In This Film Series, Queer Sex Is Front and Center

From Andy Warhol to Marlon Riggs, MoMA presents film as a radical expression of sexuality and activism.

My Hustler, 1965. Directed by Andy Warhol

Courtesy Photofest

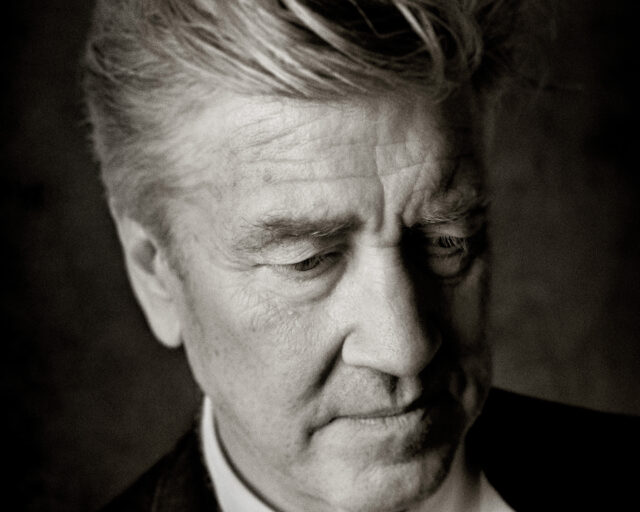

Near the end of Marlon Riggs’s incendiary 1989 video essay Tongues Untied, the poet Essex Hemphill trains his focus dead on the camera lens and delineates the difference AIDS has made: “Now we think as we fuck,” he says. “This nut might kill. This kiss could turn to stone.” In this moment, we see gay liberation metastasized into paranoid self-reflection. The might of the gay community becomes the might of its survival.

Riggs’s masterpiece originally aired on PBS’s POV series—much to the outrage of Pat Buchanan, who illegally lifted clips from it for an ad for his white supremacist 1992 presidential campaign. Ever since, Tongues Untied has left many people in awe. Among them is Carson Parish, the current theater manager at the Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Film, who used Hemphill’s words as the title for a film series that resurfaces an astonishing collection of the museum’s queer holdings. “Now We Think as We Fuck”: Queer Liberation to Activism moves from the early sexed-up fever dreams of Fred Halstead, through GMHC’s frisky, grief-stricken sex-ed videos at the start of the plague years; from Barbara Hammer’s charmingly new age 1975 Moon Goddess, to her almost unbearably beautiful investigation of the limits and aesthetics of hard science, 1990’s Sanctus; from the grit of 16 mm, to the “high art” legitimacy of 35 mm, to the democratization of the video camera.

I recently spoke with Parish about the line between art and porn, film defeatism, and why Hemphill’s words now sound less like an elegy and more like a siren.

Courtesy Photofest

Jesse Dorris: Let’s start at the beginning. Why this series now?

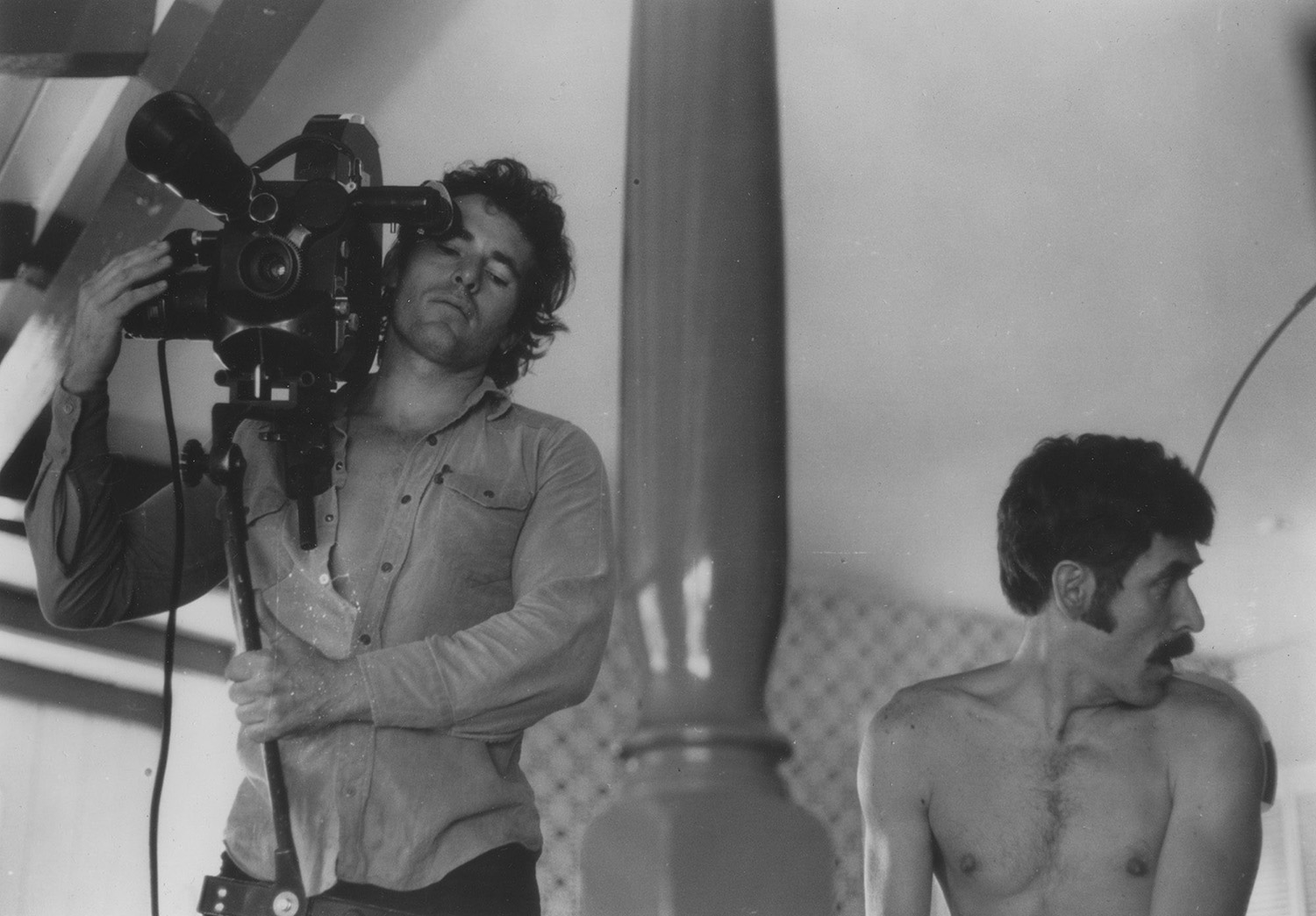

Carson Parish: A few years ago, the film department began an initiative offering people who weren’t curators the chance to work out programs. I reached out with an interest in queer history, and we began looking through what the collection had. Initially, highlights were some of the Fred Halstead films: L.A. Plays Itself (1972), The Sex Garage (1972), and Sextool (1975). They hadn’t been preserved, and desperately needed to be, so we brought them, and thanks to an amazing conservation collection specialist, Peter Williamson, we were able to get them preserved in time to show.

Dorris: How did MoMA come to have them?

Parish: I think it was Larry Kardish who initially formed the relationship with Fred. His work has been shown at MoMA, but it’s been many years. They were shown in the ’70s at least a few times, and there are people I know who were there in person and say the curators gave very long introductions to the audience, describing what they were about to see—particularly in regard to the fisting—to give them a chance to prepare themselves. (Those were very boisterous things to see at the museum in their day.) When his films were later released on home video and in theaters, Fred always made sure to note they were “now in the collection of MoMA.” He wanted that in there. And I think that fact really informed the vision of Sextool, which was designed to be a crossover between pornography and the art-house market. It wasn’t, sadly. It was a commercial failure, to say the least. But he shot it on 35 mm with the intent that it could be marketable to a larger audience than the 16 mm that porn houses used.

Courtesy Curtis Taylor and MoMA Film Archives

Dorris: A commercial failure, but I mean, what an outrageous artistic success.

Parish: Halstead’s films are remarkably ambitious. The cinematography is astonishing—I want to say in terms of porn films, but really in terms of anything. If you watch the first minute or two of Sextool, it’s immediately evident that you’re watching something that is critical both of pornography and of the art market. And of itself. And of cinema in general! It begins from a point of complexity that I think most porn films never even consider. The sex is graphic, of course. But L.A. Plays Itself has this strange, dream-logic narrative that mirrors a Maya Deren assemblage. It’s so bizarre that someone would think to structure a porn film this way. These films really do test the limits of consciousness, and they remain unique works on their own. There haven’t been a lot of copycats or reiterations.

Dorris: Why not?

Parish: If you’re making films classified as gay porn, that’s a niche audience, and it’s certainly scary to a lot of people to make work that excludes a large swath of the population just by its very nature. Fred never seemed concerned about that. He didn’t like alienating people, but he enjoyed making them a little tense in their seats. He enjoyed the idea that you would be sitting through something that would challenge you.

Courtesy The Estate of Warren Sonbert

Dorris: Speaking of challenging, let’s talk about Amphetamine (1966).

Parish: Warren Sonbert has a long history with the museum, thanks in large part to Jon Gartenberg, who did a lot of work getting his films preserved so we have access to them today. Amphetamine is one of my favorites, because it’s so hyper-specific in time. You can feel in it the shades of Warhol. Lou Reed percolating in the background. It’s such a quick shot of lightning.

Dorris: And just so, well, queer.

Parish: Even forty years ago, many of the people in the film department were queer. It’s been willing to test the borders, or the limits, of acceptability to an extent I didn’t realize. I knew about the Warhols and, say, Avery Willard’s 1967 Leather Narcissus, but I hadn’t realized how much the department invested in activism. The tapes we show later in the series are so tremendously important to queer history of the ’80s and ’90s. Some of the things we unearthed were a complete surprise to me.

Courtesy of Women Make Movies

Dorris: Like what?

Parish: GMHC’s Chance of a Lifetime is the most stunning thing. It’s a very early safer-sex education tape, released in 1985. Early sequences are somewhat silly, very much like a screwball comedy. And then there’s a sequence shot in the Mineshaft, that notorious leather bar. And then toward the end, we get this incredibly touching sequence on Fire Island that really does bring me to tears.

Dorris: Oh god, me too. It erases the difference between laughing and crying.

Parish: Seven of the main people who worked on it passed away within a few years of making it. It’s a humbling experience to watch, and I feel a lot of that weight of loss. And yet the first section is so silly; it’s closer to John Waters or even Bringing Up Baby (1938), and then the middle so closely resembles porn, and then the third sequence appeals to people dealing with HIV and learning to deal with partners who are dying. You have these different levels—having just seen something silly and then something pornographic—built up inside you. And then you’re pulled up into this world of loss. I hadn’t expected a safer-sex education tape to well up such deep emotion inside me.

Courtesy the filmmaker

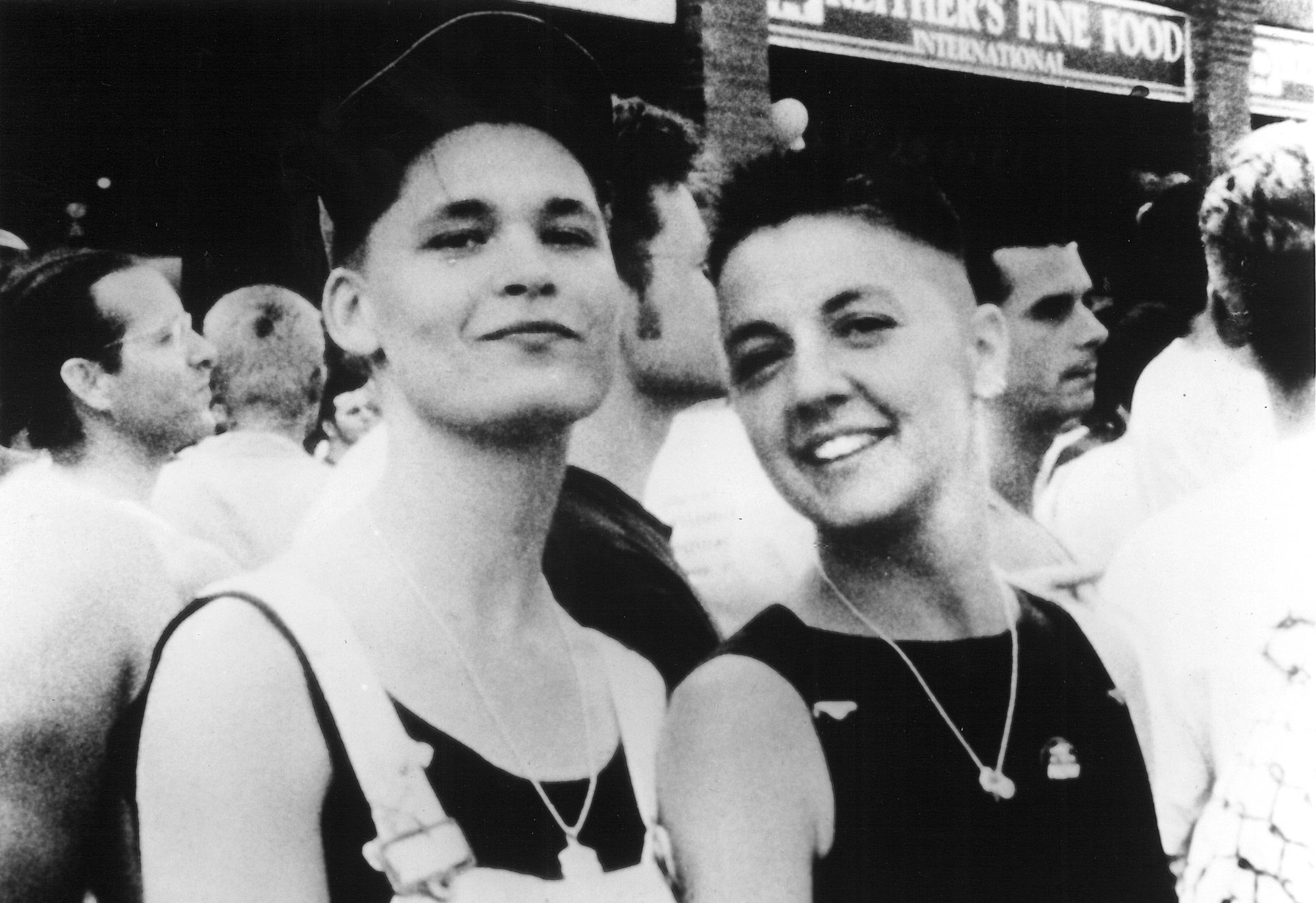

Dorris: It’s from 1985, that moment when it suddenly became much easier, technologically, to represent yourself—thanks to the relative accessibility of video—and increasingly culturally possible to represent yourself as queer. How do you see those moments intersecting?

Parish: The amazing thing is just how much the work transitions from gorgeously composed shots—even watching Halstead, it’s so clear many of his shots were carefully constructed—to literally throwing you on the front lines of protests. Even saying you’re on the front line doesn’t do it justice. You’re in the middle of it. Once you transition to video, where you can take the camera out with you, there’s a whole new world. If you look at Jean Carlomusto’s 1988 Doctors, Liars, and Women: AIDS Activists Say No to Cosmo, or Ellen Spiro’s 1990 DiAna’s Hair Ego, you’re seeing things never shown before in any sort of authorized form. It’s not even like down-the-street newsreel footage. This is in the middle of it. It might seem familiar to us now, with the prevalence of social media and cell phones, but at the time it was truly revolutionary.

Dorris: And it’s thrilling that it’s being digitally preserved.

Parish: Well, none of us is a film defeatist. We believe the original medium is just as critical as making sure it’s digitized. The two go hand in hand. Throughout history, when you forget, there are terrible consequences. So many of the artists in the ’80s and early ’90s knew the importance of documentation and making sure these images live on.

Dorris: Because they were seeing how quickly it could all vanish.

Parish: Yes.

Dorris: You’re showing Hammer’s work in tandem with Su Friedrich—two works each, made over fifteen years, sort of at the height and endpoint for 16 mm. What do you think that format allowed them to do?

Parish: Film is a degenerative medium in a different sense than video, particularly digital video. Like with Sanctus (1990), the film has such a fleeting, ephemeral texture. The prints are in great shape, but they’re worn, and those scratches are deeply entrenched in the DNA of this film, which is about loss. It mirrors archival practice. It’s about caring for the people and things you love, and how difficult that can be. So 16 mm is a perfect example of visual representation of what the film is also describing. There’s so much in the decision to stick to 16 mm and to allow all the things that will happen to the print to happen, as opposed to trying to control everything over time.

Courtesy the artist.

Dorris: Su Friedrich’s First Comes Love (1991) really blew my mind, a document from the marriage-equality movement made around the time Andrew Sullivan turned marriage into a conservative, assimilationist mechanism for taming.

Parish: What Su puts out is so radical. I just love the factuality of the film. It’s completely rooted in literal fact. It’s almost purely objective, which is why it makes such a clear and concise argument. In an overarching view of the world, there’s really been a miniscule amount of change in the thirty years since it came out. And that’s enraging to see, but the point of art is, again, to well up emotion. And then draw you into action.

Courtesy Milestone Films

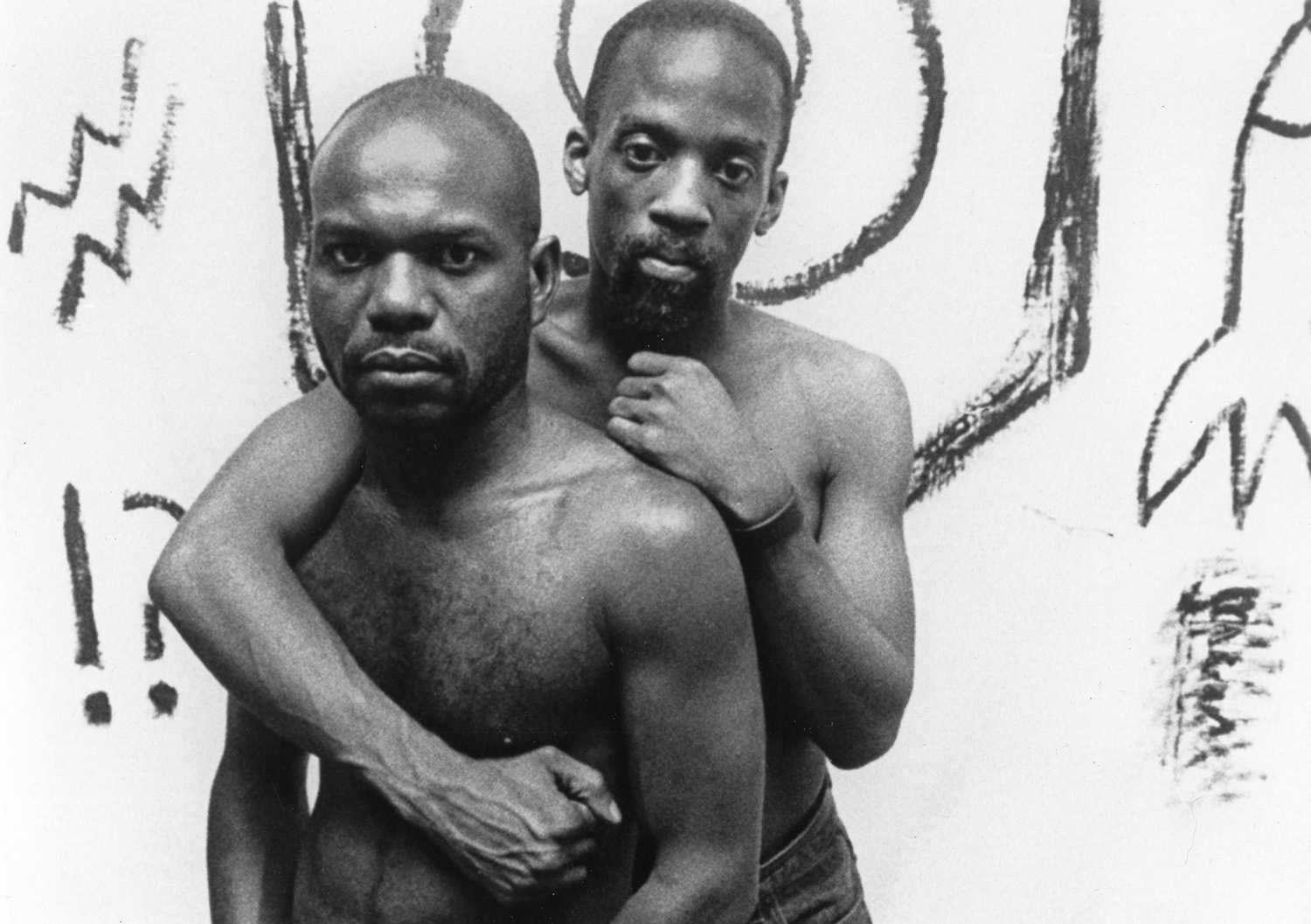

Dorris: Speaking of being drawn into action, there’s Shirley Clarke. Why did you choose to open the series with her 1967 Portrait of Jason?

Parish: It’s obviously a film about representation. And it’s so part of the conversation right now to talk about representation. You have a white woman who’s making a film about a Black hustler in 1967, and over the course of the film, she begins to seep into it more and more. As more alcohol is consumed, these lines between filmmaker and subject blur in really dangerous, scary, and exciting ways. There are so many possibilities of directions for this film to go, and yet somehow it goes in ones you never dreamed it could. And you’re peeling your wrists off the seats by the end.

Dorris: It’s like Alfred Hitchcock, but without the sets, the cinematography. The filmmaking even, sort of. Or like the best scenario of the Warhol idea of just turning a camera on and whatever happens, that’s the film.

Parish: And that’s what’s so brilliant about Clarke as a filmmaker. She had the restraint not to put everything in there. It would have been easy to edit in other ways, but she understood so well the idea that whatever happened is more interesting than what could have happened.

Courtesy Photofest

Dorris: The series concludes, chronologically, with Cheryl Dunye’s 1996 The Watermelon Woman, a great leap forward in terms of both representation and filmmaking. We still haven’t caught up with it. Why did you want to give her the last word?

Parish: If the series is divided into two halves, sexual liberation and then activism, The Watermelon Woman is an amalgamation of both. It’s tremendously sexy, and also critically about representation. It deals with such heavy subject matter as important and vital, and yet it lends such a broad appeal. I have to stop and remember it has fairly graphic sex scenes in it, because I think of it in some ways as a family film.

Dorris: Our chosen families, maybe.

Parish: By that I mean open and readily accepting of any audience that approaches it. I love the idea of closing with something that’s unifying across communities, to an extent. And which obviously had its own legal battle and horrible conservative smear campaign against it. But the film is so tremendously willing to disregard any sort of noise around it. It’s just speaking directly to you.

Courtesy First Run Features

Dorris: Which brings us to Essex Hemphill and his words as your title. To me, he always clarified this idea that suddenly gay men, unintentionally, shifted from lovers to killers. But also, kisses turning to stone like graves, like monuments.

Parish: In the first half of the series, artists are trying to break out and break free. In the second half, they’re trying to break in, into being seen as people and not violent perverse aggressors. To me, “Now we think as we fuck” reads: “Now we’re mobilized.” I think it’s a forward-speaking line. Vivian Kleiman of Signifyin’ Works really helped inform how I view the title and its role, and how meaningful those words were to Essex as well. They allow you to suddenly grasp these abstract concepts that have been percolating in your head for years and now are concrete in front of you. And also the gestures throughout the film, and the editing—it all forms something truly queer. It truly is a subversion of communication by way of something much more expressive.

Dorris: The editing in these films embodies queerness in how it embraces narratives but constantly interrupts them. It’s beguiling. And using those words for the title also keeps a little bit of filth front and center.

Parish: Absolutely. That’s part of the intention. And the other part is to force you to immediately confront loss, a loss that communities of color and people in lower economic strata are dealing with right now. It might be a historical line, but it’s not a historical expression. It’s present moment.

“Now We Think as We Fuck”: Queer Liberation to Activism continues at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through February 5, 2020.