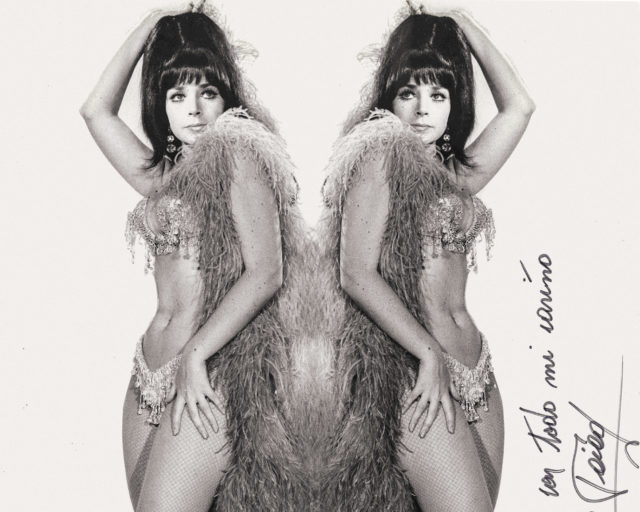

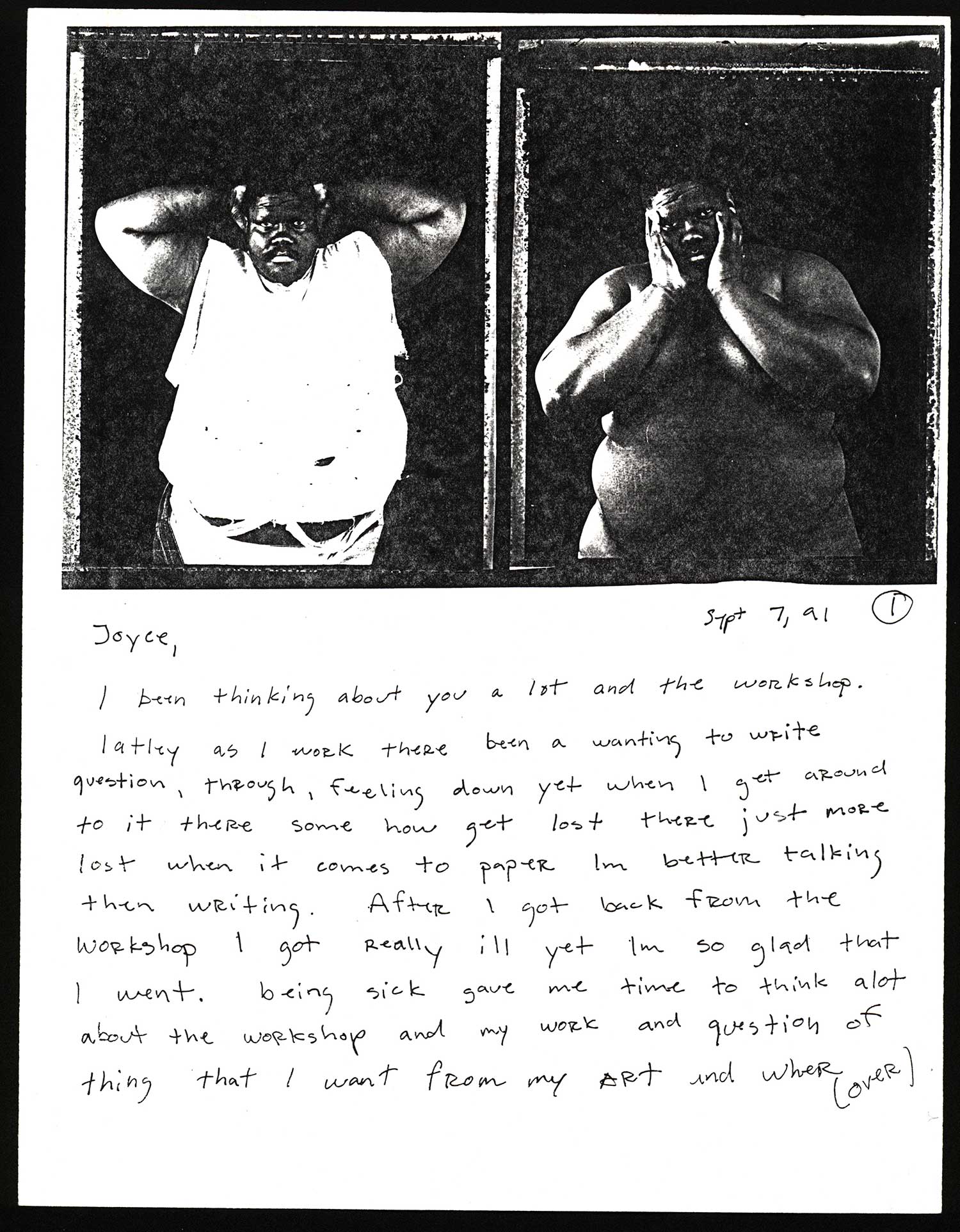

Laura Aguilar Was a Proud Latina Lesbian, and She Flaunted It

What do the late artist’s emotional photo-text letters reveal about the craft of self-expression?

Laura Aguilar, (Detail) Personal letter to Joyce Tenneson, February 22, 1993

In September 1982, then-twenty-three-year-old photographer Laura Aguilar wrote a letter to her teacher and mentor Suda House. “Im not sure do you feel or do you learn how to feel?” she wondered, “And went you learn how to feel is that really how you feel or is it what you learn? Went your not sure about your feelings or how you feel about people and things. How do you know what you feel and what you think you feel is how you feel? How do you learn to understand things you don’t understand?”

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

This letter, along with a large cache of others, is stored today in Stanford University’s Special Collections, which houses many of Aguilar’s papers and ephemera. In these and other documents, Aguilar expresses her anguish over her perceived inability to understand herself and other people, and over whether others could understand her. They form a key part of Aguilar’s oeuvre, as they document emotions and practices that would help shape a critical phase in her artistic development. From roughly 1988 to 1993, Aguilar became one of the most radical innovators of “photo-text,” a style that she embraced in order to confront her anxieties about being overlooked and misconstrued. Aguilar experienced auditory dyslexia, which caused her to write in a unique style; she also wrestled with fears of misunderstanding and being misunderstood as a consequence of her Mexicanness, her lesbianism, her large physical size, and her poverty. Together, the letters constitute a feminist photobook, detailing Aguilar’s interior life and marking her as a photo-text pioneer.

Laura Aguilar was born in 1959 to Mexican American and Irish Mexican American parents; she was raised with her older brother Johnny in the Los Angeles County neighborhood of South San Gabriel. As art historian Sybil Venegas has documented in an oral history, Aguilar formed one of her closest relationships with her grandmother, Mary Salgado Grisham, who often brought her to a local river where they would collect rocks and study the natural landscape. A young girl with a learning disability and a queer identity, Aguilar grew up in a hostile environment, and her parents did not always support her artistic leanings. (The first major study of dyslexia would not be published until the 1960s, and California would not begin to dismantle its anti-sodomy laws until 1976—in 1986, the United States Supreme Court upheld such statutes’ constitutionality, a ruling that lasted until 2003.)

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Aguilar attended East Los Angeles College. There, a teacher told her that she was wasting her time trying to be an artist when she could not even read. Aguilar transferred to Pasadena City College, which had a better program for people with learning difficulties, but she was already experiencing intense feelings about her fraught relationships with language and people. In a 1983 paper that she wrote for a Pasadena composition class, Aguilar confessed: “I don’t know why I even deny the fact that I have a learning disability. I know better than anyone else that I do . . . . All I ever saw was that I am inadequate it hurts to much to admit to anyone.”

People with auditory dyslexia have difficulty processing the basic sounds of language, and the syndrome can result in a strained reading process. In a 2009 study, psychologists concluded that dyslexic people who have issues with self-esteem are more likely to experience emotional and behavioral problems—a perhaps unsurprising finding that Aguilar herself, in an undated videotape titled Work In Progress, commented on in blunter terms: “No matter how hard I try I can’t prove I that understand things in a way that you need to in this society. . . . when you’re at a function and people have nametags on and I’ve met them before and the nametag’s right there and I can’t read it, and I hate myself . . . I want to die.”

What is surprising is that a person with this fractured rapport with writing would choose to incorporate text so prominently into her artwork. In 1987, Aguilar embarked on her Latina Lesbians series, a suite of black-and-white portraits of queer Latinas framed by large white margins that contain notes written by the subjects. Carla Barboza (1987), for example, portrays a fit woman sitting in a wing chair while smoking a cigarette and wearing stylish black boots. Beneath the image, Barboza wrote in clean, black-inked cursive: “I used to worry about being different. Now I realize my differences are my strengths.” Similarly, in Cookie (1987), we see a dramatic, curly haired woman clutching her chest. In exclamation point-inflected script, Cookie inscribed: “I am a proud Latina Lesbiana and I do flaunt it.”

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Aguilar incorporated writing into her art even as her reading problems made her feel “inadequate” and suicidal; this choice creates tension and even mystery in her work. In May 1987, Aguilar offered some insight into her methods in a letter to photographer Jim Goldberg, who created the landmark series Rich and Poor (1977–85), black-and-white images of San Franciscans living on either side of the economic divide, with notes written by the subjects. Aguilar’s association with Goldberg indicates his influence on her, but she reflected on her independent motivation for combining words and images in this beguiling passage:

The series is called Latina Lesbian . . . [It shows] a positive image of Latina Lesbian . . . its hard when I have had a lot of years of thinking of myself as being mexican as being negative as being inferior I do feel poud of my culture and who I am but the past and the past thinking and feeling is still around it take time for the hart heart and the bring brain to get together and belive at the same time and truly belive. So the only to say something about being Latina and a Lesbian through photos was to add language.

What was the “something” that Aguilar was trying to say? When Aguilar embarked on her photo-text work, she became part of an artistic heritage radiant with luminaries who joined words and images, such as Goldberg, André Breton, W.G. Sebald, Carrie Mae Weems, Martha Rosler, and Lorna Simpson, to name a few. Goldberg used words and images to humanize economic inequality, Breton did so as part of his Surrealist project (Nadja, 1928), Sebald to confound his readers about the nature of reality (Emigrants, 1992; Austerlitz, 2001), Weems to punctuate atrocities committed against Black people (From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995; Colored People, 1989–90), Rosler to reflect on photography’s inadequacies (The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, 1974–75), and Simpson to narrate her complex studies of the Black female experience (Necklines, 1989). Aguilar’s letters underscore that she pursued the marriage of script and photo to fulfill social projects akin to those of Goldberg, Rosler, Weems, and Simpson—she engaged photo-text to bring the heart and the brain together to generate positive images of her sisters.

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Still, Aguilar’s letters unveil such a thrashed relationship with written texts that they offer proof that in making this work, she tried to smash public stereotypes but simultaneously strove to cope with very private harms. In connecting her beloved photography with the threats of written script, she hurtled toward the very thing that she feared would destroy her.

In 1990, Aguilar wrote a letter to her close friend Pat Martel, in which she described how she felt: “lest then [less than]. . . knowing that to pick up a book and to be ably to read it and . . . knowing that I have this Lim A ta tion that stop me that eat at me and that at time turn into hate.” In January 1992, Aguilar sent Martel another letter, written on glossy photo paper and illustrated with ghostly images of stone angels from her ongoing Cemeteries series (1990–96): “I felt like killing myself again Im anger cause what made me get out of this place was cause I had to fight again deg deep? [dig deep] my feet down and fight Im anger for always having to fight for myself.”

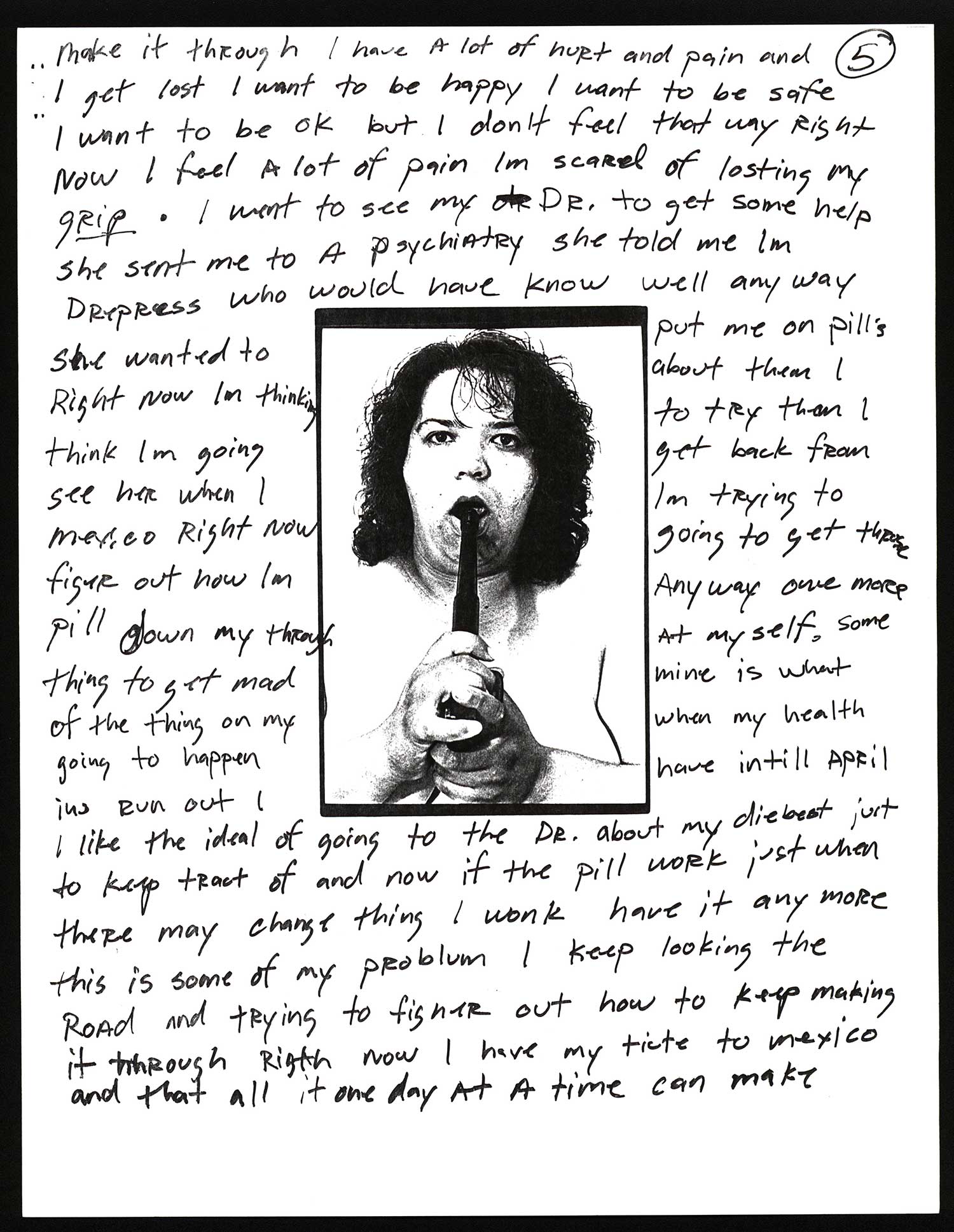

Aguilar’s torment certainly did not come solely from reading problems, but also from her poverty and health. In 1991, she was diagnosed with diabetes—which would kill her in 2018. She suffered intensely as a result of the deaths of her mother and brother, and, as her later work would show, of her feelings of invisibility in the art world. (Her doctor prescribed helpful antidepressants that she feared would be taken from her when her insurance ran out.) Aguilar used letters as a laboratory to express her rages in the language that she both loved and feared, and to see how her writings paired with her images. As her friend and estate administrator, photographer Christopher Velasco, remembers: “Laura told me that her Letters were her way to express herself because it was so hard to explain to people in person, because she was so shy to say it in person. It was another way to showcase her work to her friends and artists she admired.”

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

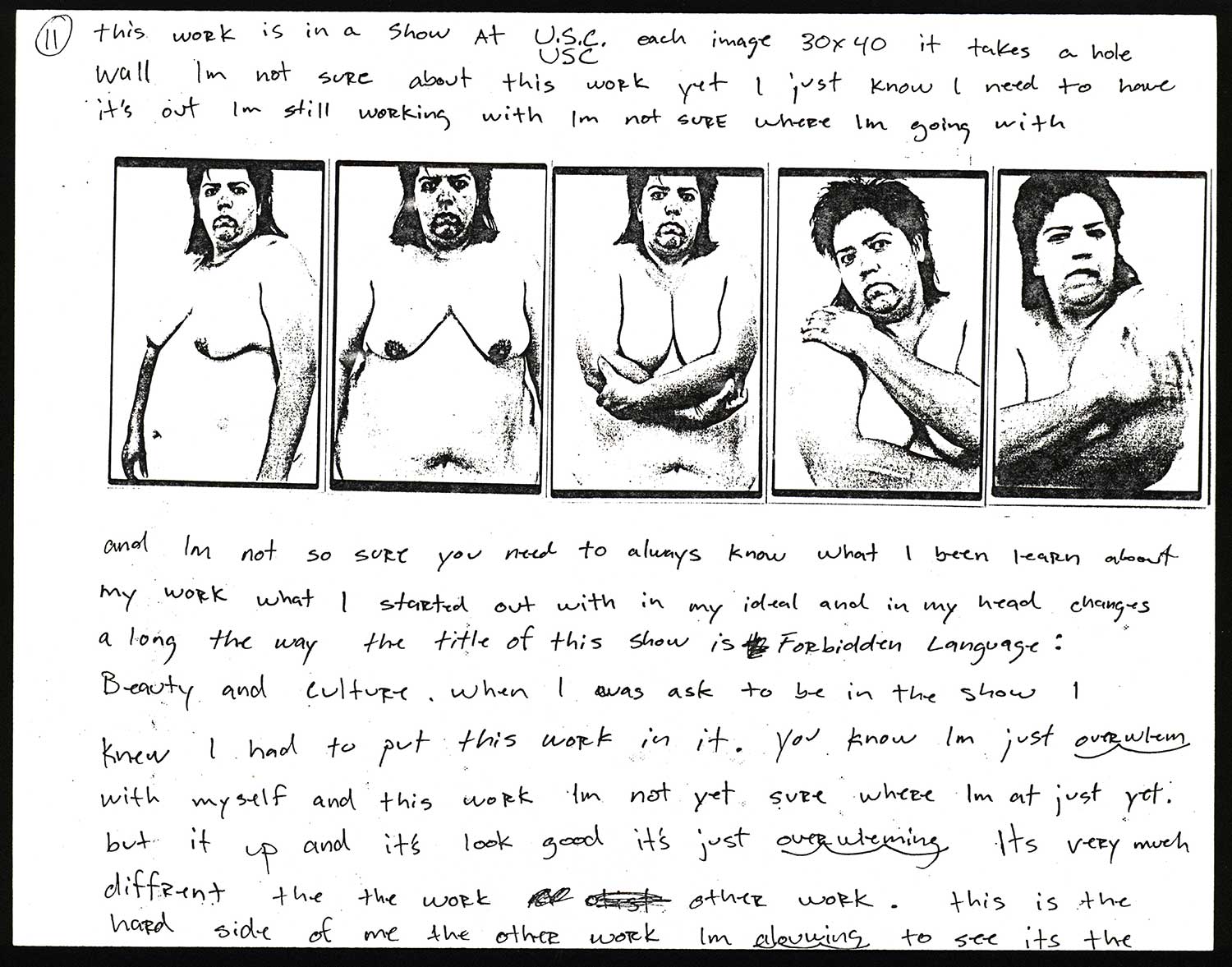

Aguilar’s most famous photo-text work may be her incendiary four-photo series Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt (1993), which shows Aguilar brandishing a gun; as the pictures progress, she removes her clothing and sticks the barrel into her mouth and closes her eyes. At the bottom of the photos, she wrote a narrative about being shut out of the art world: “The believing can pull at one’s soul. So much that one wants to give up.”

But these photos had an earlier airing—as illustrations in an October 1992 letter to Martel. Here, Aguilar told the story of how, at the opening of her group show at the Santa Monica Museum of Art, a rich white woman insultingly ignored her. These feelings of inaudibility developed into a more generalized anxiety that motivated her to pantomime her own suicide: “I feel a lot of pain Im scared of losting my grip.” Her handwriting sprawls all around the pictures. The letters engage a propulsive use of text to underscore both Aguilar’s feelings of fragility as well as her talent for leveraging her supposed weaknesses into unforgettable representations.

The letters and essays that Aguilar wrote from the early 1980s until the mid-1990s show her contending with intense mental suffering, both caused and expressed by language. In Latina Lesbians and Don’t Tell Her, and in the letters where she practiced photo-text, Aguilar dealt with her fears and her disability at the same time. They are acts of survival, experimentation, and courage. But at some point, Aguilar had a breakthrough.

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

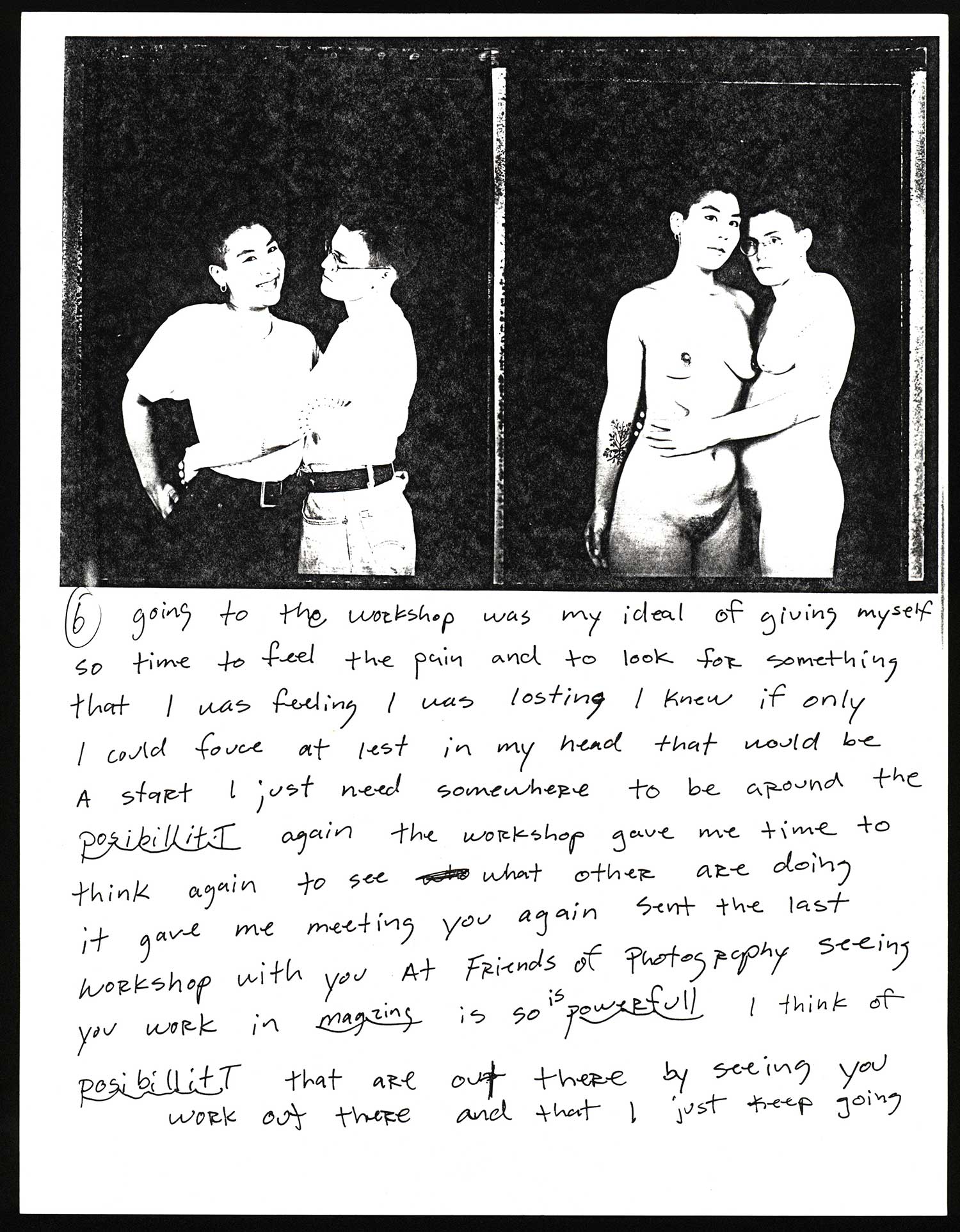

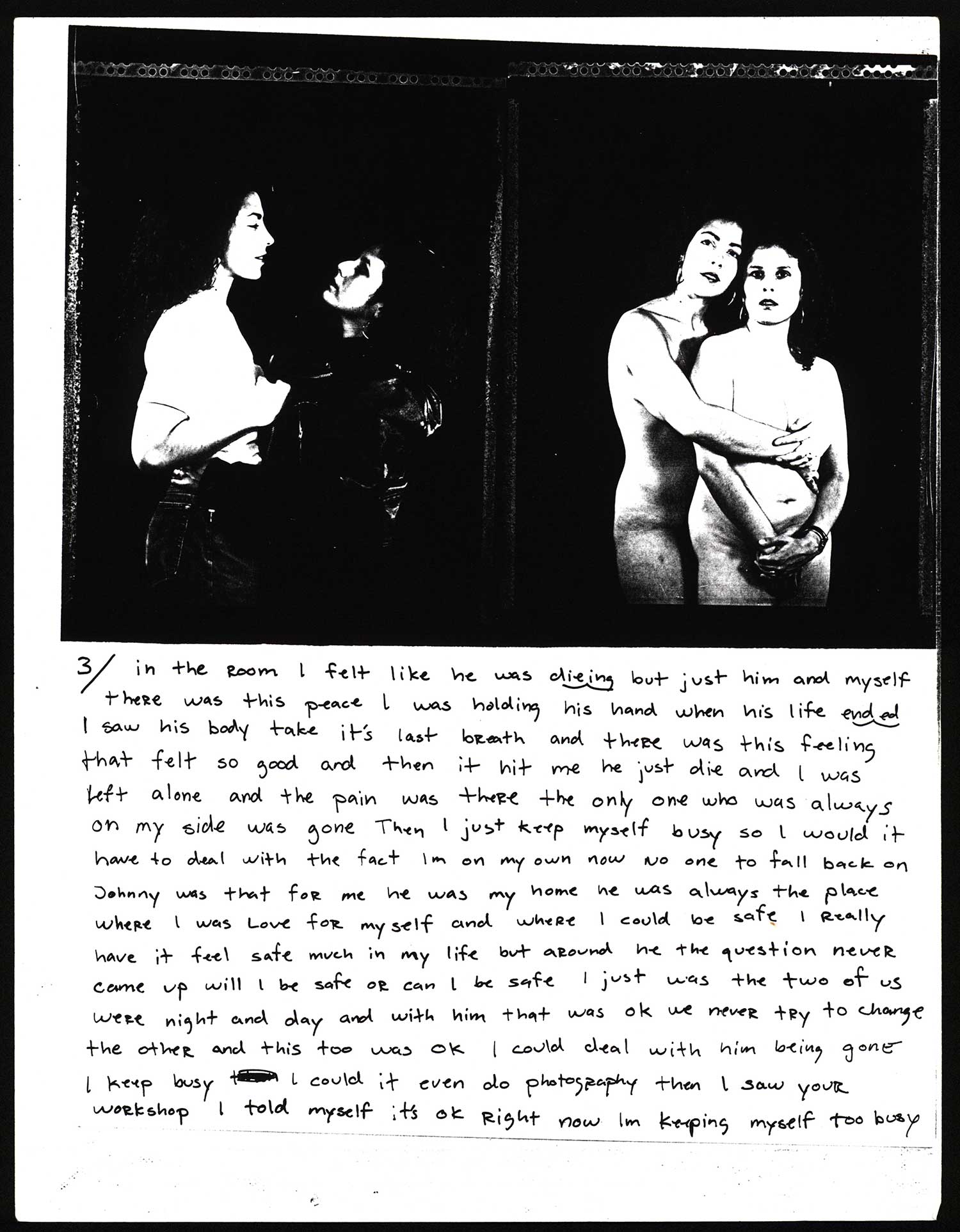

In a November 1993 letter to photographer and teacher Joyce Tenneson—which Aguilar illustrated with more images from her Cemeteries series—Aguilar wrote about her burgeoning work with nude self-portraiture, which began around 1990. During this process, Aguilar began to feel differently about herself:

I think a lot about why I photograph myself nude I know it started at a place of shame . . . before I don’t think I really every look at myself no one else look at me notice me so I just pick up that I don’t exist. . . . Now somedays I find myself just standing there looking at myself naked in front of the mirror thinking, looking to find something new to photography and there come this big smile on my face and I think yes you are crazy and its ok.

It would be too much to say that Aguilar’s work with nude self-portraiture created an immediate transformation that allowed her to freely read herself. Nevertheless, the feelings of self-acceptance and happiness that she first began to experience during these sessions later blossomed into her series Clothed/Unclothed (1991–94), which shows lovers and families in states of dress and undress.

These later branched into masterpieces, which depict Aguilar nude in the natural landscapes that harken back to her riverside musings with her grandmother—Nature Self-Portrait (1996), Stillness (1999), and Motion (1999). The photographs reveal Aguilar and her friends wandering loose and exultant through the deserts and woods; they are very beautiful. These images contain no text at all.