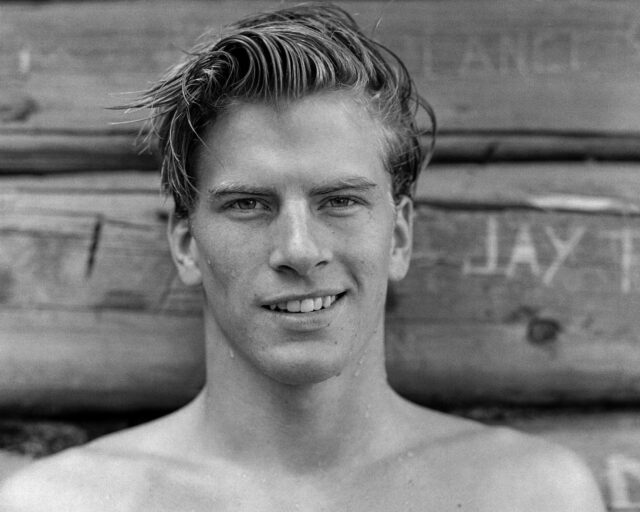

Matthew Leifheit, Adam, 2017

Fire Island, the legendary barrier isle that hangs precariously off the southern shore of New York’s Long Island, is a place where the past mingles with the present, where desires and bodies blur with the pounding surf. For his recent exhibition Fire Island Night, Matthew Leifheit walked for miles—the island has no cars or paved roads—to make his haunting compositions of men amid dark dunes. Or he stayed in, posing his subjects in repose in a clothes-optional Cherry Grove hotel. I recently spoke with Leifheit about the fantasies of Fire Island, unexpectedly living in a cottage where Peter Hujar and Paul Thek spent time in the 1970s, and preserving gay legacies against a shifting landscape.

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Will Matsuda: What led you to make Fire Island Night? Did it feel urgent?

Matthew Leifheit: Fire Island is a landscape in transition. It changes with the tides, and it’s changing with climate change. The island represents a gay history and a culture that is also in transition. Often, photographs that I love encapsulate the past and the present. I want these photos to do that as well.

My past work has always included historical materials because of my background; I’ve worked as a photo editor, which includes image research. While I was on the island, I started finding these pottery shards on the beach, which I’ve included in the show. I think about the work as a collection of fragments edited into a sequence.

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: Are you thinking about this as a documentary project? A fantasy? An escape?

Leifheit: I hope it’s all three. Guy Maddin, the Canadian filmmaker who did My Winnipeg, uses the word “docu-fantasia,” which I like. My friend Susan Howe calls it “factual telepathy,” which is an idea that archival facts from different points in time and place can talk to each other. I’m interested in the idea of poetic documentary. I think poetry is often a way to get closer to the truth.

Fire Island holds this cultural fantasy associated with gay culture. A friend, who recently transitioned to become a man, described a trip to the island as a “gay rite of passage.” It’s an escape because queer people can go there to express themselves when they can’t in straight society. But I’m interested in that idea now because more often people don’t have to go to geographical extremes to express their sexuality. Hopefully not in New York. So I’m asking, what is the role of this place? And how will it change?

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: And what is the role of these pictures in this cultural transition? Your photographs appear to be all of men, and I’m wondering how you frame this as our notions of gender and queerness are expanding?

Leifheit: I don’t want to speak for people, but yes, almost all the pictures in the show contain male-identified subjects. But I think I’m not necessarily making that look like a good thing, and hopefully that’s evident in the way I am looking at the place photographically. The series is also a dramatization of the world that exists there. I have exaggerated its homosocial qualities. Still, I hear it called an “only space,” which I take to mean an exclusive space where people of a particular marginalized group such as gays can be the vast majority rather than the minority, the rule instead of the exception. Historically for our community that kind of space has been essential, and in my opinion it still is. But now that people are having less use for gender boundaries, or would rather define their sexuality as queer, rather than gay or straight, what will the legacy be of this place that we are inheriting?

The artist Barbara Hammer recently established a grant for lesbian experimental filmmakers. I went to hear her give a talk and during the Q&A, I asked her about the purpose of a lesbian-only grant in a world where people are having less use for these kind of exclusive terms. She said something like, “There is a slippage now, absolutely, but in the slippage I don’t want a group of people to be lost. I want the tradition and the culture of being a woman-identified woman to continue in artwork as well as in history. It’s a different culture than a queer culture. It’s a different culture than a gay male culture . . .” She talked about specifically wanting to preserve a history of butch lesbians, and I appreciated that.

I think that a lot of the history that I’m talking about here, although not all of it, is a history of fags. It’s not necessarily queer by nature, because it has been an exclusive place. Fire Island is rumored to be this place only for muscle gays and advertising executives, but I think that was another time. Alongside the island’s history, I am trying to show the world that exists there now. There’s a wider range of people.

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: What drew you to Fire Island originally?

Leifheit: I first went to Fire Island in 2014 for a VICE story about underwear parties. Part of the reason I fell in love with it was that it represented this world that I didn’t really know existed. I had read about what it was like in the ’70s before the beginning of the AIDS pandemic. I was fascinated and excited to see that these parties with back rooms and wild group sex still existed. Since I first went there, PrEP [pre-exposure prophylaxis] has become much more widely used, which is amazing. It has also brought on a new permissiveness. People are willing to have riskier sex and more sex, as I perceive it. I think that is really exciting because the AIDS crisis silenced the voices of so many great minds, ending for many this era of extreme creativity, what seems to have been an amazing time where people finally had some sexual freedom. I think that with the rise in PrEP use, there’s been a revival of this hedonism on Fire Island. Maybe it never left.

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: I recently read a piece about the resurgence of Symbolism, a movement in the late nineteenth century where artists, poets, and writers were pushing back against Realism and responding to a chaotic world heading towards war as well as rapid technological acceleration. The work is otherworldly, moody, erotic, and it’s pretty morbid. It’s not hard to compare that historical moment with ours. Do you think Fire Island Night has any relation to this?

Leifheit: Oh, I like that. I do see these photographs as symbols that I’ve arranged into sentences of sorts. I believe that beautiful form has the potential to comfort people in times when it seems like the world makes no sense at all. The fact that the chaos of the world can be organized in a way that is beautiful and makes sense in a photograph can be very powerful, and it can give people hope. There are certainly other more direct ways of being an activist in your work, but I do believe that beauty is essential, and can be an escape. Earlier you used the word urgent, and I think that this is an urgent thing to show. At this particular moment, it’s of the utmost importance.

I had received a grant to research George Platt Lynes’s love letters and his scrapbooks leading up to World War II. The scrapbooks contain a lot of imagery that I’ve nearly re-created in some of these photographs. He posed for PaJaMa [Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret Hoening French] on Fire Island in these dark surrealist images. I don’t know if you would call it Symbolism, but Lynes was combining images of the male form with death on the battlefield and drownings. Photography is inherently mournful, we know. I do a lot of portraiture and I can’t help but think about the subject’s inevitable death.

I want to show how things wear away. Fire Island is almost a sandbar. It’s a barrier island that changes with the tides. I felt extremely exposed to the elements while I was there, living in a shack in the woods where Peter Hujar and Paul Thek used to go in the ’70s.

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: Wow . . . really?

Leifheit: My friend Marcell Yáñez, who wrote a thesis on Hujar’s circle, heard that there was this town in the middle of the dunes on the island where Thek and Hujar went in the ’70s. Susan Sontag, Vince Aletti, John Lennon, and Yoko Ono, too. It was this really remote place with artists and writers. It’s only maybe ten houses. Marcell had heard that Paul Thek had made lifecasts of his body on the island and had left pieces of himself around the town. Some neighbors had found a hand with a bunch of extra fingers. So we went looking for body parts there, and it turned out there was a house available for the summer. I spoke with the person who owned it, and their mother had rented to Hujar and Thek in the ’70s and liked the idea of an artist being there.

Weirdly, the cottage is right across from the death site of Margaret Fuller, who wrote America’s first major feminist work. It’s this low spot on the beach where things are always washing up. There was one point when a funeral wreath washed up right in front of me. There were also prayer balloons that came in from Long Island, I think. People had written the names of their loved ones on them and they drifted to this spot. History was really on the surface there.

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: How did living in that space affect this work?

Leifheit: Hujar is one of my favorite artists. Hujar waited until his subjects showed their truest form, whether they were a cow, a person, or a rock. It’s a process of waiting for a signal, of receiving. It’s the opposite of the way people think of Magnum photography. Until the commercialization of photography, photographs were not talked about as being “shot” or “taken.” All that photographic materials are capable of doing is receiving. In that way they are, like, inherently bottoms [laughs].

In preparation for a class I’m teaching at Yale, I read Kaja Silverman’s The Miracle of Analogy (2015), which is about the invention of photography. She quotes the part of Walter Benjamin’s Little History of Photography (1931) about long exposures in old portraits causing the subject to “focus his life in the moment rather than hurrying on past,” thereby capturing more of the sitter’s essence or aura or something. I’ve been working with longer exposures lately.

Peter Hujar worked in this way—its anti-aggressive. It’s empathic. I would like to be that way towards humans, but also towards the landscape. This is the first time I’ve ever photographed landscapes before, or even really been outside in this way. It’s amazing how you have to wait for the landscape. I had to wait for a supermoon for it to be bright enough for a photo. You have to wait for the mist to be in the air so that the light spreads in the right way. I also spent a lot of time trying to photograph that flash of blue light that happens after the sun goes down in the summer, just before darkness.

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: Taking a step back from this work, you recently graduated from Yale; you spent the summer on Fire Island, and now you’re showing this work in Brooklyn. What’s next?

Leifheit: Since graduating in 2017, I spent the last year teaching as an adjunct at four different schools, which was wild! It was too many classes to take on but I learned a lot. I spent a whole summer and probably the next six months making color studies. I photographed a million sunsets. When I graduated school I just needed something nice to do. I thought, maybe I’ll just do sunsets in Kodak Gold and it will be about, like, the death of analog or something. Eventually I woke up and realized I made a bunch of ombré gradients. It was so bad. You have to go through those phases, though.

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: You really do.

Leifheit: I just finished production on my first documentary, but it’s really more of an erotic docu-fantasy, like we were talking about earlier. It’s about George Platt Lynes’s love letters. And I just started a second film about a female impersonator who lost his voice on stage one night in 1982. It’s about the absence of his voice. I’m going to do a residency in Oaxaca this winter to start editing that documentary.

I’ve worked as a photojournalist and that’s so fast, but this video work has been slower. Film editing is exciting to me because I can just keep doing it forever. I’m going to continue working on these photographs of Fire Island this winter, as well. Eventually I want to publish them in a book, whenever it’s ready.

I’m just going to keep my work alive. I saw this TV interview with Harry Callahan from the ’80s where he said, “I felt that what I had to do was to live strongly, and to keep my photographs alive. As a result, I would have a lifetime of experience, from beginning to end.” That’s the only way I know how to proceed. I used to think I would die young but now I think I might outlive everyone, just lingering around and taking photographs while people and things slip away. I just want to make a masterpiece before I go.

Fire Island Night is on view at Deli Gallery, Brooklyn, through December 2, 2018.