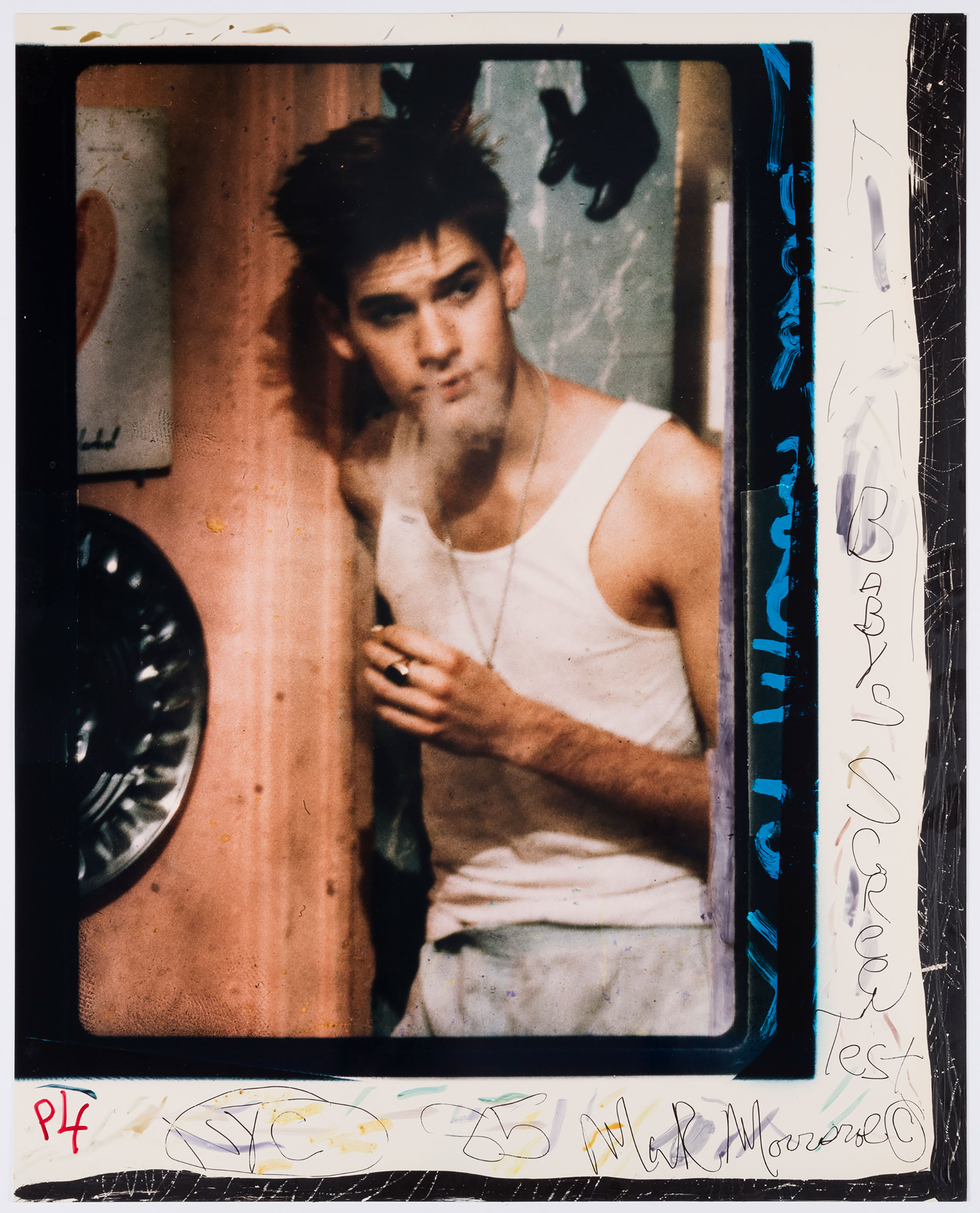

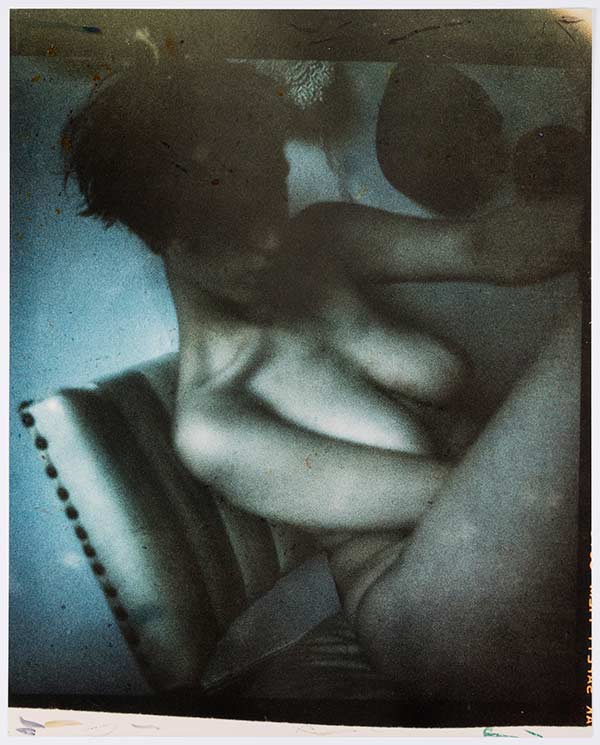

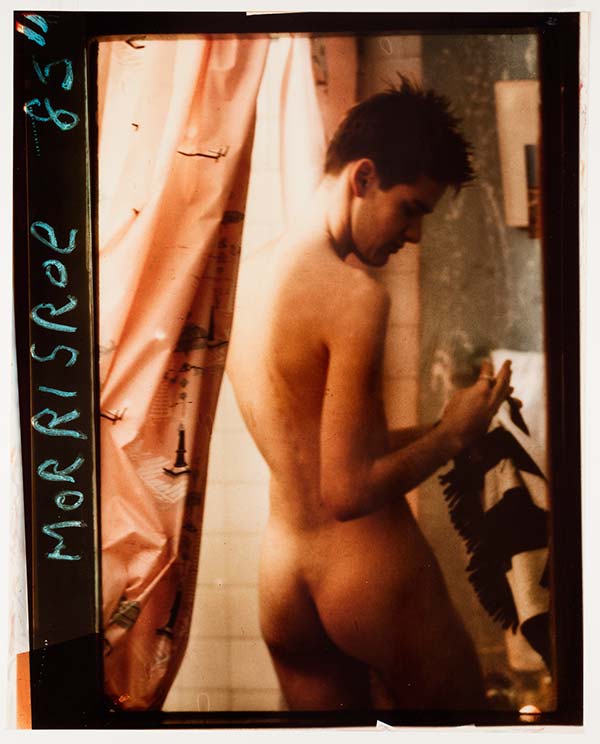

Mark Morrisroe, Baby Steffenelli (John S.), 1985

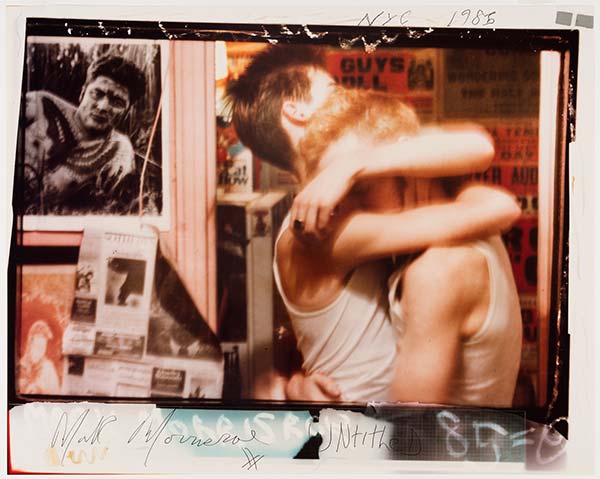

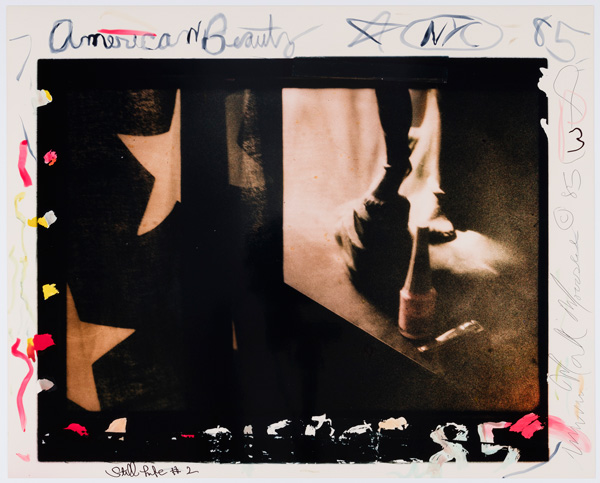

At the end of the stairway to the lower galleries of Alexander and Bonin’s new location in Manhattan’s financial district, there is a grainy color image of two men frozen in ecstatic embrace. Titled Untitled (John S. and Jonathan), the C-print, made in 1985 from sandwiched negatives, has some kind of life about it—an electric draw produced by its nubile highlights and off-kilter framing. The image is by Mark Morrisroe, who died in 1989 at the age of thirty, and it’s printed with a wide border, enshrined in frenetic pen marks, scratched emulsion, out-of-focus confetti in darkroom colors, traces of multiple negatives, and otherwise fanciful processing. Stashed in the attic of a private home in Boston for over thirty years, these unique works are now on view to the public for the first time.

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

The taller of the two figures in Untitled (John S. and Jonathan) is John Steffenelli, a subject with teen heartthrob allure who appears in three of the eight pictures on view in Mark Morrisroe: Works from 1982–85. The red-haired boy on the right is distinguishable as the artist Jack Pierson, former boyfriend and frequent muse of Morrisroe’s. “It was my first intense gay relationship,” Pierson told me recently. “It was two years solid of living together and then I moved to New York to get away from him. I mean we were both drug addicts and alcoholics. But he was, as far as I’m concerned, much worse than me. So it was kind of lunacy to be around him.”

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

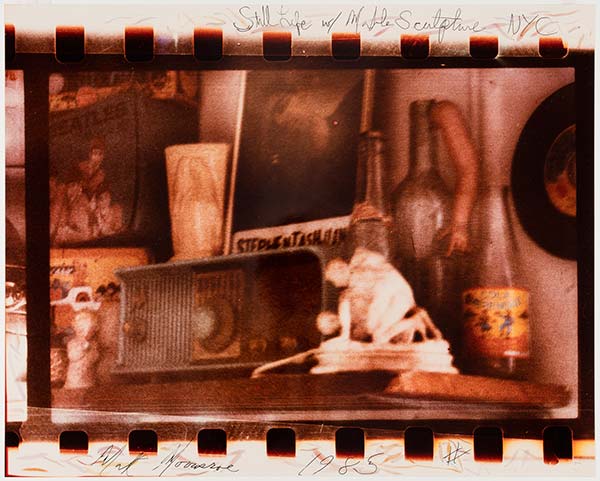

A climate of lunacy is apparent throughout much of Morrisroe’s work, particularly in his so-called “sandwich prints.” Figures dissolve into shadow and film grain, encircled in multilayered jabs of neon marker scrawling stars, symbols, dates, and locations, creating a dream world that is alive with sex and freedom. Standing amid such colors provides a glimpse into a more bohemian time, when artists in downtown New York were redefining the expressive possibilities of identity and gender in art making. (Always preferring the margins, Morrisroe himself moved from Boston to Jersey City.)

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

These pictures also reanimate a brief, seemingly hedonistic era in advance of the AIDS crisis, which felled a generation of artists, including Morrisroe. Despite his short career, Morrisroe managed to leave behind more than six hundred color photographs and thousands of Polaroids, an archive replete with a sense of urgency, a sense that time was running out. Yet, for an artist of Morrisroe’s cult following, there are few opportunities to see work in depth. The only comprehensive Morrisroe retrospective in the U.S., presented in 2011 at Artists Space more than two decades after his death, was based on a 2010 survey mounted by the Fotomuseum Winterthur in Switzerland, where Morrisroe’s estate has been housed since being acquired by Collection Ringier in 2004. Because the vast majority of his work is held in Winterthur, only the few scattered pictures he sold or gifted during his lifetime tend to crop up in exhibitions. (Six additional sandwich prints are featured in Human Interest, the Whitney Museum’s installation of portraits from the collection.)

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

The works on display at Alexander and Bonin were consigned through a neighbor of Morrisroe’s in Boston. “What he told me is basically that when Mark needed money to pay the rent, his neighbor would buy a photo,” gallerist Ted Bonin said. “The funny thing is, he never framed them, they were never exhibited, they were kept in a folder in his attic along with some Nan Goldins.” Even though eight C-prints might not compare to a retrospective, this modest exhibition is a rare opportunity. Unlike its digital counterpart, analog photography has a clear path of indexicality, where the light that touched the subject was absorbed by the negative and reborn onto paper. Seeing the end stage of this intimate process in person makes the prints appear more alive. In fact, they carry a human trace of the past: as is so unusual in contemporary photography, the margins allow us to actually see the artist’s hand.

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

If you ask the gallery staff, there are more Morrisroe prints to be seen in the back room. Since the exhibition opened in October, collectors have approached Alexander and Bonin with an offering of smaller works by Morrisroe, discrete Polaroids and the gauzy gelatin-silver prints he made from them. Perhaps these new finds, when collected, will be the basis of more exhibitions to come..

Mark Morrisroe: Works from 1982–85 is on view at Alexander and Bonin, New York, through December 22, 2016.