Kristen Lubben on Zoe Leonard and Cheryl Dunye The Fae Richards Photo Archive

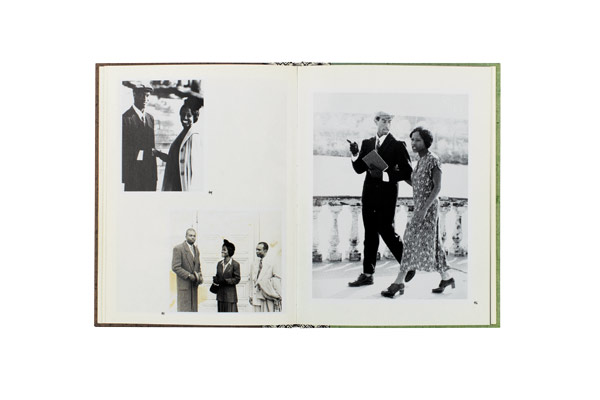

The Fae Richards Photo Archive is a collection of glamour shots, stills from movie sets, photobooth portraits, family snapshots, and typewritten captions that tell the story of a forgotten black actress and singer whose career was sabotaged by racial typecasting, and whose relationships with other women marginalized her even further in mid-twentieth-century America. While eminently plausible, the book (and the character of Richards) are the creations of filmmaker Cheryl Dunye and photographer Zoe Leonard. A fictional archive that could easily have been real, it stands in for women’s lives and stories that surely existed but were never documented. Serving as homage, fantasy, and corrective, this speculative archive challenges the incompleteness of what gets passed down as archive and history.

Zoe Leonard and Cheryl Dunye, The Fae Richards Photo Archive, San Francisco, 1996

The photographs were created in collaboration with Dunye as props for her 1996 film The Watermelon Woman. In the film, Dunye plays a character (also called Cheryl) who works in a video store and is trying to make a film about stereotypical roles for black women in 1930s and ’40s Hollywood. Her research leads her to track down an actress identified in a film’s credits only as “the watermelon woman,” who she discovers was also a singer in butch-femme bars in Philadelphia. Cheryl hunts through the CLIT lesbian archive (presumably a reference to the real-life Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn) and finds a trove of photographs of the actress, who turns out to be named Fae Richards.

This book plays with fact and fiction, artifice and authenticity. It echoes the form of a found notebook, with a handwritten label, a pulp cardboard cover, Fae Richards’s “autograph” on the frontispiece, aged and distressed photographs, and captions typed on an old-fashioned typewriter. Although created to conjure up the golden age of Hollywood, Richards is actually a product of the 1990s and its shifting attitudes about and within the gay community. In the wake of a decade of AIDS activism (Leonard herself was an active member of ACT UP), mainstream acceptance of gay rights was beginning to emerge in the U.S. This growing recognition was attended with some ambivalence: would normalization leech queerness of its radical, subversive potential? Against this backdrop, there was a resurgence of interest in pre-Stonewall-era gay life and illicit bar culture, butch-femme dynamics, and the thrill of an outlaw, underground community—countered by a recognition that the price of that outsider status was repression.

For viewers who have rarely seen themselves represented in official histories or mainstream entertainment, or are represented only as caricatures, Richards’s archive stands in for the lives we know existed but weren’t recorded. Who cares if it is technically fictional? It retroactively materializes a history and a lineage for us that we want and need.

KRISTEN LUBBEN is a curator and the recently appointed executive director of the Magnum Foundation.