A Love Song for New Orleans

Drawing inspiration from Walker Evans, Stephen Hilger photographed a city’s disappearing neighborhood.

Stephen Hilger, Bar, 2011, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Now she’s gone and left me

I’m worried as can be

Oh I’ve searched this world all over

Wonderin’ where she could be

I would ask that she forgive me

And maybe she’ll come back to me

—Louis Armstrong, “Back O’ Town Blues,” 1946

Stephen Hilger’s book Back of Town (2016) begins with an epigraph quoted from the lyrics of Louis Armstrong’s mournful song about the loss of a lover. The photographs that follow depict part of a neighborhood of New Orleans that Hilger came to know as the Back of Town, a historic district devastated during Hurricane Katrina, partially rebuilt then marked for demolition, which he recorded during his time as a professor at Tulane University. Called Lower Mid-City by newspapers and preservationists, the approximately twenty-five blocks these pictures span were razed in 2012 to make room for new hospital buildings. I recently spoke with Hilger about photographing this place as it disappeared, and about how he made the pictures into a book.

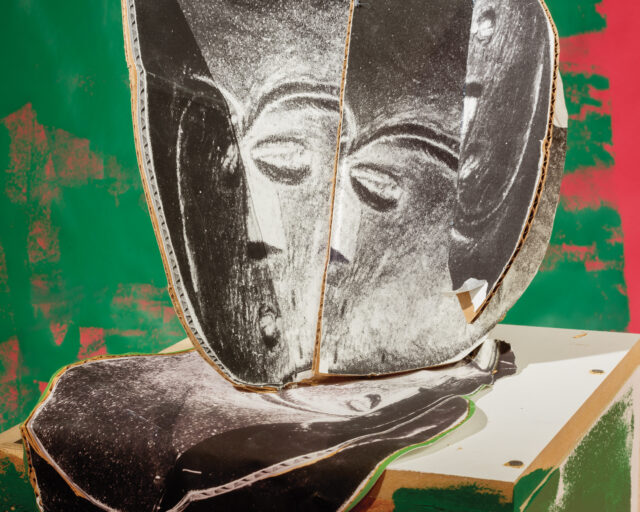

Stephen Hilger, Monument, 2011, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Matthew Leifheit: How did this book project begin?

Stephen Hilger: I want to tell you about how I ended up in the Lower Mid-City or in the Back of Town or in this particular neighborhood in New Orleans photographing. But, before that, I’ll just say, I was there and it was very sleepy. There was not a lot of activity, and over the course of four years that I photographed there, there was less and less life. But there was always something, which is part of what kept me coming back. I was at a bar, not necessarily to drink but because it was one of the places on the block that had some life, some people. The bar was called the Outer Banks, and I was photographing the people in the front of the bar, and a man confronted me and said: “What the fuck are you doing?” I tried to explain it to him, but he wasn’t really listening to me, so I went and bought a beer and before long he was back, and I bought him a beer and we talked. I got to know him, and photographed him. Our relationship was based on access he could provide me to his world and access that I could provide him to my world. Our conversation was through the photographs. I feel like he was the sentinel of the neighborhood. He was also a hustler. His name was Brian. He knew the comings and goings of the place and was concerned for me and my safety.

Leifheit: Concerned about your safety or concerned about the way you might be depicting things?

Hilger: Well, he was initially concerned with why I was there, and I explained it to him. I told him that I heard that the neighborhood was disappearing, that it was being torn down, and that I was interested in writing it down—getting to know it and trying to understand it through pictures. There’s a big insider/outsider dichotomy that runs through a lot of things in New Orleans, including photography. I felt it in New Orleans quite a bit in my daily life: You were from New Orleans or you weren’t.

Stephen Hilger, Traveler, 2010, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: You’re from Los Angeles, and you live in Brooklyn. So, why were you in New Orleans?

Hilger: I was teaching at Tulane. The four years I was there, from 2008 to 2012, were the four years I was photographing in this neighborhood. My main activity as an artist during those years was photographing this particular place.

There are a few reasons I wanted to mention Brian. I wanted to photograph the place very completely—in a lot of different ways. The most accessible thing was the street and the exterior of buildings, but then I wanted to go inside and photograph the inhabitants or the drifters passing by. When I was photographing this dying neighborhood, there weren’t really permanent residents—it had reached a terminal stage where people were mostly moving through and squatting. So, I took portraits, photographing Brian on a number of occasions. I met a few other people through him and people saw me through him and it was part of my entree into the place. But Brian’s not in the book, and there’s another half dozen portraits that aren’t in the book. The book is really about the distance that occurs. The more that I’m there, the more that I’m observing, the less that’s there, the farther away things are. It’s not about the particular voices of these people. It’s not even about their particular experiences. But it is about the experience of being in the place more broadly. One thing my friend and mentor, Thomas Roma, said about the work was that it reminded him of veins and arteries and a movement through these vessels. I’ll take that further and say that this is the biology of a sick person, that things are slowing down and things are becoming attenuated.

Brian’s not in it, and I’m talking about that because I think, on some level, I feel that Brian is missing. At the same time, I think that the work is complete. I think it’s OK to feel that missing someone or something, which is really apt for New Orleans, because it’s about a chunk of something being torn away—purposefully forgotten and purposefully erased.

Stephen Hilger, Footprint, 2012, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: In this aerial view, a large piece of land looks like it has been scraped clean. There are faint squares where I imagine buildings must have been. This is where the neighborhood was?

Hilger: Yes, that’s the footprint of the planned demolition, and that is actually one of two adjacent footprints of spaces that were systematically dismantled in order to build new hospitals. What drew me to the place was Charity Hospital, which was one of the oldest public hospitals in the country. It has an infamous place in history because of Hurricane Katrina. Patients were cut off. It was a horrific situation. I was drawn to the building itself. It was a monolithic concrete structure that was very imposing, empty, and there was nothing happening there. I’ve been interested in things that are disappearing, and I often look at architecture, and while I was looking at those things and in neighborhoods that were adjacent to the back of town, I read a New York Times article about Lower Mid-City. Two hundred houses and however many acres having rebuilt itself after Katrina, only to be marked for demolition and subject to what is called “expropriation.” It sounds a little more brutal than eminent domain. One of the ironies about the Back of Town, though, is that it was rebuilt only to be torn down.

Leifheit: To make room for new hospitals?

Hilger: Yes, which was a great thing, but at the expense of people living there. And then there was a hospital that stood empty. There are impulses to think about how photography might serve some purpose to saving the residents’ homes, and I befriended preservationists and other people who were rallying for this. But, ultimately, I realized the place was doomed and damned and there was nothing I could do about it but describe it.

Stephen Hilger, Niche, 2010, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: Although sometimes it’s essential if communities document their own spaces and lives, in this case it seems equally important that an outsider came in to do this work. And the distance you have as an outsider in this situation is actually beneficial in some ways.

Hilger: The community there was delicate; it was just hanging on by a thread. It was shifting. There were people who were a part of the residential community of the place, and then there were people who were part of new immigrating communities moving in. I observed a migrant laborer Latino community who moved in temporarily, who I think were possibly unaware of what lay around the corner. So, there were a lot of different communities present, even in a place that was dwindling and becoming smaller and smaller. Through the photography, and being there, you think about these things and are interested in them. Some of it is evident in the pictures and some of it is not, because the aspect of community is not what drove the project. One can imagine it as a once vibrant, working-class community, and I think that’s part of why I wanted to depict the place, but depicting it at a time that was very specific to the end.

Leifheit: The reason I ask was because I was thinking about a previous project you did documenting LA’s Ambassador Hotel before its demolition, which included an online repository for other peoples’ documentation of the place. I wonder what kind of image culture would exist in this place already that’s made by residents now or in the past.

Hilger: That’s an interesting question. I’d love to see some pictures of the place and the community. I’m sure they’re out there but they might be scarce because of the historical situation and the exodus from the place. You can imagine this place emptying out as urban places do, and then, obviously, the hurricane, followed by the expropriation, put the nail in the coffin.

Stephen Hilger, Waiting, 2011, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: When they are brought together in a book, does something change about the pictures?

Hilger: The book allows the pictures to become a narrative.

Leifheit: I also think it gives it more of a connection to literature.

Hilger: Right, and if it could be a book of literature, it could also read like a history book, a historical document. I am interested in history, and our memory of history. Books are still a huge part of that. It’s a mass form, even a photography book that is a smaller edition. It ends up in a number of people’s hands, in libraries, in other writers and photographers’ hands. It becomes part of our memory of a place. We can locate New Orleans in some of the pleasures and glories of the place like the Saints and Mardi Gras, the music, the food. I don’t take these things lightly at all; I think they’re incredible, unique parcels of American culture. But there’s also sadness and a loss and a crime that’s been committed in New Orleans over and over again. I think that my work is more about that than the glories of the place. It’s about beauty, but it’s about something that’s lost and people who weren’t on the winning side.

Leifheit: It seems like for you there’s more urgency in depicting this than the joy of it. It seems like there’s a utility to this in the same way.

Hilger: It’s interesting what you said before about this particular place, and I wonder what would the pictures of this place look like if they were made by the members of the community. I think there might not be so many pictures of this place from this period because the permanent community was mostly gone. But I wanted to show what the place looked like during that period.

Stephen Hilger, Electronics, 2010, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: Are your photographs also documents?

Hilger: I like to think that my work in cities is useful historically. But there’s that reading and there’s also the notion of the lyric documentary.

Leifheit: Some kind of poetic truth?

Hilger: I’m not sure about the truth. I don’t think of documentary photography as being about truth, but rather viewing and experiencing the world. I mean, lyric documentary in the way that Walker Evans described a certain type of photography that was made from hard-boiled facts but also songlike.

Leifheit: What kind of song?

Hilger: It’s kind of a love song. It’s about being left behind, that sort of love song. It’s about that feeling that you lost someone.

Back of Town: Photographs by Stephen Hilger was published by SPQR Editions in 2016.