In Mexico City, a Visual Archive of AIDS Activism

At the beginning of the exhibition The Seropositive Files, recently presented at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico City, is a provocative statement: “We are all seropositive.” As the curators Sol Henaro and Luis Matus note, “Having the virus in one’s blood or not does not determine one’s level of political commitment with the issue.” Today, even amid the COVID-19 crisis, the HIV/AIDS epidemic remains one of the world’s most serious public health challenges—and, as Henaro and Matus put it, “the construction of a collective memory” is as relevant as ever.

With all this in mind, Henaro and Matus have built an archive composed of materials of many sorts—photography, video, magazines, prevention campaign ads, and even a codex painted with blood—with the purpose of revisiting the recent past so that younger generations can access documentation of the emergence of HIV/AIDS, a time when AIDS was seen as an inevitably fatal disease, and artists and activists, seropositive or not, confronted both the fear of the virus and the vacuum of knowledge and medical treatment in extremely diverse and original ways.

Visualities and HIV in Mexico Collection, MUAC, Mexico City

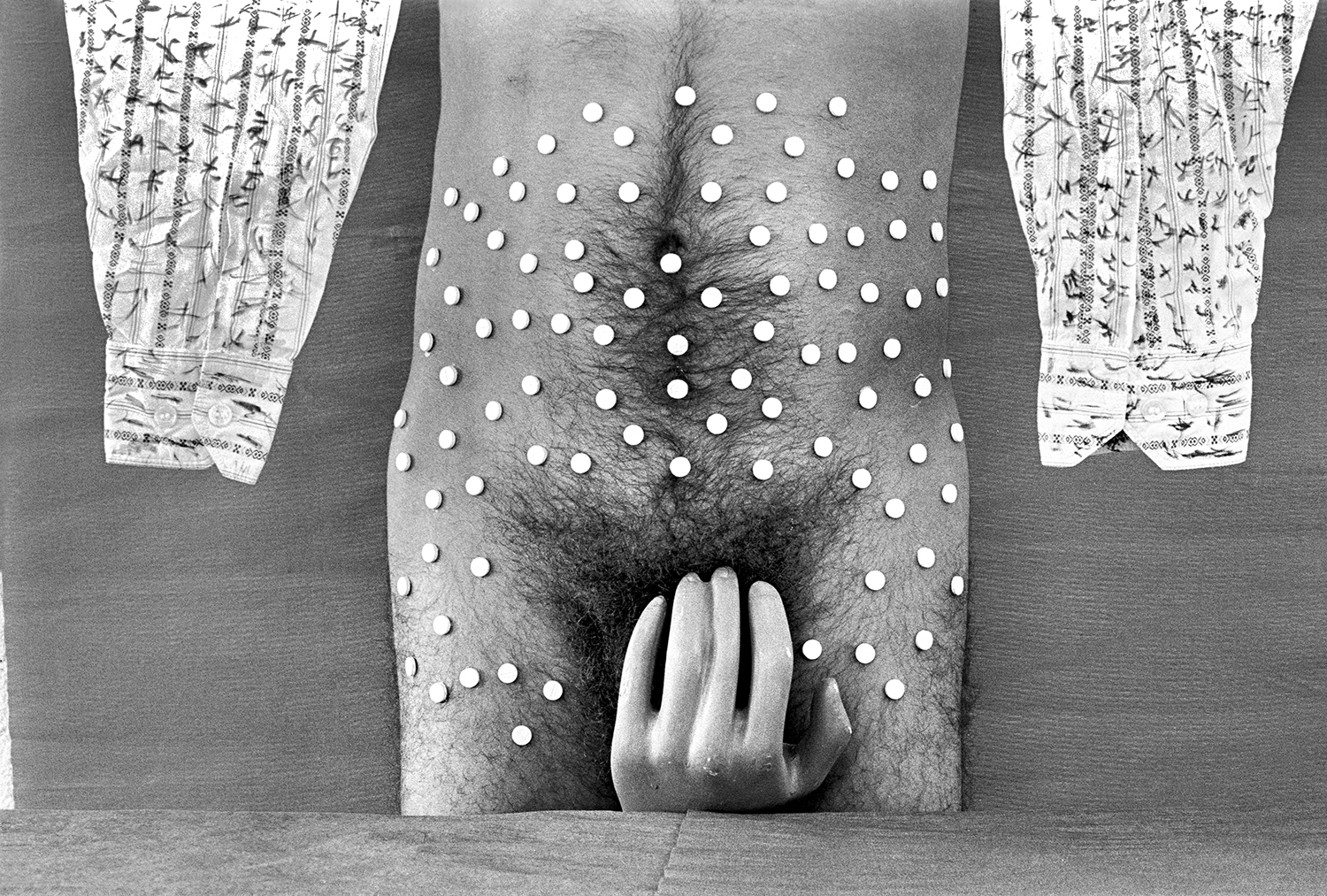

“Few diseases in the history of humanity have stirred the imaginations of individuals and societies to the extent of AIDS,” the gay activist Alejandro Brito points out. Photography, in particular, plays an important role: by being blunt, as in the image of Antonio Salazar embracing his dying partner; or playful, as in the Óscar Sánchez Gómez series where he portrays himself engulfed by all kinds of pills.

Earlier this year, Sol Henaro patiently walked me through the exhibition, explaining, in detail, every piece and every accompanying story.

Arkheia Documentatoin Center, MUAC, Mexico City

María Minera: Could you start by telling us how the Visualidades y VIH collection came about in Mexico, and what its purpose was?

Sol Henaro: When I first came to the Arkheia Documentation Center [at MUAC], I requested authorization to create an active documentation center. This meant we would not only search through the existing archives, but develop brand new documentary repositories. My initial interest was the creation of a collection on visuality and social mobilization in Mexico. Back then, I was mainly thinking of working on Ayotzinapa [the forty-three students forcibly abducted and disappeared in the Mexican state of Guerrero in 2014] and trying to bring together the visual remains of the movement that resulted from that event.

Along the way, the possibility of also creating a collection on HIV came up. This was partially due to a personal situation, as one of my closest friends, who is older than me, turned out to be HIV positive right in that moment; and he went through that situation as he would have in the 1980s—thinking that he would die, isolating himself from the world. This forced me to try to understand what HIV was and how I could support him by becoming informed about it. Then I realized that I had more acquaintances living with HIV than I had before.

Today, eight of my friends between the ages of 25 and 30 are living with HIV, and they faced the diagnosis in a very different way than my older friend, without the ghost of stigma and catastrophe. The situation has changed a lot since the development of antiretrovirals, PrEP [Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, a medical treatment taken on a daily basis by people who are at a high risk of HIV infection as a prevention measure], and other medical and pharmaceutical improvements that have allowed us to understand HIV as a chronic condition rather than as a death sentence.

I started to recall what was happening in the ’90s, the events we participated in back in the day, such as evenings for those who died from AIDS, concerts where condoms were given away, and prevention campaigns. Where did the visual dimension of all those events go? I thought we had to bring it back. And this is how the specific repository on HIV in Mexico was born, in the intent to rescue the visuals I remembered being made decades ago. At first, it was meant to be a documentary collection that would support research and memory, but in time, we added pieces with a rather artistic character.

Visualities and HIV in Mexico Collection, MUAC, Mexico City

Minera: AIDS representations from the 1980s and ’90s walk a thin line between art and social action. They function both as documents and images that shape the experience of living with the virus, making the condition visible. While the art and social functions are often indivisible, could you say more about how production worked back then as a way of keeping records or producing evidence of what Alejandro Brito defines in his catalogue text as the need to “politicize AIDS in order to achieve the scientific and technological advances that gave patients their dignity back”?

Henaro: Indeed. All these exercises of cultural activism are the ones that prompted the development of antiretrovirals, for instance. In Mexico, it is very clear that prevention campaigns have decreased, but also that the cultural community has stopped following the status of HIV, because the emergency has passed, at least for the media. Nowadays, it is rare to develop AIDS. You live with HIV, and that’s about it.

On the other hand—without this being a moral judgment whatsoever—emotional and sexual relationships have evolved to become extremely permeable, and the fear of AIDS that had been there for decades is gone. Many people have stopped using condoms, whereas twenty or thirty years ago, it was mandatory; also, hardly anyone gets tested anymore. Thus, we tend to forget that the virus is not gone yet.

Statistics are growing considerably. This is why we deemed it important to create this collection, to socialize this first research stage through an exhibition, a publication, and the development of public programs to bring the question of HIV to the public at a university museum, where most visitors are young. It also made sense to set visuality at the core of the project rather than focusing only on the artistic realm.

MUAC Collection, UNAM, Mexico City

Minera: Diseases and epidemics—plagues, such as cholera or smallpox—have always come accompanied by visuals and representations, but the appearance of AIDS introduced a variant: they were no longer just things made from the outside, with a sociological viewpoint, but much more intimate ones, situated in the body living with HIV. What kinds materials did you gather for the exhibition?

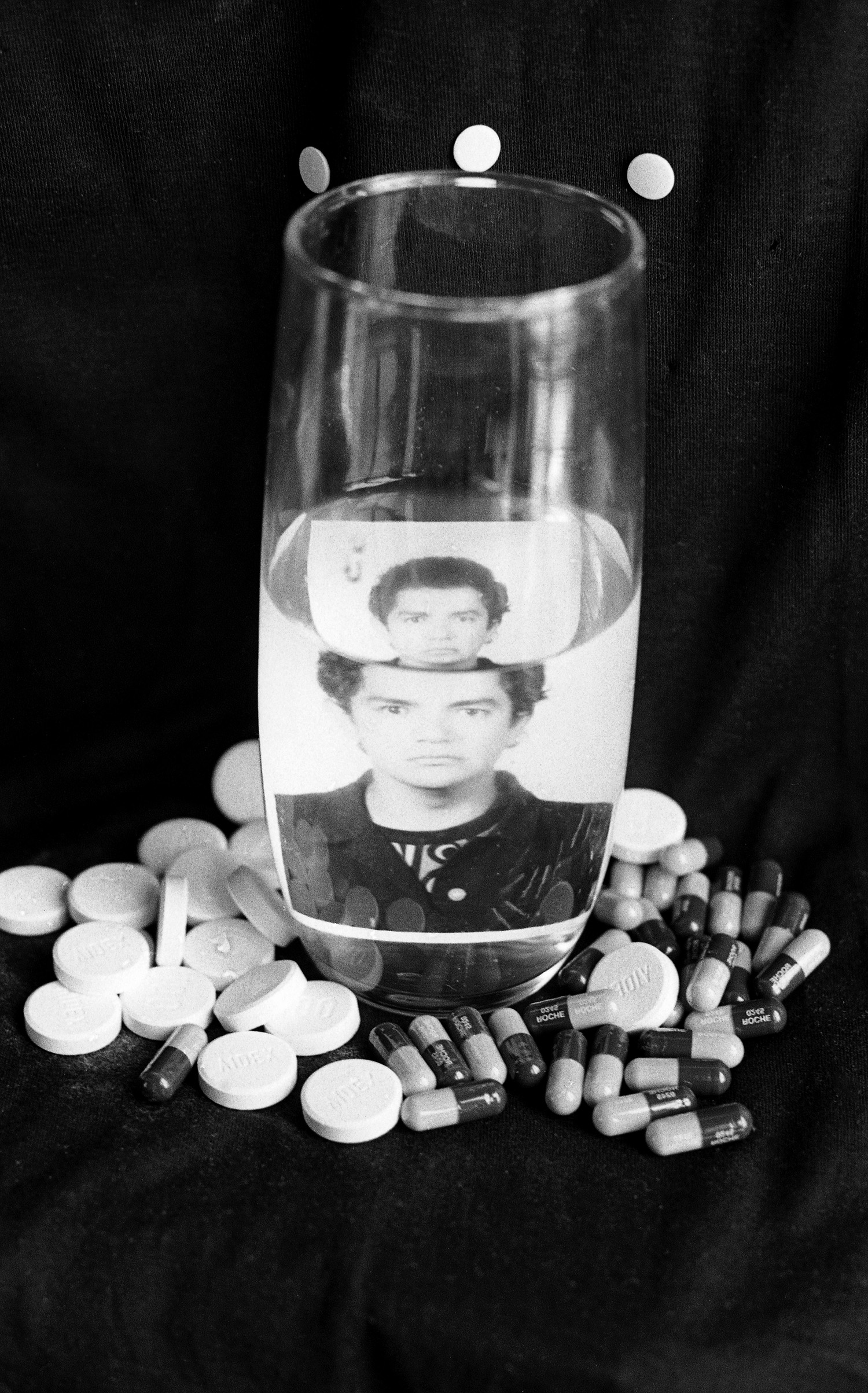

Henaro: We were interested in escaping the equation that our work would end up reinforcing stigma of a certain community. We had to find a way to escape male genital fixation, for example. We focused on looking for “accompaniment productions” [artistic works made by people not necessarily ill, but concerned], because you don’t have to be either homosexual or HIV positive to be able to make comments or declarations, or to develop affectionate, solidarity-based work. There are several works of this sort. But there are also others from people living with HIV, who turned the condition into their own production material. We can mention Óscar Sánchez Gómez, whose work has focused precisely on that: asserting his position in public and accepting his own condition at a time when he was still very stigmatized.

MUAC Collection, UNAM, Mexico City

Minera: Where do the materials come from?

Henaro: The exhibition is a review of everything we managed to gather during our research. Many materials are part of the documentary collection, whereas others come from the museum’s art collection, university collections, or other museums and galleries. Others are very specific loans from a variety of artists. And many of the things we managed to locate have now been donated to the museum.

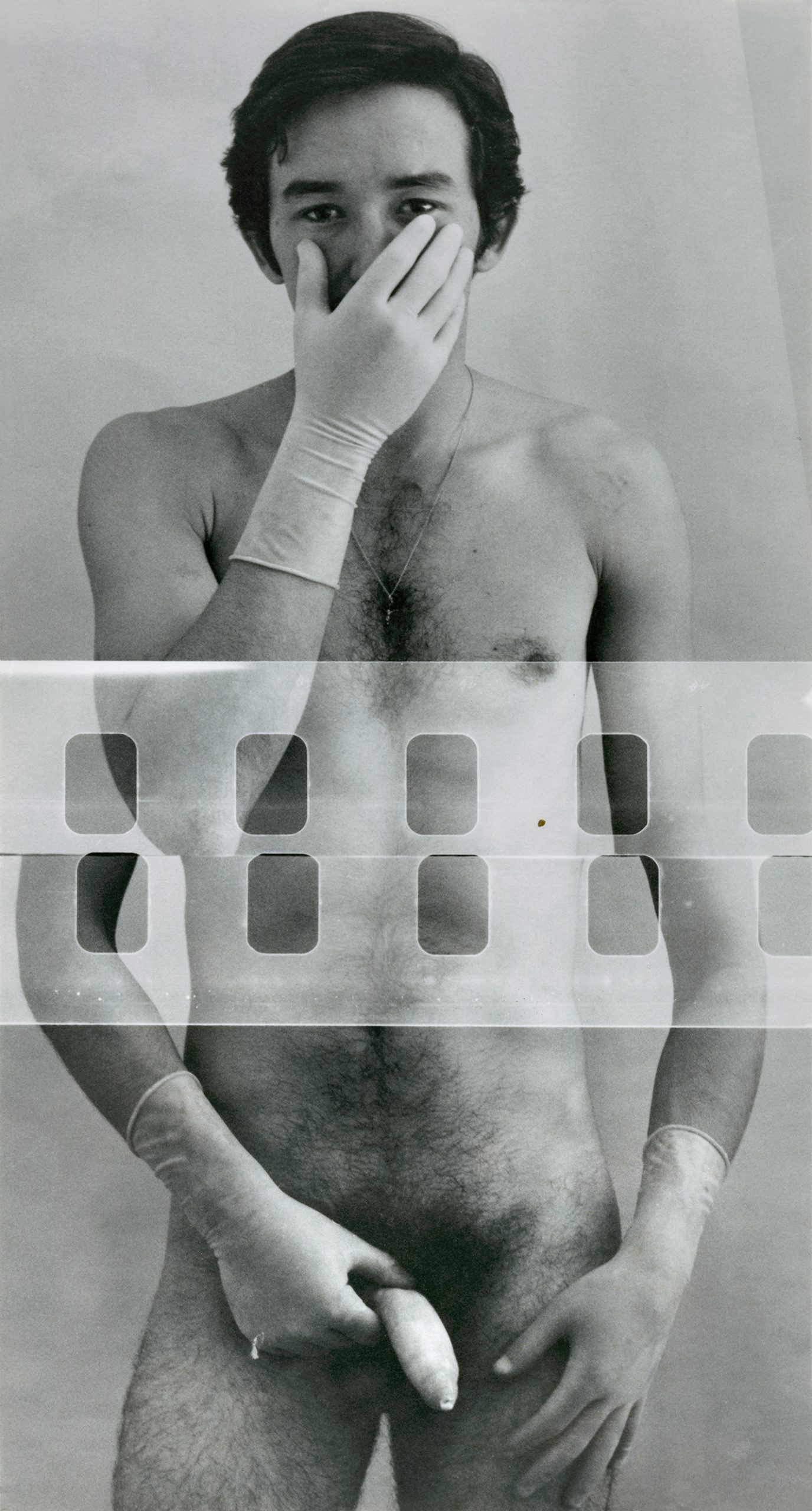

For example, the codex, Icnocuicatl Sidaids (Songs of Anguish to AIDS), from 1996, which was lent by Rolando de la Rosa. The first case of HIV in the world was reported in 1981, but the oldest material in the exhibition is the series El condón (The Condom) by Armando Cristeto, dating from 1978–79. We included this work because of how it managed to anticipate the issue of the asepsis of bodies, latex being the new interface. And although the first AIDS case in Mexico was registered in 1983, the emergence of cultural production was much greater in the ’90s. It seems like it took some time to understand the crisis, the fear; only then did most of the initiatives emerge.

Rolando de la Rosa was one of the most active artists at that time. He is neither homosexual nor HIV positive, but he did a series of works to disseminate the role of the condom through art, such as Un condón para México (A Condom for Mexico), the 1995 event that consisted of a series of choreographies and the installation of a ten-meter inflatable condom in the esplanade of the Palacio de Bellas Artes, as well as of a giant red ribbon, a gesture of solidarity with AIDS victims. This happened at a time when Provida [an antiabortion organization] was saying that the condom was a threat to life.

We went to see Rolando because of that event at Bellas Artes. He showed us the codex, which consists of thirteen parchment sheets, drawn with the artist’s own blood, addressing the movement of the virus between Mexico and the United States carried by migrants. It became something very interesting at that time. It combined elements of pop culture with pre-Hispanic iconography, which triggered discussions about all the genital possibilities of transmission, sharp objects, syringes.

MUAC Collection, UNAM, Mexico City

Minera: Is it possible to identify the period specificities and types of practices in terms of artistic proposals?

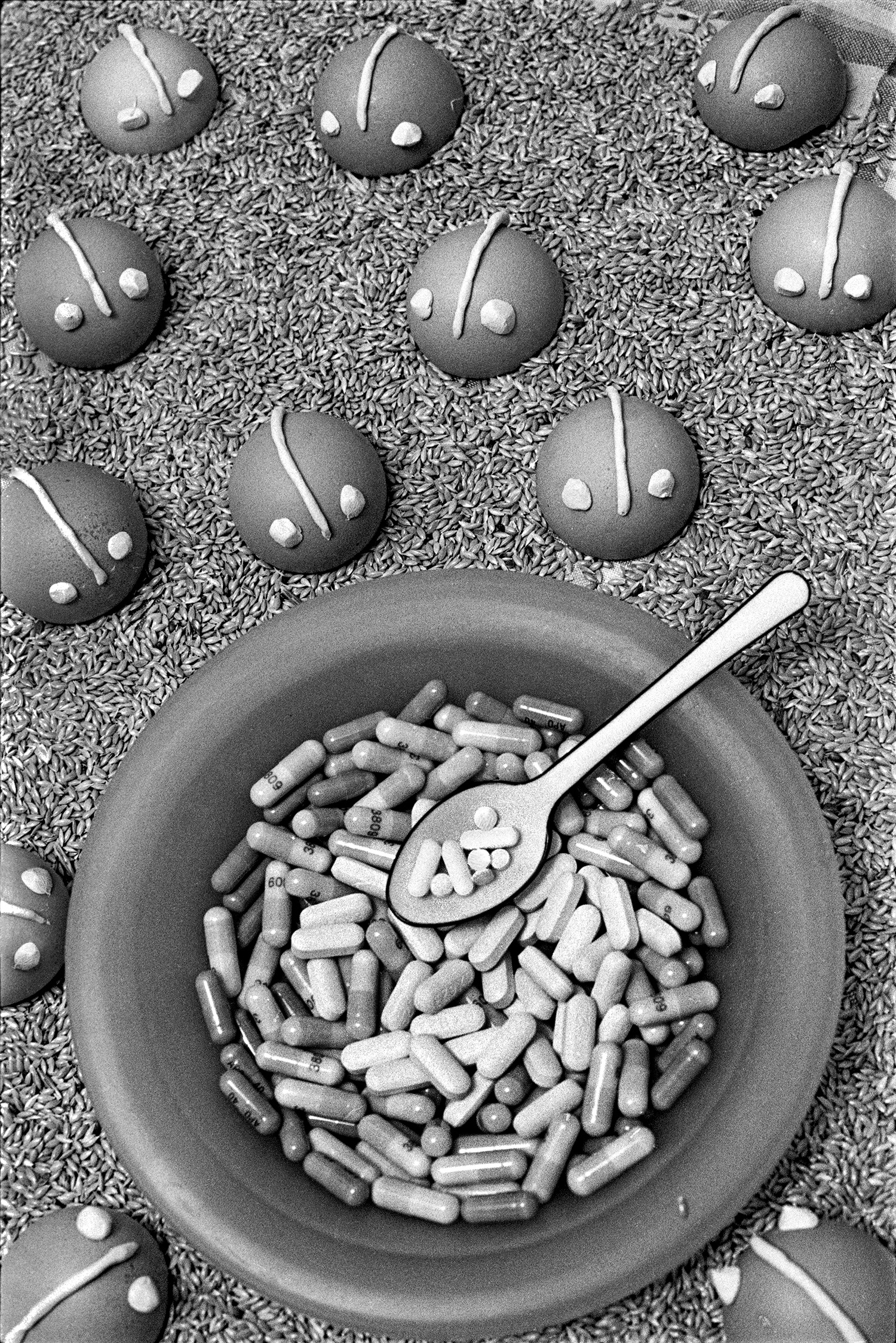

Henaro: Definitely. There are, for instance, many records of actions that were carried out at museums and festivals, and that were typical forms of expression in the ’90s. We can talk about the action of collective 19 Concreto [formed by Roberto de la Torre, Fernando de Alba, Lorena Orozco, Víctor Martínez, Ulises Mora, Luis Barbosa and Alejandro Sánchez], CD4, from 1995, in which two chess players carried a counter on their backs, showing global HIV transmission figures. We can also mention Richard Moszka, who stuck on a wall 4,800 pills that a person living with HIV has to take every year—Un año de pastillas (A Year in Pills), from 2001–2. What de la Rosa did at the Palace of Fine Arts was also an action, just like Roberto de la Torre’s 1996 Cinética moderna (Modern Kinetics), where he extracted blood from several volunteers and deposited it in test tubes that were placed on moving and crashing electric cars, aiming to show the random movement of bodies.

There are also examples of art objects, like the work of Hilda Campillo. Her Del buró de Blanca Nieves (From Snow White’s Bedside Table), from 1995, is a work that allows us to broaden our scope and talk about other perspectives on HIV. Using a drawer full of little condoms, Campillo suggests the infection risk Snow White would be exposed to in her relationships with the seven dwarfs—one we would nowadays classify as polyamorous.

Courtesy Salvador Irys

Minera: Do you think photography became these artists’ favorite tool due to the need to literally epitomize HIV in the body itself?

Henaro: We used Antonio Salazar’s photograph Jesús y el diablo (Jesus and the Devil, 1994), where he appears holding his partner, for whom he decides to engage in HIV/AIDS activism. Yet, this was the only image we decided to use showing these types of visibly ill bodies. While these bodies are those my generation remembers, we wanted to take a new direction and chose a different symbolic order, an affectionate and strong one which was not about—once again—pointing at stigma. We wanted our work to have a different visual dimension.

We include Omar Gámez’s series The Dark Book, from 2004, made out of images he took inside a dark room where he introduced a camera. We thought it was important not to focus only on these types of atmospheres; however, it was relevant to show a glimpse of them. This becomes especially relevant in the present, as we talk about “bugchasing” and “chemsex,” and these spaces—dark rooms, saunas—can be linked, although not exclusively, to HIV transmission. That’s why it was important to address them.

Gabriel Figueroa Flores’s photographs were important to include, as he was the photographic eye of many AIDS-prevention campaigns undertaken by the Mexican government. There is also a selection of Óscar Sánchez Gómez’s work, with pieces from his series Adherencia (Adherence, 2001–3), as well as Ajustada cárcel que me cubre (This cramped prison that covers me, 1997), that we deemed representative, and that are linked to medication and side effects.

Visualities and HIV in Mexico Collection, MUAC, Mexico City

Minera: By a strange coincidence of timing, The Seropositive Files happens to be presented as the world confronts the COVID-19 crisis. Once again, we are facing a pandemic. In this context, we are witnessing new forms of representing health issues, especially on social media. Do you see a resonance between the exhibition and what is happening today?

Henaro: The fact that we are living through this new global epidemiological crisis raises new questions and revives ghosts from the past. How does the response of government institutions, the economic warfare of pharmaceutical companies, the civil society response, and the possible emergence of new stigmas relating to COVID-19 compare to those related to HIV back in the early 1980s? I remember an urban legend back in the ’90s of having to be careful when sitting on cinema seats, because there might be pins with HIV+ blood. Today, an aseptic paranoia around objects and contact is emerging again. How long does a virus survive on a surface? Are we temporarily condemned to fear any contact or approach? In our exhibition, we include a piece by Hugo Corripio that reads, “AIDS is transmitted by fear”—a sentence that makes sense again amidst the current pandemic.

In “Chronicles of the Psycho-deflation,” a text that began to circulate recently on social media, the Italian thinker Franco “Bifo” Berardi alludes to the fact that “the effect of the virus lies in the relational palsy that the virus is spreading around.” The question that will concern us in the future is how will we restore and reconfigure our relationships to break through the relational paralysis that afflicts us today. It is indeed up to us—as it was during the HIV crisis—to imagine new ways of being and existing while we try to understand what we are going through.

The Seropositive Files: Visualizing HIV in Mexico opened on February 1, 2020, at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), Mexico City. Please see the museum’s website for updates during the coronavirus crisis. The bilingual exhibition catalogue is available for free download here.

This piece was translated from the Spanish by Enrique Pérez Rosiles.