Love Visual: A Conversation with Haile Gerima

Visionary director Haile Gerima emigrated from Ethiopia to the United States in the late 1960s. Exploring African and African American narratives, his works, sometimes born of dreams and visions, have inspired a new generation of filmmakers.

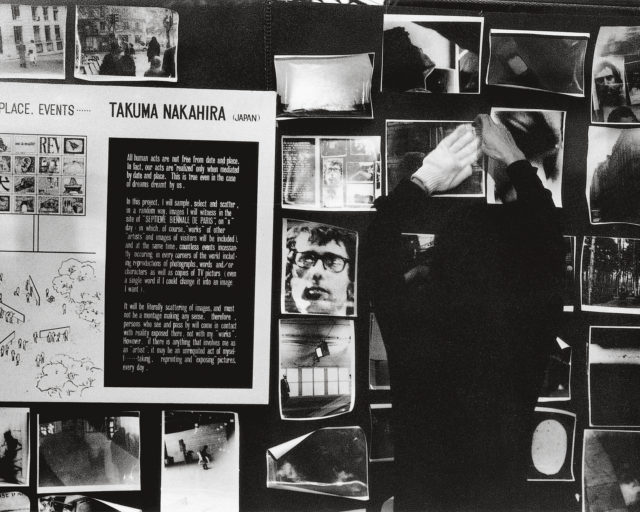

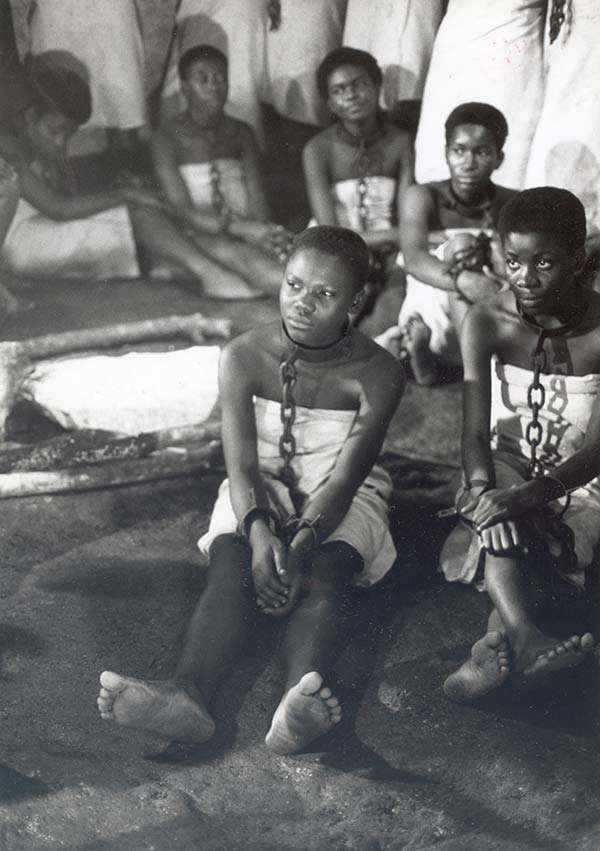

Haile Gerima, Still from Sankofa, 1993. Courtesy the artist

Dagmawi Woubshet: I think it’s a fair statement to say that one can think of Haile Gerima’s work as a meditation on love. I am reminded of James Baldwin in The Fire Next Time, who says that “love takes off the masks we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” I think your films, Haile, actually allow us those kinds of self-revelations. And so I hope we can glean from the questions that we’ve come up with, the different idioms of love, and the different inflections of love that show up in your body of work.

Sarah Lewis: Thank you, Dagmawi. I wonder, Haile, if you would speak to us a bit about the courage it took to begin your journey from Ethiopia to Chicago, studying theater in the 1960s, to Los Angeles studying film to tell stories that have moved us all?

Haile Gerima: First, I just want to thank you both because it didn’t really occur to me to … I’m so alienated about the whole idea of love. I’m not sure I deserve such an honor because of the few films I have done in the world. I didn’t have the resources to have done more. Sankofa (1993), I should have done at least ten sequels because I have fifteen scripts. And so, in a world where one is denied the tools and resources, in that kind of dire state of struggle to gain my right to tell a story, to think of such very insightful emotional dynamics in my work is really a blessing. Now for me, I am a human being who’s been lied to. So when I shoot, it’s, for me, a rifle, it’s a gun, it’s an explosion. Every film is a staircase to respond to my interest to cleanse my own state of occupation. It’s kind of a decolonizing journey, and no one is going to finance me, no one is going to say, “Here’s money to tell another story.” Unless she drives Miss Daisy I have no chance of being financed by the present arrangement.

Woubshet: We wanted to ask you, since you are really the product of two civilizations—an Ethiopian civilization and also an African-American civilization—if you could talk about the insight that each has given you about love, and also the resources that each civilization has given you in becoming the kind of filmmaker you are.

Haile Gerima, Still from Ashes and Embers, 1982. Courtesy the artist

Gerima: Well, let me put love aside for a second because I’m the least developed person to discuss love. But let me speak about these two situations that I find myself in. I think, for example, World War II began in Ethiopia. Ethiopia was the first country where Mussolini waged war and Ethiopians were the first casualties of poison gas. Their history is still not told. Why? Because we are in this Eurocentric educational university, global university, where our instincts and tendencies are managed and conducted by this higher empire, which is the United States empire. I am the product, the grotesque and disciplined product, of the American empire. This is how I think we have to look at my work, that the American empire was where Haile Selassie ran because of the trickster British colonial idea of colonizing Ethiopia. To prevent that, he went into the bosom of Roosevelt, and Ethiopia, unlike its past history, became in the orbit of the American empire. And so our educational systems were changed. Twenty-one-, eighteen-year-old American Peace Corps came to teach us. Local Ethiopian educational system was completely obliterated, which also obliterated my father, who wrote plays and never knew Shakespeare nor Molière. His plays were displaced and my immediate inheritance to be a storyteller in Ethiopia was completely destabilized.

And so everything I do is to reconnect my disconnected umbilical cord. My focus is completely resistance, and love in that whole metrics is really the fact that we dare to still love. It amazes me. I’m not yet developed. I’m not going to claim my films do that. I just want to hear you guys tell me it does a little bit here and there. But the point is … and the African-American now comes in here. I came to America and I was, in response to my conditioning … The first demonized population in Chicago I tried to run away from were African-Americans. But by the time of the Black Power Movement, 1968–69, I had the biggest afro of any African-American. I am an Ethiopian citizen. I don’t intend to be an American citizen, but I have a big, big … owe to African- Americans for awakening me to want to find out who the hell I was, and that is not a simple debt.

Haile Gerima, Still from Sankofa, 1993. Courtesy the artist

Woubshet: One has to prepare in advance to watch your films because they are emotionally very heavy. It’s not Friday night at the movies, you know. Even though the characters achieve some form of self-revelation or self-consciousness toward the end of your films, they go through immense amounts of pain and suffering. They’re deeply haunted characters, and it seems, in fact, a signature of yours is to thrust their interior, psychological turmoil on the screen for us. And you are relentless about that. Can you talk about how your deeply troubled characters ultimately gain some form of self-possession?

Gerima: Well, that’s very nice, and thank you. I’m going to tell you there are two things in motion. First, in general, just even the idea of storytelling—the aesthetics, the accent, and the structure of storytelling still has to operate in the empire of this Eurocentric America. America is really European aesthetics. In general, the vocabulary of America is a white supremacist vocabulary and Europe lives in America with all of us being the ambassador and emissary of its vocabulary. My struggle is not only what I want to tell, but it is the very form of storytelling that I am in constant struggle with. Am I succeeding? No, it’s an imperfect struggle that is on a journey of someday finding this stable, coherent, narrative gratification. And so, the intensity that I think you are talking about comes from the fact that I am in a struggle. That is part of it.

Black people that I know are struggling every day. In struggle there is intensity and resistance, and there is also love in that intensity. To dare to love within the circumstance of an intense struggle is an amazing situation. I cannot claim I have succeeded to do that. I don’t know if I answered you, but I improvised my way through.

Lewis: The idea of love as connected to a right to have agency about your future seems to be a through line in your films; a right to live out your potential. We see this in Sankofa, in Bush Mama, (1979). Can you speak to us more about this focus on right to the future as a motivator?

Gerima: Well, you know, I think … Frantz Fanon’s idea that every generation has a responsibility some fulfill and some betray. Out of that I decided that some of us come on this earth to be fertilizers. I live amongst fertilizers knowing there will be firebrand children that will not have the same entrapments that postpone them from grabbing their historical making process.

Haile Gerima, Still from Sankofa, 1993. Courtesy the artist

Lewis: We wanted to also speak about the segments and codas you create by having the sounds of everyday activities, specifically in Harvest: 3,000 Years (1976) and Ashes and Embers (1982), whether it’s cattle sounds in the harvest or the creaking of the swing with the grandmother at the end of Ashes and Embers as she is telling her story to Liza. We wondered if you could just tell us more about how the stories and their environments have inspired your journey to filmmaking.

Gerima: When I came to Chicago and finally UCLA, I had two choices: to reconnect with something that has been very insistent in my life; to reconnect to the melodies and the storytelling. I have students who are always plugged by earphones, furthering their own mental conditioning, and could not build sound tracks when they do their films.

The crackling fire is the sound track of my grandmother, which I did in Ashes and Embers. Ashes and Embers, for example, is built on the whole crisis I was having. When does a generation listen to the passing generation? I was working on this thing jazz musicians call the ripe moment. When is one ripe to hear the truth?

I think all my other films did benefit a lot because even structurally I wanted to abide by the idea of when does one see the light. What kind of generational struggle takes place for that generational transaction? Is it when you want it or when the kid is ripe, and is the kid ripe now or one hundred years later? That is what I learned.

Woubshet: Following up on that, your films have such a clear political content to them, but then you get these long interludes of everyday life, the quotidian.

Lewis: There is an ethic of care you have created, a legacy at Howard University and in Washington, D.C. You have been there for thirty years now and with your students, you teach them with a level of love that is so profound to hear.

Gerima: I think black people carry a genomic story in their body in this country. If they don’t want me to help them activate it then I’m useless because I am not a teacher that is there for salary. I declined many film school offers in Europe to go to Howard because I was looking to teach black kids who I felt didn’t have to go, like me, to UCLA to spend more time justifying their story is normal instead of the technical discussion in white schools. I went to a school where I want to have black kids like me who are really in urgent situation to tell the story of their grandmother or their grandfather. I said, “I want to be a part of a school like that.”

This article is adapted from “Love Visual: A Conversation with Haile Gerima,” originally published in Callaloo, vol. 36, no. 3, Summer 2013, and reprinted courtesy of Johns Hopkins University Press.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.