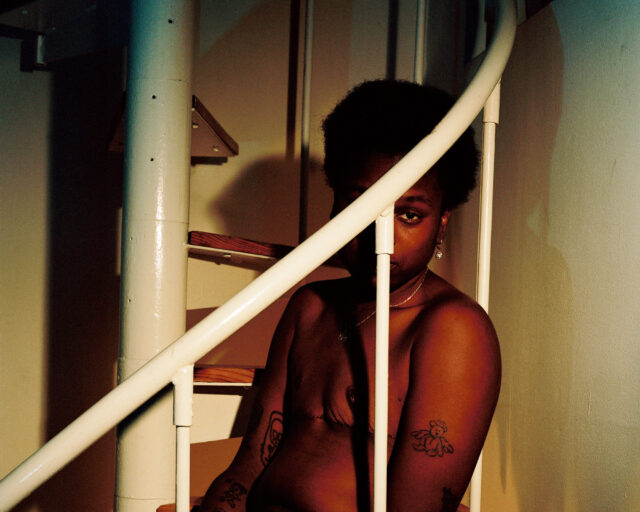

Laila Stevens Seeks Sisterhood in Her Portraits of Black Women

A visit to North Carolina influenced the photographer’s ideas about the power of family.

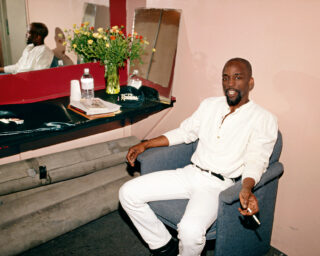

Laila Stevens, Dee-Dee, 2021

When Laila Stevens first drove from New York to North Carolina to visit her extended family on a summer trip in 2021, she was immediately struck by the historical weight of the Southern landscape. “It was my first experience with seeing swampland, plantations, trees that were reminiscent of things that I’ve seen in history books,” Stevens says. “It was very shocking and moving to me—it felt like it needed to be documented.” Shortly after arriving, she took a walk through the swamplands with her sister. Having just watched Gordon Parks’s film The Learning Tree (1969), she instantly recalled the tragic scene in which a Black man is chased into a swamp and shot by a white sheriff. “I had to be able to capture and reference how similar both of these are, this historical scene ingrained in my memory, and this contemporary one that’s right in front of me.”

It was, perhaps counterintuitively, this fraught encounter with the natural landscape that spurred the first images that would evolve into The Clayton Sisterhood Project (2021–ongoing), her series of intimate, celebratory, and powerful black-and-white portraits of Black women and girls in and around the home. As Stevens spent more time with her family in their North Carolina home, ideas around landscape, history, family, and ownership began to percolate. “I eventually realized that it’s really important to have these natural references, especially as Black people have not always had the authority or the economic power to acquire land,” she says. “In contrast, all of these domestic images show people able to take economic power through the ownership of space—having the power to decorate, create safety inside, and being able to gather, speak, and tell stories.”

Stevens, who was born in Queens and now lives in Brooklyn, studied photography at the Fashion Institute of Technology, where she initially struggled to reconcile her images of her family with the images she was making back in New York. Over time, as she continued to photograph the women around her, she found that the concept of “sisterhood” was a central, unifying factor. At first, this concept had a more literal application, as Stevens staged portraits of her relatives in Queens and North Carolina. As the project progressed, the term “sister” expanded to include people who identify as femme or women, and to signify a broader sense of relational bonding between women. “A lot of my friends identify as queer or lesbian, and discovered that we were creating our own form of sisterhood and family bonding that I wanted to memorialize in portraiture,” she explains.

Stevens cites as influences the work of Gordon Parks and Carrie Mae Weems as well as portraits of Black women writers from the 1980s. In photographs of June Jordan by Gwen Phillips or Ntozake Shange by Martin Reichenthal, Stevens found the sense of admiration, veneration, and softness that she wanted to achieve. “There’s also an image called Sister Love by Jim Alexander—a group photograph of Gwendolyn Brooks, Toni Cade Bambara, Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, and others—that I love,” Stevens says. “I’m looking at both the visual aspects of positioning in collective gathering, but also the emotional sincerity of these singular moments that are all emphasized by the soft light.”

In Ibtisam & Momma (2023), a young woman in repose confronts the camera, lit softly by the ambient light of the living room, while Stevens’s mother looks on, silhouetted in the background. The authority of the subject’s gaze, the intimacy of the domestic scene, and the suggestion of intergenerational kinship codifies the wonderful sense of reverence, respect, and tenderness that is emblematic of Stevens’s work, where sisterhood is both the subject and the method of making. “I want to allow a sense of authority for the women in the images who might not otherwise have a sense of authority in the world,” Stevens says. “Despite social implications or perceptions, they’re looking into the camera, they’re looking at the person and saying, This is me, this is who I am, this is my family.”

Courtesy the artist

Laila Stevens is a runner-up for the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.