Marking Time

When a loved one is incarcerated, how do portrait studios keep families together?

Nicole (the author), Allen, and Sharon (Allen’s mother), August 2012

Since 1994, I have had an exchange of words and images with my cousin Allen, who was sentenced to life in prison at the age of eighteen. We write to each other regularly, often reminiscing about growing up in southwest Ohio. There is such a familiarity in our connection, although our time together is limited to a couple of hours during each of my visits to see him. Allen and I grew up as siblings, along with several other first cousins in our large and close-knit family. His mother is my mother’s older sister, and child-rearing was very much a group effort that was shared among all the female relatives.

Allen ends all his letters to me in the same way: “Niki, send more pictures. Love, your lil cuz Allen.”

Courtesy Nicole R. Fleetwood

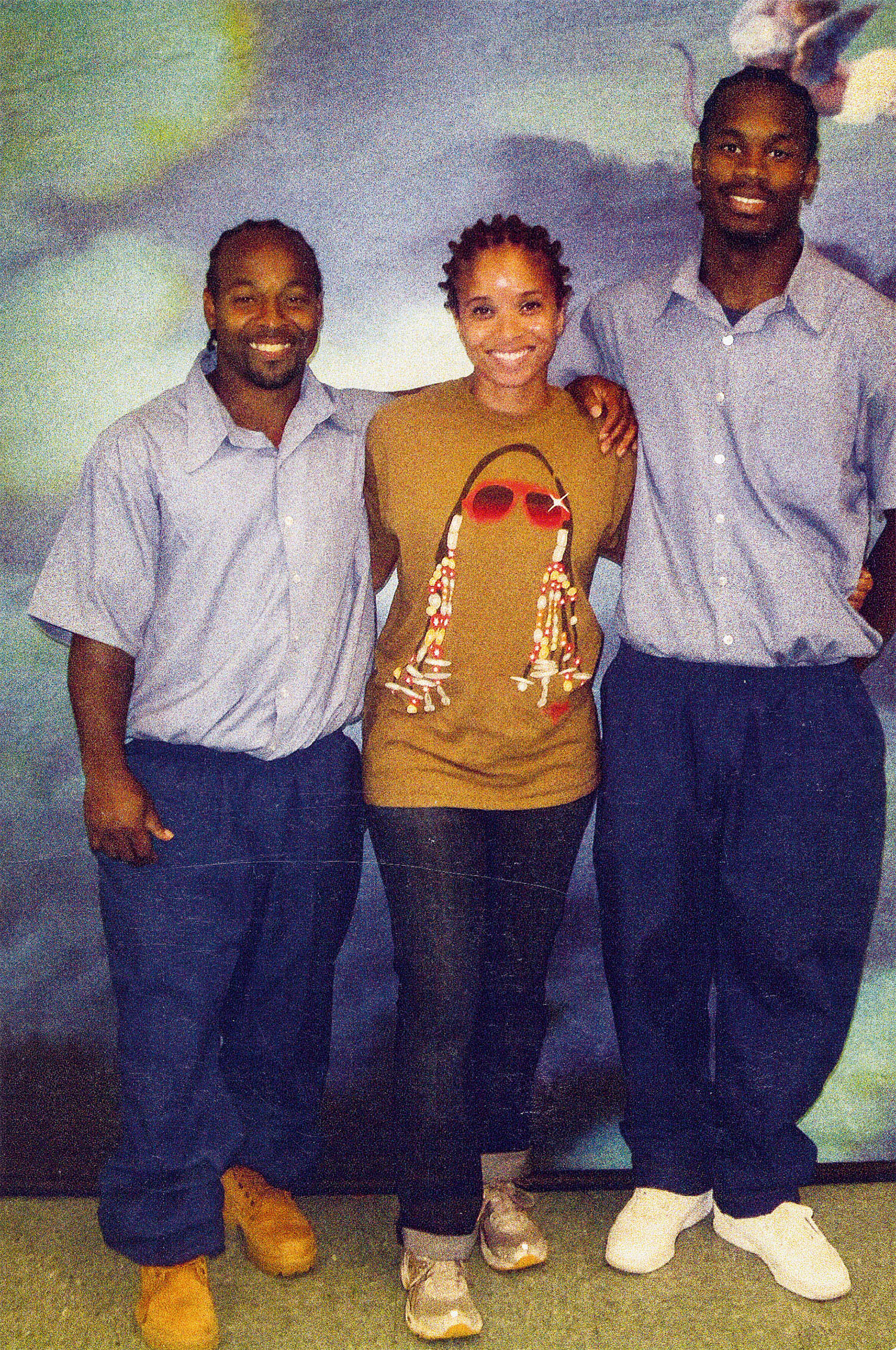

His requests for pictures make me think of other populations removed from their loved ones—migrant workers, those in exile or at war, those estranged from their families—who stay connected through letter writing and family photographs. I send him pictures, and he reciprocates. I have a small suitcase of memorabilia from Ohio prisons that includes letters, greeting cards, and prison photographs sent from Allen and other male relatives during their time incarcerated. The photographs are studio portraits taken by incarcerated photographers whose job in prison is to take pictures. Allen poses in them sometimes with props, always in uniform. The backdrops are painted by incarcerated people, and break up the uniformity and repetition of the prison attire and staged poses. There are also photographs from our visits to see Allen. In most of these, he stands in the center, and we huddle around, hugging him tightly.

In the first few years of his imprisonment, I could not look at these photographs that arrived tucked behind his letters. I dreaded opening an envelope from him if I could feel that the contents included something akin to the thickness and flexibility of photo- graphic paper. I would quickly glance and put the photographs back in the envelope, feeling much more comfortable with the letter. With his words, I had space to process and react. With the pictures, I had difficulty controlling my emotions. Gradually, my looks grew longer. I began to fixate on certain details—his hairstyle, a new tattoo, the shape of his arms and his neck. Then, as an experiment, I decided to hang the photographs around my home—secured by magnets on the refrigerator, tacked to a wall, or taped to the back of a door. After a while, they no longer unsettled me; they were just there, along with other images and possessions in my cluttered home.

Courtesy Nicole R. Fleetwood

In some ways, I forgot they were on display until a friend, who is an art historian, visited my home and inquired about one of them. Hanging on my refrigerator was a photograph of another cousin, also imprisoned in Ohio. In the portrait, De’Andre, in his late teens, smiles at the camera; he stands in a blue uniform, while hugging his grandmother (my aunt Frances). The backdrop is a painting of a winter scene, with snow-covered trees and rolling hills. A deer’s partial figure animates the landscape. I replied, “That’s my cousin De’Andre in prison during a visit from his grandmother—my aunt.” My friend was shocked: “Wow. That was taken in prison … There’s so much love in that image. They both look so happy.”

My friend had never seen a photograph documenting a family visit to an imprisoned relative and was unaware of how common these images are among groups most affected by mass incarceration—blacks, Latinos, Native Americans, and poor whites. The smiles and hug shared between grandson and grandmother were far from what he associated with prison life and culture. He compared the fantasy backdrops and setting to photographer James VanDerZee’s early twentieth-century portraits of black residents of Harlem. Also notable in VanDerZee’s work is the intentionality of his photographic subjects to use portraiture to document aspirations for upward mobility, equality, and inclusion. VanDerZee’s photographs have a sense of futurity, hopefulness, and often a subtle or explicit claim of the nation (the U.S. flag as prop or black soldiers in uniform); his images document anticipation of a better life for blacks of the time period.

My friend’s comments led me to see these photographs as more than documents of my family’s pain and loss, our separation from De’Andre, Allen, and other loved ones. Millions of them circulate between incarcerated people and their families and friends, given that there are over two million people incarcerated in the United States. In terms of sheer volume, prison photography is one of the largest practices of vernacular photography in the contemporary era. Like most vernacular photography, these images are primarily in private collections, housed in shoeboxes, photo- albums, drawers, and closets. These photographs serve as important visual and haptic objects of love and belonging structured through the U.S. prison regime, and provide an important counterpoint to a long history of visually indexing criminal profiles, such as mug shots and prison ID cards. Alternately, these photographs reveal the quotidian familiarity of penal settings for many millions who must navigate familial and intimate relations through prison bureaucracies and surveillance.

© the artist

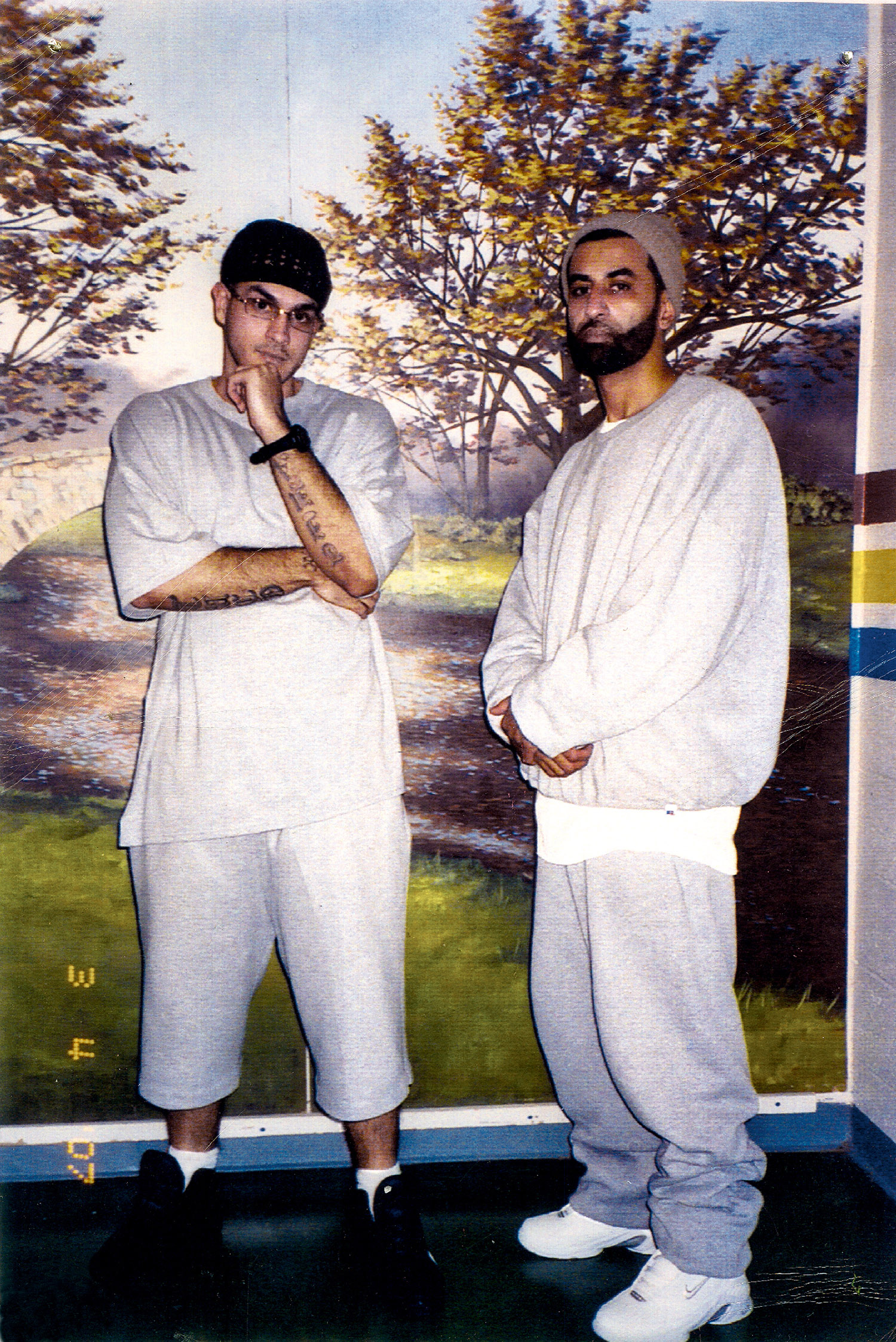

Among the most striking features that set these images apart from more publicly circulated photographs of prisoners are the emotive smiles, the imaginative backdrops, and the familial gazes of the photographic subjects that, one could argue, acknowledge their intended audience. Within portrait photography, backdrops tend to be read as signs of aspiration, futurity, and fantasy. In prison portraiture, the backdrops are more varied than the poses and uniforms of the imprisoned photographic subjects. Carceral backdrops project exterior life—a space outside prison walls—and they fall within landscape-painting traditions. While some backdrops reference iconic landmarks, like New York City’s skyline, the majority do not project a sense of place or specificity of location. Instead, they represent a sense of nonconfinement, a lack of bars, boundaries, borders—an ungoverned, yet manicured, space.

Until recently, vernacular prison portraits have had little visibility outside of their widespread interchange between incarcerated people and their personal networks. However, in the past few years, these images have circulated more broadly in public culture as art, appearing in exhibitions, catalogs, art auctions, and blogs dedicated to prison culture. David Adler’s collection of prison portraits, which has received considerable attention, is one example. Photographer Deana Lawson’s series Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jasmine & Family (2013) is another. The photographs are of Lawson’s cousin Jasmine; Jasmine’s incarcerated partner, Eric; and their young children. The name of the series is taken from the prison where Eric was incarcer- ated—a name that reiterates the dispossession and confinement of indigenous peoples, a carceral facility now primarily occupied by hyperincarcerated young black and Latino men from New York City, and staffed by rural white workers. In the series, we see the power of prison studio portraits to document familial and intimate relations. In some photographs, Jasmine and Eric hold each other affectionately. They kiss and hug. In others, they stand together as a family with their young children. The backdrop is unchanging and more austere than in many prison studios. It is a mural painted on cinder blocks; the lines of the blocks are visible through the paint. Against this backdrop, Jasmine and Eric—and other prisoners with their lovers, families, and friends—make memories shaped by the carceral system.

Courtesy David Adler

In one memorable visit, the emotional weight of this form of memory making comes to the fore. It was September 2012 and I was at Ross Correctional Institution with my cousin Eric. We were visiting De’Andre, his son and my cousin. Then twenty-three years old, De’Andre had been in an adult prison for more than six years and had six years left of his minimum sentencing. Eric was visibly uncomfortable. De’Andre had recently been transferred to Ross from another prison that was closer to home. He had written to both of us, depressed and worried about his safety. He had not had a visitor in over a year.

At Ross, the photography studio is right next to the guard’s desk and close to the visitors’ entrance. The backdrop is of an autumnal setting sun. The sky is a pale shade of pink, and centered at the top of the landscape is a large, warm yellow sun. The outer ring of sun bleeds into the pink and touches the edge of the lone tree on the horizon. The leafless tree stands majestic, peaking up above the sun’s rays. It’s one of the sparest backdrops I have seen, and its color scheme is unusual.

I speak briefly to the photographer while he sets up a shot; communication between the photographer and visitors is not officially allowed, but the guard does not seem to mind. The shift photographer, a middle-aged white man, tells me that he learned to take pictures in prison; he had never given photography much consideration when he was on the outside, he notes. The visiting room experience here feels more casual and less regulated than in most prisons I have visited, and yet this is one of the most restrictive institutions known to house prisoners who have committed serious felonies, or who have had disciplinary records at other penal institutions.

Courtesy Nicole R. Fleetwood

Photoshoots in prison tend to be quick and cursory. The photographer is careful not to spend much time talking with his subjects for fear of scrutiny by the guards, but today the shoots last longer, and those who are posing linger on the bench and chat with each other. Ahead of us, a young Latino couple spends considerable time, staging several images. The photographer walks to our table and tells us that we are next. De’Andre, Eric, and I take two pictures. In one, De’Andre is in the center, Eric is on his right side, and I am on the left. For the second picture, Eric says that De’Andre and I should take one together. De’Andre likes this idea; he has had very little contact with women in six years. He squeezes me much tighter than I expect when the photographer asks us if we are ready.

I have this photograph collection of Allen and De’Andre aging, maturing, changing in prison. The images of Allen, now almost twenty years into his life sentence, shift from an angry and scared teenager, to a depressed man in his twenties, to a resigned but hopeful man in his late thirties anticipating each time he goes before the parole board that he will be released.

After years of struggling with anger, shame, guilt, and depression about Allen’s life sentence at such a young age—his first time being arrested and convicted of any crime, but the judge having said during sentencing that he was making an example out of Allen so that other boys in our community would stay “in line”—his mother and sister work even harder to incorporate him into their daily lives. Allen is brought up with the frequency of one who shares a home with them. Their 2011 holiday card is evidence of this commitment. The photograph, staged in prison against an idyllic winter backdrop, is thickly layered as it circulates through many locations and emotional registers. Allen is the male central figure customary of family portraiture, as the women—his mother, sister, niece, and daughter—stand at his sides and lean in toward him. The prison portrait has been enfolded into another narrative and way of marking time—the holiday greeting card. The message on the card reads: “Have a blessed & prosperous 2011. Love, Sharon, Cassandra, Allen, Tanasha, & Mariah.”

Courtest Nicole R. Fleetwood

There is one image of Allen that unsettles me. He poses with his mother, my mother, and me during a visit in June 2009. My mother and I were in town to celebrate the graduation of four younger cousins from high school, a milestone that Allen did not accomplish. In this shot, we stand close to him. He hugs my mother and me tightly on each side of him. Aunt Sharon leans in, and we wrap our arms around each other. The women, all three of us, smile at the photographer. Our eyes are focused on the moment at hand, documenting our visit, a temporary break in Allen’s routine, a moment of connectedness. Allen’s eyes, his half smile, the creases around his mouth disturb me. His look is painful. It anticipates what will happen after we are finished posing and our visit ends. It will be another year before I see him. He will be here, living in a cell, when we return.

On February 2, 2015, Allen was released from an Ohio prison after serving almost twenty-one years. He walked out of the facility with his mother and sister accompanying him. They walked to the family car and took a group selfie. It was his first photograph outside of prison. In the weeks after his release, Allen used the smartphone that his mother purchased for him and took digital images of many of the photographs that his relatives had sent him over the past two decades. He then sent those photographs to us in text messages and emails with notes of love and playful emoticons. Many of the images that he returned were photographs that we had forgotten about. Allen had archived them. In many respects, he has become the keeper of our family’s photographic record. For the next five years, he will be heavily monitored through parole. Nevertheless, he told me to refer to him in this article’s conclusion as a “free man.”

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 230, “Prison Nation,” Spring 2018.