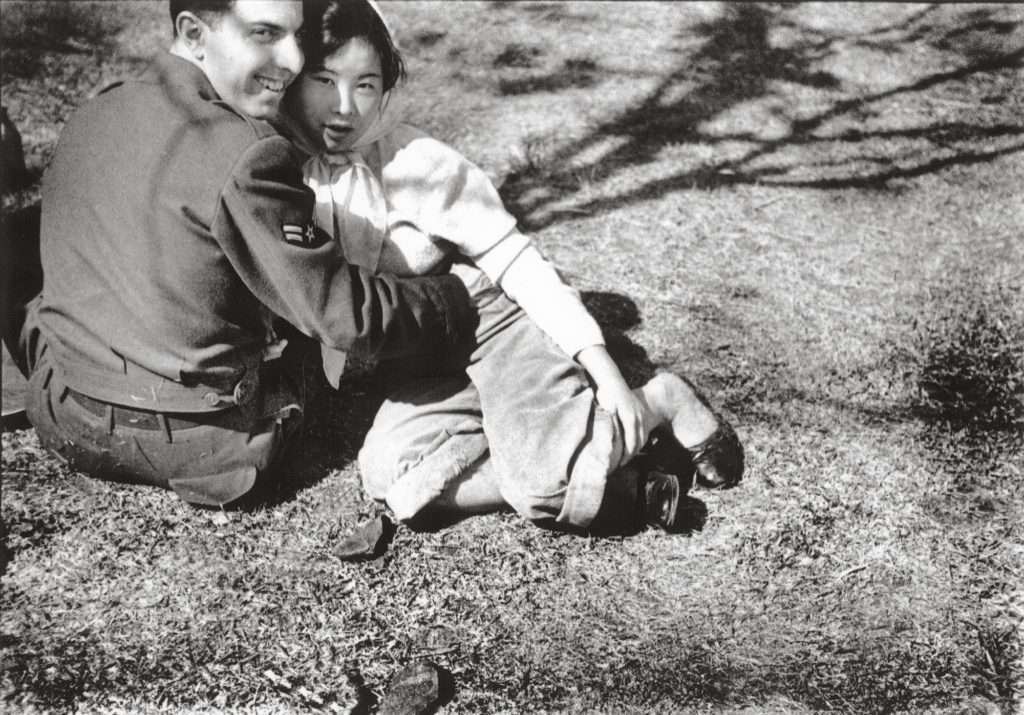

Courtesy the Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

Kaneko: How many times did you end up going with him?

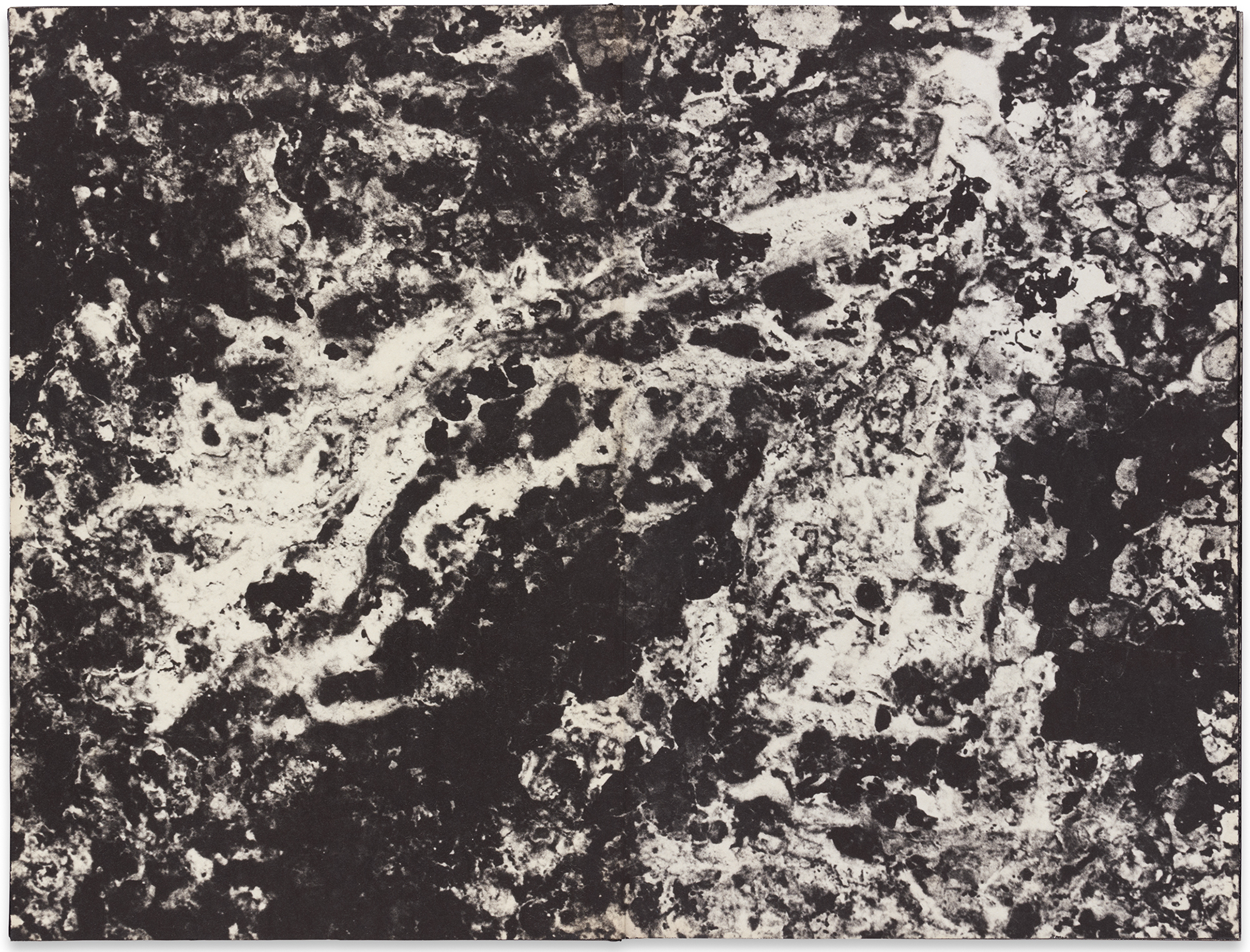

Kawada: Just once. Domon liked the finer things. He wanted to stay at the very best place in town, so we ended up in a new hotel and would walk to the Peace Park and the A-Bomb Dome, which were nearby. We would go together, but then I’d slip away and walk around on my own. And that’s when I found them: the stains on the walls of the rooms beneath the dome that became the subject of the Stain series. I would just slip away, secretly, without a word to Domon.

Kaneko: So, there were rooms underground, beneath the dome?

Kawada: When the place was destroyed, there were about thirty people—I think it was around eight in the morning or so, but at any rate, in the morning—these people had arrived for work and ended up vaporized. The place had a horrible atmosphere. Just looking at it was overwhelming. And you couldn’t see very well; there were no lights, no electricity. So, I left and gathered up a big camera and some bulbs and headed back.

Kaneko: So, that’s how you first discovered that place?

Kawada: Yes. This was going to be my Hiroshima. I could take so many kinds of pictures there. This was no longer assistant’s work; I was preparing my own project. I wasn’t thinking about anything else.

Kaneko: You said you brought back a big camera. Do you mean a 4 by 5? And lights to illuminate the rooms?

Kawada: It was a 4 by 5, yes. But I didn’t use lights; I shot in natural light. Back then, we could go in and out of the dome as we liked. In the Tate Modern book [Conflict, Time Photography, 2014], there’s that famous photograph of Kiyoshi Kikkawa, who was called genbaku ichi-go [bomb victim number one]. He ran a souvenir stand right next to the dome.

Courtesy the Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

Kaneko: I’ve heard you talk before about discovering those “stains” beneath the dome, and when I think about how they may be all that was left of people who were vaporized in an instant, all the hair on my body stands on end. You hear about things like that: people explain what happened as carefully as they can—this happened, that happened, like that. But there’s no comparison to seeing it as one image. It has so much power.

Kawada: The hard part becomes how to organize that kind of material, how to convey its enormity.

Kaneko: You published some of those photographs in Nippon Camera under the title The Map: Stain. That was August 1962. Was that their debut?

Kawada: I think so. After the Eyes of Ten exhibition (1957), there was another show, NON, at the Matsuya Ginza Gallery (1962). I showed many of the Stain pictures there—about ten pieces in all, I think. That was the first time I’d put together a fair amount of them as one exhibition. Eikoh Hosoe debuted the first of his Ordeal by Roses photographs there, too. We had a lot of people coming to that show including Yukio Mishima, of course, since he was Hosoe’s model. I overheard him asking, “What kind of ‘stains’ are these? Stains left by what?” I was a bit contrary back then, you know. I said, “That’s for you to imagine, sir” [laughs]. Though I did think you should be able to tell just by looking.

Kaneko: When looking through The Map, the first thing that makes an impression is of course the A-Bomb Dome photographs—the Stain photos—and then the other images of what you might call “scars of war.” But there are other images, too, like the spiral lathe left for scrap in a factory or a wanted poster related to a heinous crime, or a bank of television screens— all sorts of images. So, history is brought into direct contact with the present.

Kawada: An image taken of the “present,” whenever that is, is so strong—vivid in hue, aspect, substance—because it’s a document. I seek even now to explore new forms for documentary to take. When you layer things in the way we’ve been discussing, the layers produce meaning, metaphors emerge as you go deeper into the juxtapositions that arise, and the ways of seeing the image multiply. Not because it’s a collage, because you have layers, like this [indicates the accordion shape of a camera bellows].

Kaneko: I understand that when it came time to actually make the book, there were a lot of complications on the road from the dummy version to its final form. You were unable to put it out as you first envisioned it, in two volumes, and instead everything had to be layered physically into one volume.

Kawada: That was the plan proposed by our fantastic designer, Kohei Sugiura—to split The Map in two. On the one hand, there were the Stain photographs; they added up to a good proportion of the whole. Then there were the other photographs, the Hinomaru flag photograph, the monuments, the more symbolic stuff. We split these photographs into two volumes—half in one, half in the other—and we’d put them in one case. So, the viewer would have to take them out and look at one volume, then open the other. So, it was only in their heads that the whole “map” ever existed. It was so creative, this idea. But I thought it was too hard to understand. Someone buying the thing would have to realize that he has to look at one volume and then another just to figure out what’s going on. It’s too much trouble.

Anyway, to skip to the end of the story, it was decided that the thing was too big—it would be too expensive—so we had to make it smaller. To make it smaller, we decided it should fold out on every page—Kannon-style [referring to the Buddhist goddess of mercy], they call it, with the hinged doors. Sugiura asked how many pages we should make that way. I thought, if we go that way, we should go all the way. With a triptych, when you fold the sides over a central image, what’s hidden becomes a sacred icon. That’s the meaning of that design—exactly what the Japanese term means, like opening an altar to view an image of Kannon. So, we redesigned every page that way, and it took about a year or so to do it.

Kaneko: The Map came out in 1965, on the twentieth anniversary of the end of the war, and it was talked about quite a bit. Though, I gather it didn’t sell that well?

Kawada: I was afraid it might be passed over entirely, so I took a copy to each publication that ran real criticism. I took the book physically to their offices, right to the writers. I remember one guy, Hiroshi Iwada, the poet. He wrote something in the newspaper Nihon Dokusho Shimbun. And then there was Tatsuhiko Shibusawa [a novelist and critic]; I got him to write something somewhere, too. So, word trickled out like that, and as far as critical opinion was concerned, people thought it was a pretty great thing.

Kaneko: You called the work you did before The Map “symbolic documentary,” Ikko Narahara’s Human Land photographs were eventually called a “personal document,” and Eikoh Hosoe called Kamaitachi a “memory document.” Shomei Tomatsu never used the term, but in the end, it seemed to me that this generation of photographers considered all photography to be “documentary.”

Kawada: We had no strong consciousness of it. I mean, we never debated things in those terms, but I know what you’re saying. Now that I hear you say it, I can’t help but think, Yes, that’s exactly it!

Kaneko: But it wasn’t something you thought about while shooting the photographs. After some time has passed and a bit of perspective is gained, that’s when words begin to emerge. When I try to conceptualize your work as a whole, Los Caprichos becomes key. These photographs were unlike anything that had come before. At first, I was extremely drawn to the work as street photography—the way these photographs seemed to represent a whole new approach to the snapshot. That’s how I thought of them at first, but then, there were suddenly all these clouds. And I thought, What is going on?

Kawada: Well, I devoted my attention to that series for seven years, so all sorts of things are bound to end up in it. So, clouds or whatever, I wanted to absorb everything and then give it shape. Then I moved on to Last Cosmology and more clouds. I shot all sorts of clouds. In truth, I’m still shooting them—violent, chaotic clouds. I’m drawn to things that change, that constantly transform.

Kaneko: This seems different from how you spoke earlier about finding the stains on the wall beneath the A-Bomb Dome and deciding to shoot them—photographing clouds until something emerges from them.

Kawada: Absolutely. It is totally different. Clouds are always changing shape, just as the world itself does. But the A-Bomb Dome? That’s a stain that remains the same; no more will emerge. At a certain point in time, the place was destroyed and it became a ruin. A cloud’s freshness lies in how it’s always becoming something new. That’s the difference. We are a race of seafarers living in an island country, and so for many of us the tides of our hearts move with the tides of the sea. We live enclosed within the sea and the sky. I don’t mean that in an idyllic way; I mean that the face of the world can be found in the changing faces of the sea and the sky, and I’m trying to capture that.

Kaneko: As you gathered the material together to make Last Cosmology, was that a title you used to try to organize these new images, these pictures of heavenly bodies and clouds?

Kawada: Well, at the time, images conjured by words were extremely important to me— the images I saw while reading Gaston Bachelard’s L’air et les songes [Air and Dreams, 1943]. That’s what I had in my head—not the words themselves but the images they conjured. My first title—well, I discarded Dreams—it became just Sky. And then the next series was Clouds. I spent ten years or so on this. The millennium was approaching and the Showa period was reaching its end [with the death of Emperor Hirohito in 1989]. The last annular solar eclipse visible in Showa Japan seemed like a strong image to add to those I’d been collecting. It became a “last” image. But Last Cosmos doesn’t really work, so I made it Last Cosmology. The world of photography had never really produced a cosmology, but in the world of letters, there have been famous histories of the universe and the like, so I borrowed that idea. And that’s how Last Cosmology came about.

Kaneko: And all the while, you kept taking pictures of clouds—other things, too, pictures of the sun, the moon, of Halley’s Comet. Though, these weren’t taken with a regular camera: you used a camera affixed to a telescope to make many of these images. What made you decide to use that kind of specialized equipment?

Kawada: As the themes in my work change, it’s only natural that the mechanisms I use change, too, right? The images I began to want to make, the images that moved me, I couldn’t capture them with a regular camera. I would look through astronomy magazines and be struck by the fact that I would have to use astronomical telescopes and mobile lenses.

All photos © Kikuji Kawada and courtesy Photo Gallery International, Tokyo

Kaneko: When you do that sort of thing, it seems like there’s a paper-thin line between you and a hobbyist looking up in the sky through a telescope and taking photographs. Yet your photographs do seem completely distinctive. Did you think about that as you took them?

Kawada: There is that danger, sure. The danger that if I kept shooting like this, all I’d end up with would be run-of-the-mill astronomy photographs. But, you know, I remained conscious of what was happening on the ground. That’s what saved it, I think. I gave a lecture once and someone asked, “What should I do when I go on a shoot?” Just take photographs, I answered, but [Eikoh] Hosoe—he was there, too—he said something to the effect that it wasn’t enough to just take photographs. He said you had to be searching for something as you shoot [laughs].

Deciding on a theme at the start of a project is an old-fashioned approach, I think. Though I’ve done it plenty of times myself. Later on, I wouldn’t know myself where a project was going; it might split into different projects for all I knew. But if I did it right, it would become something major. Of that I was always sure.

This article and photographs were originally published in Aperture, issue 219, “Tokyo.” Interview translated by Brian Bergstrom.