Into the Museum

As one of the 2013 Darkroom residents at the Camera Club of New York, Pierre Le Hors’ solo exhibition, Period Act, presents a selection of work he produced using exclusively CCNY’s darkroom. The exhibition uses the museum as its point of departure; specifically, it interprets the viewing experience one has when walking amongst hundreds of vitrines and displays at a museum like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Through a series of black-and-white interior photos, still lifes, studio shots, and photograms, Le Hors’ photographs invite the viewer to follow him in his research, poetic tangents, and darkroom mastery.

Adam O’Reilly: Where did the title of the show, Period Act, originate?

Pierre Le Hors: The title initially came from a photo of a period room at the Brooklyn Museum—in the show it’s the one that looks a bit like a Vermeer painting. That photo was a jumping off point for me, and from there I became interested in thinking about the experience of walking through a museum. The American Wing photos in the show were taken at the Met, and to me that museum in particular is a place where time and geography seem to collapse. The longer one spends in such a vast place, the more the objects on display become formalized, and their historical specificity becomes secondary. Of course you can read the wall text and become engaged with each object—but overall, the experience I am interested in is about considering all of these objects from different cultures and eras on a level playing field. I mean not only the art objects themselves, but also the display structures that house them, and the architecture of the museum itself.

AO: The American Wing photos are a formal investigation of the space, there is almost this total disregard for the objects on display in their composition.

PLH: Even though they are photos of objects on display, they are not about the American nature of these objects, or even just about the objects themselves. It’s more about trying to resolve that entire space—the objects, the glass vitrines framing the central courtyard, the vitrines framing other vitrines, the light that comes through the side windows, the way it reflects and plays off all those surfaces. I wanted to find out how that entire space could be activated in the pictures, and broken down on a formal level.

AO: I find it easy to walk through the Met and not look at anything specifically, just enjoying the objects piecemeal; taking some things in, ignoring others. I take it this is similar to your own experience?

PLH: To me that is indicative of wandering around a museum, when things are no longer specific, and become more about display and arrangements. There is pleasure in that. However, I realize this is tied to my own position and experience, I don’t mean to say that is true of everyone who walks through there. People go to museums for many reasons, of course—to see something specific, or sometimes to just be surrounded by these cultural artifacts.

AO: Aside from being familiar with your work, my point of entry for this show was your press release for the show. The first paragraph is a reflection on the Met, and then in the next paragraph you refer specifically to a painting by Juan Dò, which in your show, you have a reproduction taped to the wall. Of all the paintings in the Met, why that one specifically?

PLH: When I started taking pictures at the Met, I noticed that painting in the background of one of my pictures. After sitting with that image for a while, I came back to the museum and actually looked at the painting in person. What is this painting? I was curious about it, so I found it on the Met’s website, in their catalog. It is a seventeenth-century Spanish painting, originally one of a suite of five paintings meant to depict the five senses, this one was the sense of sight [the Met only owns this one]. The girl in the painting is holding the mirror, and her other hand is up by her face, like she might be fixing her hair. It’s a strange pose. But the tension in the painting lies in her gaze, you can see her face in the mirror and she is looking off frame, to the right, at something we can’t see. This was interesting to me on multiple levels, first that this is a photographic device, this notion of “cropping” only existed only after photography. Secondly that the subject of the painting, ostensibly, is visual perception itself—in some way it seemed to focus the whole show around visual perception. I mean not only the black-and-white works, but also the color photograms which are given equal weight in the show. I don’t know if that comes through clearly, but I am ok with a little ambiguity, and leaving the viewer to bring the pieces together.

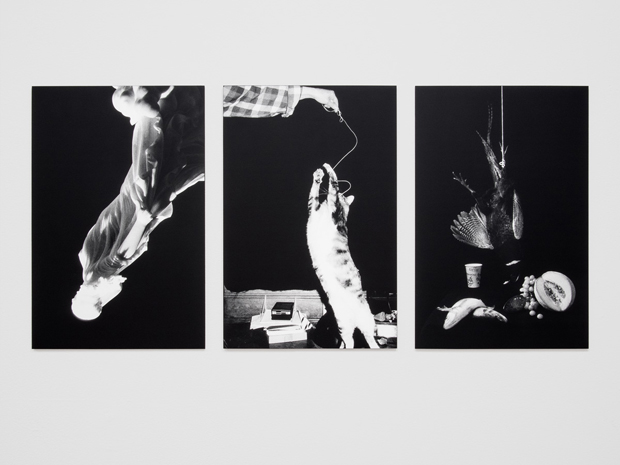

Pierre Le Hors, In Time, Nico Line, and Still Life with To Go Cup 2014. Courtesy the artist and The Camera Club of NY

AO: The other black-and-white photos in the exhibit look like studio shots, how do they fit together with the Juan Dò painting?

PLH: The studio photos play off various art-historical or photographic conventions, but they’re a little messed up: the cauliflower image relates to photography’s use in documenting natural forms, but also has this psychedelic quality. There is a very staged renaissance-type still life with an extra coffee cup, something someone might have left on the set by accident. The picture of the cat jumping is somewhere between a staged shot and a “decisive-moment” instant, while the photo of the sculpture seems at first to be a studio picture but is actually taken at the Brooklyn Museum.

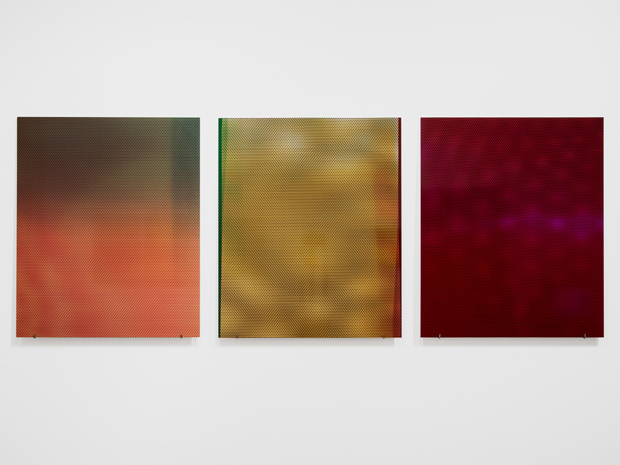

AO: The counterpoint in the show is the photograms that you made in the darkroom. Rather then giving the viewer’s eye something to rest on between the high contrast black-and-white photos, you’ve done the opposite.

PLH: I am interested in how the eye takes in those surfaces, what exactly they do visually, and how they push against the black-and-white photos, almost like noise or static. Your eye can’t fully rest on them, because there is no focal point and no depth, only surface and pattern. Each part of the image is allowed equal compositional weight, so the gaze is dispersed rather than focused, which enhances their flatness.

AO: In your artist statement on the CCNY website you write, “I want these images to speak to a certain loss of innocence for the young medium of photography, as it enters an age still grappling with notions of subjectivity and photographic truth.” I imagine you wrote that before you started the residency, but I was thinking about that statement while looking at the show where you approach a wide range of photographic styles.

PLH: This is not an original thought by any means, but we are in a phase where photography is both very self-reflective and self-reflexive. I think it’s easy to lose sight that photography is a young medium, it’s only been about 160 years if you want to trace it back the very beginning. And that feels like a long time to us, but it is an incredibly short time in relation to the span of pictorial representation. In photography’s infancy, the so-called “pictorialist” photographers were referring directly to painting, a system of representation they were familiar with. That early period seems so fertile with ideas and is still interesting territory to explore, but at the same time we are no longer so naive. Obviously, photography has totally diversified—it’s everywhere at once. I suppose I want to deal with photography’s role as a system among many others. But I don’t think we are at any end point, quite the contrary: we are only contributing to the medium’s language and long history.