Photographing Tupac, Biggie, and Everything in Between

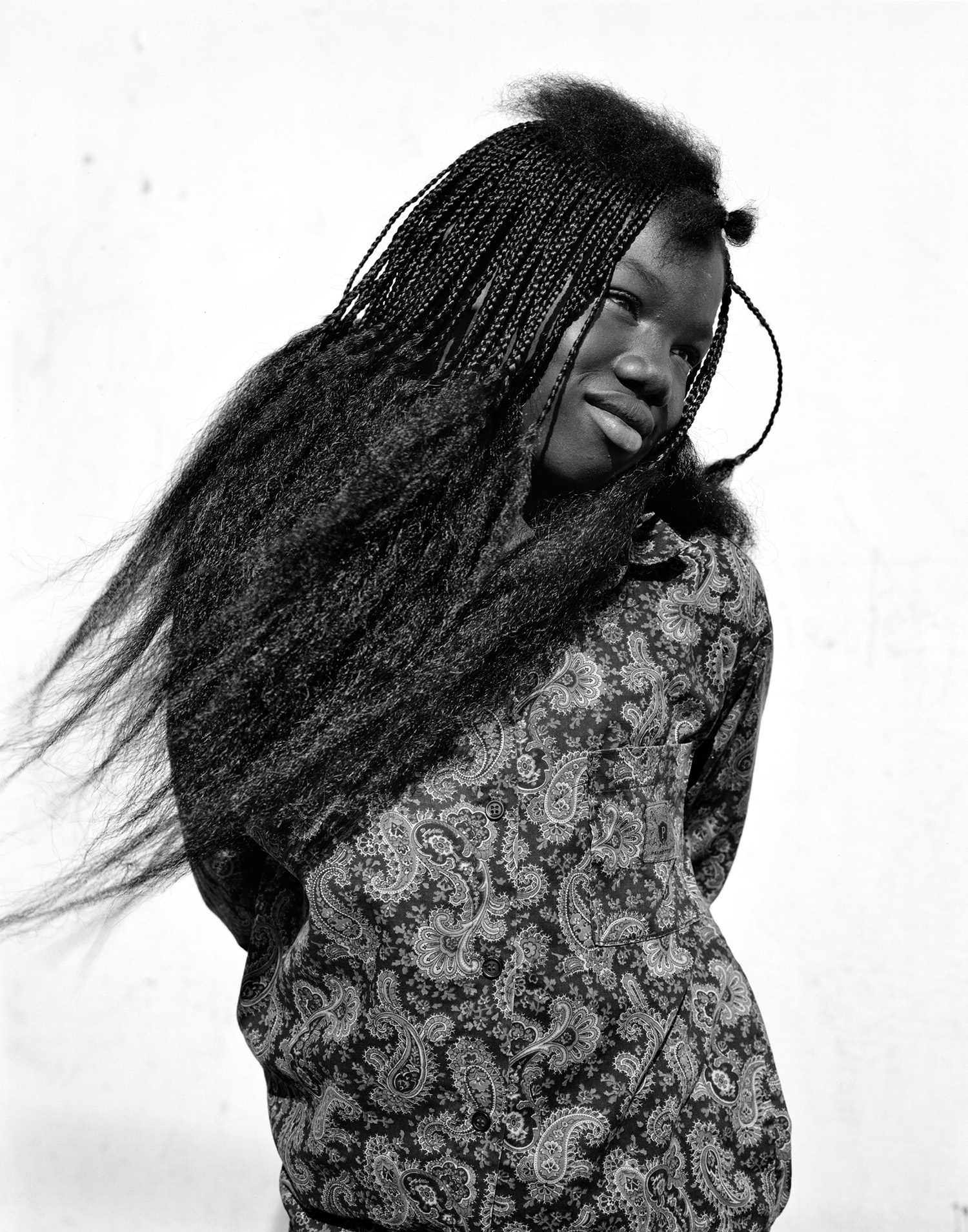

Dana Lixenberg, Wilteysha, 1993, from Imperial Courts 1993–2015 (Roma Publications, 2015)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

During the past two decades, Dana Lixenberg has produced an extraordinary collection of portraits of individuals and communities. Whether facing celebrities for editorial shoots or engaging with ordinary citizens, Lixenberg’s lens reflects her subjects with consistently measured sensibility. Throughout a range of subjects and social situations, Lixenberg maintains what late artist, educator, and photo editor George Pitts described as her “unvarnished” photographic style. To date, she has published eight books of photographs, a few of which have considered the culture and place of Lixenberg’s native country, the Netherlands, while the majority of the published material has focused on the United States. Much of this work originates as editorial assignments; and subsequently develops into long-term projects.

In each, Lixenberg’s commitment to her subjects results in an archive where the cultural meanings and narratives of the images continually expand. “I’m trying to make an image that really can tell a story and you can spend time with. An image that can live beyond the context of what it was shot for,” Lixenberg explains in her most recent publication, Tupac Biggie (Roma Publications and Patta, 2018).

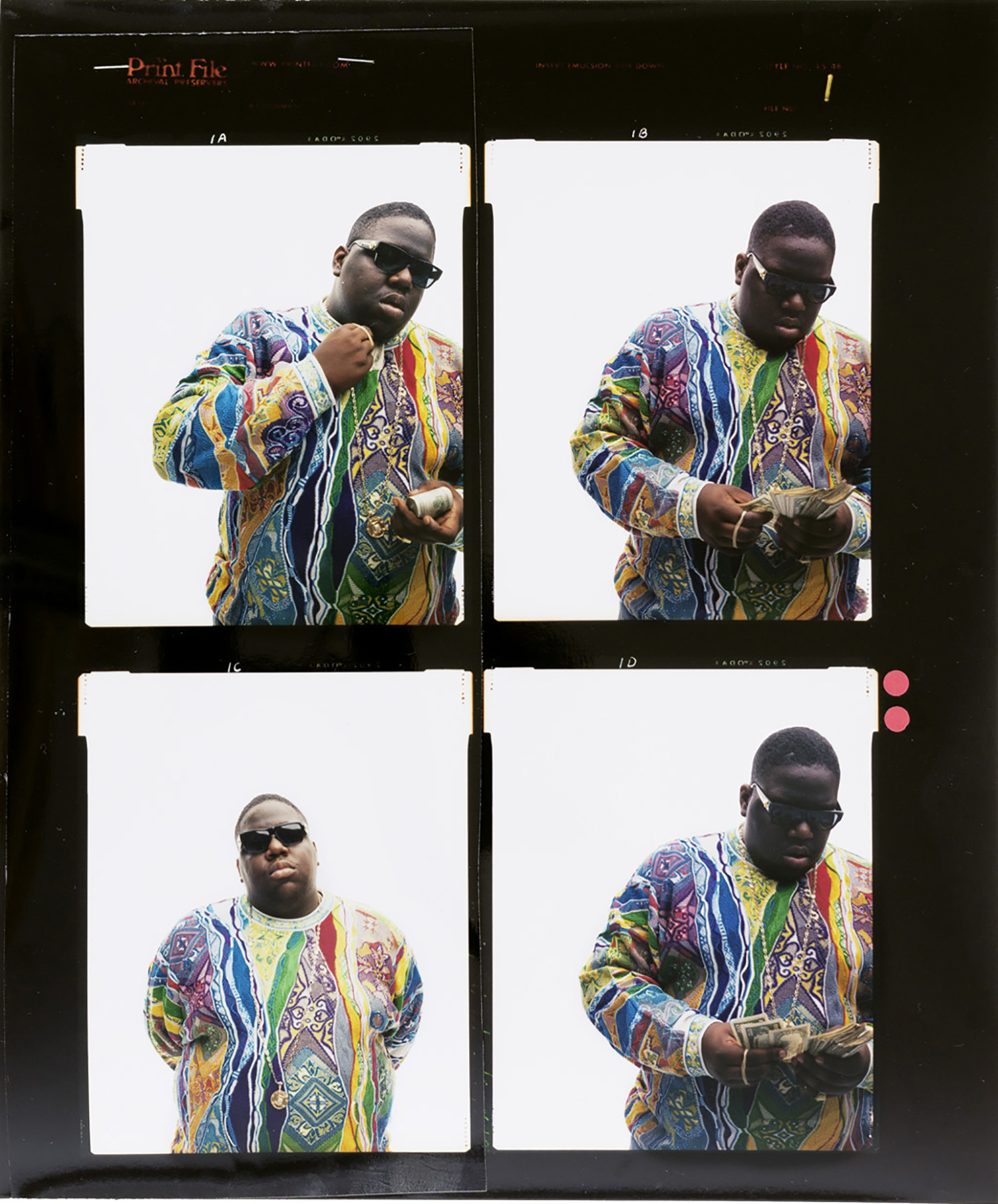

Dana Lixenberg, Contact sheets from photoshoot for VIBE, Christopher Wallace (Biggie), New York, NY, 1996, from Tupac Biggie (Roma Publications and Patta, 2018)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

In Tupac Biggie, Lixenberg revisits her photographs of the two pop-culture icons—made for Vibe in 1993 and 1996, during the early years of the influential hip-hop culture magazine. Signaling the magazine as the original vehicle for the images, the book displays Lixenberg’s portraits of Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls (aka The Notorious B.I.G.) on glossy pages, saddle-stitched into an oversized format. A progression of Lixenberg’s archival images of the twenty-two-year-old Tupac Shakur runs from the front of the book to the center—beginning with a facsimile of a black-and-white, 4-by-5-inch negative image, and followed by multiple pages of contact sheets from the shoot, an enlarged gelatin-silver print, and tear sheets of the original and subsequent issues of Vibe in which it appeared. In the well-known image, the two knot-ends of

Dana Lixenberg, Contact sheets from photoshoot for VIBE, Tupac Shakur, Atlanta, GA, 1993, from Tupac Biggie (Roma Publications and Patta, 2018)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

Tupac’s front-tied bandanna descend down both sides of his face, accentuating his poised look. Small droplets of rain fleck his denim shirt, worn open and displaying his diamond-adorned crucifix. A parallel succession of archival images of Biggie expands from the back of the book toward the center. Lixenberg depicts Biggie in a range of poses: most often defiantly staring down the camera, at times appearing beside producer Sean “Puffy” Combs (currently known as “Diddy”), and—in one of the most memorable images—wearing a flamboyant Coogi sweater and shuffling a large stack of money. The division between Biggie’s right side of the book and Tupac’s left side recalls the East Coast vs. West Coast rivalry perpetuated by the performers, their crews, and the media at the time, while an essay by Vibe editor Rob Kenner recollects the prominence of the hip-hop magazine, as well as its complicity in fanning the flames of the feud between Tupac and Biggie before their fatal shootings, in 1996 and 1997, respectively. The book is dedicated to George Pitts, Lixenberg’s photo director at Vibe, who died in 2017.

Dana Lixenberg, Lisa Kudrow, Los Angeles, CA, 1999, from united states (Artimo, 2001)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

Lixenberg’s ability to create subtly provocative portraits of public figures led to frequent editorial assignments for a variety of magazines, including Interview, Rolling Stone, Details, Elle, Esquire, Out, and many others, in addition to Vibe. united states (Artimo, 2001), a compilation of approximately eighty photographs Lixenberg made on assignment from 1994 to 2000, forms an unexpected, collective portrait of American culture. The book interrelates recognizable cultural figures with noncelebrities, photographed because of particular social circumstances they represented or were associated with—for instance sex work, college sororities, illness, incarceration, and homelessness. In the book’s afterword, George Pitts elucidates, “Virtually all celebrities portrayed by Lixenberg are rendered in a vulnerable way, and perhaps that’s why these images warrant repeated viewings . . . Lixenberg extracts their ordinary (yet richly human) qualities . . . It is almost the reverse of what she does with noncelebrities. With them, Lixenberg reveals their charisma.”

Dana Lixenberg, Snoop, 1993, from Imperial Courts 1993–2015 (Roma Publications, 2015)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

The first Lixenberg photographs to appear in Vibe were not of celebrities, but rather portraits of residents of the Imperial Courts housing project in the Watts area of South Central Los Angeles—photographs that Lixenberg had shown to George Pitts. Remembering the context of the day, Pitts reflected on Lixenberg’s “tough non-pandering aesthetic,” in contradiction to “the slicker celebrity and fashion-oriented content,” which helped establish the visual tone of the magazine. Lixenberg continued to photograph the community there for twenty-two years, ultimately producing Imperial Courts 1993–2015 (Roma Publications, 2015), an extensive volume depicting generations of residents photographed on the grounds of the urban housing complex.

Dana Lixenberg, David A. Taylor, 2000, from Jeffersonville, Indiana (Artimo, 2005)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

Lixenberg had first traveled to South Central to photograph the aftermath of the 1992 Los Angeles riots on assignment for a Dutch weekly, Vrij Nederland. Witnessing the extent of the damage in the city moved Lixenberg to return to the area and establish ties with the community, which lead her to Imperial Courts. Around the same time, Lixenberg embarked on another long-term project— photographing the homeless population in Jeffersonville, Indiana. While a handful of the people photographed in Jeffersonville appear in united states, Lixenberg’s collective portrait of a fragmented community culminates in her subsequent book Jeffersonville, Indiana (Artimo, 2005). The work originated as an assignment to photograph homeless women for Jane, yet it grew into a more extensive undertaking over the course of seven years, from 1997 to 2004. In both Imperial Courts and Jeffersonville, Indiana, Lixenberg approaches complex social realities with an austereness whereby she distills the human subject amid a reductive palette of visual signifiers. The accumulation of time past, and an emphasis on the shared presence of the photographer and subject, activate the singular frames beyond stasis toward a more elastic corpus of images, social exchanges, and meanings.

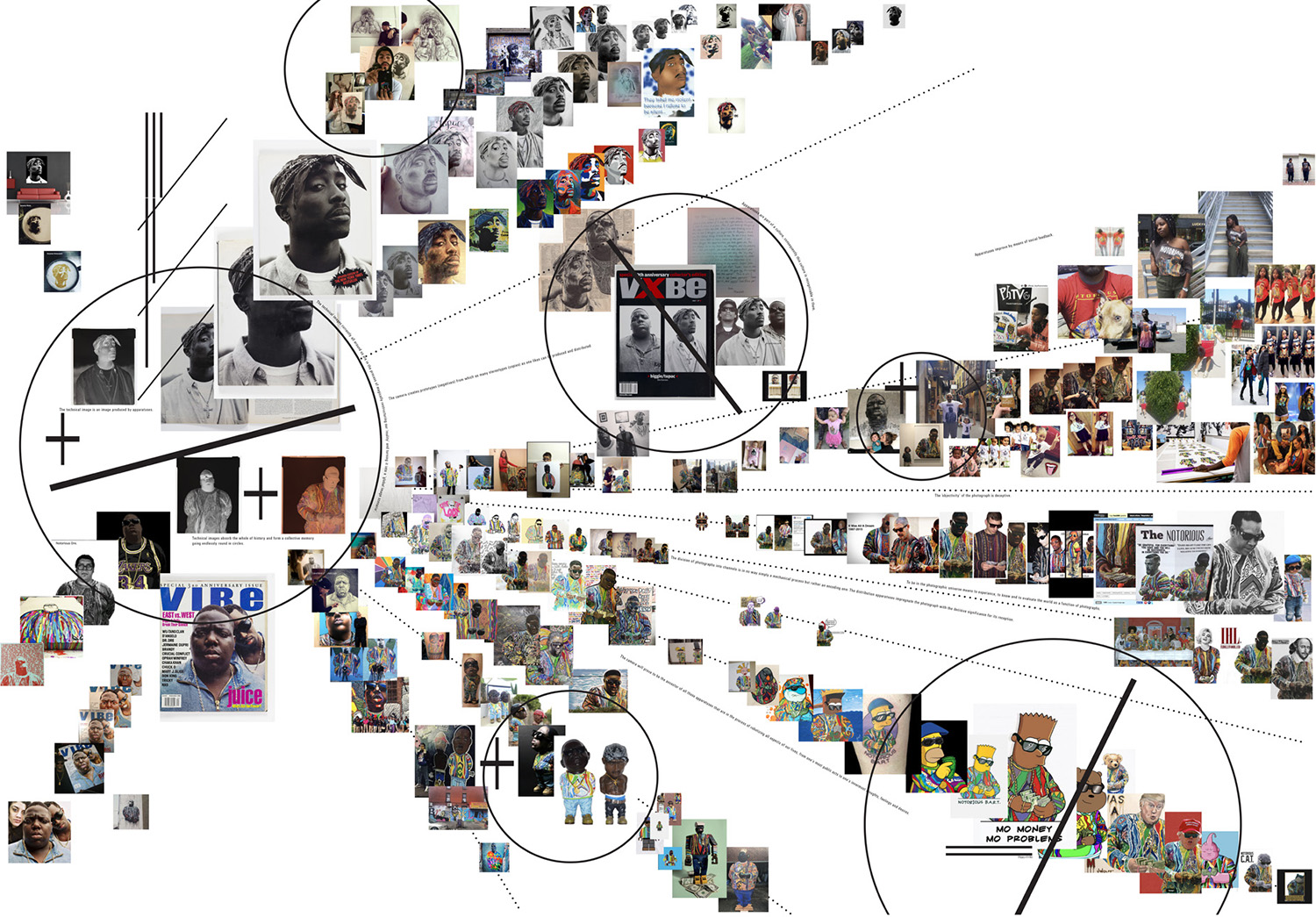

Centerfold poster from Tupac Biggie (Roma Publications and Patta, 2018), design by Linda van Deursen

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

Lixenberg’s reexamination of her photographic archive for Tupac Biggie remembers history through the documentary temperament of its images. At the same time, the volume furnishes a mirror in which to glimpse a contemporary image culture in which the proliferation of images and their meanings stretch the imagination. Lixenberg’s material works, commissioned and distributed by Vibe, play out on the pages of the compendium as traces of their subjects (and simultaneously register the images’ usage by Vibe). Nestled within the book’s center, a giant foldout poster shifts the character of the work considerably. On the poster’s verso reads an explosive, free-form poem remembering “Tupac and Biggie,” by writer and activist Kevin Powell. On the front of the poster appears a graphic representation of the trajectory of Lixenberg’s images through their appropriation by a global mass image culture that has refashioned them during the last two decades into memes, taking such forms as murals, paintings, tattoos, and merchandise, such as T-shirts and figurines. Lixenberg’s gesture to include within Tupac Biggie the collectively constructed copies that succeed her original images acknowledges a greater conception of her photographic practice through the medium’s ever evolving social reception. At once, Lixenberg’s work fills the space of the photobook, the magazine, and appropriation by the public. Lixenberg continues to expand the possibilities of photography through a persistent and elongated practice across genres, in which a multiplicity of readings, including mourning and—at the same time—a playful examination of the image, are each evident.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review, Issue 017, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

American Images is on view at GRIMM, New York, through February 29, 2020.