Two Artists Interrogate the "White Gaze" of National Geographic

By Khairani Barokka

Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê from White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018)

Courtesy of at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books

In early 2018, National Geographic ran a piece entitled “For Decades, Our Coverage Was Racist. To Rise above Our Past, We Must Acknowledge This.” However, the magazine’s archival behemoth of denigrated bodies and minds still exists, imbuing its photographic subjects with racist notions that still need wider acknowledgment. The National Geographic archive is the cause of true harm on a mass scale, and dehumanizes, exploits, and perpetuates the worldview of our lands as resources for plunder, and our lives as classifiable, capturable, translatable only through the white gaze.

Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê from White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018)

Courtesy of at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books

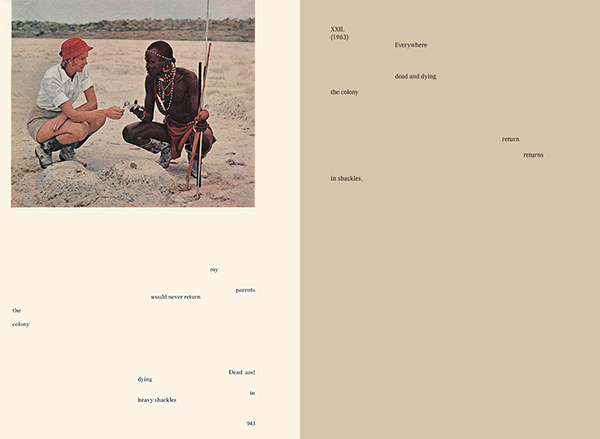

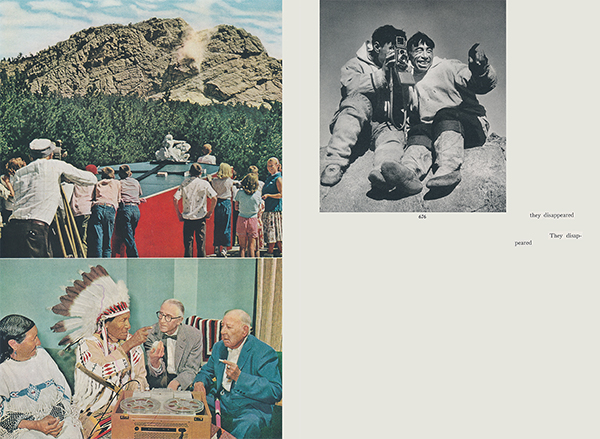

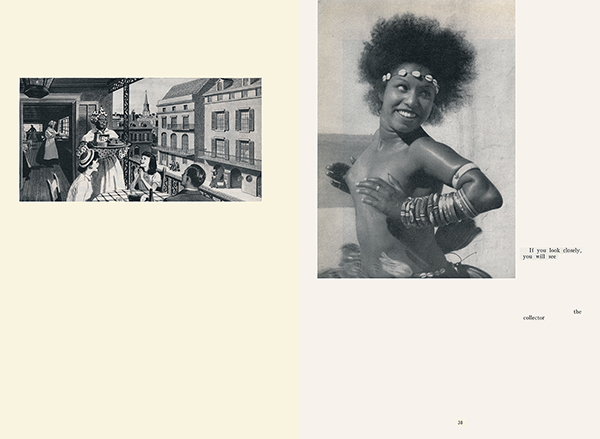

Artists and scholars Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê’s book White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018) is a work that exposes the National Geographic lens with razor-sharp textual acuity. The authors work harmoniously, with Dizon providing redacted pages chosen from the magazine’s issues and Lê juxtaposing them with original poetic text. Their cut-off point for mining the archives was the 1960s: Dizon explains that this is because a more neoliberal version of racism emerged in the 1970s, and in the 1980s text became embedded within the magazine’s images, which doesn’t fit White Gaze’s aesthetics of image-text interplay. Lê, meanwhile, contributes word choice and, crucially, visual spacing, to induce pauses and rhythm for the reader and sustain intended engagement with the photography. The size and positioning of the archival photos in relation to the poetry, timelines, and archival texts are always intentional; the results are deft, cutting. Captions note people “Scrubbed by their missionary guides until they shone” and a woman dancing bare-chested against “the / collector.” A transcribed letter from US President Eisenhower to Indian Prime Minister Nehru, encouraging peacemaking policies, lies opposite a large photograph of what appears to be a white man and woman driven by a South Asian man in a rickshaw—power dynamics persisting through the whiteness of gaze. The text at times excoriates the destructive processes of colonization, and at others adopts the language of the colonizer, or straddles the line between complicit and noncomplicit language. This brings up a slight tension in the act of absorbing the image-text interchange, requiring a subtlety of appraisal.

Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê from White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018)

Courtesy of at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books

In a discussion between Dizon and Lê that ends the book, it is noted that scholar Saidiya Hartman’s notion of “impossible stories” resonates in the dead’s inability to contribute their words to the conversation. I was struck by this impossibility, particularly in the image of the beautiful Polynesian woman captioned “She was destroyed by . . . US military operators.” Would the subject and her loved ones perceive this as a reinscription of violence? Is finding this out impossible, or could she or her family know she is being used in this book—and why or why not? The line between pointing out violent dehumanization in photos and reinstating that harm becomes blurry here; captioning children who could be our own ancestors with “little natives sing and play” is clearly a statement of the photo’s sinister subtext, but also a potential pain for those involved as subjects here, tangentially or otherwise. It is a credit to Dizon and Lê that this lack of power is addressed in their interview, but I found myself craving further discussion on how this affected their process and decisions.

Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê from White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018)

Courtesy of at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books

For these reasons, I found White Gaze most brilliant when a caption turns to the white gazer as at least partial photographic subject, in the sense of bodies or belongings in a frame; for example, “watch / the daughter of an American who buys rubber here for Goodyear.” A pristine mansion’s front yard exists opposite a page proclaiming “Slave labor”; a family gathering of Caucasians watching a film reel is paired with “Absence.” Also significant is the portrayal of resistance to white occupation, whether through the word “Struggle” captioning brown bodies under a colonizer’s flag, or photos 206 and 420 evoking “blacker / English,” language itself as battleground and weapon–textual as well as visual language. At its best, White Gaze illuminates the truth, palpitatingly urgent: “the camera may be a gun.”

Khairani Barokka is an Indonesian writer, artist, and poet. She has published two books, Indigenous Species (Tilted Axis Press, 2016) and Rope (Nine Arches Press, 2017), and her last exhibition as artist was Annah: Nomenclature at the ICA, London (2018).

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.