A Human Cartography of Collective Struggles

A Human Cartography of Collective Struggles

In his recent photobook, Martín Weber negotiates the past and the future in Latin America.

Martín Weber, El mejor./The best., Texas, 1992

© and courtesy the artist

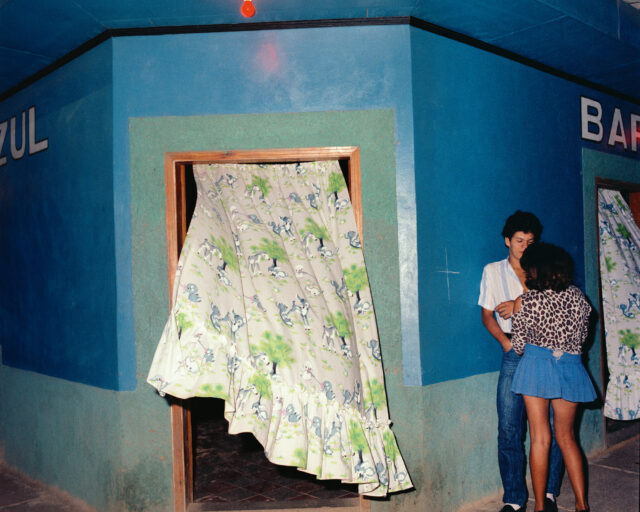

Map of Latin American Dreams by Argentinean photographer Martín Weber (Editorial RM and Ediciones Larivière, 2018) is the result of a long journey (1992–2013) through fifty-three towns and cities in Argentina, Cuba, Mexico, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Peru, Brazil, and Colombia. In the book are 110 monochrome portraits and several personal stories, like diary entries, that are interwoven in the narrative, which includes an essay by artist and educator Robert Blake. The gold color of the cover and silver in the negatives printed in the preface lead us to think about the symbolic space around material/mineral resources and the tragic history of their domination.

Martín Weber, Quiero ser policía./To be a policewoman., Maclovio Rojas, Mexico, 2000

© and courtesy the artist

At the beginning of the book, Weber points out in the travel notes: “Someone once told me that for someone born in exile, every trip is an exile.” And in the postscript: “Perhaps because my parents weren’t part of any armed resistance group against the dictatorships they suffered under, but were instead part of a conscientious opposition, it took me four decades to understand why I was born in Chile, and forty years to accept that I was born in exile.” These phrases, which resonate in the memory of our troubled Latin America, give sense to the images we observe, because the work is not only a question of giving a voice to those who have been denied this possibility, and visualizing the physical and spiritual marks and vestiges that conflicts and struggles have left in people, but also a question of why there are so many abuses, so many silences.

Martín Weber, Viajar a Italia para visitar a mi hija que vive allá./To travel to Italy to visit my daughter who lives there., Cachoeira, Brazil, 2005

© and courtesy the artist

Exile and forced displacement have been, for different reasons, a constant in the reality of our continent for decades, but it is also true that many, most, live or survive in their territories, dreaming that one day something can be transformed. The cyclical worldview of life, on which the belief systems of many indigenous peoples are based, fixes the possibility of the future only if one is aware of the present while looking toward the past. This can be an analogy of the tension between dreaming and living without forgetting—with memory.

Weber stages his photographs with patience and care. Individuals or groups are invited to pose holding a wooden board on which they have written their dreams in chalk—longings, fears, and promises, though almost always colored by violence, poverty, and daily life. This work invites us to build, from the unavoidable relationship between images and texts, a human cartography of common stories and collective struggles.

Martín Weber, Deseo vivir para mi esposa, mis hijos y mis nietos./To live for my wife, my children, and my grandchildren., Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008

© and courtesy the artist

This publication reiterates for us, both in the personal notes of the photographer and in his portraits, the failed policies and the fierce social inequality that invade us, while at the same time accounting for resistance and persistence. It proposes a reflection on time, both photographic time and history’s repetition of events, which seems more like a tragic song, as if dreams have been turned into supplications that are transmitted from generation to generation. The book is a sort of map between two times: the one of the archive and the one of the journey, of reality and dreams, photographs and texts, forgetfulness and memory.

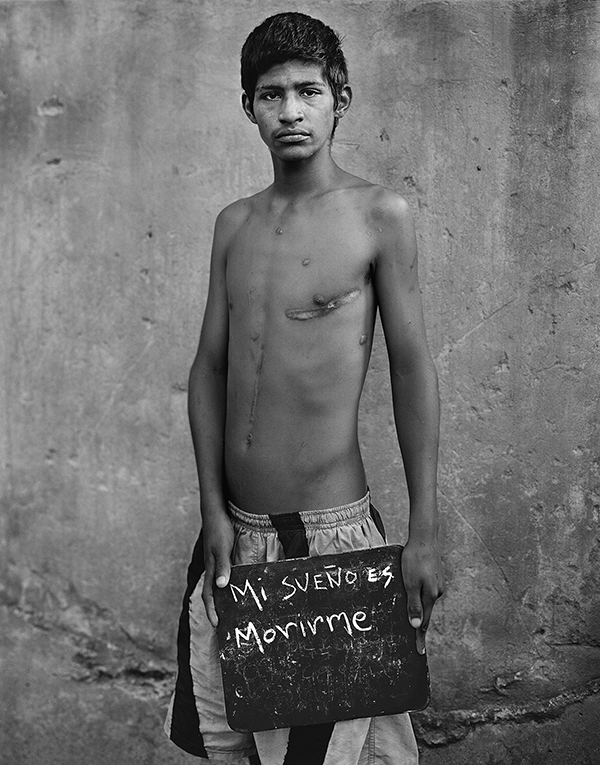

Martín Weber, Mi sueño es morirme./My dream is to die., Medellin, Colombia, 2007

© and courtesy the artist

In 2007, Weber photographed Cristián, the Colombian teenager whose portrait is printed on the cover of this book: “My dream is to die.” He poses with his scars, staring fixedly at the camera; his shot body was found six months later. It’s a tribute, perhaps; a second title, also. It seems that the dreams—of having health, work, land, education, the return of loved ones and the missing, having a decent life, affection—written by the women, men, children, and elderly portrayed by Weber, make us wake up and understand that, for all the differences that exist between cultures and countries, the dream of the majority of Latin Americans is to be able to live with dignity.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.