Are You Listening, America?

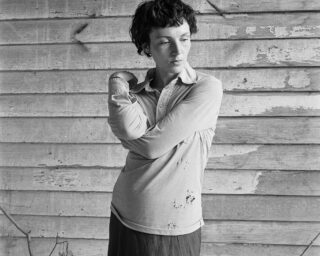

Adam and Samantha outside their home from Thy Kingdom Come, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Eugene Richards always pays attention, close attention, while stealthily drawing almost no attention to himself. His countertenor voice floats or pitter-patters slightly above a whisper. He’s tall and lanky, yet seems to take up almost no physical space. His serene demeanor belies an explosive intensity. His instincts are those of both predator and prey—the one who hunts for the stories, and the one who has seen too much, and thus emanates a vulnerability to which people relate, respond.

And he knows this country and its people—“Americans We,” as he titled one of his books—having spent much of his life documenting from America’s heartlands to its peripheries, its blue-collar and most down-and-out neighborhoods, its industrial landscapes and its institutional landscapes—hospitals, jails, and the like. He engages. Always. Conversing, photographing, and on some occasions filming and videotaping those people he meets with a story to tell. Curious? Absolutely. But also aware of the efficacy of keeping a record, bearing witness—his own record, his memory, having been irreparably damaged after he was brutally beaten by likely Klansmen, when he lived in Arkansas (from 1969 to 1972).

Born in 1944 in Dorchester, Massachusetts, Richards made his hometown and its people an early focus in his book Dorchester Days (1978). But that came after his time as a VISTA volunteer health worker in Arkansas’s Mississippi River Delta, after which he became a reporter and social worker in Eastern Arkansas. There, he and other ex-VISTA volunteers founded RESPECT, which helped organize and distribute food and clothing to the poor. Out of this work evolved his first book, Few Comforts or Surprises: The Arkansas Delta (1973). Later, at the request of his then wife, the writer and poet Dorothea Lynch, who was dying from breast cancer, they together chronicled her illness and created the book Exploding into Life (1986). Its disquietingly poignant texts (hers) and images (his) revealed cancer’s physical and social realities long before the disease was openly discussed as it is now. Only a few years before, they had collaborated (again, Gene’s images, Dorothea’s writing) on 50 Hours (1983), a book that experientially moves through illness, protests, births, and other life events occurring mostly in Seabrook, New Hampshire. In other words, from the beginning, Gene has intimately focused on issues of social justice and health that challenge America and its citizens.

Eugene Richards, Final treatment, Boston, Massachusetts, 1979, from the series Exploding into Life

Courtesy the artist

He continued with Below the Line: Living Poor in America (1987), and then came his riveting coverage of Denver General Hospital’s emergency room in The Knife and Gun Club (1989). Gene’s portrayal of the drug scourge in inner-city America, in his devastating Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue (1994), was a scathing indictment, through interviews and images, of our so-called “war on drugs” and its accompanying slogan, “Just say no.” Recognizing both the uselessness and the ultimate indifference of such inept policy, the book instead examines how crack-cocaine addiction ultimately destroys the very fabric of disenfranchised, vulnerable communities, and must be addressed in terms of this, and the poverty from which it emerges.

Myriad magazine stories (many collected in The Fat Baby, 2004) and other book and film projects consider everything from river blindness to mental illness (A Procession of Them, 2008) within and outside of the US. His stories embrace individuals of all races, genders, ethnicities, and ages, including two films on the elderly—Clarence, a Nebraska farmer, and Melvin, a farmer in North Dakota, respectively—in But, the Day Came (2000) and The Rain Will Follow (2016). Gene’s searching book Stepping through the Ashes (2002) evokes the ghostly World Trade Center site soon after the horrors of 9/11. There, he photographed while his wife and partner on many projects, film and print producer Janine Altongy, interviewed first responders and others. War Is Personal (2010) contemplates the excruciating toll of the war in Iraq on those who fight, and on their families at home—again through images and interviews. The story side of war becomes even more prominent in his 2015 play, In a Far Away Mind.

Eugene Richards, Still House Hollow, Tennessee, 1986, from the series Below the Line

Courtesy the artist

Gene has a habit of making work that defies categorization, and is often prescient in form and/or content—as is the case with his new film, Thy Kingdom Come, which will have its world premiere at Austin’s SXSW Film Festival on March 10, 2018. Begun in 2010, the film questions the very nature of documentary. The cast comprises individuals from the town of Bartlesville, Oklahoma, as themselves, and an actor: Javier Bardem, in character as a priest, yet most essentially himself. The film opens in such a way that announces its conceit.

Visually, it is quintessentially Eugene Richards. Camera angles, at times askew, intensify the raw intimacy of what we are experiencing. Ambient light conspires with the layering of images. Stark contrasts resonate with stark truths. Windows and mirrors compositionally and metaphorically play with transparency, opacity, and reflection. Shadows seem to have matter, and the tangible—a hand, a cat—feels almost illusory.

It turns out that the people who Bardem and Gene meet and speak with in the no-longer-thriving oil town of Bartlesville, home of Frank Lloyd Wright’s only skyscraper, are desperately hungry for someone to talk to. This has always been Gene’s forte: sensing where the stories are and then, of course, how to tell them. Trusting his gut, he has often been led by his assignments to experiences entirely unanticipated when he began. Such is the case with Thy Kingdom Come, which all began with Terrence Malick and To the Wonder (2012).

Ben Affleck and Javier Bardem in To The Wonder, 2012

Courtesy Magnolia Pictures

Melissa Harris: What is the genesis of Thy Kingdom Come?

Eugene Richards: It was in 2010, so it’s tough to remember exactly, but the first call was from Nick Gonda, Terrence Malick’s producer. He asked me if I wanted to be involved on a film with Malick. Terry and I had met briefly in the 1990s and I loved his film Badlands (1973), so I was very honored to be asked to be a part of this. At the time of Nick’s and my first conversation, the film was untitled and the script not something to be discussed—except that one of the characters, to be played by Javier Bardem, would be a priest experiencing a crisis of faith, and a lot of it would be set in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, where Malick in part grew up.

As part of this film, their idea was to incorporate real people, local townspeople, in scenes interacting with the parish priest, Javier, in order to give the film a broader sense of reality or atmosphere. These were meant to be short scenes shot on video that might later be edited into the final work.

Harris: When did you first go out to Bartlesville to scout, to find your subjects?

Richards: I first went in August 2010 on a kind of research trip and met Father Lee Stephens, Bartlesville’s Episcopal reverend, who said he would introduce me to people he knew who he thought might be interested in speaking with us. That’s how we began to meet people.

Father Lee was a really good guy, very interested in social justice, and in association with his Episcopal parish, he ran a program focused on helping those struggling economically and emotionally. Father Lee had this great term—“future story”—that he used when talking to people. His idea is that there’s no point in always dwelling on the past. He tries to help them know that there is the possibility to get their lives under control. This was a big part of his ministering.

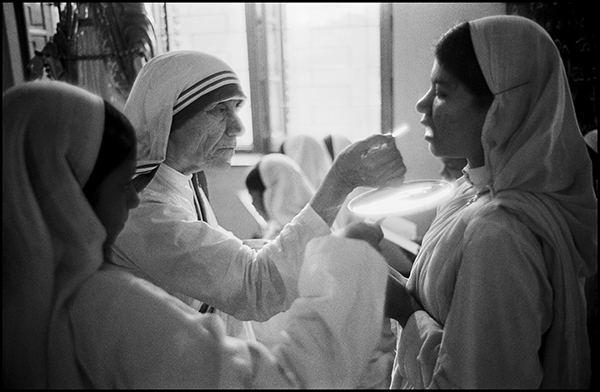

Mary Ellen Mark, Mother Teresa giving communion in the Mother House, Mother Teresa’s Missions Of Charity, Calcutta, India, 1981

© the artist

Harris: Did Malick have a clear idea of what he wanted his priest to be like—both his fictional priest (played by Javier Bardem) in To the Wonder (2012), and then what he was hoping to get from your footage with Bardem?

Richards: Terry Malick very much liked Mary Ellen Mark’s Mother Teresa photos . . . He, in fact, lent me one of her books. He thought a priest should act in the hands-on manner of a Mother Teresa—at least the one pictured in the photographs. But I had to tell him about what I had actually seen, for example, when I photographed in the emergency room in The Knife and Gun Club (1989). The priest would have to come in and talk with the person while they were critically ill and talk to the families, to find out what their wishes were. That’s what I said to Terry; it isn’t so much a physical thing as it is a listening process. I told him that I saw the priest’s first role as listener—as did Father Lee, as did Javier, in time.

Harris: Did Father Lee interact with Bardem at all?

Richards: Yes. Father Lee was helping Javier to understand the role, what to do with his hands, and other gestures . . . He also spoke to Javier about the prayer book he’d be carrying, the nature of confession, and the last rites, and what might be appropriate passages from the prayer book for such occasions.

Harris: So how did it begin, with the subjects? After Father Lee introduced you to them, or you met others on your own, what happened next?

Richards: Everybody knew there was a film going on in town—they’d heard about it, they’d seen the trucks and all that. Some of them had seen Javier in No Country for Old Men, but most of them had not. Still, everyone knew he was an actor. When we went into people’s houses, we introduced ourselves, and most everyone said they wanted to do it. I said to each person, just be yourself. It’s a fictional film. We’ll just be here for a little while, and there are no instructions about what to do or say. That’s all up to you.

Callie and her son from Thy Kingdom Come, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Harris: What was the camera you used? Thy Kingdom Come feels very panoramic.

Richards: The camera I was using was a very high-quality digital video camera called a RED. And generally we filmed with either an 18 or a 21 mm lens. We would be shooting with an aspect ratio that was quite wide and narrow, something like CinemaScope wideness. The surprise was that the camera was quite sizable, or heavy, for me, since I don’t shoot professional video. And I have almost never used a tripod, so I really didn’t know how to work with the RED on a tripod. I hand-held the camera the whole time.

Julio Quintana, my assistant, insisted that we take a belt and strap the camera to me so I wouldn’t drop it. The wide format, when I looked through it, actually felt quite natural. I thought it was very beautiful, but it’s disconcerting at first because in order to get close to somebody, you have to be literally, quite literally on top of him. Most filmmakers would be far back and then use a zoom lens.

Harris: I bet both your holding the camera—you’re amazingly steady—and your being so close, without tons of equipment, along with the use of natural light, must have also made it easier for everyone to be comfortable with all of you.

Richards: We assumed that people might be self-conscious, that they might stare at the camera, that they might perform, but remarkably, that didn’t happen. Part of this, of course, is due to Javier’s gentle, calming demeanor. Part of it is that we generally kept quiet, proved not to be judgmental, treated people with the respect they deserved. While the priest was fictional, the film is a documentary, revealing simply what happened, with only the smallest bit of direction.

Adam and Samantha outside their home from Thy Kingdom Come, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Harris: Who did you film first?

Richards: It was kind of by chance. I was this stranger, walking through the trailer park, when it was getting to be really hot. It was 104 degrees. I saw a young woman and I waved. She came over and asked me if I wanted a glass of water. She got me a glass of water, and we started talking. That’s how I met Samantha. She had no self-consciousness, she didn’t know I was a filmmaker. Then I asked her if she and her boyfriend would allow me to use my camera. So Samantha and Adam were the first people that I filmed, but without Javier. And the filming was clumsy, as I was learning how to operate the camera.

Then Father Lee introduced Julio and me to Josh. We walked into his house and after some general small talk about what we were doing, about the fact that this was for a film, I knelt down and began filming while asking him questions. There was something very special about doing the interview with this man. It at first raised an ethical question for me, because his children were there. Part of me was thinking just concentrate on the father, because he wanted to, needed to talk. The kids were there watching. I included them because he didn’t chase the kids out. Their response makes it so extraordinary—these kids were so cool. They totally paid no attention to me. They were just playing.

One of the next people I visited was Tasia. She proceeded to tell me that she had lost her baby in a terrible accident. What was clear was that she wanted to tell somebody about what had happened, only five months earlier. When I later brought Javier there, I most probably told him about the loss of a child, since I didn’t know whether he should or shouldn’t bring this up. But she brought it up, told her story, after letting Javier play with her little girl—she has two other children. I think she sensed that all of us would be supportive. Javier quite naturally held her hand. He’s very, very nice. He couldn’t be a more decent guy, and totally without ego, just a gentle guy who knows how to be with people. She told him her whole story.

Basically, that was the process with almost everybody, and in most cases I did meet them in advance of Javier. And they would almost always ask, “What would you like us to talk about?” and I would say, “Anything you want.” Later Javier would say, “Tell me about yourself, if you want to.”

Tasia and her daughter from Thy Kingdom Come, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Harris: He’s so intense, yet simultaneously low-keyed. Was Javier scripted in Thy Kingdom Come?

Richards: No, not a word of it, except for the small introduction that I wrote. He would occasionally, when under stress—and we were all under stress—struggle for words and come up with what sounded like scripted lines from To the Wonder as a kind of default. Most of Thy Kingdom Come was Javier and everyone else being themselves.

Harris: A challenge that he met extraordinarily, despite or perhaps because of whatever unease he may have experienced. He was a bit of a revelation—unscripted and remaining in character—as your subjects, one after the other, opened up to him. I found myself watching him, like I used to watch dancers—where you take note of the most minute gesture. His movements are slow and nuanced, never abrupt. I don’t know if they were intuitive, or if they were almost reflexive, because of his own distress at the intense suffering he was suddenly privy to, but whatever it was felt honest.

Richards: Yes—in part because he is a truly decent man, who is interested in people, so he wanted to listen in that open-ended way. And people will speak when they feel someone is listening.

He was moved, and deeply troubled, by some of the stories we heard—as anyone would be. As it happened, months later he gave his fee for the Malick film to Father Lee and me to distribute to many of the subjects. But this was a personal matter for him.

Harris: When, or how, did you realize that you might want to create something independent from the conversations you were documenting with Bardem, in his role as priest?

Richards: If anything, we realized one by one how significant they were, but didn’t, until two weeks into the shooting, consider that they might together comprise their own possible film. It was then that Javier, my wife Janine (who served as co-producer on Thy Kingdom Come), Julio, and myself kind of went, “Wow.” Javier’s first interest, as I remember it, was in a film quite possibly for film students, in which the differences between reality and performance could be discussed, along with the actor’s process.

Thy Kingdom Come is comprised of video footage that I shot over a three-week period back in 2010 for To the Wonder, but it was only licensed to us this past year. We didn’t see any of the footage while we were shooting except for one day, when Julio and I were not sure that the camera had recorded. But I knew we were getting something unique, that people were telling their stories to us, and that their stories mattered.

Eugene Richards, Doctor after loss of patient, Denver, Colorado, 1987, from the book The Knife and Gun Club

Courtesy the artist

Harris: For a very long time now, haven’t you been interviewing your subjects in conjunction with your photographs—asking them to tell their stories? I’m thinking of those, for example, in your book The Knife and Gun Club (1989).

Richards: Before that was an assignment I received in 1981 to photograph at the Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Lima, Ohio. I had incredible access to the patients and felt the need to know their stories, since many of the people, though rather drugged, didn’t seem to be the people to commit the violent crimes that others said they did. So then I learned by asking questions. The Knife and Gun Club interviews began after the initial magazine assignment in 1980 went nowhere, and I went back to Denver occasionally during the next few years, whenever I had the time and money to do so. And for Below the Line: Living Poor in America (1987), which began in late 1985, Janine was my researcher and producer. We were very aware that the photographs weren’t enough, that archetypal pictures depicting poverty were oftentimes too simplistic.

This is going to sound strange, but I’ve always felt uncomfortable with the silence of the still image. I feel that you’re—when you go into some place, when you are with somebody, you are taking a moment out of a big life. If you’re not careful, you end up looking for the dramatic moment, which can so easily slip into the clichéd moment. What you tend to look for is something revelatory in a large way. In fact, people’s lives are revelatory in little ways. So I just started talking to people.

You realize there’s no way that you can, in a still photograph—no way you can quite grasp either the joy that people have, or the desperation—at least in all its complexity. If I had my life to live over again, it would be as a filmmaker, where you can combine the language and the images much more comfortably in a sense. I never totally trusted images. Sometimes life is much harder than what you see.

The grandmother under the bridge in Brooklyn from Americans We (1994), for example—this is a beautiful scene, and I’m talking to the grandmother and I said, “So this is your family.” She said, “Well, not everyone.” I said, “What do you mean, not everyone?” She said, “My daughter is up there, around the corner.” Her daughter apparently, as I understood it, had an addiction problem . . . so that kind of a thing. That this wonderful demeanor, this sweet, sweet grandmother you see and feel in the photo—well, my picture doesn’t show what’s lurking up there, around the corner. And that’s her real, whole story . . . And that’s the thing about journalism. My picture of the grandmother is not untruthful, but it’s also not the entire truth.

Eugene Richards, Grandmother, Brooklyn, New York, 1993, from Americans We

Courtesy the artist

Harris: I guess by nature, making a photograph is a reductive process; you are focusing on a moment of someone’s life, from the perspective that most interests you. It’s not false. But it’s not, it can’t be, a full picture. So I understand how the addition of their words can help contextually, but I also think you may be selling yourself way short. What in part distinguishes your work are, I think, your visual narratives, your storytelling, your sense of characters—you are never hit-and-run. You linger . . . you let people reveal themselves—at least aspects of themselves—in your photos for who they are, for better or for worse, without judgment. But you’re right in the sense that you are still distilling someone else’s life as you perceive it, and/or wish to render it. Is that journalism? I think so, if we accept that the notion of utterly objective, baggage- and-perspective-free journalism is a false construct. But you are always forthcoming and upfront about what you are doing.

Richards: We all get defensive about what we are and what we’re not. I mean, you want to do something that is just, that is truthful, that matters. Photography to me is like raw instinct. It’s more like the hunter in the woods. Writing, for me, is less intuitive, but involves a different kind of energy and effort.

Kathryn from Thy Kingdom Come, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Harris: The way you filmed Bardem, which is very rarely straight on—you see his hand turn ever so slightly, you see him fiddling with his eyeglasses, you see him from the side, you show his collar, and the black shirt—all this, before you actually see his recognizable face. In your mind, were you filming Javier, or were you filming an actor, or were you filming a priest?

Richards: A priest.

Harris: It’s funny—a “real” priest is also essentially playing a role. The conversations you and Javier invited were not about God, or the Bible, or salvation. They were about as present and real and as human as it gets.

And with Bardem, you have somebody who, as he is listening to and responding to your subjects, in a way becomes a conduit for Thy Kingdom Come’s audience. He becomes the medium through which the interviewees’ answers can be processed by the people watching this documentary. He’s not having big responses. He’s not interfering with their storytelling. And what’s cool is that the tone—in the entire documentary—is not confessional. There are no sins, no absolving or Hail Marys. That’s what makes it so especially wrenching. Everyone seems to be accepting of his or her lot, while at the same time longing for the “future story” offered by Father Lee. There’s no denial, there are no excuses and not one false emotion.

Richards: It’s true, and the tension or the questions about what’s real and what isn’t real—this then adds another dimension. But this is true documentary. We are never asking Javier nor any of the individuals we are speaking with to do anything. There is no direction, except that I strongly suggested that Javier and Julio and I, for that matter, remain as nearly quiet as possible, in order to let people truly say what was on their minds. Nothing is contrived.

Former Klansman from Thy Kingdom Come, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Harris: How did you meet the Klansman? Was Father Lee ministering to him?

Richards: We met the Klansman—Melvin C.—by accident. We were actually looking for someone else. That person had been suddenly evicted from her house and these other folks—Melvin C. and his family—were sitting outside their house across the street.

Melvin was visibly very upsetting to Javier. A one-time Klan leader in Missouri, this guy was talking about being a bigot, about his hatred and prejudice. Javier was pretty taken aback, taking a seat in a room papered with Confederate flags, and there may have been a swastika in the corner. But he worked to become the priest and the listener, rather than let his feelings show. But then, of course, his feelings began to show. And I was there to offer up an off-camera question, when needed, and an occasional hand on Javier’s to calm him. I think the thing that disturbed Javier the most was how very up-front Melvin was. There were excuses offered, but little was hidden, and usually such bigots stay in the dark.

Harris: On another note, my mind immediately went to this country—the United States currently. Is the America you reveal in Thy Kingdom Come the America that the Democrats missed, somehow overlooked?

Richards: I think it’s the America that many people want to miss. Just think about Kathryn, the woman who is extremely overweight. You can just see people shaking their heads at her appearance. And she suffered unspeakably when boys she trusted raped her. She is rarely seen for who she is, but she is a spectacular woman.

Heritage Villa Nursing Home from Thy Kingdom Come, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Harris: It must have been profoundly complex for Javier to move between these real experiences he was having with you, and then go back to being in his To the Wonder role.

Richards: He had some trying emotional reactions during the process, as did Janine, as did I, as did everyone involved. It was made worse by the fact that Annie, the woman in the nursing home who spoke so beautifully to Javier, died the next day. She fell over and banged her head. It devastated him.

And Callie, the young woman with cancer—her visible suffering was almost unbearable. We questioned filming her, but she told us she was doing this for her kid. She said, “I want him to know that I really love him, because I’m not going to be around for much longer. This is a way for me to tell him that will last forever.”

Other things happened . . . We returned to the nursing home. We’re in there and this elderly woman, Lavonne, says to me, “What are you doing, dear?” I said, “We have a film going on about a priest coming in, and what he would do in the nursing home.” She says, “What will he be doing?” I say, “Well, he will be visiting patients, he may say the last rites.” She says, “Well, he can do the last rites on me.” So we said okay, and she closed her eyes and lay perfectly still. Javier went ahead, reading from the prayer book, trying to recite the last rites, and I did film, but clumsily. I felt terribly uncomfortable, envisioning this dear woman passing away. But I did the best I could, and got a little scene of him walking out of her room.

We were getting so involved in people’s lives; we were going really deep. But then we went to the county jail in Pawhuska, Oklahoma. I wasn’t sure whether Javier could take another episode. He was getting very emotional. I think we all realized that this could go on forever . . . And maybe we wanted to keep hearing people’s stories.

Osage County Jail from Thy Kingdom Come, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Harris: What happened when you went to the jail?

Richards: I met these guys and they say, “What would you like us to do?” I said to them, “Do what you want, but don’t go too heavy on him.” They understood. These are inmates. At the onset of our time together, one of them—Melvin K.—created this murderous character, but it didn’t go very far; Javier saw right through it.

Javier had such class because this guy kept blowing his cigarette smoke directly in Javier’s face, and he just rolled with the punches. At the same time, those cigarettes, the smoke, were gifts to a guy with a camera.

Harris: Yes, visually, that smoke, along with the blinding sunlight coming through the window, flanked by the two of them silhouetted, mostly in profile, is dazzling, and you never could have anticipated that.

Richards: But that’s how this whole experiential film happened. You begin in one place, not moving, not intruding, and things happen. The children look on, the daughter plays the guitar, tears come, a sexual assault is revealed, a butterfly truly does pass overhead.

There is this one scene of Javier with Callie. It is personally revealing of Javier, perhaps more than anything else in the film. When Callie walks away, out of view, he is left sitting there on the bed alone. He was a bit upset. It would have perhaps been kinder if I had not continued to focus on him, but, as with most every moment that I filmed, I let it play out.

Melissa Harris is coeditor of Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the present.

Thy Kingdom Come will have its world premiere at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Film Festival in Austin, Texas, on March 10 at 11:30 a.m. There will be additional screenings on Tuesday, March 13 at 6 p.m., and Friday, March 16 at 12 p.m.